It is noh mistri

Wi mekkin histri

(Linton Kwesi Johnson, 1984)

Introduction

The thing about making history, especially institutional history, is that the truth of lived experience often gets disfigured, silenced, or buried. Such archival asymmetries were addressed by a brilliant line-up of speakers at the launch of the Black at Sussex programme, which took place at the Black Cultural Archives (BCA) in Windrush Square on Thursday 22nd September 2022. These speakers shared recollections of the political and creative cauldron of late-twentieth-century Black British cultural life, and the role played by University of Sussex in the educational chapters of their stories.

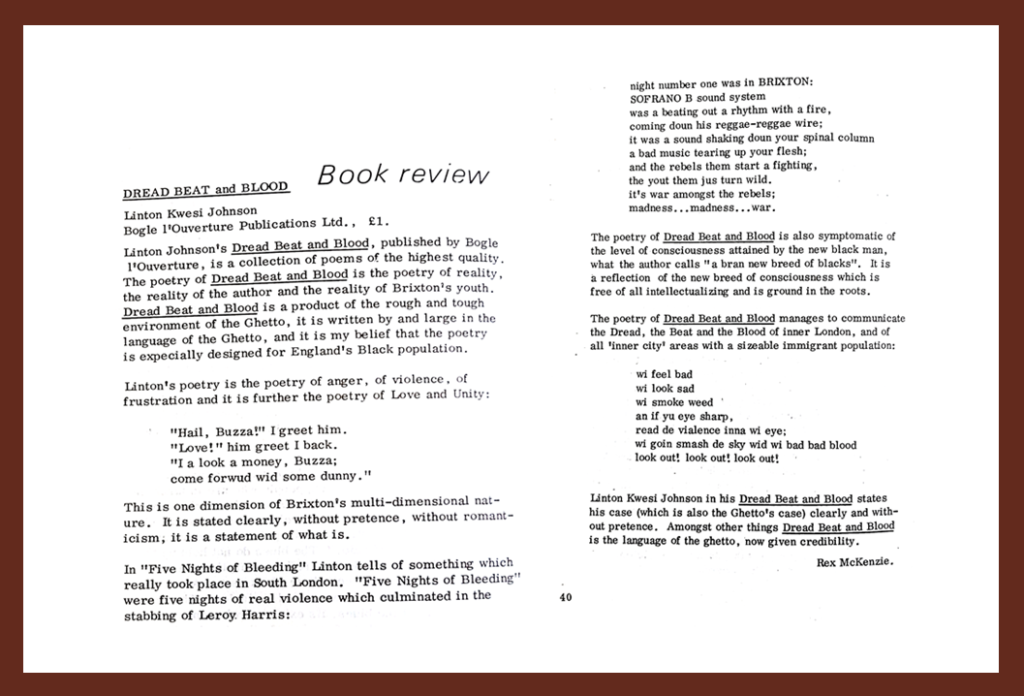

The album Making History by poet Linton Kwesi Johnson (LKJ) was recorded and released in London in 1984, with lyrics that reflect a national and global condensed moment of political, economic and social crises. There are more than a few echoes that resonate with today’s crisis-ridden landscape. The mesmeric dub poetry beat of LKJ’s music, which includes tracks commemorating the New Cross Massacre and the Brixton Uprising of 1981, resonates with the rhythms of resistance and cycles of history that continue on our streets and in our places of work and learning today. As LKJ reflected on his time contributing to the Race Today Collective in the 1970s-80s, channelling the mantra of Black Panther Bobby Seale, the rallying call then (and many present-day anti-racist activists and cultural producers will agree endures today) was to “Seize The Time” (in Field, Bruce and Hassan, 2019, p. 8).

