Mark Knights, Professor of History at the University of Warwick, uses pre-twentieth century historical data to examine Britain’s long struggle with corruption and what can be learned from it today. Knights writes that anti-corruption is not always a linear journey and that good governance rests on the difficult task of finding the right balance between the necessary trust given to officials and the distrust required to scrutinise and constrain any abuse of that trust

In my recently published book Trust and Distrust: Corruption in Office in Britain and its Empire 1600-1850 I examine Britain’s long struggle with corruption during a key stage in the formation of the state and empire. Social scientists don’t often use historical data – and even more rarely anything before the twentieth century – but they should, since there are lessons to be gleaned from it. This blog tries to lay some of those out (and further analysis can be found here).

History suggests that anti-corruption is a long-term process, consisting of multiple moments of reform rather than a single ‘big bang’. Britain took about 250 years to move towards a recognisably ‘modern’ framework. The pace of reform accelerated after 1780 but the advances then rested on much earlier changes, innovations and debates. So it’s worth thinking hard about the factors that prevent change.

Britain’s example (replicated elsewhere) suggests that socio-cultural factors such as friendship, gift-giving, kinship and patronage are deeply embedded, lead to cronyism and capture of institutions, are hard to shift and mean that the boundary between licit and illicit behaviour is often shifting and difficult to define. Clarifying such boundaries, and societal norms more generally, is more than a top-down process of regulation – it also requires extensive public debate and even contest. That debate took place in Britain in a relatively free press from the seventeenth century onwards, something that was vital for a national conversation about ethics (even if this frequently centred on corruption as ‘scandal’). Without ethical conviction, rules were disregarded or evaded (as was repeatedly shown in domestic and imperial contexts).

Public pressure was also important in prompting top-down action – in the 1640s, 1690s, 1780s, 1830s the state responded to popular pressure. Much of that agitation resulted from macro factors such as war, which forced governments to raise taxation and increased a public desire to scrutinise how the money was spent, and periods of ‘moral renewal’, when religious sensibilities accelerated secular action.

State-formation is also a slow process. Indeed, for much of the pre-modern period the state was not a purely public entity but was reliant on private agents to deliver its objectives, such as justice and war. Hybrid public-private entities abounded: the East India Company, which created an eastern empire, was a private company given a state monopoly, and at home even jails were semi-private institutions, run by governors who were allowed to profit from their prisoners. Spelling out the dividing line between public and private was a process that took time – and was often calibrated through gross violations of what the public or government or a corporation saw as acceptable levels of profit for the semi-private agents, even if what was ‘acceptable’ was a key point of debate.

