Earlier in the summer D-M caught up with Catherine Riley whose new book The Virago Story: Assessing the Impact of a Feminist Publishing Phenomenon was published this year by Berghahn Books.

The Virago Story is the first full-length academic monograph about Virago. Our interview discusses the challenges of critically narrating the history of a company that has adapted to dramatic changes in feminism and the publishing industry.

D-M: How did you come to study Virago? Did the company have any personal significance to you?

CR: I was originally looking at Germaine Greer’s work as a possible PhD thesis, but during my MA study I became aware of this moment in second-wave feminism when women seized the means of production so I thought about doing something on feminist publishing. Virago was the obvious candidate because it was the biggest, the best known and was still going – and it still is.

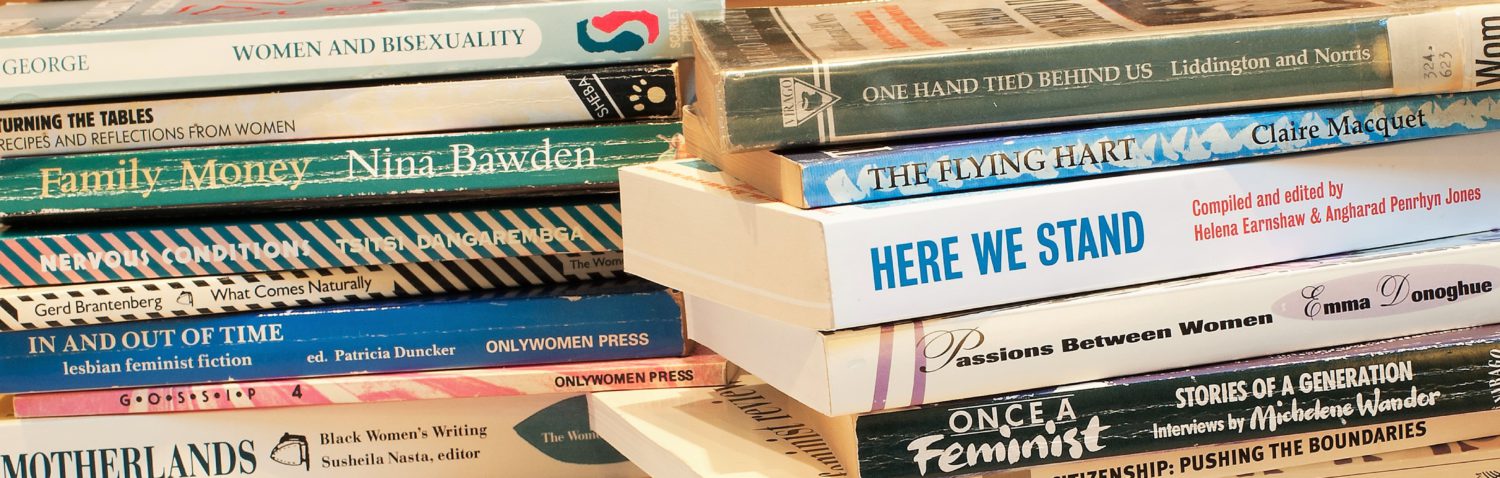

I didn’t really have any prior personal investment or interest in Virago – a Professor at Birkbeck, Hilary Fraser, introduced me to them. She was from that demographic of women who loved the books, and teaches English, and is interested in feminism, so is familiar with many, many of their books. As soon as I put feelers out about the press it became obvious that people were really passionate about it and readers really cared about the green spines on their bookshelves.

D-M: How did you approach studying Virago, what methods did you employ?

D-M: How did you approach studying Virago, what methods did you employ?

CR: I had a bit of luck to start off with. When I started my research I was working as a journalist and one of my editors, Paul Burden, knew Harriet Spicer and offered to connect us, which was very generous and, even more generously, Harriet accepted my plea for an interview. So I went to meet her at her house and we talked about Virago for a long time – I think she was sounding me out for the other Viragos, and she soon understood it wasn’t going to be a tabloid-style expose, so she then helped to connect me with Carmen Callil, Marsha Rowe and Lennie Goodings. Much later I interviewed Alexandra Pringle and Ursula Owen – so I was really happy I got to speak with all of them. I was also able to meet with authors like Sarah Waters and I tried to speak with Margaret Atwood, but to no avail. I realised, in the course of the research, that some of my favourite writers were Virago writers and I hadn’t made that connection. I was obsessed with Angela Carter, for example, after I read her in my first year at University – so it was a lovely opportunity really. In my thesis, there was a lot more literary analysis of texts published by Virago that didn’t fit into the book.

At the time there wasn’t any real body of research on feminist publishing. There was Simone Murray’s book Mixed Media: Feminist Presses and Publishing Politics and Gail Chester had written on this issue in the 1980s. To study Virago I had to learn about the business of publishing and how it works, including things like commissioning, contracts and advances. And how you can be published in hardback somewhere and paperback somewhere, and that’s really confusing in terms of someone like Margaret Atwood who, while being a staunch supporter of Virago, worked with different publishing houses simultaneously. So I approached the study from a mixture of disciplines – feminist theory, literature, business and marketing. It was also important to grasp, from the vantage point of the 2000s, how utterly soaked in privilege, tradition and sexism the publishing industry was.

My biggest challenge was the enormity of the topic. It crosses so many different research areas and at times it felt unbounded and I felt I could not grapple the breadth and depth of the material into something that was a meaningful narrative.

D-M: I think a huge strength of the book is how you seamlessly combine analyses of the business practices of Virago over a 40-year period – one defined by rapid transformations within feminism, capitalism and the publishing industry – with a scholarly revaluation of Virago’s contribution to the cultural landscape at large. Indeed, in your book I found it striking how you continually emphasise that Virago was a business, and that this has to be taken into account when we look at the kinds of books they published. Why do you think the business aspect of the Virago story need to be highlighted alongside, for example, a more common focus on genres and editorial approaches?

