Introduction

In my first blog post I introduced the Centre for Multi-Racial Studies (CMRS), which was established at Sussex in 1964 and ran until 1974, with its main site in Barbados in partnership with the University of the West Indies. The discovery of this forgotten centre via newly acquired archival collections at The Keep has occupied a large portion of my interest and time during my fellowship, growing my knowledge of Sussex’s hidden histories of postcolonial knowledge formations, which I aim to bring to light. This blog post details the history and legacy of the CMRS and raises questions about racialised archival silence and noise, to make the case for bridging library, archival, scholarly and community approaches to reparative history and epistemic justice.

Archival avenues

I first became aware of the history of the CMRS when, close to the start of my AHRC-RLUK fellowship in October 2022, I was exploring the University of Sussex Collection at The Keep, which is organised by institutional function according to these five sections : Governance, Staff and Faculty, Research, Teaching and Assessment, and Students[1].

I began my archival catalogue search across this collection with a range of grammatically related keywords to help me identify aspects of knowledge organisation and institutional memory relating to notions of race, colonialism, imperialism, national and cultural identity. In this way, I found three CMRS annual reports in the ‘Research Centres’ section of the archival hierarchy. This subsequently led me to the administrative papers of John Fulton, a subseries within the ‘Sussex House Admin’ series of the Governance section. These papers, (spanning 1960-1967, the years of Fulton’s tenure as founding Vice Chancellor), charted the origins and development of the CMRS, including correspondence with ministers in the Foreign Office and diplomats from various countries, applications for funding from a wide range of international corporations, and correspondence with Fernando Henriques. I could see there was an important story here, but not enough information.

I discussed this puzzle with Sussex Archivist Karen Watson, who a few weeks later happened to be called to Sussex House (the university’s administrative centre), to examine several boxes of historic files that were earmarked for disposal. Among other items of value, she noticed several piles of material relating to the CMRS and brought these to my attention. Over the past few months I have been working though these uncatalogued archives which tell a rich but partial story of the CMRS’s development, mainly from the point of view of Asa Briggs, who helped to champion the centre through troubled waters over its decade-long establishment.

I began this section by outlining the structure of my way in to these archival avenues, in order to highlight the significance of the core archival science principal of provenance, which traditionally denotes the causal relationship between records and the individuals, groups or organisations who created them for particular functions, and hence requires these records to be held together and sequenced according to their original order. Until the recent critical turn in information and archival sciences, there has been scant attention to the cultural and political dimensions of this principle, which can be theorised as ‘societal provenance’[i]. Records that are archived by organisations are highly affected and infused by the society and culture in which they are created, and archivists are not immune to the biases and inequalities that permeate such informational contexts when they accession, preserve, and maintain these records[ii]. This notion of societal provenance is, I argue, crucial for understanding the ways in which racialised archival biases and silences develop.