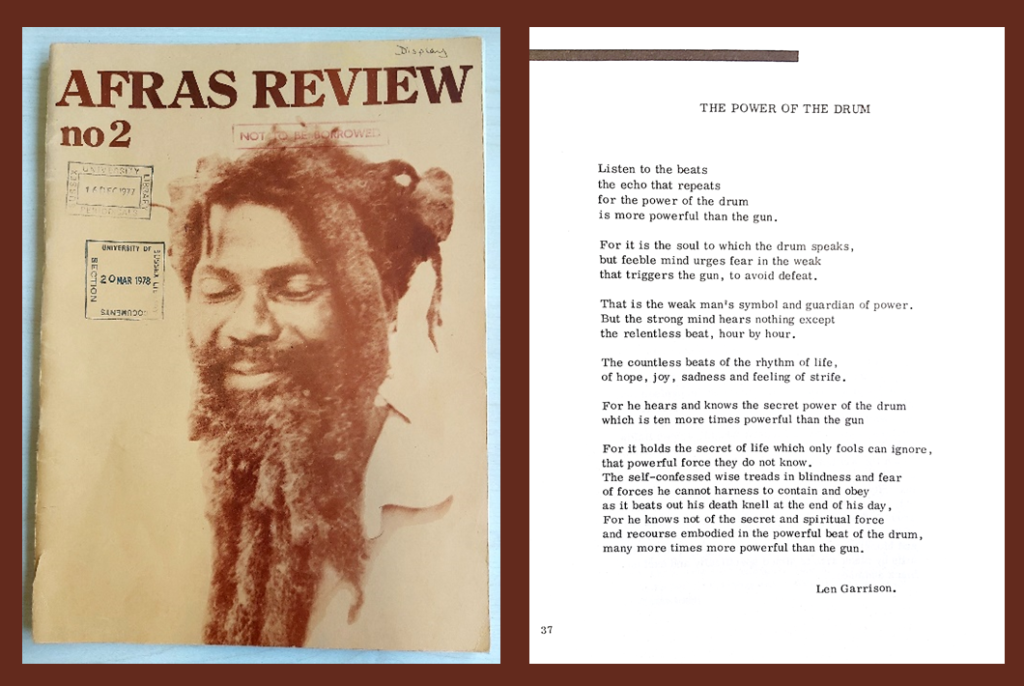

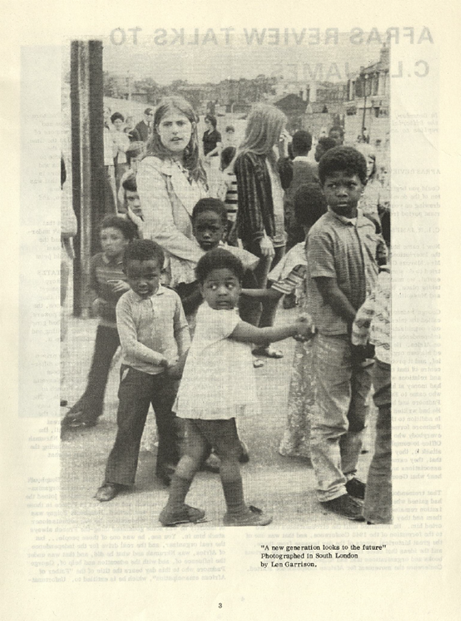

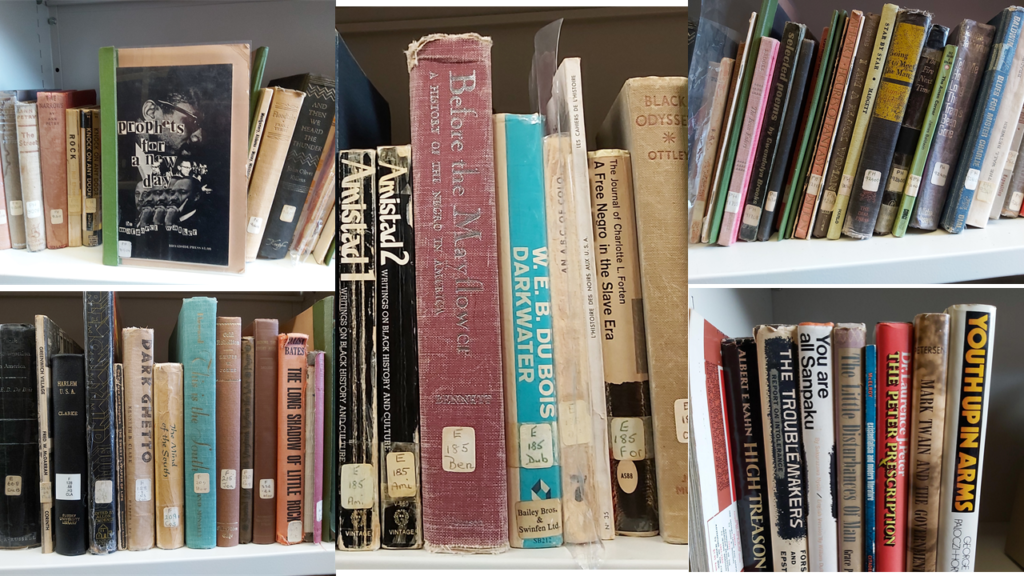

Today as I leaf through the archived print copies of the AFRAS Review, a periodical produced by Black and Asian students and staff at University of Sussex School of African and Asian Studies (AFRAS) in the 1970s (one of whom was Len Garrison who went on to co-found the BCA) I see and hear these rhythms of resistance indelibly inked on the page.

