APRIL 9, 2020

Former BBC Monitoring Service employee’s journals found and adapted into a new web series.

“I don’t know what the future may bring, but I think there are fairly good prospects in the BBC. After two years there, I have a good chance of getting on the established staff and thus qualifying for a pension. So, perhaps for the first time in my life, I am in a good steady job at last.” Dick Perceval, 12th June 1950.

My name is Becky Edmunds and I am an artist filmmaker.

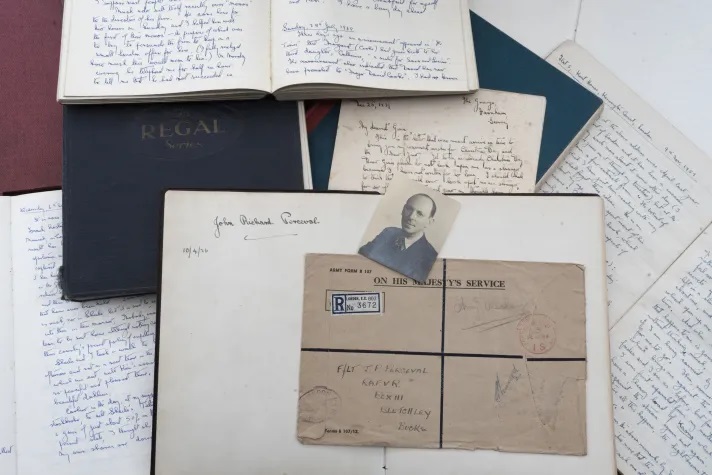

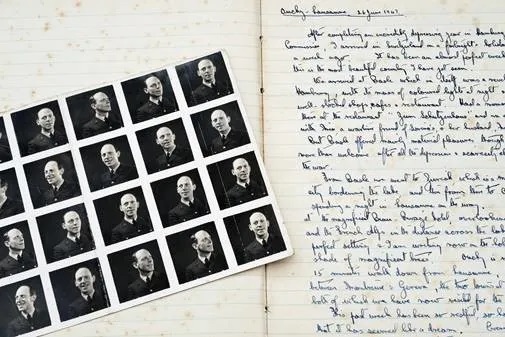

22 years ago, in Brighton, I found a box of journals in a pile of rubbish by the side of the road. Written by a man called Dick Perceval, they cover the 50 years from 1925 – 1975. They are an extraordinary record of the life of an ‘ordinary’ man.

From 1950 to 1964, Dick worked as a report writer for the BBC Monitoring Service. Previously, he had worked as a journalist, until the outbreak of World War Two interrupted his career. After volunteering to join the Royal Artillery as a Gunner and spending six months on anti-aircraft guns at Enfield Lock, Dick was suddenly summoned to the War Office to be interviewed for a job. He had no idea what the job was, or why they had chosen him, but as a result of the interview he was recruited to work at Bletchley Park, as part of the team in Hut 3, where Enigma messages sent by the German Army and Air Force were decrypted, translated and analysed for vital intelligence.

At the conclusion of the war, Dick went to Hamburg, working in political intelligence as part of the Allied Control Commission, before returning to the UK to take up a job with the BBC Monitoring Service.

On the 12th June 1950, he writes,

“I handed in an application to the BBC in answer to an advertisement of theirs for “Report Writers” in their monitoring service at Caversham. Qualifications were a knowledge of foreign affairs and journalistic experience – salary, rising by annual increments of £45, up to £995 a year.”

Dick spoke fluent German, having spent some of his childhood in Germany. In 1925, he attended the University of Berlin on a one year foundation course, and his connections to Germany were further solidified through his marriage to Sorina Erbes – a German woman, 23 years his senior, and a fabulously flamboyant character. More of her later…

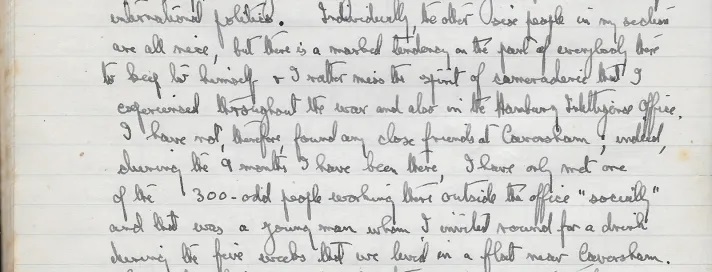

Dick started at the Monitoring Service in the Russian section and not, as he expected, in the German section. His journal gives a sense of the working environment at Caversham.