CMRS origins and mission

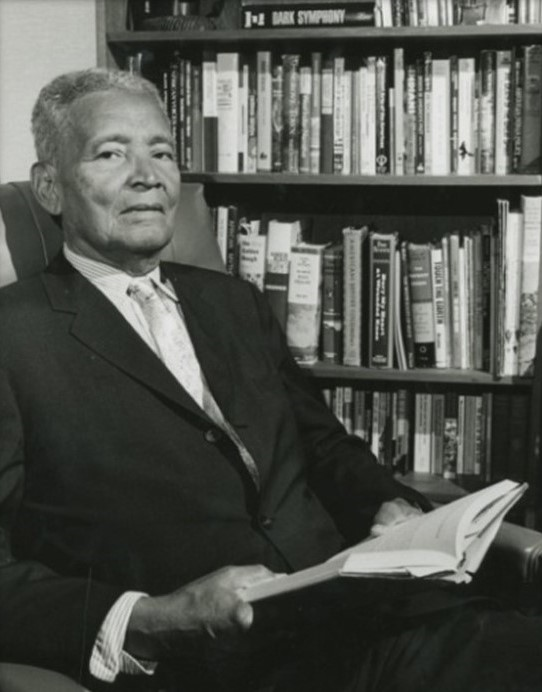

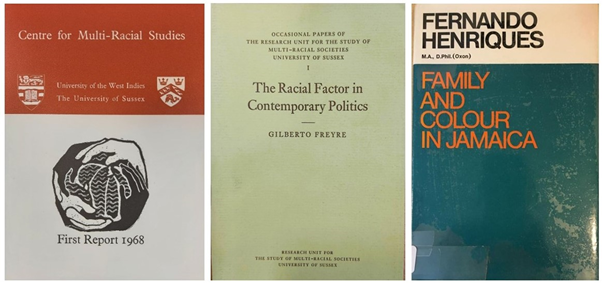

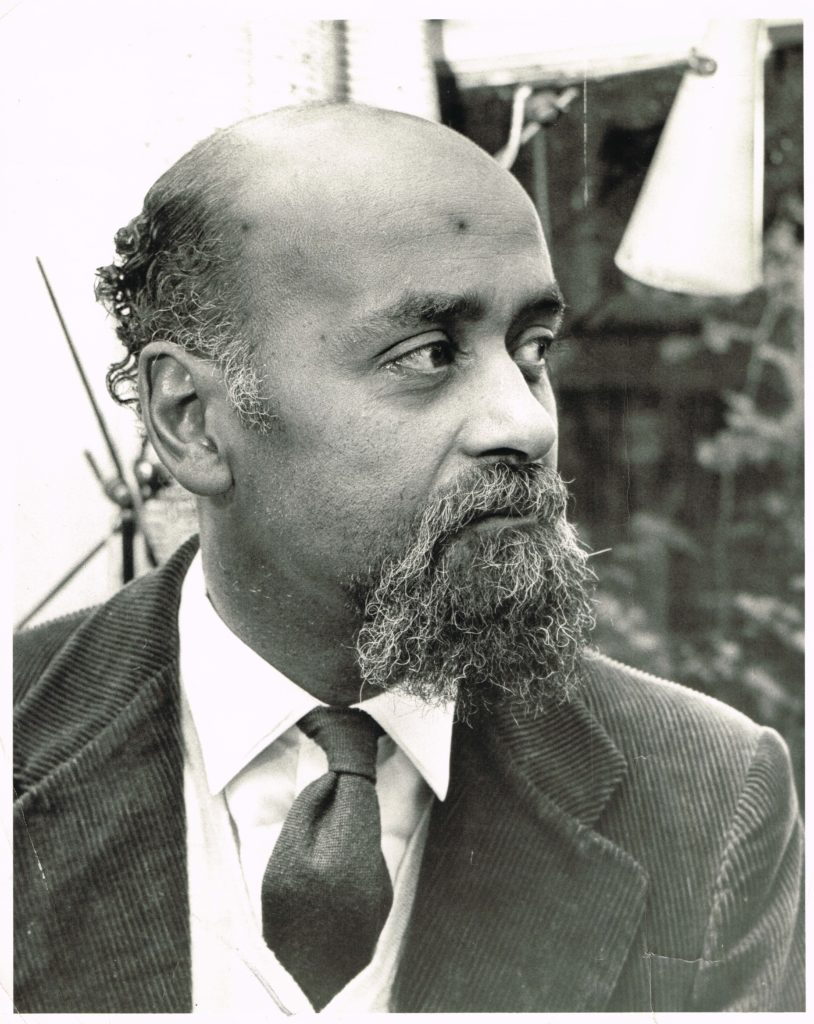

In 1964, the same year the University of Sussex Library opened, and the School of African and Asian Studies commenced, The CMRS unit was established within the School of Social Studies. Funded principally through a grant from the Bata (“Shoemaker to the world”) Foundation, with support from the UK Foreign Office, CMRS was officially inaugurated at Sussex by Brazilian sociologist Dr Gilberto Freyre in June 1965. The Director of CMRS was Professor Fernando Henriques, recruited to lead this project by Asa Briggs, who knew him from their time together at University of Leeds, where Briggs was previously Professor of Modern History, and Henriques a senior faculty member in Social Anthropology. I will return to the significance of Henriques’ life and work for the intellectual history of Sussex, and Black British and Caribbean history more broadly, towards the end of this blog post.

In the 27th October 1964 edition of the University of Sussex Bulletin, the CMRS was announced as having three main tasks:

- the assembly of materials and information relating to race relations with particular reference to the Caribbean Area, Latin America and Africa;

- research projects relating to this field in which graduate students would be involved;

- the arrangement of seminars of varying duration for people outside the University and particularly from the areas concerned. The members of these seminars would be drawn from the universities, the public services, business and labour.

The first two priorities relied primarily on development of a specialist library to serve as a knowledge base for progressive research on “the race factor” in global politics and culture. While Caribbean, Latin American, and African contexts were the main geographic focus, the Centre’s outputs were not limited to these regions; British, European, and North American comparative studies of race and class were also developed. The third priority aligned with concerns of government and corporations alike about tensions around race relations in a rapidly diversifying citizenry and labour market in a post-imperial Commonwealth context.

Universities, especially new ones like Sussex, had a role to play in these addressing these issues. Founding VC John Fulton proclaimed in the opening lines of his inaugural address, published in The Times on 16th August 1961:

Throughout the world – and especially in the underdeveloped countries – education is the new religion. Men of every colour, race and creed see in it the key that will open the doors to self-realization for the individual, to the true independence of nation or group, to the possibility of co-existence in peace for a divided human race; and, above all, to influence over the intellectual leaders of the generations to come.

Fulton, J. S., ‘Balliol By The Sea Faces Its Future’, The Times, 16 August 1961, p. 9.

In a like-minded vein, Fulton’s collaborator Asa Briggs’ mission to “as he put it, ‘redraw the map of learning’ at Sussex made sense: it was designed not simply to guide Britain’s path into the future but to balance the redrawn map of geopolitics”[iii].