As someone who lived, worked, and studied in the densely populated multicultural inner London boroughs of Hackney and Lewisham for close to two decades before my move to Brighton for a job at University of Sussex Library in 2019; it felt good to be going back to my old stomping ground for a community event in inner-city South London, a place which significantly contrasts with the rural, rarefied, and white-dominated spaces of campus life in Falmer. I hope that future Black at Sussex events and activities can find embedded connections and reach wider audiences with Black and diverse communities based in Brighton and Hove urban areas, where many of our students, staff and alumni live and work.

Black at Sussex is a five-year education and cultural inclusion and creative advocacy programme, which aims to improve the experience of Black students at Sussex, thereby acting on the university’s antiracist pledge and widening participation priorities. It intends to do this by showcasing and celebrating University of Sussex Black alumni and their contributions to public life via public art created and embedded on campus by Black photographers and curators, and a programme of critical discussion events about racialised educational experiences.

The Black at Sussex launch event was expertly facilitated by host Karina H Maynard, along with Lisa Anderson (BCA interim Managing Director). It opened with an address by University of Sussex’s new Vice Chancellor Sasha Roseneil, who celebrated the many Black Sussex alumni who have gone on to make major contributions to British cultural life as well as international arenas. She also acknowledged the much more dismaying fact that many Black Sussex students both in the past and the present suffer an isolating and exclusionary educational experience, suffering the harmful effects of racialised microaggressions and structural inequalities.

The line-up of speakers was impressive. Renowned photographers Charlie Phillips & Eddie Otchere talked in dialogue about their work photographing portraits of Sussex Black alumni, commissioned as part of the project. Valerie Kporye spoke about her experience as a current Sussex BA Philosophy & Literature student, and what she has learned and gained so far from her involvement in the development of Black at Sussex; in dialogue with Professor Martin Evans who talked about his motivations for developing the collaborative project. Poet and educator Jenny Mitchell spoke about her time as a student at Sussex in the 1980s and delivered a powerful poetry reading. Playwright and artist Michael McMillan and Afro-Queer artist and filmmaker Topher Campbell spoke about their early educational and activist experiences at Sussex and how this informed their creative careers. Finally, Marie Garrison spoke about the work of her late husband Len Garrison, photographer, educationalist, historian and co-founder of BCA (who sadly died in 2003), in particular his work as a photographer and educator documenting and developing diasporic lives and communities.

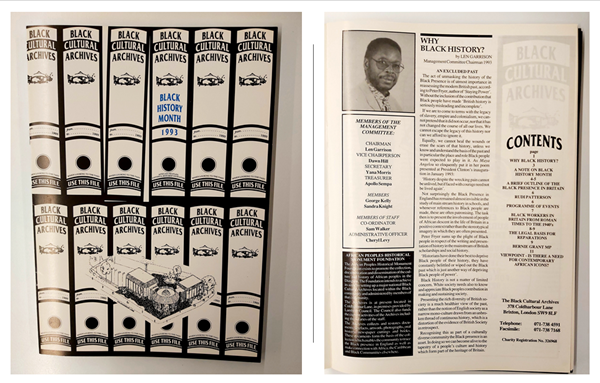

Black Cultural Archives

BCA is the only national heritage centre dedicated to collecting, preserving, and celebrating the histories of African and Caribbean people in Britain.

BCA grew out of a community response to a catalogue of racial injustices in the 1970s and 80s, including the New Cross Massacre (1981), in which 13 young Black people were killed in a house fire caused by a racist arson attack (for which there is still no justice and no peace); the Police and Criminal Evidence Act (1984); the underachievement of Black children in British schools; the failings of the Race Relations Act 1976; and the harmful impacts of racism against people of African and Caribbean descent in the UK.

