A few weeks ago I received an email requesting an interview with me from two post-graduate students at Presidency University, Kolkata, Sohini Sengupta and Sourav Chattopadhyay, who convene Bhabuk Sabha (roughly translated to The Thinker’s Club). They wanted to engage with me on the University of Sussex archival memory of globally-renowned historian and founder of Subaltern Studies, Ranajit Guha, who was a lecturer at Sussex between 1962-1981. They had come across my work via references to my archival research in an obituary for Guha written by Vinita Damodaran, Professor of South Asian History at Sussex, which she wrote after Guha’s death in April this year, shortly before he would have turned one hundred years old. As Damodaran and others have noted, myself included, Guha’s passing went unacknowledged by the university leadership at Sussex until Damodaran’s obituary was released, yet his death was widely covered by educational and cultural institutions and media around the world. Despite this global attention, little is known about Guha’s two decades at Sussex. This was remedied at a Remembering Guha event I recently co-convened with Professor Gurminder Bhambra, Professor Vinita Damodaran, and Professor Ben Rogaly, colleagues in my new institutional home of Global Studies at Sussex. A joint publication on this event will be forthcoming in Discover Society.

Sohini Sengupta and Sourav Chattopadhyay convene an academic forum at Presidency University called Bhabuk Sabha (roughly translatable to ‘The Thinkers’ Club’) and are co-editing a publication that anthologises the proceedings of a December 2022 conference dedicated to the centenary of Ranajit Guha’s birth, along with some previously un-collected essays and letters by Guha, as well as contributions by scholars who discuss lesser-known aspects of Guha’s life and career. The resulting volume, which will be largely written in Bengali will be published later this autumn by Alochana Chakra. Their request for a written interview with me was to glean archival insights on Guha from his University of Sussex years, to help to shed critically reflective light on this formative period of his academic life. It also brought back memories from a chapter in my own research journey a decade ago, when I spent time in the libraries and archives of Kolkata during an AHRC international fellowship as a doctoral student, which you can read about here.

The images illustrating the interview below are taken from my presentation at the 20th October Remembering Guha event at Sussex.

Interview with Alice Corble on Ranajit Guha’s archival memory at Sussex

Interview taken on 26th October 2023 by Sohini Sengupta (Convenor, Bhabuk Sabha, Presidency University), to be translated and published in the Ranajit Guha Commemoration Volume by Alochana Chakra, edited by Sourav Chattopadhyay (forthcoming).

Question 1: Ranajit Guha joined the University of Sussex in 1962. For Guha, this was the first occasion of staying and working at a foreign university: an experience that, he later stated, expanded his view of the world and also made him aware of its various injustices (especially racism). How do the University of Sussex archives remember Prof. Guha? Could you tell us about the documents connected to Guha that you have found here?

The recorded memory of Guha in the Sussex’s institutional archive is very small. There are only two documents written by him in the archive, and one school pamphlet which lists him as a member of the AFRAS (Sussex School of African and Asian Studies) faculty. There are almost 700 archival boxes in the University of Sussex (UoS) Collection[1] so these two documents are like two little stars in a very large galaxy. In this sense, we might call this archival legacy an instance of what Guha himself dubbed a ‘small voice of history’[2], which is ironic given the power and legacy of his voice and the ways in which his work has impacted so many people across the world and shaped an entire field of Subaltern Studies scholarship and historiography.

Although archival traces of Guha’s time at Sussex in its institutional archive may be scant, the records that do exist speak volumes about both Guha as a teacher and about what we might now call a scholar-activist[3] (an identity I aspire to myself). Detailed below are the three documents I found.

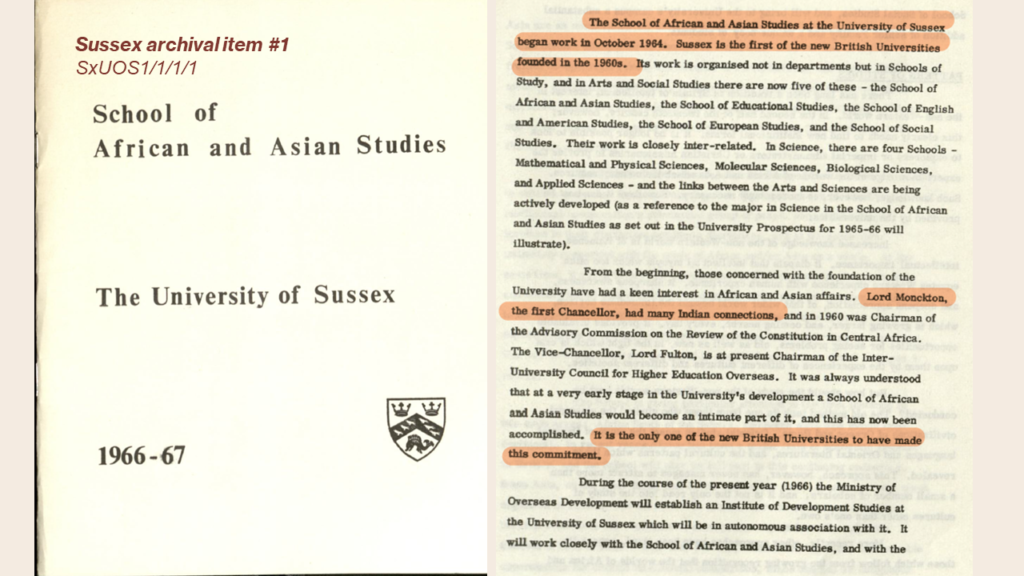

- UoS Archival item #1: School of African and Asian Studies annual report from 1966-67 which describes the ethos and development of the school which was established two years prior in 1964.

The University itself was founded in 1961, the first of Britain’s ‘new universities’, designed to “draw a new map of learning” [4] in the post-war, post-imperial era. The introduction to the AFRAS pamphlet states:

“From the beginning, those concerned with the foundations of the University have had a keen interest in African and Asian affairs. Lord Monckton, the first Chancellor, had many Indian connections, and in 1960 was Chairman of the Advisory Commission on the Review of the Constitution in Central Africa. The Vice-Chancellor, Lord Fulton, is at present Chairman of the Inter-University Council for Higher Education Overseas. It was always understood that at a very early stage in the University’s development a School of African and Asian Studies would become an intimate part of it, and this has now been accomplished. It is the only one of the new British Universities to have made this commitment.”