Building the CMRS knowledge base from Falmer to Barbados

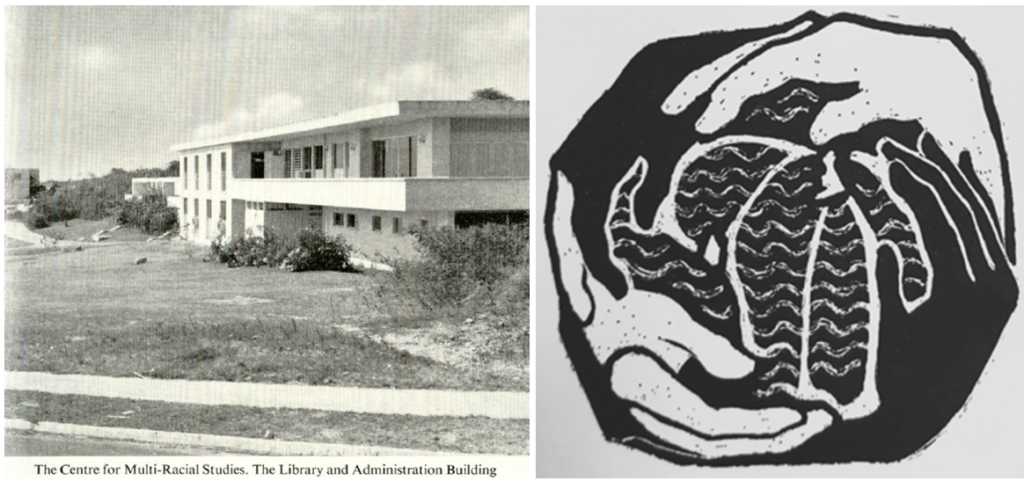

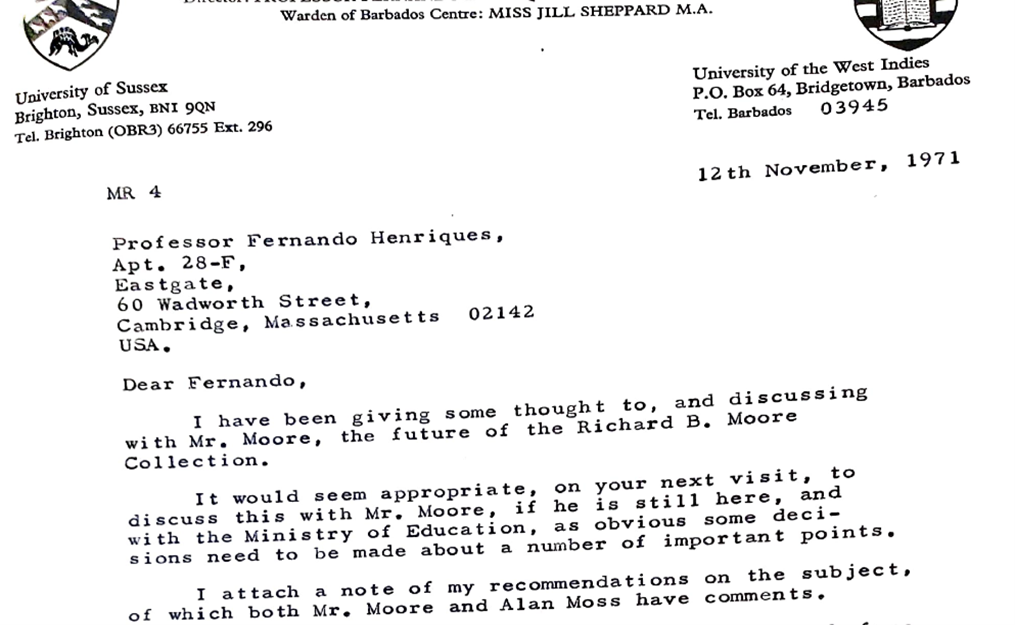

With political and financial backing from the Ministry of Overseas Development, in 1965 Sussex developed a partnership with The University of the West Indies (UWI) to develop a CMRS research centre at the Cave Hill campus in Barbados, with land provided by the island’s Prime Minister. The CMRS building was the property of the University of the West Indies and staffed by employees of Sussex, with Professor Henriques serving as Director, supported by a secretary, research assistants, and resident warden, Jill Sheppard.

The CMRS opening ceremony in the new building took place on 15th and 16th April 1968, in the lecture hall that Asa Briggs announced in his inaugural speech would be named “The Martin Luther King Hall”, in memory of his legacy following his assassination just eleven days prior, making the priorities of the centre even more urgent [iv]. Other distinguished speakers at the two-day opening ceremony included The Prime Minister of Barbados, Errol Barrow; Vice Chancellor of the University of the West Indies, Sir Philip Sherlock; Pro-Chancellor of the University of the West Indies and Prime Minister of Trinidad and Tobago, Eric Williams; Lord Caradon, Permanent U.K. Representative at the United Nations; the Governor-General of Barbados, Sir Winston Scott; and Professor of Anthropology at the University of Cambridge, Meyer Fortes (Henriques’ former doctoral supervisor, a white South African-born scholar of West African cultures). Fortes argued for the urgent need to apply a new generation of research and practice to the “spectre of race” haunting not only Europe (referencing the opening words of Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto, although not in the same ideological spirit), but “haunting the whole world”[v]. I will come back to this notion of haunting via a decolonial archival perspective in the conclusion of this article.