These compounded structures of national and institutional racism were evidenced in the powerful work of Bernard Coard, who studied at Sussex in the late 1960s and in 1971 published the book How the West Indian Child Is Made Educationally Sub-normal in the British School System: The Scandal of the Black Child in Schools in Britain. Coard’s work was pivotal in the Black Education Movement in Britain and a landmark in a seismic moment in the history or racial justice struggles in Britain2. As John La Rose (Chairman of the New Cross Massacre Action Committee, political and cultural activist, poet, writer, and founder of New Beacon Books) remarked at a speech given at Brixton Civic Centre in February 1976 to mark the second anniversary of Race Today1, over time this movement sadly turned into “the decline of the black youth political organisations and the rise of internal neo-colonial practices directed at blacks, workers and middle strata” (Field, Bruce and Hassan, 2019, p. 16).

After graduating from his Sussex degree in African and Caribbean history in 1976, Len Garrison decided that Britain needed a space where members of the Black community, especially young people, could come and find positive historical and cultural representations of themselves. The Black at Sussex programme is designed to do just that and more at the University of Sussex.

Photography, Archiving and Power

The Black at Sussex launch event was titled Photography, Archiving and Power, and photographer David Mensah has powerfully captured moments and portraits of the event and its speakers and attendees. However, no official audio or video recording of the event was made, and to my knowledge there has not yet been a written review of it other than the University’s Internal Communications promotion of it3. It is this absence of a textual archiving of the event that prompted me to write this blog post, documenting it as an important moment in British Black history4.

The legendary photographer Charlie Phillips (OBE), described by historian Simon Schama as “the most important (yet least lauded) Black British photographer of his generation”, and his collaborator Eddie Otchere, described by The Financial Times as “the patron saint of British urban photography”, were the first guests to speak following Roseneil’s opening address. They talked about their commission to create a series of photographic portraits of Black Sussex alumni situated in locations of the subjects’ choosing. Phillips reflected how this project has made him realise how much “hidden talent” has come out of academia, which “the institution hasn’t properly explored or invested in”. He expressed hope that the programme will encourage the “best of British Black academics” to come forward and be given opportunities to have their contributions recognised and rewarded. He was pleased to be able to document this legacy, which adds to more than fifty years of his outstanding oeuvre documenting Black British life.

Phillips reflects in this moving film by Leo Buckley about his work, which was unjustly overlooked for decades:

When mi first came to England, living in London was a nightmare. I just thought I didn’t fit in. I started taking photographs, documenting the community I was growing up in. Hoping that one day, you know, when we go back to Jamaica, they’ll be all in an album and we can show what life was like in England. I thought I’d document our history. Tell our side of the story. But nobody wanted it at the time.

(Charlie Phillips – I was Always Here, Buckley 2022)

In dialogue with Charlie, Eddie Otchere reflected during the event on his work as the curator of the Charlie Phillips Heritage Archive, which he poignantly referred to in terms of handling “bodies in the archive”, conjuring a sense of both loss and vitality in the Black cultural visual historical record. Eddie has previously described his own photographic practice as bringing to life “dead materials” through hauntological mediations in the darkroom. The phrase that resounded most for me in his contributions to this event was “we need to add more bodies to the archives.” This reminds me of Stuart Hall’s notion of a “living archive of the diaspora”, about which he maintained “all three terms need to be considered for the hidden implications they carry” (Hall, 2001, p. 89).

“Len was always taking photographs”, Marie Garrison recalled as she began her contribution as the final speaker of the evening. She shared how her late husband never went anywhere without his camera, which was unusual in Black communities and family settings at the time, and he captured countless moments of everyday life, particularly of children who he noticed were very unrepresented in community and educational settings. We learned that Len started his professional photographic career in the 1960s as a medical photographer, documenting images of patients’ ailments for diagnostic purposes at the Royal Free and Maudsley hospitals in London, progressing to become head of the photographic unit at King’s College London Institute of Psychiatry. His work as a photographer was later developed through his postgraduate studies at University of Leicester, as well as his educational work at the Afro-Caribbean Education Resource Project (ACER) in Brixton, which culminated in showcasing his visual research on the Rastafarian movement and Black British youth at FESTAC – the Second World Black Festival of Arts and Culture in Nigeria in 1977.

Marie concluded her reflections on the value of Len’s photographic work by quoting the most photographed American man of the 19th Century, abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who like Len, harnessed the power of images to advance his cause, arguing: “what was once the special and exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now the privilege of all” and that Black people “can never have impartial portraits at the hands of white artists”.