CR: It was something that naturally came out of the interviews with the women who worked for Virago. I think that the Virago women often felt the accusing finger of feminist groups who saw their methodology as necessarily patriarchal or in some way non-feminist because it adhered to capitalist principles, and they argued that there is not necessarily a corollary between the two – trade is not exclusively a male realm. I think it’s difficult from the perspective of now to understand how, in 1973, they were much freer to embark on something like a mass-market feminist publishing house. It would be much harder to do this now. Bloomsbury was founded with £1 million City backing, and the smaller feminist presses that have been founded recently have remained really niche or have failed because everything is conglomerated, or corporatized in different ways. The concept of the start-up now evokes Dragon’s Den, getting huge amounts of money to realise a winning idea, and actually it doesn’t smack of zines and do it yourself riot grrrl stuff which is the sentiment that Virago grew out of. It’s been massively criticised over the years for being middle class and you can see why, because of its taste, but the impetus behind it is utterly grassroots feminism and using the basic tool we have, which is telling stories, to create change.

D-M: I think the role of finance and the finance sector is a really interesting aspect of the Virago story. Many of Virago’s most significant investors from the 1970s-90s were men, or male-fronted companies, like Rothchilds Ventures Ltd. It really highlights the wider gender inequalities that surround business activities – i.e., who has access to start-up capital, and who can decide on what terms a business is set up, its objectives and values.

CR: It’s a power thing, isn’t it? If women are given power to trade, whatever the commodity – whether it is someone in a developing country setting up her own textile business so that she has access to her own money and can educate her children – these are the ways women take power, and Virago took power by setting themselves up in business, and in particular, in the business of books because books have a huge potential to create change because they educate and inform.

D-M: Your book is called The Virago Story. How is your critical engagement with the history of the press shaped by the corporate memory of Virago – the story the company presents and strategically uses in its marketing?

Of course Virago is a brand – and they are canny operators, and protectors of that brand. I was aware from speaking to Carmen that she was keen to have her version of Virago told and I imagine that the archives deposited in the British Library will be carefully selected. And of course we would all be like that if we created something so culturally and personally important. In terms my analysis of the story – which was tricky because of the much-publicised fall-outs between different people involved – it was to assess what happened based on multiple perspectives and tell a non-provocative version of that story.

D-M: What was your experience of meeting Carmen Callil? I’ve spent six-months reading her archives and find her a formidable and irascible yet irresistible figure.

CR: Well, bearing in mind I was a lot younger than I am now, I was quite daunted by her. She wasn’t trying to intimidate me, though, and was incredibly generous with her recollections; she showed me things that are probably now in the archive at the British Library, original papers and logos that I was very excited about. And we spent a long time talking, and I realised she was forming in her mind a way to tell her story. I had the impression she thought: this is my story, and I willing to set it out and tell it to whoever because it is a way of establishing my legacy, and establishing how I want it be told.

D-M: Yes it’s curious, isn’t it, because Carmen Callil really stopped being involved in the day-to-day running of Virago in 1982, when she became Managing Director of Chatto & Windus and the Hogarth Press, but she is so heavily associated with the company, even today. I wonder how possible it is, as scholars analysing companies and figures so invested – and, let’s face it, supremely talented in the art of storytelling – to offer different interpretations.

CR: I think that there is scope to offer alternative but also complementary versions of the story. For example, my book brings the story up to date – Virago is now 45 years old – and so Callil’s influence necessarily recedes in the later chapters of the book, and it is Lennie Goodings (current Chair) who comes to the fore. The history is there, certainly, but analysis of the books and the business of today provide a very different story. And that’s the point of my narrative – to show that Virago adapted to survive, adapted to thrive.

D-M: As the first person to do a large-scale critical study on Virago, your book is an attempt to organise the books Virago published into something we might call a coherent canon – a tradition – of women’s writing. In a sense you are mirroring Virago’s practices in the Classics series. I wondered if you had any thoughts on the responsibility of the feminist scholar to works produced by feminist publishers – what is our role in ensuring this work is not lost or forgotten and can, therefore, be re-valued?

CR: In pitching this book as a monograph, I said there is not a tradition of contextualising and describing the feminist publishing phenomenon that is a really important part of our recent literary history, and one that has so far been almost entirely un-examined, which is sexist. So recording these histories in a book is in a sense iterative of what Virago did in terms of getting books out and re-establishing them as part of the canon, or establishing them as part of the canon. Virago brought in new genres of writing, like feminist crime and sci-fi, and established them as part of the canon and I think it’s enormously important, as a scholar of literature, that the field of literature is diverse, and that we remember the work created by women. From academia to popular culture the stories that are remembered have always been the stories of men. Companies like Virago have done a really important job of staking out women’s space in an industry and literary culture where they haven’t, traditionally, been allowed to do that. So I hope that I am helping to affirm the work they have already done by surveying and documenting it in my book.

***

Catherine Riley is a feminist historian and writer, and an expert on contemporary feminist publishing in the UK. She has taught English Literature and Gender Studies at Lancaster and Northumbria Universities and Birkbeck College in London, where she completed her doctoral thesis on the feminist publisher Virago.

Catherine worked for two years as Head of Communications at the Women’s Equality Party, the UK’s first feminist political party, helping build it from the ground up before leaving at the conclusion of the 2017 general election.

Catherine now works in communications in the third sector, while continuing to write about trends in gender theory and praxis, particularly as it applies to publishing and social change. She is a member of the synth-pop band MX Tyrants.

Leave a Reply