In his opening speech, Professor Eric Williams argued that the universities of “the Commonwealth Caribbean territories … can never afford to adopt a position of ivory tower detachment”.

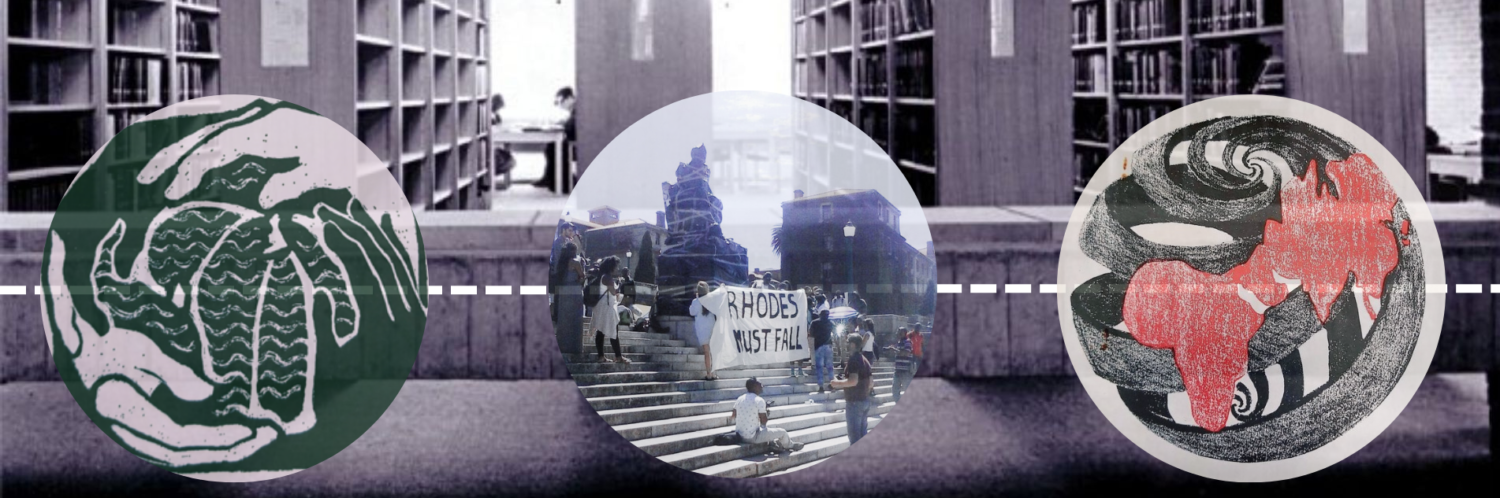

The centre’s logo was designed by Rosamund Seymour, Fernando Henriques’ wife, who also did a lot of work developing the centre. The linocut print depicts black and white hands in a circular formation cradling the islands of Britan and the West Indies between an abstraction of the Atlantic Ocean. This design adorns the annual reports and official publications of the centre, which became part of its nascent library collection.

Libraries of Racial Discovery

The Barbados site was also the site of one of the CMRS’s greatest assets, the specialist research library, whose bookshelves were built from wood gifted by the Guyanese government and filled with the books and documents of its founders and associates, as well as the Richard B. Moore Collection. This unique and rare collection was purchased by the Barbados Lions’ Club and presented to the Government as an Independence gift, and subsequently housed at the CMRS.

Richard Benjamin Moore was a Barbadian author, lecturer, political activist, and book dealer, who divided his life between Barbados and Harlem (New York City), where he experienced and raised consciousness about “the realities of European colonialism in Africa and the Caribbean, as well as the injustices of Jim Crow and lynching in the American South”[vi].

Over the span of half a century, Moore amassed a personal library of over fifteen thousand books and pamphlets, many of which were rare or out of print, documenting the lives and achievements of African and diasporic communities. As Burghardt Turner asserts: “This was one of the most extensive and complete searches for such literature ever to be undertaken by an individual without government, foundation or organization financial support and with no appreciable personal wealth or income to support the effort.”[vii] His motivations for developing this collection were to demonstrate ample evidence of the pernicious falsity of white superiority, and to address the gap in most libraries between the history and culture of African, Afro-Caribbean and Afro-American communities.[viii] In this way, his work can be understood as enacting and articulating a theory of historical recovery, which Adalaine Holton and Hannah Ishmael analyse through the work of Arthur Schomburg’s archiving and publicising of diasporic Black culture for Pan-African liberatory ends [ix].

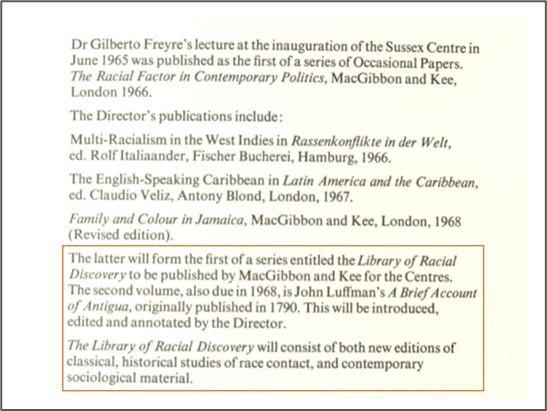

This collection was hence a prized cornerstone of the bibliographic and intellectual foundations of the CMRS, which Professor Fernando Henriques intended to develop into a ‘Library of Racial Discovery’, via a series by his own publisher MacGibbon and Key, with the first title being his Family and Colour in Jamaica (1953, with the second edition hot off the press in 1968). This book is a significant work of historical anthropology which analyses the enduring impact of European colonialism and slavery on multi-racial Jamaican society via variegated class-colour oppressive hierarchies.