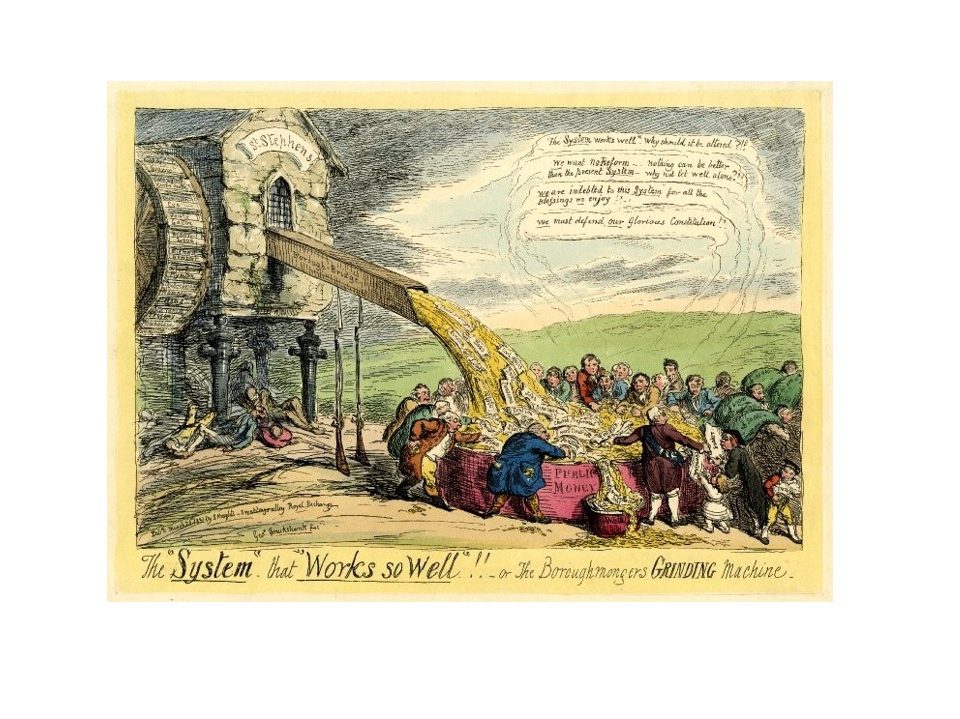

History also suggests that we might want to think about systems of corruption as well as individual or institutional failings. The concept of ‘systems’ first arose in the seventeenth century when it was applied to astronomy, music, the body, religion and eventually to politics too. In the eighteenth century commentators started talking about a ‘system of corruption’ and ‘corrupt systems’. A systems approach saw different fields as interacting: the corrupt parliamentary system rested on a corrupt financial system which funded corrupt wars which a corrupt elite used to feather their own nest. Many critics became convinced that corruption needed to be seen in the round rather than piecemeal, an idea that seems worth more attention. If today you leave the financial system out of reform, for example, you’ll neglect an important part of the interlocking pieces.

Other important terms, such as ‘interest’ and ‘trust’ similarly took off in the seventeenth century, enabling the development of ideas such as ‘conflict of interest’ and ‘breach of trust’. Trust is a particularly important notion in Britain’s corruption history, since it was a legal concept that moved from private estate law to public law, as a way of describing the obligations of office-holding. Trust required duties of selflessness, accountability, integrity and care that we now see as central to the standards required in public life. The wider point is that legal cultures really matter and shape how anti-corruption both evolves and is conceived (and hence also that different cultures will mean that anti-corruption has to be fitted to local contexts). Trust has also to be balanced by a measure of distrust, effected through formal means (national accounting bodies, for example) and informal means (through whistleblowers and the press). The art of good government rests on finding the right balance between the necessary trust given to officials and the distrust required to scrutinise and constrain any abuse of that trust. That’s a challenging task that needs constant reflection. It was certainly something the eluded politicians in Britain for several centuries.

Anti-corruption is often highly political, in many senses of the word. It was often used in British history to pursue personal, group and partisan interests. So we should ask what political (and indeed social, economic and cultural) work the allegation of corruption is doing at any one time and who or what benefits from it. Partisanship, in the British case, was a mixed blessing – on the one hand, it helped expose and pursue corruption, but on the other it often narrowed the debate away from systemic issues, polarised resistance to change and was dismissed as motivated by self-interest. Yet political support for non-partisan solutions was essential. The 1780s commission for public accounts, which formulated many principles that are recognisably the maxims of modern anti-corruption (officials should put aside their self-interest and have their public duty uppermost; they should separate private and public interests; they should not charge arbitrary fees for their services; they should properly account for public money) was not composed of politicians but had the support of the governments of the day, which needed to satisfy the public clamour for reform. Non-partisan commissions with political backing can be effective.

Finally, history suggests that anti-corruption is not always linear, with a threshold which, once passed, will always be maintained. For example, the parliamentary accounts committee, set up to make public expenditure more accountable, was abandoned after 1714 and not restored until 1780; and even now we seem to be retreating back into eighteenth century cronyism, patronage, conflicts of interest and the erosion of hard-fought principles and values. If that is right, we would do well to reflect on Britain’s long and painful struggle with corruption and learn its lessons.

Leave a Reply