This blog has been provided by Anna Ford, Media Relations Manager

It’s not often, as a media relations manager, that you have to have a retinal eye scan as part of your job. But when I went to CERN to see what Sussex physicists do there, it was an essential pre-condition of being able to go underground to see the experiments.

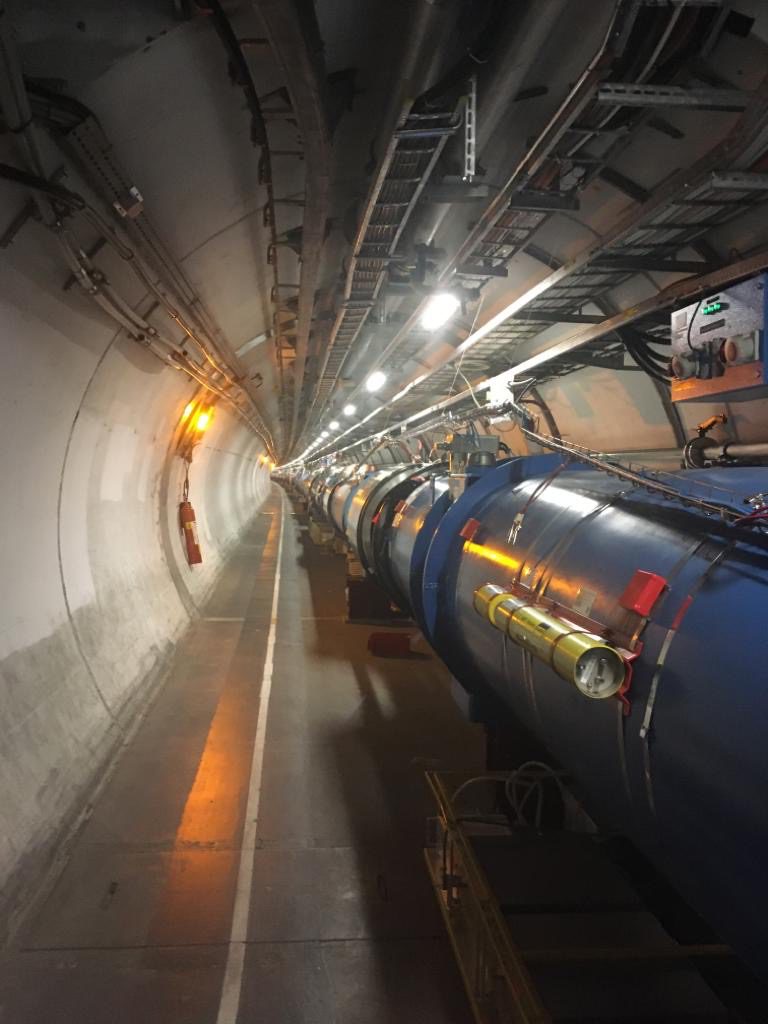

My press office and PR work has taken me to some pretty interesting places in the past: No. 10 Downing Street, Wormwood Scrubs (as a visitor, honest!), the press gallery at the Old Bailey… but nothing has ever been as downright cool as going 100m underground, hard hat at-the-ready, to see the Large Hadron Collider.

When a collision occurs it creates temperatures hotter than the sun.

It’s a 27km ring running underground beneath Geneva through which beams of protons are sped and deliberately collided. The beams move at almost the speed of light. It is simultaneously the coldest and hottest place in the universe: a bath of helium gas keeps the innermost tube at -273 Celsius which ensures the proton beams stay in line. And then when a collision occurs it creates temperatures hotter than the sun.

Our physicists – along with those from 37 other countries and 173 other institutions – analyse the data resulting from these collisions in the ATLAS experiment. They’re looking for ‘new science’ which might include a brand new particle or even proof that Dark Matter exists. It’s thanks to this data analysis that the Higgs Boson particle was detected in 2012 by a collaboration of physicists from Sussex and elsewhere.

Opportunity of a lifetime

I was invited to CERN as the media relations manager for the School of Mathematical and Physical Sciences, along with 15 press officers from the other UK universities working with CERN. Among our group were press officers from Oxford, University College London, Imperial College, Swansea, Glasgow and others. Frankly, we all agreed we had pretty much the best media relations jobs going.

We were incredibly lucky to not only be allowed into the tunnel containing the Large Hadron Collider itself, but also to visit experiments including ATLAS and ProtoDUNE (both Sussex collaborations). Accessing the experiments was an experience in itself, however. At various points we entered through cage-like security pods; had more retina scans; and were instructed to discard all food and drink because of a radiation risk. Only then could we descend 100m down a lift shaft to the experiments. It’s understandable that security is so high, of course. The experiments use chemicals and many also emit radiation. Every member of staff carries a dosimeter which records the level of radiation to which they’re exposed.

Representing Sussex

Aside from the incredibly cool science, one of the real joys of the visit for me was to meet with Sussex experts Professor Iacopo Vivarelli and Dr Nicola Abraham.

Iacopo has been working on the ATLAS experiment since 2005. He told me how exciting it was when the Higgs Boson was discovered. Two rival experiments (ATLAS and CMS) had simultaneously made the same discovery but hadn’t been allowed to tell each other. Both teams had discreetly tipped off the bosses at CERN. They were all invited to a meeting and when each team saw the other arriving, they understood immediately that they must both have discovered the Higgs Boson. Having two separate experiments – using different methods – making the same discovery provided CERN with the certainty it needed to formally announce the news.

The cool street art on the side of the ATLAS experiment building (which is Sussex’s main collaboration at CERN and is one of the experiments which found the Higgs Boson).

Iacopo told me that the CERN campus was abuzz with excitement during that period. But the work on Higgs is not over: these days the physicists are still combing data to learn more about its properties, such as its charge, mass and rate of decay.

Nicola completed her PhD with Sussex at CERN and has stayed on after as a post doctorate student. She told me how amazing it has been to work within a team trying to solve some of the greatest problems of the universe. Her next move is to take the data analysis skills she’s learned at CERN and apply them to the problem of climate change. She will shortly be joining an oceanography project in Germany where she will analyse and predict the impact of rising temperatures on sea levels.

I’m not sure there can be a greater testament to the value of Sussex’s work at CERN than this: the skills Nicola has acquired will now go towards tackling the grandest challenge of our time – our looming climate crisis.

Leave a Reply