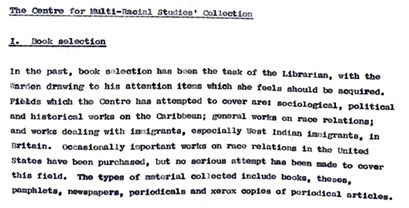

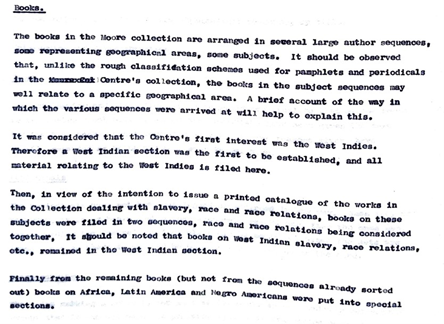

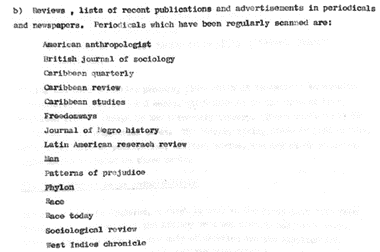

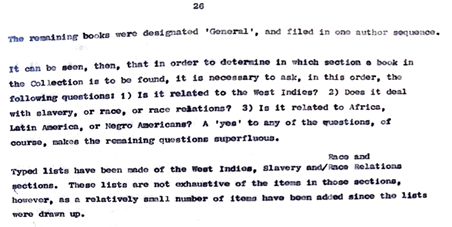

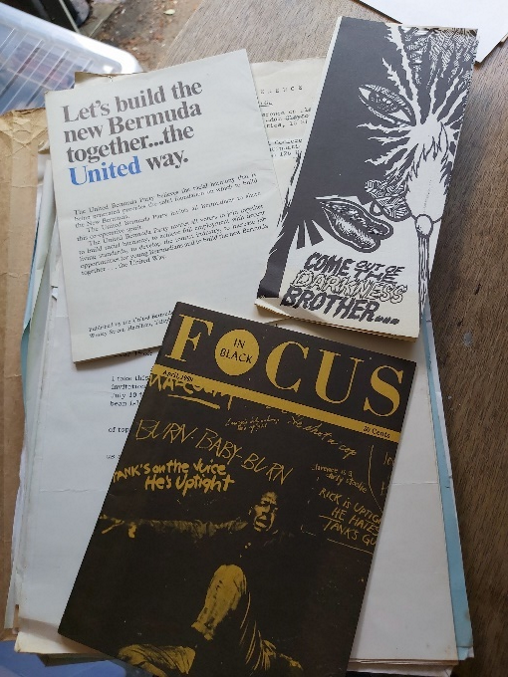

The book stock of the CMRS Library was divided into two sections: the Richard B. Moore Collection comprising one half, and materials acquired by the Centre on the other, the latter distinguished by a CMRS book stamp and differently shaded cards in the catalogue. As well as books, the library acquired a variety of periodicals, pamphlets, government publications, press cuttings and tape recordings. The cataloguing was done in a modified form of the 1967 Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, cross-referencing authors’ works with other relevant authority files.

Records show how difficult it was to develop and sustain funding for the Centre’s research programmes and its library, despite the high esteem in which it was held.

Thankfully, the Richard B. Moore Collection is preserved and available at the Sidney Martin Library at University of the West Indies Cave Hill campus, and is listed on the Barbados National Register of UNESCO’s Memory of the World Program. I am in the fortunate position to travel to be able to travel Barbados to explore this and related collection when I commence my Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship (2023-2026, School of Global Studies, University of Sussex), which will expand the current project to examine transnational postcolonial library legacies and social movements connecting Sussex with knowledge spaces in the Caribbean and South Africa (watch this space for further blog posts detailing this).

The remainder of the present article will introduce the hitherto hidden history of Fernando Henriques, which is now ripe for renewed recognition, since my research – which I’d like to think is continuing his vision of a ‘Library of Racial Discovery’ – has led to his personal archive being donated to the University of Sussex special collections at The Keep, thanks to his son Professor Julian Henriques[2]. The above images of the notes on the CMRS Library are taken from this personal archive (as yet uncatalogued).