Intergenerational Library Learning

During his reflections, Eddie Otchere cited Paolo Freire’s Pedagogy of The Oppressed, recalling how he had been schooled in the Black radical tradition from a young age by his history teachers who were friends of Len Garrison. This political education informed Eddie’s reflections on how the alumni portraits he is developing with Phillips for the Black at Sussex project is part of a wider and longer history of liberatory learning struggles and dialogues. Eddie also referred to the power of the 24-hour library available to all at Sussex, and the legacies of Black research and education embedded with it, which he argued is “what archives are here for”.

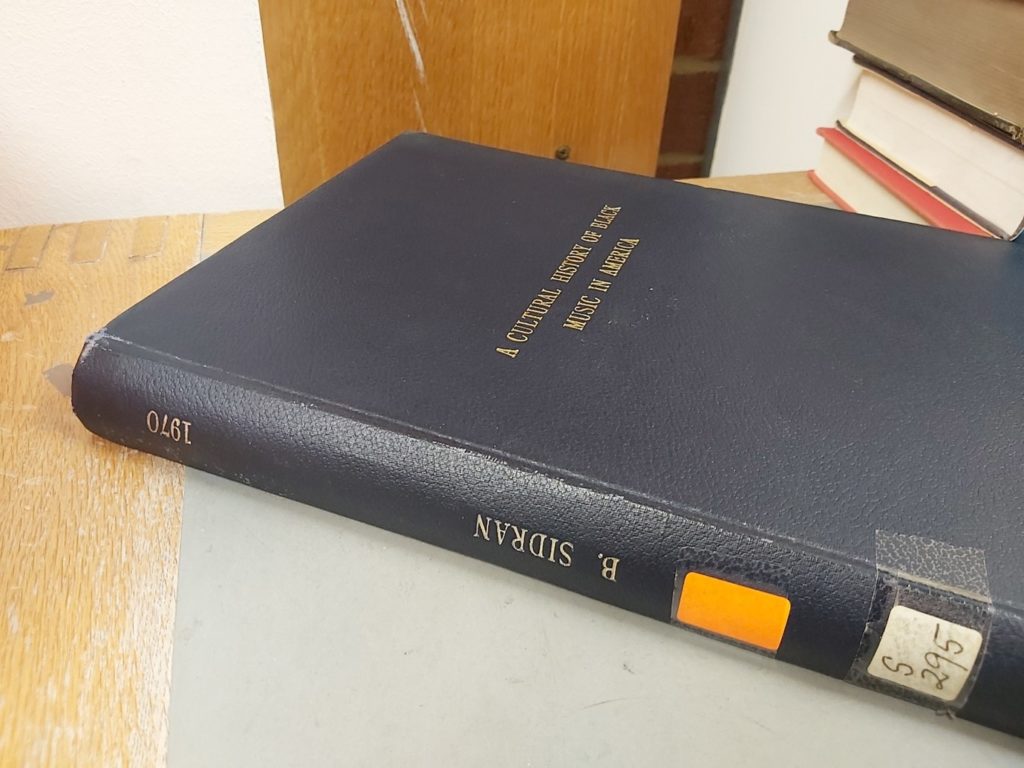

Professor Martin Evans shared the impetus behind his role developing the Black at Sussex programme, which was in part inspired by an interview he did with Professor Paul Gilroy in 2018. This interview informed Evans’ teaching on the current core module for History undergraduates at Sussex called History of Now, for which I have delivered anti-racist information literacy teaching. Gilroy is an award-winning sociologist and Professor of Humanities and Founding Director of the Sarah Parker Remond Centre for the study of Racism & Racialisation. He undertook his BA at Sussex between 1975 – 1978, and in conversation with Martin he reflected on the way in which he was able to discover the contributions of Black authors and scholars who had come before him through the collections available to him at the university Library. Gilroy recalled how as a young student at he “immersed himself” in the Rosey Pool Collection of twentieth century African-American cultural and political literature and letters available at the Library; as well as a key discovery of the Sussex PhD thesis by popular jazz musician Ben Sidran, titled “A Cultural History of Black Music in America: The Foundations and Functions of an Oral Culture” (1970) and was published as the book Black Talk in 1971.

I sat reading his PhD thesis in the library at Falmer and I thought – so this academic work!!!! – maybe I can take the things I know and render them in a compelling historical voice.

