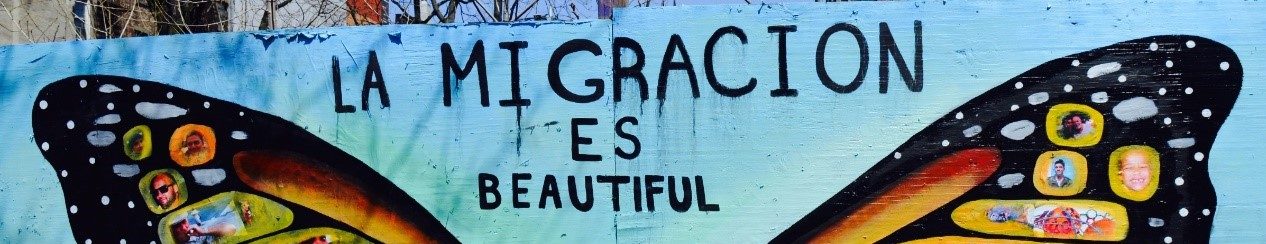

![Bole Michael, Addis Ababa. Credit: Jasmine Halki [original]; Licensed under CC BY 2.0](https://www.displacementeconomies.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Bole-Michael-Addis-Ababa.jpg)

By Adamnesh A. Bogale, Gender and Migration Expert at the Organization for Social Science Research in Eastern and Southern Africa and a member of the Protracted Displacement Economies (PDE) team.

The number of Somali refugees in Ethiopia is 250,719, which represents 28.6% of all registered refugees in the country. There are relatively very few Somali refugees in the capital, Addis Ababa, with the vast majority in Dolo Ado (82%) and Jijiga (17%). Although the Government of Ethiopia has passed a law providing refugees with the right to engage in certain economic activities, and has made additional effort to support refugees in Addis Ababa, refugees in the capital are struggling to subsist. This blog post draws on interviews with a broad range of Somali women refugees in the Bole Michael area of Addis Ababa.

The particular challenges faced by women refugees

The experiences of Somali women refugees, both in their home country and enroute to Ethiopia, were nightmarish. None of them imagined they would ever have to flee their homes. They were exposed to dangers including gender-based violence on top of the daily struggles they faced to care for their family. A number of them had husbands and/or children who were dead or missing as a result of the conflict in Somalia, leaving them as traumatised heads of their households in a new country. Their displacement has left them vulnerable to loneliness, distress, anxiety and desperation. Hanan (all names in this article have been changed) lost her husband and two sons in Somalia, and then lost two daughters in the process of fleeing to Ethiopia. She said: “… I am only left with one sick son, whom I brought here with me, from a family of seven… I don’t see any hope.”

A combination of financial challenges and cultural norms means that women and girl refugees are barely able to manage. While they are grateful for peace and appreciate protection from forced return, the absence of an enabling environment for women refugees to create or get jobs is holding them back from flourishing. Moreover, as women and girls are burdened with the responsibility of caring for sick people in the household, they are unable to go out and look for jobs. Girls drop out of school to help their mothers in the house and to care for sick members as boys continue their studies. Sarah, whose father is sick, explained that this is what happened to her: “I had to take that decision for my two brothers to continue their education.”

No pathways out of poverty

While refugees certainly need a more comprehensive right to work, of equal importance is supporting them to access the labour market in practice. In particular, the lack of language skills on the part of Somali refugees is a real barrier to their prospects of obtaining employment. Policymakers pay little attention to creating an enabling environment for refugees’ self-reliance. Such limitations hinder refugees’ prospects of obtaining decent work and improving their income. This is particularly true for women, who face discrimination in both formal and informal sectors. As a result, unemployment remains a major challenge, causing significant psychological, social, and economic crises, which are disproportionately borne by women.

Samia is a woman refugee in Bole Michael who gets minimal support through humanitarian aid agencies and government assistance. She said: “I only receive so little from UNHCR [the United Nations Refugee Agency], which is not by any means enough to survive. My family and I barely make it each month. On top of this, I have a sick child whom I have to care for… it is a miracle if we eat twice a day.” There are many refugee women like Samia. All of them deserve pathways out of poverty.

The need for respect and tailored interventions

While humanitarian and government interventions are viewed favourably by refugees, our engagement with Somali women refugees has demonstrated that such interventions could be tailored to address the specific needs of women refugees. The Somali women refugees also talked about the negative mindset of others toward refugees. As Saida summed up: “…the labelling and disrespect is taking us down. …we too are humans, aren’t we?”

Women refugees are the most vulnerable; at the same time they are the most resilient – against all odds. Our discussions with these women refugees showed that they need to be listened to in order to understand their concerns, unique challenges, aspirations and strengths.

It also appears that neither third country resettlement, a process which is characterised by enormous delays leaving refugees in limbo for many years, nor return to Somalia are options for the refugees trying to build their lives in Ethiopia. We have to address women refugee issues in a way that engages with complexity and nuance. This is not a task that any one actor can achieve; rather it requires collaboration between various stakeholders, with women refugees always in the lead. As we bring stakeholders together, we will seek to engender collaboration, with women refugees’ voices at the centre of any initiatives.

This blog was originally posted in Protracted Displacement Economies (PDE) website. PDE is a project funded by UK Research and Innovation through the Global Challenges Research Fund (grant reference number ES/T004509/1).

Leave a Reply