Re-collecting and rediscovering Fernando Henriques

Fernando Henriques (1916 – 1976) was born in Jamaica and moved with his whole family to England at the age of three in 1919. He served in the National Fire Service in London during the Second World War[3], and soon after won a scholarship to study History at University of Oxford, where he became the President of the Oxford Union in 1946, and in 1948 completed his anthropology doctorate under the supervision of Meyer Fortes and Alfred Radcliffe-Brown. He was then appointed as Lecturer in Social Anthropology at University of Leeds in 1948 and went on to become “Dean of the Faculty of Economic and Social Studies – possibly the first Black academic to hold such a role anywhere in the UK”. This unprecedented trend continued when he was recruited to Sussex by Briggs in 1964, becoming the university’s first Black professor.

In a ‘Personal Statement’ chapter of a collective memoir of the Henriques family[4], Fernando reflects on his diverse ethnic and cultural heritage as a man racialised as Black in colourist Caribbean and racist British contexts. Fernando also reflects in this chapter on how his employment at Sussex in 1964 to direct the CMRS necessarily required a personal as well as an academic involvement:

“In some occupations the individual can preserve a distance: the lawyer does not become involved with the personal lives of his clients. But my suggestion is that race relations does demand a personal commitment from those who choose this as their field. My criticism of many white people, in both Britain and the United States, who have elected to embark on this course is that they lack feeling for the problems which exist, and merely regard it as another career. In some cases in the field of black/white relations the whites involved do not really care about black people as persons but as part of an equation which must be understood in objective terms. It requires great imagination on the part of white people to enter fully into the experience of what it means to be black in a white world.”[x]

As a white British person engaged in the historical-sociological study of race relations and coloniality in a professional academic library and archival context, I heed this provocation acutely. The professional, like the personal, is political [xi]. The UK information profession is 95% White, with only 0.8% of the surveyed workforce identifying as Black[xii]. I am committed to an ongoing process of critical self-reflexivity and anti-racist praxis in my work as a member of this white professional supermajority, following Mario Ramirez’s call for a liberatory critique of archival “whiteness and its semantic markers (such as tradition, neutrality, and objectivity) and having honest dialogues about how we as a profession and individuals perpetuate inequality”[xiii]. As an interdisciplinary scholar I strive to apply what Martin Savransky calls “decolonial sociological imagination” to my work, which cultivates a recognition that “there is no social and cognitive justice [and I would explicitly add racial justice here] without existential justice, no politics of knowledge without a politics of reality”[xiv].

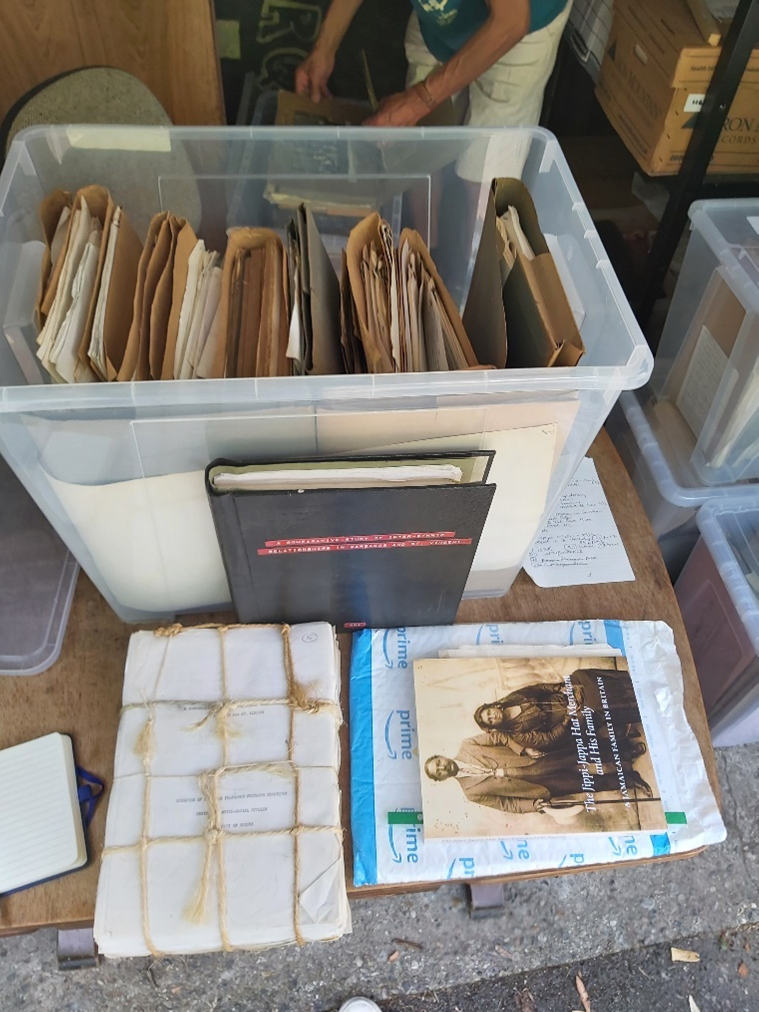

My experience of exploring the archives of the CMRS at The Keep contrasted with my encounter with his personal archive at the Henriques family home. I met Julian Henriques at a garage outside his daughter’s flat in North London. He had laid out a table ready for me to delve into the five large crates of papers and ephemera documenting his father’s life and work, covering around half a century of material, including anthropological research on race relations whilst at Oxford in the 1940s, Leeds in the 1950s, and Sussex and the West Indies in the ‘60s and 70s’. Quite unlike the institutional archival environment of the Keep, with its warehouse white walls, fluorescent lighting, and clinically-cool atmosphere; being greeted with a warm handshake at the intimate space of the family garage filled with the materiality of living memories, and leafing through the files to the sound of summer birdsong and sights of Henriques family members smilingly passing by, reoriented my senses to past and present lives and knowledges in vivid colour. In this sense, we were re-collecting this collection via its familial and societal provenance and roots.