I have found no records in the University archives that document Guha’s appointment to Sussex in 1962, and the Alumni Office do not keep personnel records from this period. We know anecdotally that Guha was invited to take up the position at Sussex by Asa Briggs after meeting him during British Council visit to is in the late 1950s, when plans to establish Britan’s first new university were underway. As a founding father of Sussex (Professor of History, Pro Vice Chancellor and Dean of Social Studies) who coined its “new map of learning” vision to develop unprecedented interdisciplinary schools of study[5], Briggs was no doubt impressed by Guha’s deep intellect and unconventional approaches to social and cultural history. I wonder how his decision to employ the leftfield candidate of Guha, who was grounded in anti-imperialist and communist politics and had not yet completed a PhD nor published a book, was approved by the more conservative elite leaders of the university Lord Fulton and Lord Monckton. It is possible that there is a link here with the wider geopolitical context of national concerns about communist developments in the newly independent former colonies, which the then head of the British Civil Service Lord Bridges argued needed countering or containing by the new universities, in particular Sussex[6].

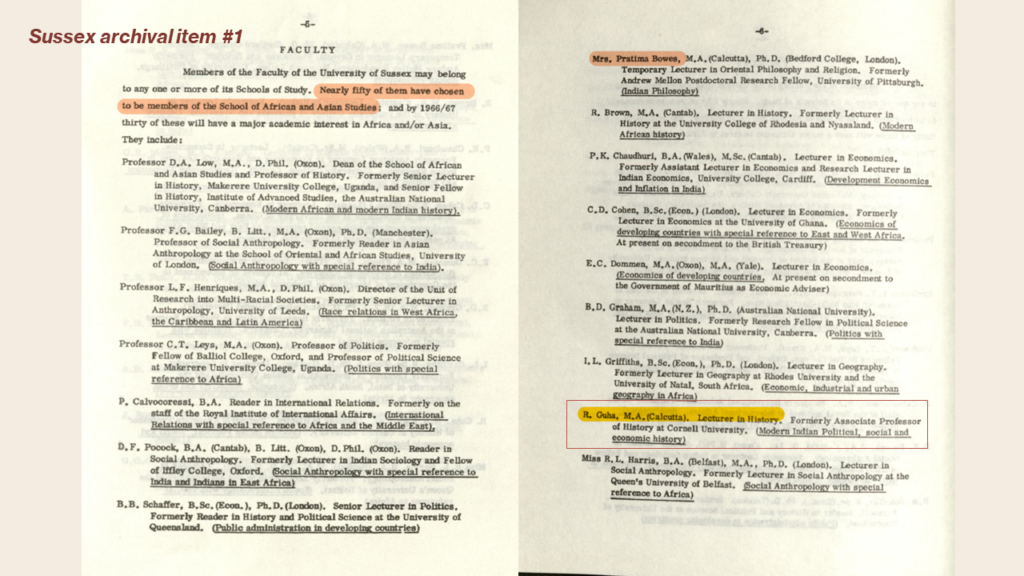

The full faculty list of AFRAS in 1966 is included in the AFRAS pamphlet, and Guha is listed on page 6 as follows:

R. Guha, M.A. (Calcutta). Lecturer in History. Formerly Associate Professor of History at Cornell University. (Modern Indian political, social and economic history.)

I had not realised before reading this entry that Guha had undertaken this visiting professorship at Cornell, and discovered via the Cornell University Center for International Studies Second Annual Report (available online) he was Acting Associate Professor of History at their Center for International Studies, which demonstrates how far his global reach and interests stretched during this formative time in his career. As far the archival records and conversations with Sussex scholars who knew him indicate, Guha was never promoted beyond the entry level role of Lecturer during his time at this university.

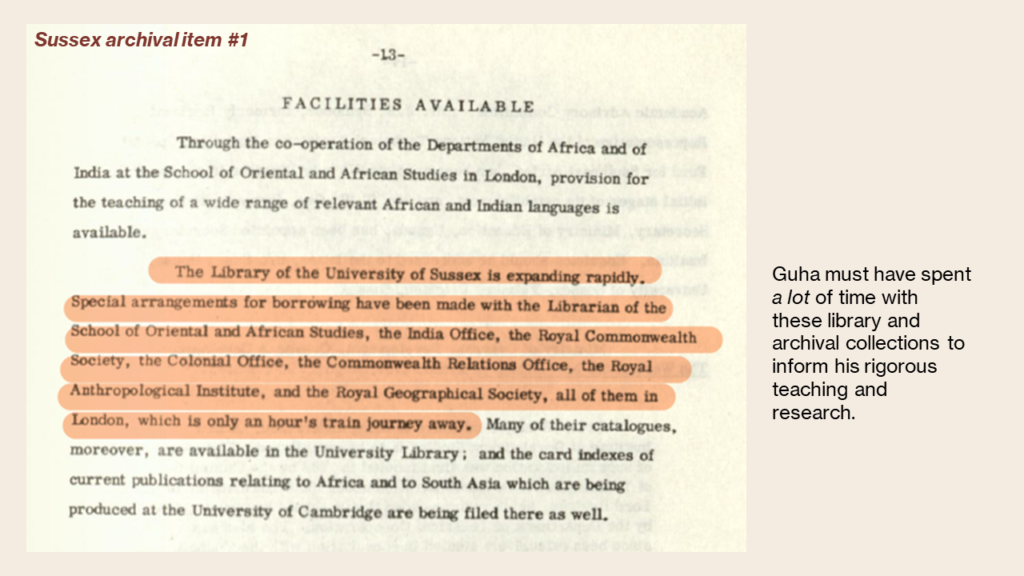

Guha is not mentioned elsewhere in the 1966 AFRAS pamphlet but one detail on page 13 that stood out to me whilst reflecting on his time there is the section headed ‘Facilities Available’ which lists the Library and archival resources available to faculty and students in the school, through inter-institutional cooperative relationships between Sussex and “the Librarian of the School of Oriental and African Studies, the India Office, the Commonwealth Relations Office, the Royal Anthropological Institute, and the Royal Geographical Society, all of them in London, which is only an hour’s train journey away. Many of the catalogues, moreover, are available in the University Library.” I can imagine Guha must have spent a considerable amount of time with these catalogues and collections to research the vast bodies of knowledge he imbibed to feed into his teaching and research.