(Paul Gilroy, interview with Martin Evans, 2018)

Gilroy’s educational experience via the University of Sussex Library legacy of Black scholars who came before him informed Gilroy’s subsequent writing and publication of one of his most famous books, There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack. Martin shared how he had been discussing this with a PhD student from a Caribbean background who had felt very isolated at Sussex, who was amazed to find out from him that Paul Gilroy and been a student there in the late ‘70s, and shared that if she’d known earlier it would have made her time at Sussex more meaningful.

As current Sussex undergraduate student Valerie Kporye astutely remarked during the event, the value of the Black at Sussex project is the way in which intergenerational connections are created for meaningful open dialogue on what it means or has meant to be Black at Sussex, and the ways in which spaces of exclusion and inclusion are formed and re-formed through these processes of reflection. “As a student you’re quite limited what change you can make on the curriculum”, Valerie observed, but discovering the legacies of Black students who came before her, particularly through her exploration of the legacies of AFRAS in the university archives and via conversations with fellow Black alumni, has helped her to feel a sense of belonging and connection to radical open discourse that transcends the present moment.

Intergenerational learning was also a theme present in Jenny Mitchell’s contribution to the launch event. After a moving recital of her poem Black Men Should Wear Colour, dedicated to her brother, she reflected on her time as an undergraduate at Sussex. Jenny acknowledged what a difficult time she had as a student of English Literature, struggling to adapt to the culture shift of university life as a young adult from a strict family background, being overwhelmed by the “poshness” and the “whiteness” of Sussex campus life, as well as the emotional trauma of grieving her brother’s death at that time, for which she got no institutional support. In spite of this, gaining a Sussex degree opened doors for Jenny after graduating, and she has developed a successful career as an award-winning poet whose work explores the global legacies of British transatlantic enslavement, with the aim of opening up “conversation between people of all ‘races’ about this history” for collective accountability and healing.

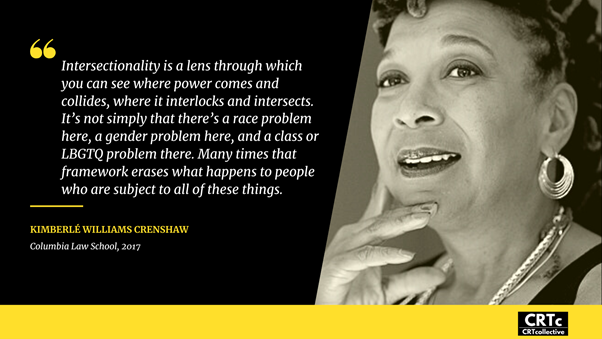

Jenny has also applied the healing power of literature to working with young people in library settings, including young care leavers considering university. Her work offers valuable insights for higher education widening participation programmes. Jenny reflected that universities need to acknowledge that being Black and from underprivileged backgrounds at university is a 24/7 experience, and hence there has to be so much care, support, investment, and resources given to each individual Black student, in order to place them on an even playing field. Jenny concluded her contributions by highlighting the need for the Black at Sussex programme to highlight the particular experiences and legacies of Black women alumni, a point which also chimed with Topher Campbell’s reflections on the need for an intersectional approach to the project.

From interdisciplinarity to intersectionality: “making difference work”

The founding vision of Sussex in the 1960s included the integration of public art with campus life. Evans referenced this when discussing the vision for the Black at Sussex programme, which brings together historians, world-class artists and curators, including the legendary photographers Charlie Phillips and Eddie Otchere, and curator Jenni Lewin Turner, and a range of university staff, students and community stakeholders, to create an inclusive visual and historical legacy for the intersectionally diverse communities of Sussex, which is integrated with the present and future cultural fabric of the university. The pedagogical foundations of Sussex as a university were designed to break the mould of traditional academic departmental silos through an interdisciplinary schools system, putting arts into dialogue with the sciences and African and Asian studies into dialogue with European studies. Founding Father Professor Asa Briggs dubbed this mission as forging “a new map of learning”.