Conclusion: listening to archival noise

As Sara Ahmed attests, “Whiteness could be described as an ongoing and unfinished history, which orientates bodies in specific directions, affecting how they ‘take up’ space.”[xv] The archival bodies of knowledge of CMRS and Fernando Henriques has thus far taken up only a marginalised, silenced and forgotten space in the institutional memory of the University of Sussex. Indeed, the redundant files that were being discarded from Sussex House could have quite easily ended up being disposed of, were it not for the efforts of a single archivist in dialogue with a research fellow interested in the (post)colonial and racialised lives and legacies of the library and archive. The gift of the Henriques’ personal archive will form its own archival special collection at the University of Sussex, thereby complementing and contextualising the existing CMRS institutional records in its own right. There is hence now the potential to recover the societal provenance of these records and make audible the voices within them.

Stanley H. Griffin defines decolonising archives as a necessarily noisy activity, disrupting Eurocentric epistemic silences and violences with the rich diversity of Caribbean culture via polyvocal and multimodal archival forms[xvi]. He likens institutional archives to the lifeblood of an institution, and in the many institutional contexts wherein much blood has been spilled through the violence of colonialism, we need to listen to how this blood beats through the rhythms of the records: “the repressed and silenced in the archival records will agitate and haunt until full recognition and acknowledgement of its informational and enduring values are secured. These noises demand the attention of both archivist and researcher alike.” [xvii]

In my work this attention involves tuning out (like a radio) what I call white noise in the archive: the dissonant interference of the whiteness of institutional machinery and memory in constructing what and how we re-member and recover diverse knowledges. For archivists and librarians this needs to involve reparative archival description to make archival access points more inclusive, as well as pro-active collecting policies that imaginatively attend to unequal frequencies and channels of diverse voices[xviii]. Together with scholars working across the humanities and social sciences, we need to heed the calls of both Stuart and Catherine Hall to expose and repair the ways in which imperialism continues to structure and fracture our institutions, records and cultural heritage[xix]. Both archivists and scholars need to come together to approach this work dialogically, contextualising archival sources within their societal provenance; recognising archives as sites of cultural contestation and political struggle, and activating them according to reparative archival principles of recovery and transformation. Our archives need to be living organisms, animated and articulated in sonic technicolour, pitched to the ears and eyes of diverse publics.

Endnotes and References

[1] The Library’s administrative archives sit within the ‘Services’ series of the Governance section.

[2] Thanks also go to Professor Jeremy MacClancy, who consulted the CMRS archives at The Keep for his research on Fernando Henriques’ contribution to anthropology, and connected me to Julian Henriques.

[3] He had wanted to serve in the RAF but was refused entry after a sergeant told him that “wogs … were not considered officer material”, on which he reflects was the ongoing stronghold of the “shibboleth” of British imperial power (Holland 2020, pp.166-167).

[4] This memoir, The Jippi-Jappa Hat Merchant and His Family (first published in 2014), was written and published almost forty years after Fernando’s untimely death in 1976. The ‘Personal Statement’ chapter is the text of the intended introduction to his final monograph Children of Caliban: Miscegenation (1976), the published introduction of which was edited to be considerably shorter. The essay speaks volumes about Fernando’s lived experience and intellectual reflections on the intersectional societal nuances of race, class, and gender in mid-late twentieth British and Jamaican cultural and academic life.

[i] Michael Piggott, Archives and Societal Provenance Australian Essays (Oxford, UK: Chandos Pub., 2012).

[ii] Tom Nesmith, ‘The Concept of Societal Provenance and Records of Nineteenth-Century Aboriginal-European Relations in Western Canada: Implications for Archival Theory and Practice’, Archival Science, 6.3–4 (2006), 351–60; Anthony W. Dunbar, ‘Introducing Critical Race Theory to Archival Discourse: Getting the Conversation Started’, Archival Science, 6.1 (2006), 109; Anthony W. Dunbar, ‘Every Information Context Is a CRiTical Race Information Theory Opportunity: Informatic Considerations for the Information Industrial Complex’, Digital Transformation and Society (2023).

[iii] Matthew Cragoe, ‘Asa Briggs and the University of Sussex, 1961–1976’, in The Age of Asa: Lord Briggs, Public Life and History in Britain since 1945, ed. by Miles Taylor (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2015), pp. 225–47 (p. 226).

[iv] University of the West Indies and University of Sussex, ‘Transcript of Centre for Multi-Racial Studies Inauguration Ceremonies 15th and 16th April’ (Cave Hill Campus, Barbados, 1968). <https://uwispace.sta.uwi.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/2139/9297/DH-1Bc.pdf>. With thanks to Julian Henriques for finding this document in the UWI digital repository, which he cited in his chapter in Holland (2020).