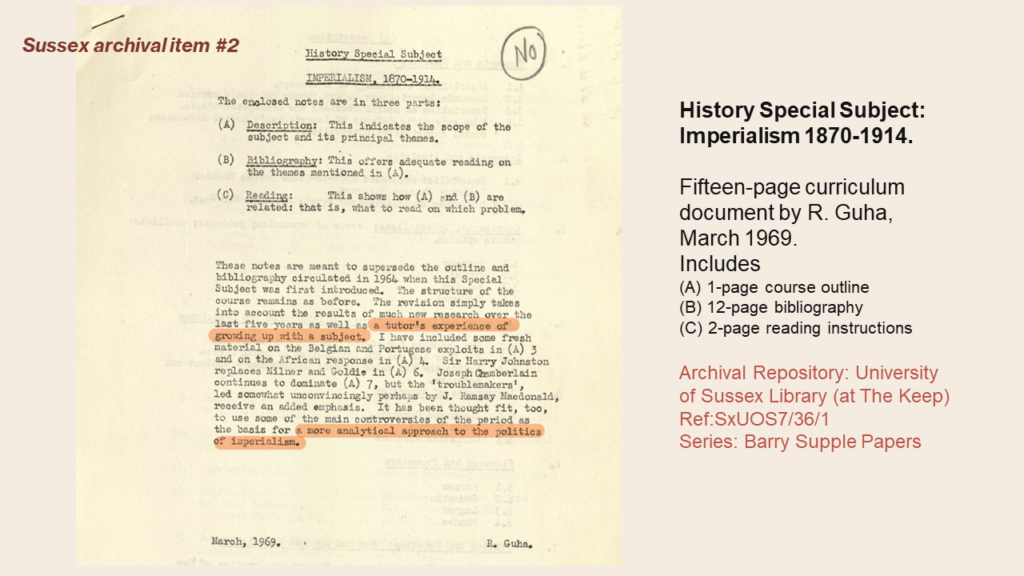

- UoS Archival item #2: copy of a syllabus of one of Guha’s teaching modules, titled ‘History Special Subject: IMPERIALISM, 1879-1914.

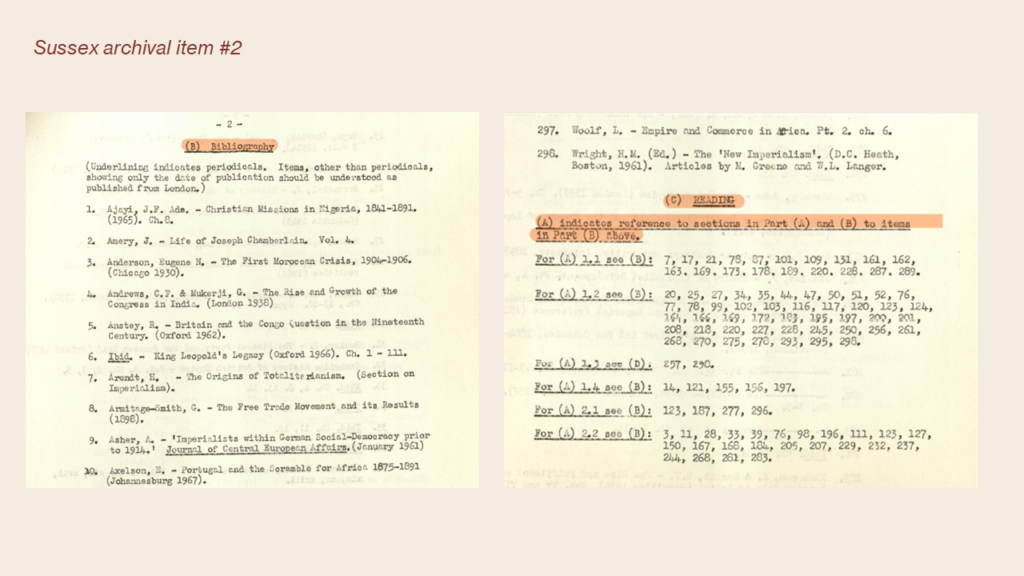

This fifteen-page typescript document is signed R. Guha and dated March 1969. It is divided into three parts:

(A) a one-page course outline split into the following eight weekly subject areas: Concepts and theories; Interests and Rivalries; Continental Imperialisms; Expansion and Consolidation: Collaboration and Resistance; Instruments of Expansion; Pioneers and Promoters; Parties and Politics: For and Against Imperialism; Propagation of the Imperial Idea. Each of these sections have numbered subsections that detail the countries, figures and projects that detail each of these subject areas.

(B) A twelve-page bibliography which totals 298 references spanning an incredibly diverse range of cross-disciplinary sources.

(C)A two-page alpha-numerical instructional list to guide students in how to match the extensive bibliography to the sections and subsections of the curriculum topic outline.

As Rudrangshu Mukherjee reflects, “Guha taught his students and his readers to read texts against their grain to gouge out answers that were not apparently visible.”[7] Sussex humanities undergraduate degree programmes still today include a ‘special subject’ module in the third year, but having worked in the Library reading list team over the past few years, I can assure you that there are no reading lists anywhere near as extensive and complex as this! Students of Guha’s must have had to dedicate a lot of time to succeed in this course, which I imagine was complemented by their teacher’s critical pedagogy in the tutorial system that was in place during Guha’s tenure at Sussex. This small-scale tutorial teaching is long gone in today’s neoliberal academic teaching machine which crams large numbers of students (many of whom must work multiple jobs alongside their studies to pay high university fees and accommodation rent) into lecture halls and seminar rooms for more transactional modes of education.