Interdisciplinarity was apparent in the learning and creative journeys of the speakers at this event, with the artistic and literary careers of Michael McMillan, Topher Campbell, Jenny Mitchell and others having spanned a range of genres and mediums. As both Topher and Michael highlighted, however, what is important is the craft and the active doing of producing art and knowledge, rather than the notion of interdisciplinarity per se, which is a Eurocentric concept that is misplaced in an Afro-Caribbean-centred approach to cultural and knowledge production. McMillan referred to the Surinamese notion of Ala Kondre – unity through difference – to articulate this; and Campbell reflected on how – particularly as someone who came out as a Black Queer young person in the 1990s when homophobia was rife across all societal and racial groups (the violent effects of which he experienced at Sussex) – the notion of intersectionality is more resonant than interdisciplinarity.

Active intersectionality is relevant to archive-making as well as art-making, as evidenced in the rukus! Black, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Trans (BLGBT) Cultural Archive, which Topher X co-founded with his long-time collaborator Ajamu X, and which remains the largest Black-led LGBTQ+ archive in the world. This is housed at the London Metropolitan Archives rather than the BCA, since unfortunately at the time the archive was created, structural homophobia within Black and diasporic communities and cultural institutions posed significant barriers. Topher and Ajamu benefitted from the teachings of Stuart Hall in the development of their arts collective and archive, who offered them the phrase “making difference work” to articulate their boundary-crossing creative interventions, which have made huge cultural impacts in artistic and cultural heritage fields5 (The Homecoming: A Short Film about Ajamu, 1995; Ajamu X, Campbell and Stevens, 2009; Morris, 2022). In a recent Black Digital Archive podcast on The Oral Tradition, Ajamu X discusses the evolution of the rukus! Archive and makes the important point that

“we need to think that the archive is not static but the archive is in motion, the archive is constantly in process. Move away from the archive as a dead box for dead history, towards something more organic, more alive.”

(Ajamu X, 2021).

Archives (including digital ones) are material, embodied entities that are generated and created over years and carry with them vital affective forces which transmit knowledge and human connectivity and create intergenerational dialogue which can be harnessed for intersectional understanding and social change6. As Ajamu wisely continues, we do not engage enough with the archive as a tactile, living, embodied assemblage – we do not talk about this enough in archival discourse and practice “because we are locked into this social public framework about who we are and what we are”.

Ajamu’s words resonate in dialogue with those of the speakers present at the Black at Sussex launch event, and also reverberate in my encounters with the University of Sussex archive for my research fellowship. There is plenty of white space and white noise in this institutional archive, as the voices of people like Topher, Michael, Jenny, Valerie, and so many more Black alumni, are so seldom found in the boxes upon boxes of official institutional memory. This is a balance I intend to redress in my research and practice, by highlighting archival absences and racialised oversights in the making of university history and futures and inviting current and former marginalised Sussex students and staff to bring the archive to multidimensional life with their stories. A call for participation will soon be forthcoming.