“Individually, the other six people in my section are all nice, but there is a marked tendency on the part of everybody there to keep to himself and I rather miss the spirit of camaraderie that I experienced throughout the war, and also in the Hamburg intelligence office. I have not therefore found any close friends at Caversham and, indeed, during the nine months I have been there, I have only met one of the 300 odd people working there outside the office socially, and that was a young man whom I invited round for a drink during the five weeks that we lived in a flat near Caversham. My work is entirely writing, most of which I do alone in a typing cubicle, and that suits me quite well.”

Dick loved writing. As a young man he had dreams of being a great author. Or Prime Minister. He couldn’t quite decide which. He came from a very privileged background and as a young man believed himself to be a genius. He was also a Romanticist, and his attempts at writing novels, which he documents in his journals, resulted in love stories with tragic and melodramatic plot lines, based on the people he surrounded himself with. Which brings me back to Sorina.

Dick met Sorina in 1931, when he was 22 years old, and was captivated by her. She was 44, married with three sons aged 12, 16 and 19. Following her divorce, her remarriage and a second divorce, Dick and Sorina were married in 1936, when he was 26. It was the biggest mistake of his life. It was a desperately unhappy marriage, his family cut him out of any inheritance and he didn’t have any children – a fact that caused him great sadness later.

Sorina died in 1960, of a heart attack and in his arms. After a couple of journal entries in which he reflects movingly about her death and on their life together, Dick stops writing until 1964.

“It is with great hesitation that I start writing a journal again, after an interval of about three years, I believe. During that period, I have had little time, and less inclination, to do this, although much that is of great importance to me has happened during these three years.

On 5 September 1961, I married again. I married Sheila, whom I had known for some years previously at the BBC, where she also worked before our marriage. It has been a most happy marriage and a great blessing in my life.” July 25th 1964

With the support of Sheila, Dick took early retirement from the BBC in 1964. He goes on –

“My work at the BBC continued much as before, the last few years being spent in the Far Eastern section of the Monitoring Service, which I much preferred to the Russian and East European sections I had previously worked in, partly because my own past experience in the Far East made it much more interesting to me, and partly because the people I worked with were more congenial to me. It was more interesting, but still not very interesting. The truth is that my heart was never really in my work at the BBC, most unfortunately. Whether this was my fault or not it is difficult to know. Except for one, comparatively brief period there, when I worked in the East European section, I was reasonably happy or at least as much so as one can expect to be when one’s heart is not in one’s work. But this is the fate of the vast majority and I was one of them.”

He reflects on whether he achieved ‘success’. He says that he started with the BBC on £750 per year and this rose to over £2000 by the time he left, but the increase was due to automatic processes, rather than through promotion, so he considered that his career was neither success nor failure.

“Neither a failure nor a success, alas, just about sums up the whole of my career to date, in my opinion, and that is the cause of the disappointment in my life that I feel. The main cause – but if I feel disappointed, this does not mean that I feel embittered. Not at all. I have long asked myself what true success in life may be, and how it can be judged. It is a question that fascinates me. I realised long ago that success cannot be measured merely by what a man earns, nor necessarily by what rank, position or grade he may rise to.”

In 2018, I visited Caversham to look at Dick Perceval’s staff file, which had been kept in the archives. The first document in the file is from 1938, 10 years before he started working there. It is a letter to the editor of the BBC magazine The Listener, to enquire if there were vacancies. The final document is his leaving note. Under the title Assessment of Career (including efficiency, conduct and any special aptitudes), there is a note that reads,

“Mr Perceval opted for Voluntary Early Retirement after nearly 16 years of service as Report Writer, Monitoring Service. On many occasions he acted temporarily as Senior Report Writer.

His period of service shows he was always conscientious and hardworking.” It is not an effusive report!

I have been working with sound designer Scott Smith and performer Gerard Bell to adapt entries from Dick’s journals into a series of short films that are available, for free, as a web series called To Be Continued. Dick Perceval’s story is brought to life through the re-appropriation of archive footage. A cast of hundreds is drawn from old Hollywood films, public information broadcasts, cine club creations and home movies.

Dick Perceval’s journals are fascinating. He writes about the life events that we all experience – falling in love, heartbreak, loss, disappointment, acceptance and of world events – war, elections, times of uncertainty, even a European Referendum. Dick’s journals shine a unique light onto the 20th century.

To catch up with the series so far (ideal for a lockdown) visit https://www.tobecontinued.online/series-episodes

Subscribe to the series for free to receive links to further episodes delivered to your email address, on the same date that Dick wrote the journal entry. The series, which began on January 1st will continue till December 31st 2020.

April 2020

Leave a Reply