It would appear Guha’s time at Sussex was spent somewhat in the shadows, confining himself to reading and teaching. As Partha Chatterjee recalls, “during this time he did not publish any academic article or books, he would even largely avoid going to conferences. Basically, he was in a self-imposed exile from the professional community of historians” [8]. University of Sussex Emeritus Professor of Geography Tony Binns corroborates this, sharing the following personal reflections in an email to me (24 October 2023):

“During my first 5 years or so (1975-1980) I had an office on level 2 in AFRAS (Arts C) opposite Ranajit Guha. I remember him being a quiet and unassuming person who spent most of his time in his office and the library and was rarely seen socialising in the school common room. I guess he must have been in his fifties then? I arrived just after David Pocock (Anthropology) stepped down as Dean and Ieuan Griffiths (Geography) took over. There was clearly some tension between Guha and Pocock, and I remember Griffiths saying he had difficulty dealing with him. I think Ranajit Guha was probably a rather marginalised figure in AFRAS and I don’t recollect him being promoted or being a member of key committees. But he was always pleasant to me when we met in the corridor. I was rather shocked (and greatly impressed) in later life to discover that Guha was such a leading light and key thinker in the Subaltern Studies group.”

Tony Binns

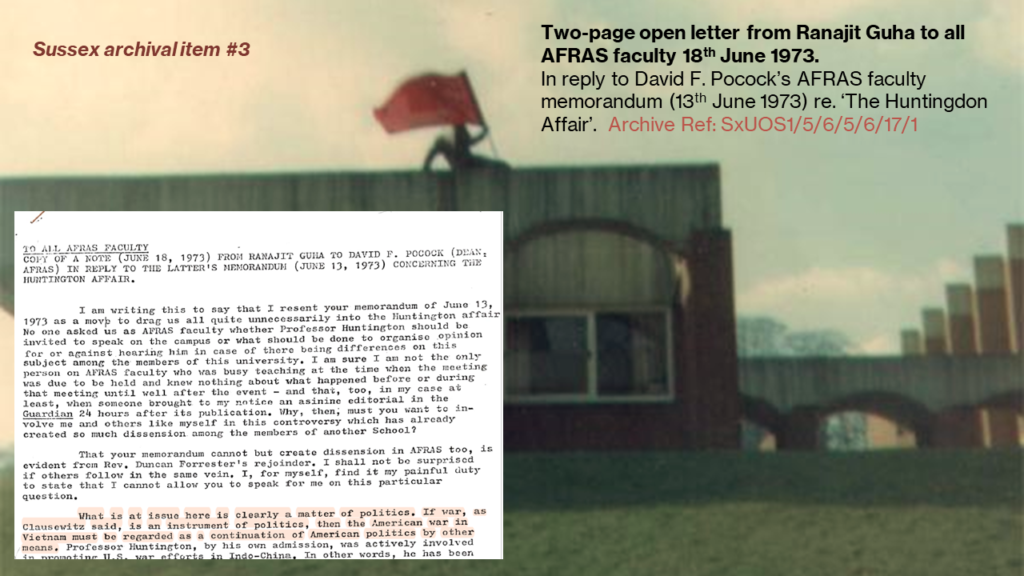

- UoS Archival item #3: a typescript letter by Guha with the following heading: TO ALL AFRAS FACULTY: COPY OF A NOTE (JUNE 18, 1973) ADDRESSED TO DAVID F. POCOCK (DEAN, AFRAS) IN REPLY TO THE LATTER’S MEMORANDOM (JUNE 13, 1973) CONCERNING THE HUNTINGDON AFFAIR.

This quite remarkable two-page letter testifies to Guha’s moral and intellectual integrity and acerbic fearlessness to speak truth to power in matters of conscience. It regards the furore that broke out on the Sussex campus when in Summer 1973 a group of student union activists from the Indo-China Solidarity Committee prevented American political scientist Samuel P. Huntingdon, visiting from the US, from giving his guest lecture, on the grounds of his imperialist ideology and complicity with state violence via his work with the Pentagon during the Vietnam War. The students had been refused the right to publicly challenge him at the lecture so decided to use peaceful direct action tactics instead and the lecture was cancelled[9]. The protests hit the national headlines, with newspapers and politicians from both sides of the political spectrum criticising Sussex for threatening academic freedom and freedom of speech.

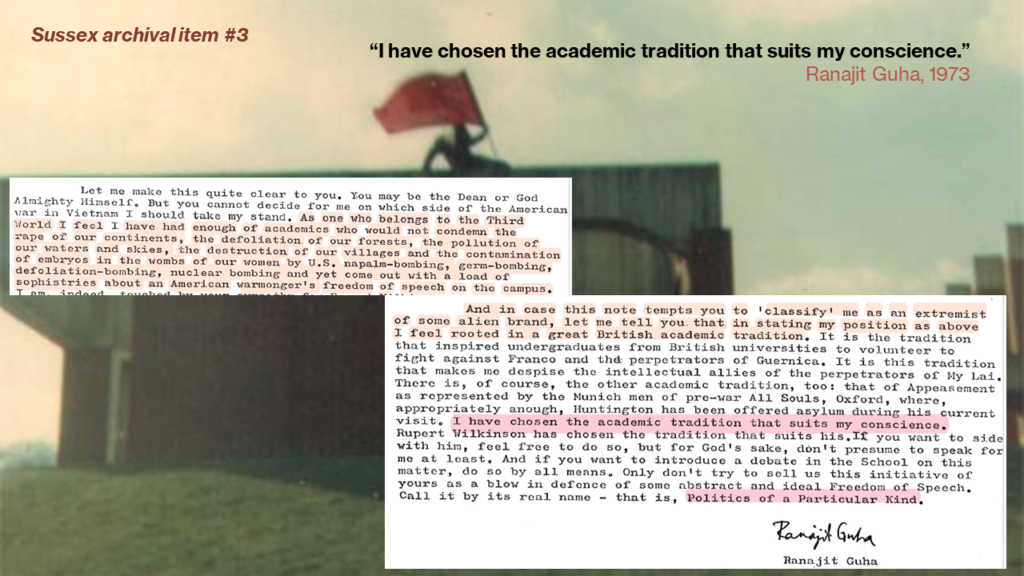

Inevitably, the students and staff on both sides of the debate were predominately from White Western backgrounds. Guha’s letter responds to having been unwillingly dragged into this affair by Dean Pocock apparent insistence that all AFRAS faculty should implicitly rally together on the side of freedom of speech to appease the establishment. I will share a few choice sentences from Guha’s polemical rejoinder here.

