At the end of April I’m going to be presenting at the History After Hobsbawm Conference as part of a panel on Marxist and post-Marxist social history. Fittingly, I will be presenting a collaborative collective project on protest Political Protest and the Police: Young People in Brighton that I produced with Tom Akehurst and Louise Purbrick. We produced the report in response to what we had witnessed at the demonstrations in defence of further and higher education in 2011. There are clear echoes around debates about policing and protest in the 1980s and in more recent years. But there are also some methodological implications about what it means to record a movement from within, (or from very very close to the edge at least). One of the key issues raised by the protest project for me as an activist academic was to explore how traditional socialist history could fit in what seems to be a political world beyond the organised Left? What are the lines of difference and development between activist historians now, and the forefathers of radical history? So much of the contemporary history project has been informed by earlier generations of Marxist academics who worked through the political possibilities of academic engagement with the traditional organised working class. But politically engaged contemporary history today also embraces the complexity of taking individual identities, personal experience and testimony seriously, that might be more of a fit with present day forms of resistance around Occupy and lifestyle politics.

Working up to preparing for the conference (the other side of marking) whilst marking this term’s research proposals for 1984: Thatcher’s Britain made me wonder if I could pin down Hobsbawm’s contribution to Observing the 80s.

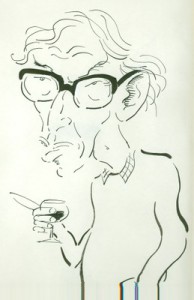

Eric Hobsbawm’s article ‘Falklands Fallout’ published in Marxism Today in January 1983 is one of the sources that was explicitly critical of the Falklands War at the time.

In Falklands Fallout Hobsbawm argues that the Falklands had been talked about more than any other recent issue, demonstrating that more people had ‘lost their marbles’ over the war than over anything else. In the absence of many personal lived connections between people on the mainland UK and the Falklands, people were incorporating the islands into their own narratives and concerns; around the nation, around memory and around the Left. One of the benefits of combining the different types of evidence in Observing the 80s is that we get to bring together lots of different types of talking about the war, that move between public discourse and personal exerience and engage with the cracks around mainstream political debate, so alongside Diana Gould and Tam Dalyell’s challenges to the legality of the sinking of the Belgrano, students explore the role of anarcho-punk as a form of anti war discourse, and of the use of the conflict by activist groups like the Socialist Society, Revolutionary Communist Party to create poles of debate, at least between each other. The life history evidence suggests more negotiated positions on the war, relatives of combatants challenge the price paid for the victory and the failures of the public to comprehend the importance of commemoration of the fallen, whilst maintaining the importance of military defence of the islands. Combatants themselves are critical of the politicians’ role in the war, and to some extent of the command decisions and power hierarchies, particular over equipment and communication. Whereas MOP respondents outlined different layers of analysis and evaluation. Some doubted the necessity and financial cost of maintaining the islands, others outlined the emotional politics of war describing feelings of ‘helplessness and incomprehension.’

For Hobsbawm, these narratives of past and present, however contradictory, in the form of ‘patriotism and jingoism’ could be used in Thatcher’s favour. The Observing the 80s collection suggests that experiences also encouraged people to question that narrative too.

Here is some more information about the conference

A major international conference, with plenary speakers and large parallel sessions, exploring where the study of history is heading and what it means to be an historian in the twenty-first century. Keynote speakers will include Mark Mazower (Columbia), Catherine Hall (UCL), Gareth Stedman Jones (Queen Mary), Chris Wickham (Oxford), Maxine Berg (Warwick), Rana Mitter (Oxford) and Geoff Eley (Michigan). The conference is organised by Birkbeck, University of London, where Eric Hobsbawm taught most of his life, and by Past & Present, which he co-founded. It will be held with the support and assistance of the Institute of Historical Research, University of London, and the Birkbeck Institute of the Humanities.

As Dr Brodie Waddell one of the conference organisers explained on her blog:

“It’s going to be quite an occasion – I don’t think I’ve ever seen so many big-name ‘Munros’ from the world of history on a single programme. Although the event will partly be a celebration of Hobsbawm’s legacy, it also promises to be a forum for leading historians to tackle big issues such as nationalism, protest, class, environment, and so on. I won’t attempt to list all the speakers except to say that I’m particularly looking forward to the panels on ‘the crisis of the 17th century’ (Sanjay Subrahmanyam, Geoffrey Parker, John Elliott), on ‘Marxist and post-Marxist social history’ (Andy Wood, Jane Whittle, Lucy Robinson), and on ‘Frameworks of historical explanation’ (Peter Burke, Joanna Innes, Renaud Morieux).”

The hashtag for the conference is #afterhobsbawm.

To register, visit https://www2.bbk.ac.uk/history/hobsbawm.

Trackbacks

[…] By Dr. Lucy Robinson, Senior Lecturer in History at the University of Sussex. This post was first published on Observing the 80s. […]