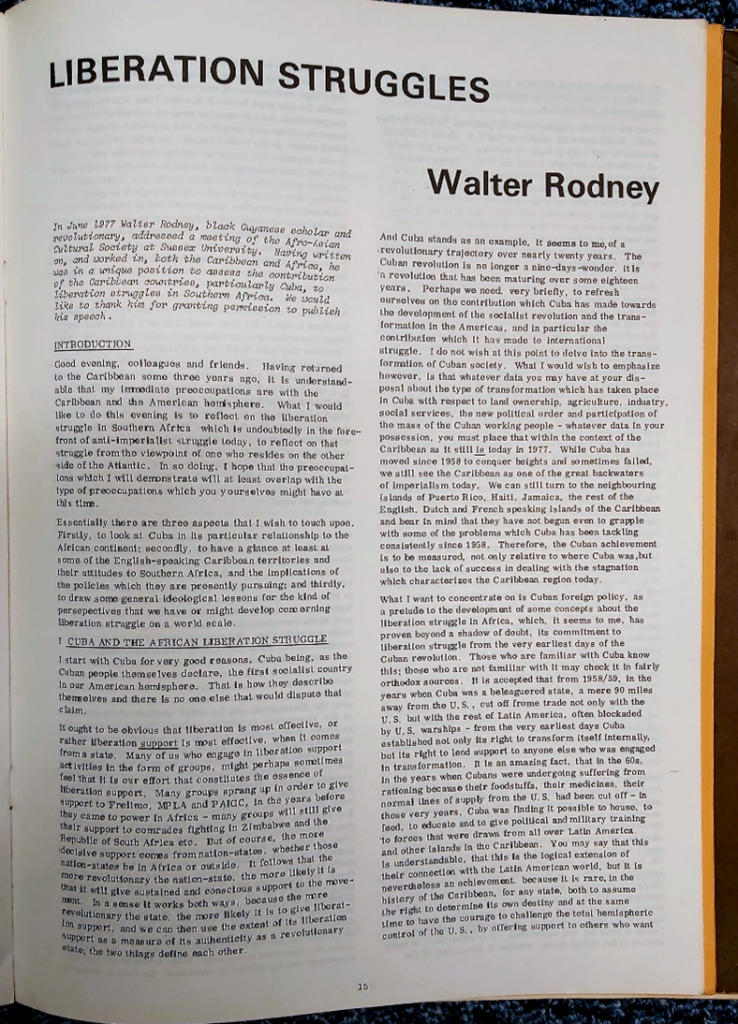

I aspire for this to be a form of “making difference work” that benefits those individuals and communities more than it does the white gaze and privilege of the institutional power structures (including my own whiteness) that dominate the university. In this sense, I am learning from the approach of the University of Repair, an antiracist initiative led by Esther Stanford Xosei in collaboration with the Decolonising the Archive collective, inspired by the “groundings” principles of Walter Rodney (1969).

Footnotes

- Print volumes of this journal are available at University of Sussex Library here.

- Coard’s work was more recently recognised in Steve McQueen’s Small Axe series on BBC and the BBC documentary Subnormal.

- Since publishing this article I have discovered that Valerie Kporye has written and published an inspiring and insightful article for the Royal Historical Society blog, which introduces the Black at Sussex programme with a focus on the photographic portraits of Sussex Black alumni by Charlie Philips and Eddie Otchere. Highly recommended reading.

- A copy of my present article as well as Valerie Kporye’s RHS blog has been digitally deposited in the University of Sussex Archive.

- Topher’s first film The Homecoming: A Short Film about Ajamu (1995), features Stuart Hall analysing Ajamu’s work. Available to watch via BFI Player. Congratulations to Topher for achieving the Pink News Broadcast of the Year Award for his brilliant 2022 documentary film Moments that Shaped Black Queer Britain. Listen to Ajamu X talking about the rukus! Archive and oral traditions here.

- In October this year I chaired a fascinating panel discussion featuring Topher Campbell alongside a diverse group of Black, Queer and Trans archival and library practitioners at The Coast is Queer literature festival, where these themes and more were discussed. Video recording available on request.

References

Ajamu X, Campbell, T. and Stevens, M. (2009) ‘Love and Lubrication in the Archives, or rukus!: A Black Queer Archive for the United Kingdom’, Archivaria, pp. 271–294. Available at: https://archivaria.ca/index.php/archivaria/article/view/13240

Black Digital Archiving (2021) The Oral Tradition podcast with Ajamu X. Available at: https://blackdigitalarchiving.netlify.app/ (Accessed: 5 December 2022).

Charlie Phillips – I Was Always Here (2022). London: Gramercy Park Studios. Available at: https://www.gramercyparkstudios.com/charlie-phillips-film (Accessed: 5 December 2022).

Crenshaw, K. (2017) Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, More than Two Decades Later. Columbia Law School. Available at: https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality-more-two-decades-later (Accessed: 5 December 2022).

Field, P., Bruce, R. and Hassan, L. (eds) (2019) Here to stay, here to fight: a race today anthology. London: Pluto Press.

Hall, S. (2001) ‘Constituting an archive’, Third Text, 15(54), pp. 89–92. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09528820108576903.

Kporye, V. (2022) ‘Black at Sussex | Historical Transactions’, Historical Transactions, 26 November. Available at: https://blog.royalhistsoc.org/2022/11/26/black-at-sussex/ (Accessed: 9 December 2022).

Johnson, L.K. (1984) Making History [LP]. Studio 80, London: Island Records Inc.

Morris, N. (2022) ‘Moments that shaped queer Black Britain’, Metro, 14 June. Available at: https://metro.co.uk/2022/06/14/moments-that-shaped-queer-black-britain-16825185/ (Accessed: 5 December 2022).

Rodney, W. (1969) The groundings with my brothers. London: Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications.

Sidran, B. (1970) A cultural history of black music in America: the foundations and functions of an oral culture. University of Sussex.

The Homecoming: A Short Film about Ajamu (1995). Available at: https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-the-homecoming-a-short-film-about-ajamu-1995-online (Accessed: 5 December 2022).

Leave a Reply