“What is at issue here is clearly a matter politics. If war, as Clausewitz said, is an instrument of politics, then the American war in Vietnam must be regarded as a continuation of American politics by other means. […]

Let me make this quite clear to you. You may be the Dean or God Almighty Himself. But you cannot decide for me on which side of the American war in Vietnam I should take my stand. As one who belongs to the Third World I feel I have had enough of academics who would not condemn the rape of our continents, the defoliation of our forests, the pollution of our waters and skies, the destruction of our villages and the contamination of embryos in the wombs of our women by U.S. napalm-bombing, germ-bombing, defoliation-bombing, nuclear bombing, and yet come out with a load of sophistries about an American warmonger’s freedom of speech on the campus. […]

And in case this note tempts you to ‘classify’ me as an extremist of some alien brand, let me tell you that in stating my position as above I feel rooted in a great British academic tradition. It is the tradition that inspired undergraduates from British universities to volunteer to fight against Franco and the perpetrators of Guernica. It is this tradition that makes me despise the intellectual allies of the perpetration of My Lai. There is, of course, the other academic tradition, too: that of Appeasement as represented by the Munich men of pre-war All Souls, Oxford, where, appropriately enough, Huntingdon has been offered asylum during his current visit. I have chosen the academic tradition that suits my conscience. Rupert Wilkinson has chosen the tradition that suits his. If you want to side with him, feel free to do so, but for God’s sake, Don’t presume to speak for me at least. And if you want to introduce a debate in the School on this matter, do so by all means. Only don’t try to sell us this initiative of yours as a blow in defence of some abstract and ideal Freedom of Speech. Call it by its real name – that is, Politics of a Particular Kind.” – Signed by hand, Ranajit Guha.

I was moved and impressed to read the strength of Guha’s voice here, which brought the quiet clinical atmosphere of the archival reading room to life with its fiery message. Guha’s letter asserts a strong lesson for those both above and adjacent to him in the academic hierarchy, and I imagine gave inspiration to any students who may have happened to see it. It certainly holds a lot of powerful and timely resonance for today’s neo-colonial wars, both in terms of culture wars manufactured by right-wing political and media elites both in Britain and in many global contexts, as well as of course in the present catastrophic genocidal attacks in Palestine and international state violence and censorship that is escalating at a devastating scale by the day.

Question 2: Ranajit Guha’s approach to history has in several ways involved railing against the domination of top-down approaches to history, and suggesting alternatives to the often violent, unjust and monolithic statist narratives of the past. As a scholar interested in radical history, how do you perceive Guha’s contribution to the Social Sciences education in Sussex, as may be read from the university archives? What new readings or methodologies did Guha introduce?

I think I have already partially answered this question with my analysis of Guha’s course syllabus above. If I had the chance to be a student on Guha’s Imperialism Special Subject course today I would embrace it, as I am sure it would help me deepen and broaden my knowledge of how Empire is at the root of everything I try to understand and challenge in my work.

I am not a trained historian myself, having completed a BA in Literature and Philosophy, an MA in Cultural Studies, and a PhD in Sociology; however there has been a strong historical focus threaded throughout my interdisciplinary research and professional work in libraries and archives over the past two decades. This has led to commencing my current position as a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow in the School of Global Studies (Department of International Development), which takes a historical anthropological approach to exploring the question of what ‘decolonising the university’ means through the prism of the library, archival memory, oral histories and transnational legacy relationships between Sussex and academic bodies of knowledge and resistance in Britain’s former colonies.[10] I strive to take a grounded, ‘bottom-up’ and epistemically disobedient[11] approach to this work in collaboration with scholars, activist, librarians and archivists working against the colonial grain of knowledge production.

I think we can infer from both Guha’s Imperialism syllabus and his letter to Pocock that his contributions to developing radical history in the interdisciplinary social studies programmes at Sussex were ways of working through what he later defined in his book A Rule of Property for Bengal: An Essay on the Idea of Permanent Settlement (published in 1982 the year he left Sussex), as the “epistemological paradox”: the ways in which bourgeois and statist forms of knowledge are hell-bent on structurally transforming and maintaining master-slave relations between Imperial rulers and their semi-feudal subject. So the idea of ‘permanent settlement’ here pertains not only to land and property, but also to what constitutes legitimate bodies of knowledge and ways of life and forms of economic and social reproduction[12]. In this sense, I’d like to suggest that what Guha was contributing to Sussex through his teaching and research was a rigorous decolonial unsettling of the British episteme, or ‘map of learning’ if you will, as an insider-outsider disrupting these terrains from within. Today, Sussex’s corporate strategy includes the phrase “dare to disrupt”, but from what I have observed here, very few faculty actually dare or are able to do this in the ways that Guha seemed to have been able to.