[v] Julian Henriques, in Mark Holland, The Jippi – Jappa Hat Merchant and His Family, Second Edition (Horsgate, 2020), p. 216; University of the West Indies and University of Sussex, p. 15.

[vi] W. Burghardt Turner, ‘The Richard B. Moore Collection and Its Collector’, Caribbean Studies, 15.1 (1975), 135–45.

[vii] Turner.

[viii] Carolyn, ‘Richard B. Moore, The Caribbean Militant Of Harlem 1893–1978’, Harlem World Magazine, 2014 <https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com/richard-b-moore-caribbean-miltant-harlem/> [accessed 18 July 2023].

[ix] Adalaine Holton, ‘Decolonizing History: Arthur Schomburg’s Afrodiasporic Archive’, The Journal of African American History, 92.2 (2007), 218–38; Hannah J. M. Ishmael, ‘Reclaiming History: Arthur Schomburg’, Archives and Manuscripts, 46.3 (2018), 269–88.

[x] Mark Holland, The Jippi – Jappa Hat Merchant and His Family, Second Edition (Horsgate, 2020), pp. 188–89.

[xi] Shiraz Durrani and Elizabeth Smallwood, ‘The Professional Is Political: Redefining the Social Role of Public Libraries’, in Questioning Library Neutrality: Essays from Progressive Librarian, ed. by Alison Lewis (Library Juice Press, LLC, 2014), pp. 119–40.

[xii] Martin Reddington, A Study of the UK’s Information Workforce 2023: Mapping the Library, Archives, Records, Information Management and Knowledge Management and Related Professions in the United Kingdom & Ireland., 2023 <https://www.cilip.org.uk/?page=Workforcemapping> [accessed 21 July 2023].

[xiii] Mario H. Ramirez, ‘Being Assumed Not to Be: A Critique of Whiteness as an Archival Imperative’, The American Archivist, 78.2 (2015), 339–56 (p. 352).

[xiv] Martin Savransky, ‘A Decolonial Imagination: Sociology, Anthropology and the Politics of Reality’, Sociology, 51.1 (2017), 11–26 (p. 13).

[xv] Sara Ahmed, ‘A Phenomenology of Whiteness’, Feminist Theory, 8.2 (2007), 149–68 (p. 150).

[xvi] Vance Woods, ‘“There Is a Tangible Tension between What Is Held in Caribbean Archives and What Is Remembered in Caribbean Communities”: Interview with Stanley H. Griffin, of the University of the West Indies (Pt. 1)’, Archivoz, 2023 <https://www.archivozmagazine.org/en/interview-with-stanley-h-griffin-pt-1/> [accessed 19 July 2023].

[xvii] Stanley H. Griffin, ‘Noises in the Archives: Acknowledging the Present yet Silenced Presence in Caribbean Archival Memory’, in Archival Silences (Routledge, 2021), p. 85.

[xviii] Christina Kamposiori, Developing Inclusive Collections: Understanding Current Practices and Needs of RLUK Research Libraries (Zenodo, 13 July 2023) <https://doi.org/10.5281/ZENODO.8143097>.

[xix] Stuart Hall, ‘Whose Heritage? Un-Settling ‘The Heritage’, Re-Imagining the Post-Nation’, in Whose Heritage? (Routledge, 2023) (1999); Catherine Hall, ‘Doing Reparatory History: Bringing “Race” and Slavery Home’, Race & Class, 60.1 (2018), 3–21.

Such a wonderful and inspiring piece of work Dr. Corble! In your hands, hidden archival data dare to break their silence, being speaking slowly, first a but shy, with murmurs and whispers, and then more confidently, culminating in a crescendo exploding and taking revenge from past memories of oppression for those whose records could not even reach out the library in the first place because they were never worth registering for the rulers.

In my ethnographic research i encountered several times the question of whose life is worth living and whose life is worth a dignified burial – for people i worked with were considered non humans when they did not fit the norms. We can think about the archives in similar terms, what was worth being archived and what was not. You bring back to life things which were not officially recognised yet catalogued in unusual ways, giving their dignity back.

Your language is so beautiful too. I felt so moved by the last sentence: “Our archives need to be living organisms, animated and articulated in sonic technicolour, pitched to the ears and eyes of diverse publics.” In one sentence one can hear the voice and breath of the scholars who influenced you (Noisy activity) but also your own distinct voice – how you advance their thought (expanding the metaphor or noise into sonic technocolour), we can hear the voice and cross fertilisations with activists and colleagues at Sussex (sonic intimacy by Dear Malcolm James), we can hear the voice and breathe of the connection between life sciences and humanities which is a heritage of Sussex you like uncovering (archives as biological living organisms).

Congratulations for this piece, I look forward to reading more the Decolonial archival adventures on many islands from Alice in the Wonderland.

All the Best,

Demet

Thank you so much for this beautiful feedback Dr Dinler! I love discussing the life of the mind with you – conversations about knowledge-making and community-building are an important part of my living archival adventures!