by Katharina Rietzler.

Is pedagogical thought a form of international thought? If the study of international relations emerged from the study of race relations, as Robert Vitalis has suggested, education is central to international thought, even in the absence of educational mobility. In the United States, questions around education went to the heart of the American racial order in the era of Jim Crow segregation. Black women educators were the first to critically analyse the formation of attitudes in childhood as a problem in international-relations-as-race-relations. In this blog post, I will focus on two African American women and their international educational thought, Anna Julia Cooper (1858-1964) and Nannie Helen Burroughs (1879-1961).[1]

In their thought, they recognised education as intrinsically connected to challenging American racism in a world of empires, and before W.E.B. Du Bois popularized the idea of the ‘talented tenth’, a small group of educated leaders who would uplift the race. Amidst the resulting fierce debates that pitted proponents of industrial education against those who criticized the latter as entrenching African Americans’ socio-economic subordination, Cooper and Burroughs occupied a middle ground, with both insisting on the importance of classical education and economic self-sufficiency.

The history of African American club women forms another important context for Cooper’s and Burroughs’ international thinking, as does the structural discrimination that left teaching as one of the few viable professional avenues for African American women intellectuals. Black women’s clubs grew in prominence in the Progressive Era, forming the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACW) in 1896. Education became a fundamental concern of the movement – the NACW’s motto was ‘Lifting as We Climb’ – and many of its leaders were educators themselves. Mary Church Terrell, the first NACW president, studied at Oberlin College as a contemporary of Anna Julia Cooper. Terrell was also the first African American woman to be appointed to a school board in the District of Columbia. Cooper and Terrell both taught at the prestigious M Street High School in Washington D.C., the first African American public school – and the alma mater of Nannie Burroughs.

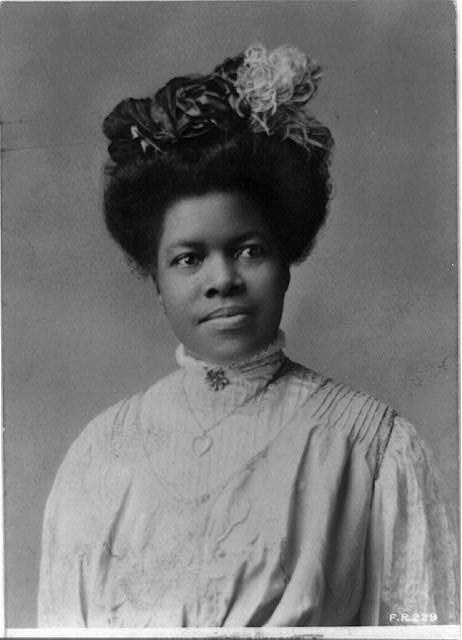

As a wide-ranging international thinker, Anna Julia Cooper analyzed ‘the international politics of racialisation, and its significance within international political economy, empire and state-making long before today’s scholars returned to this theme’, as discussed in a previous post by Kim Hutchings. Born into slavery in North Carolina, Cooper became the fourth African American woman to gain a doctoral degree, at the Sorbonne in Paris. In her thesis, Cooper developed a methodology for recovering the voices of marginalised people of colour in the French Empire.[2] For most of her life, though, she was a teacher, first in the segregated school system of North Carolina and then Washington DC. Her best-known book, published to wide acclaim in 1892, became A Voice from the South.

In a chapter on ‘The Higher Education of Women’, she speaks to key themes in women’s history in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century: women’s greater public and political role, the supporters and detractors of women’s education, and the beneficial impact of women as educators. But Cooper connects these concerns to core themes in international thought: race and civilization, war, hierarchy.

Cooper embraces the idea that maternal influence might temper chauvinism and racism, and couches the history of war and empire in terms of pedagogical failure:

‘Since the idea of order and subordination succumbed to barbarian brawn and brutality in the fifth century, the civilized world has been like a child brought up by his father. (…) Whence came this apotheosis of greed and cruelty? Whence this sneaking admiration we all have for bullies and prize-fighters? Whence the self-congratulation of “dominant” races, as if “dominant” meant “righteous” and carried with it a title to inherit the earth? Whence the scorn of so-called weak or unwarlike races and individuals, and the very comfortable assurance that it is their manifest destiny to be wiped out as vermin before this advancing civilization?’

Such ideas, Cooper, argued, were those of men, and while woman sometimes ‘parroted’ them, ‘her heart is aglow with sympathy and loving kindness, and she cannot be true to her real self without giving out these elements into the forces of the world.’ The ‘thinking woman’ would reform the ‘civilized world’, emitting those feminine qualities, that, together with masculine influence, would ‘produce for the twentieth century a higher type of civilization than any attained in the nineteenth’.

Cooper’s ideas may seem essentialist today, but they are remarkable in the way in which they claimed an importance for women’s education in world order and civilizational terms.

Nannie Helen Burroughs’ educational thought did so, too, but with greater attention to economic globalization and missionary Christianity. Like Cooper, Burroughs ran a school, the Christian National Training School for Women and Girls in the District of Columbia. Burroughs also worked for the Foreign Mission Board of the National Baptist Convention and became active in civil rights and women’s organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the NACW. She left a substantial corpus of published writings which has recently been collected in an anthology.

As Angela Hornsby-Gutting has shown, Burroughs’ educational work was not focused on racial uplift in the United States alone. From the early 1900s, Burroughs became concerned with the uplift of people of color throughout the world. She thought that African American women occupied a special role as missionaries spreading the gospel in foreign lands, exemplifying women’s leadership and self-sacrifice in the spirit of Christ. Burroughs regarded colonial oppression in Africa and racial oppression in the United States as intrinsically linked, referring to Africans as ‘our kinsmen.’ Her National Training School trained both African American and African women students. However, Burroughs’ efforts to professionalize domestic service also furthered women’s economic independence as wage earners in a time of economic boom and bust, and combated racist stereotypes.

In a 1902 speech entitled ‘The Colored Woman and her Relation to the Domestic Problem’ given at the Negro Young People’s Christian and Educational Congress in Atlanta, Burroughs, like Cooper, reflects on the ‘thinking woman’. She admits that domestic service may not conform to the aspirations of educated African American women ‘but educated women without work and the wherewith to support themselves … are not worth an ounce more to the race than ignorant women.’

Burroughs regarded the race problem as an international one, in which the forces of capitalism and the legacies of slavery pitted ‘white imported help’ against African American women seeking economic independence. The ‘demands of the hour’ were those brought about by the radical transformations of the Progressive period, marked by urbanization, industrialization and mass immigration. Burroughs’ case for professionalizing domestic science is also a plea for racial solidarity in the face of global white supremacy which put white workers at an advantage in the marketplace. In Burroughs’ speech, global labor movements and the global color line internationalize the question of industrial education.

More

practically-orientated than Cooper, and in a less lyrical voice than her,

Burroughs nonetheless also understood her work as a teacher to be of core

relevance to an international order in rapid flux.

[1] For a closer analysis of the category of ‘education’ in the context of women’s international thought see Katharina Rietzler, ‘Public Opinion and Education’, in Patricia Owens, Katharina Rietzler, Kimberly Hutchings, Sarah C. Dunstan (eds.), Women’s International Thought: Towards a New Canon (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, under contract).

[2] For a longer discussion see Vivian M. May’s essay on Cooper in Patricia Owens and Katharina Rietzler (eds.), Women’s International Thought: A New History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming January 2021).

Leave a Reply