As Rudrangshu Mukherjee argues in his eulogy:

“Integral to almost everything that Guha wrote was the idea of a critique – radical doubt regarding all forms of received wisdom. His critique of colonial and elite dominance led him to ask the question: could there be an Indian history of India? A mode of history writing that would be free from the disciplinary boundaries fashioned by western historiography, especially colonialist historiography. Such questions took him to the study of literature and texts.”[13]

One of Guha’s first students at Sussex was Richard Price, who recalls the pedagogical impact of the way in which his teacher:

“treated history as something that could be thought about conceptually, as a process, and not as just a narrative progression. His undergraduate course on European Imperialism, for example, was not the usual course that began with the age of explorations. It began instead with the theorists of empire and then went on to study the British, French and German cases within that context. Ranajit was the first person to teach me that the problems of history could be conceptual, rather than being a problem of events.” [14]

The archived course syllabus lists the eighth and final topic of the curriculum as ‘The Propagation of the Imperial Idea’, broken into four parts: (8.1) The Thinkers: Seely, Froude, Dilke; Mary Kingsley; (8.2) The Writers: Kipling; Austin; Henly; Henty; Haggard; (8.3) Indoctrination of the Youth: Clubs and Brigades, Associations; (8.4) The Press. The Music Hall The Patriotic Crowd.

The way in which this course is structured and concludes goes way beyond any traditional academic approaches to teaching history, expanding into the realms of what would later become the field of Cultural Studies, pioneered by the likes of Raymond Williams and Stuart Hall in the British context. The inclusion of literary authors and cultural texts on the reading list also testifies to Guha’s intellectual formation at the intersections of history, philosophy, and literature, on which he reflects in his later writings, notably History at the Limit of World-History (2002). In the Epilogue of this book, titled ‘The poverty of Historiography – a Poet’s Reproach’, Guha offers a deep engagement with the critique of the norms of the discipline of history via his muse Rabindranath Tagore. He concludes with the wish that historiographers would have heeded Tagore’s critical and creative literary approach to distilling the everyday realities of historicity, lamenting however that that in the sixty years since, the “statist blinkers” of the majority of historians remain firmly in place.[15]

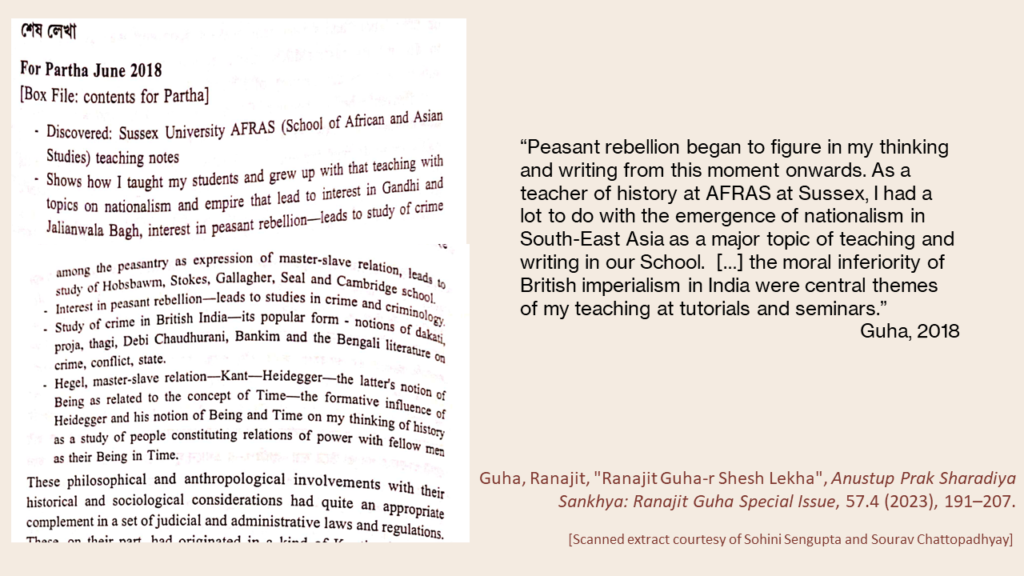

Question 3: At the age of 94, in one of his last writings (left in the care of Prof. Partha Chatterjee), Guha described some of the teaching notes that he prepared for his teaching in AFRAS (School of African and Asian Studies), University of Sussex. He wrote that as a teacher in AFRAS, he extensively taught nationalism in South-East Asia, and was driven to think about liberalism, Gandhian philosophy, and most significantly, the “peasant farmer’s” appearance at both national and international levels. How far does Guha’s declaration about his teaching notes resonate with the materials uncovered in the Sussex archives?

This final reflective text of Guha’s is a fascinating archival window on his time at Sussex, which sheds remarkable retrospective light on how this shaped the subsequent half-century of his intellectual development.

His bullet-pointed list of teaching notes (much like his detailed Imperialism Special Subject syllabus) indicates a complex interweaving of a diverse range of transdisciplinary and transnational sources and concepts that informed his teaching. “These philosophical and anthropological involvements with their historical and sociological considerations”, he notes, “had quite an appropriate complement in a set of judicial and administrative laws and regulations”, in this case the series of numbered box files on his bookshelves containing Sadr Diwani Adalat Papers (SDAP), the archives of the native administrative governors of the Supreme Court of Revenue British India in the provinces. Guha reflects on how such archival evidence of “the official mind” were part of a trend in historiography and area studies in the 1960s, in both Britain and India (Derridean Archive Fever springs to mind[16]), yet these approaches were still, he suggests, reproducing a statist historiographic methodology.

What Guha was doing by critically interweaving the Western European canon with sources like the SDAP archives was of an “altogether different attitude – that is, the Gandhian ideal of sharing he fate of the village poor and distancing oneself as far as possible from the loyalist elite in one’s way of life”, with the tutorial system at Sussex offering an opportune vehicle for the application of moral and academic integrity and anti-imperialism in his teaching.

Relating this to the third UoS archival source detailed in my answer to your first question, namely the polemical missive to his AFRAS boss David Pocock, we can begin to see how the personal, the professional and the political – as well as the national and the international – were holistically intertwined and rooted in Guha’s academic practice at Sussex. The majority of his colleagues here were from the Oxbridge elite, and hence significantly rattled by the threat to their privileged ‘academic freedom’ by the new generation of student activists railing against American Imperialism on campus[17]. Guha’s retort to Pocock addressed to the whole AFRAS faculty demonstrates how he refused to be constrained by false binaries of being either for or against ‘freedom’, whether it be of the academic or public discourse variety, since this framing disavows the question of the political and colonial biases inherent in such elitist constructions of freedom, which he bluntly reveals as simply “Politics of a Particular Kind”.

The text you have shared with me from Guha’s personal archive (care of Partha Chatterjee), can I think be read itself as a counter-archival metanarrative of the dialectical approach that he embodied in his praxis. The content of this reflective text was formed dialogically with the imperial state archives that were key sources for his early research. Hence the text can be understood as a composite form of archival-ethnographic memory, or in other words, a re-collecting of intellectual development and political consciousness, and how and why he transmitted those lessons to those he taught and thought with.

Question 4: Finally, a more general question: as someone engaged with library sciences and archival handling, what do you think about institutional memory? How far does it memorialise the constituents of an institution? Are there structures of prioritisation involved in the making and preservation of institutional archives? What do archival absences have to tell us, in these contexts?

This is a big and important question that is central to my work yet which I am still quite early in my journey of addressing. Archival institutions and their contents are not neutral, and part of that non-neutrality lies in what they do not contain (silences, absences) as well as what they do. Additionally, as Valerie Johnson warns, drawing on Vern Harris’s archival practice with the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, archives can be populated with “false voices” misinformation produced by the state[18]. As Michel-Rolph Troulliot warns, the commonplace “storage model of memory-history” as a form of recollection of important past experiences or evidence (a model that archival institutions tend to embody both literally and figuratively, for example the large warehouse-like building of the University of Sussex archival repository is called The Keep), as this model rests upon an antiquated scientific Eurocentric paradigm replete with unreliable narrators.[19] Troulliot’s methodology is rather to focus on the ways in which history reveals itself through how power is produced and reproduced through particular narrative processes of intelligibility. In an institutional archival setting, these processes are not only produced by the work of historians, but by the traditions and practices of archivists themselves, which are built into the infrastructures of archival storage, cataloguing and retrieval via mediating hierarchies that are rooted in colonial systems of managing information and knowledge.

I have begun to write about this on my research blog with references to Sussex’s institutional archive, which I argue is structured and conditioned by enduring colonial mechanisms of ordering and instituting cultural memory and information in an academic context. Imperialism continues to structure and fracture our institutions, records and cultural heritage, thereby silencing subaltern voices and whitewashing the indigenous histories of the global majority. I am particularly inspired by the Caribbean archivist and cultural theorist Stanley H. Griffin, argues that decolonising archives should necessarily be a noisy activity, disrupting Eurocentric and colonial epistemic silences and violences. Griffin likens institutional archives to the lifeblood of an institution, and in the many institutional contexts wherein much blood has been spilled through the violence of colonialism, we need to listen to how this blood beats through the rhythms of the records: “the repressed and silenced in the archival records will agitate and haunt until full recognition and acknowledgement of its informational and enduring values are secured. These noises demand the attention of both archivist and researcher alike.”[20] In my work this attention involves tuning out (like a radio) what I call white noise in the archive: the dissonant interference of the whiteness of institutional machinery and memory in constructing what and how we re-collect and recover diverse knowledges.[21] For archivists and scholars collaborating on this work, we need to tune in to reparative and liberatory archival description[22] to make catalogue access points more inclusive, nuanced, and representative, as well as pro-active collecting policies that imaginatively attend to unequal frequencies, channels, mediums and platforms of subaltern voices.

References

Akoleowo, Victoria Openif’Oluwa, ‘Critical Pedagogy, Scholar Activism and Epistemic Decolonisation’, South African Journal of Philosophy, 40.4 (2021), 436–51 <https://doi.org/10.1080/02580136.2021.2010175>

Briggs, Asa, ‘Maps of Learning’, New Statesman (1957), 61 (1961), 338-

Caswell, Michelle, Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work, Routledge Studies in Archives (Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2021) <https://sussex.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/44SUS_INST/p3abpr/alma99995851002461>

Corble, Alice, ‘Storying the Postcolonial Library’, Iniva, 2013 <https://iniva.org/blog/2013/05/23/guest-blog-post-storying-postcolonia/>

———, ‘“Libraries of Racial Discovery”: Transatlantic Hidden Histories and the Politics of Memory’, Decolonial Maps of Library Learning, 2023 <https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/decolonialmapsoflearning/2023/07/27/libraries-of-racial-discovery-transatlantic-hidden-histories-and-the-politics-of-memory/>

———, ‘New Leverhulme ECR Fellowship: Evolving Maps of Decolonial Learning at Sussex and Beyond’, Decolonial Maps of Library Learning, 2023 <https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/decolonialmapsoflearning/2023/10/19/announcing-my-new-leverhulme-ecr-fellowship-and-evolving-maps-of-decolonial-learning-at-sussex-and-beyond/>

Cragoe, Matthew, ‘Sussex: Cold War Campus’, in Utopian Universities: A Global History of the New Campuses of The 1960s, ed. by Miles Taylor and Jill Pellew (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2020), pp. 56–71.

Daiches, David, The Idea of a New University: An Experiment in Sussex (London: Andre Deutsch, 1964)

Damodaran, Vinita, ‘Obituary: Professor Ranajit Guha’, The University of Sussex, 2023 <https://www.sussex.ac.uk/broadcast/read/61233>

Derrida, Jacques, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (University of Chicago Press, 1996)

Edgley, Roy, ‘Thought and Action in the Huntingdon Affair: Freedom of Speech and Academic Freedom’, Radical Philosophy, 010.Spring (1975) <https://www.radicalphilosophyarchive.com/article/thought-and-action-in-the-huntingdon-affair/> [accessed 25 October 2023]

Fuh, Divine, ‘Disobedient Knowledge and Respect for Our African Humanity’, University of Cape Town News, 2022 <http://www.news.uct.ac.za/article/-2022-08-24-disobedient-knowledge-and-respect-for-our-african-humanity> [accessed 15 August 2023]

Griffin, Stanley H., ‘Noises in the Archives: Acknowledging the Present yet Silenced Presence in Caribbean Archival Memory’, in Archival Silences, ed. by Michael Moss and David Thomas (London: Routledge, 2021)

Guha, Ranajit, A Rule of Property for Bengal: An Essay on the Idea of Permanent Settlement (Orient Blackswan, 1982)

———, History at the Limit of World-History (New York ; Chichester: Columbia University Press, 2003)

———, The Small Voice Of History (Ranikhet: Orient BlackSwan, 2010)

Mukherjee, Rudrangshu, ‘Ranajit Guha (1923-2023): The Bengali Vessel Lies Emptied of Its History and Learning’, The Telegraph India Online, 1 May 2023 <https://www.telegraphindia.com/opinion/ranajit-guha-1923-2023-the-bengali-vessel-lies-emptied-of-its-history-and-learning/cid/1933585>

Mukherjee, Somak, ‘Ranajit Guha, India’s Oldest Living Historian’, Frontier, June 2022 <https://www.frontierweekly.com/articles/vol-54/54-51/54-51-Ranajit%20Guha%20Indias%20Oldest%20Living%20Historian.html>

Price, Richard, ‘90th Birthday Tributes to Ranajit Guha’, Permanent Black, 2013 <https://web.archive.org/web/20230205103926/https://permanent-black.blogspot.com/2013/05/short-birthday-tributes-to-ranajit-guha.html>

Subrahmanyam, Sanjay, ‘Grey Eminence’, NLR/Sidecar, 16:02:07 UTC <https://newleftreview.org/sidecar/posts/grey-eminence>

Shetty, Sandhya, and Elizabeth Jane Bellamy, ‘Postcolonialism’s Archive Fever’, Diacritics, 30.1 (2000), 25–48 <https://doi.org/10.2307/1566434>

Sutherland, Tonia, and Alyssa Purcell, ‘A Weapon and a Tool: Decolonizing Description and Embracing Redescription as Liberatory Archival Praxis’, The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion (IJIDI), 5.1 (2021), 60–78 <https://doi.org/10.33137/ijidi.v5i1.34669>

Thomas, David, Simon Fowler, and Valerie Johnson, The Silence of the Archive, Principles and Practice in Records Management and Archives Series (London: Facet Publishing, 2017)

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston, Mass: Beacon, 1997)

University of Sussex, ‘University of Sussex Collection’, The Keep. <https://www.thekeep.info/collections/getrecord/GB181_SxUOS1>

[1] University of Sussex, ‘University of Sussex Collection’ [GB181_SxUOS1], The Keep.

[2] Ranajit Guha, The Small Voice of History: Collected Essays ((Ranikhet: Orient BlackSwan, 2010).

[3] Victoria Openif’Oluwa Akoleowo, ‘Critical Pedagogy, Scholar Activism and Epistemic Decolonisation’, South African Journal of Philosophy, 40.4 (2021), 436–5.

[4] Asa Briggs, ‘Maps of Learning’, New Statesman (1957), 61 (1961), 338-.

[5] David Daiches, The Idea of a New University: An Experiment in Sussex (London: Andre Deutsch, 1964).

[6] Matthew Cragoe, ‘Sussex: Cold War Campus’, in Utopian Universities: A Global History of the New Campuses of The 1960s, ed. by Miles Taylor and Jill Pellew (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2020), pp. 56–71.

[7] Rudrangshu Mukherjee, ‘Ranajit Guha (1923-2023): The Bengali Vessel Lies Emptied of Its History and Learning’, The Telegraph India Online, 1 May 2023.

[8] cited in Somak Mukherjee, ‘Ranajit Guha, India’s Oldest Living Historian’, Frontier, June 2022.

[9] Roy Edgley, ‘Thought and Action in the Huntingdon Affair: Freedom of Speech and Academic Freedom’, Radical Philosophy, 010.Spring (1975).

[10] Alice Corble, ‘New Leverhulme ECR Fellowship: Evolving Maps of Decolonial Learning at Sussex and Beyond’, Decolonial Maps of Library Learning, 2023.

[11] Divine Fuh, ‘Disobedient Knowledge and Respect for Our African Humanity’, University of Cape Town News, 2022.

[12] Ranajit Guha, A Rule of Property for Bengal: An Essay on the Idea of Permanent Settlement (Orient Blackswan, 1982), p. 6.

[13] Rudrangshu Mukherjee.

[14] Richard Price, ‘90th Birthday Tributes to Ranajit Guha’, Permanent Black, 2013.

[15] Ranajit Guha, History at the Limit of World-History (New York ; Chichester: Columbia University Press, 2003), p. 94.

[16] Sandhya Shetty and Elizabeth Jane Bellamy, ‘Postcolonialism’s Archive Fever’, Diacritics, 30.1 (2000), 25–48; Jacques Derrida, Archive Fever: A Freudian Impression (University of Chicago Press, 1996).

[17] Edgley.

[18] David Thomas, Simon Fowler, and Valerie Johnson, The Silence of the Archive, Principles and Practice in Records Management and Archives Series (London: Facet Publishing, 2017), p. 102.

[19] Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston, Mass: Beacon, 1997), p. 14.

[20] Stanley H. Griffin, ‘Noises in the Archives: Acknowledging the Present yet Silenced Presence in Caribbean Archival Memory’, in Archival Silences, ed. by Michael Moss and David Thomas (London: Routledge, 2021), p. 85.

[21] Alice Corble, ‘“Libraries of Racial Discovery”: Transatlantic Hidden Histories and the Politics of Memory’, Decolonial Maps of Library Learning, 2023.

[22] Tonia Sutherland and Alyssa Purcell, ‘A Weapon and a Tool: Decolonizing Description and Embracing Redescription as Liberatory Archival Praxis’, The International Journal of Information, Diversity, & Inclusion (IJIDI), 5.1 (2021), 60–78; Michelle Caswell, Urgent Archives: Enacting Liberatory Memory Work, Routledge Studies in Archives (Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2021).

[…] of this article have been adapted from an earlier blog by the author: Corble, A. (2023) ‘Re-collecting Ranajit Guha through a counter-archival lens’, Decolonial Maps of Library Learning, 3 […]