Frank Vogl, Adjunct Professor at Georgetown University, co-founder of Transparency International, Chairman of the Partnership for Transparency Fund and author of “The Enablers – How The West Supports Kleptocrats and Corruption – Endangering our Democracy,” reviews a recent article by CSC Director Professor Liz David-Barrett.

Sussex University’s Professor Elizabeth Dávid‐Barrett’s new article – State capture and development: a conceptual framework– is published at a time when the leaders of democratic governments are grappling with the mounting challenges of autocracy and nationalist populism. Too often, these topics yield overly broad and general discussions without adequately delving into critical aspects of the core natures of the non-democratic regimes that abound today. This new article takes us towards a better understanding of the behaviors of governments that abuse their public offices as they serve themselves at the expense of their citizens.

To start with, the Professor’s definition is one that should become widely accepted and used. She writes:

“State capture is similar to regulatory capture but broader in scope. What is captured is not just regulation but core state functions, including the ability to shape the rules of the game through constitutional and legislative reform, but also the power of patronage which facilitates appointments to key power-holding or scrutiny bodies, and the power to distribute state assets and public money, and powers to regulate the space in which other oversight bodies such as the media and civil society act. State capture occurs when those who are entrusted with these powers abuse them consistently to shape the rules, appointments, allocation of state funds and rights in ways that make them less public-interest serving and more tailored to benefit narrow interest groups.”

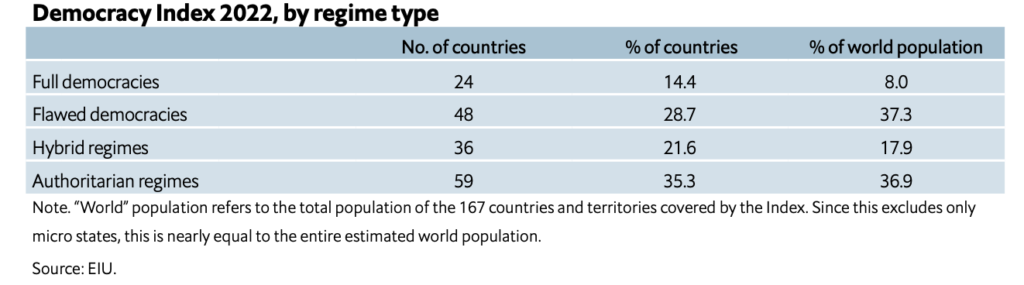

The importance of the article is underscored when it is recognized that approximately one-half of the world’s population live under regimes that pursue state capture. These are what the Economist Intelligence Unit describes as “hybrid regimes” and “authoritarian regimes” (see table below).

Looking at the operations of governments through the lens of state capture, as Professor Dávid‐Barrett encourages us to do, quite directly highlights who the victims of corruption are and how governments use diverse means to impoverish so many citizens as they seek both to increase their own wealth and secure their power. Too little research has focused explicitly on the impact of state capture on development and the section in this new article should serve to stimulate further substantive work with benefits for all development practitioners.

Such an exploration might take into consideration a wide range of issues not detailed in the new article, but that no doubt are prominent on the Professor’s agenda for further research and more publications. For example, I have long been fascinated by the question of why some regimes have managed to secure themselves in power and promoted state capture over decades, while others have only managed relatively short periods of successful state capture. Consider, for example, that Teodoro Obiang has been President of Equatorial Guinea in West Africa since 1982, or that Yoweri Museveni has been President of Uganda in East Africa since 1986, while Alexander Lukashenko has served as Belarus’s President since 1994. These long-term captors of their states contrast, for example, with others who for only a handful of years used their powers to plunder their nations such as the now jailed former Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak and South Africa’s former President Jacob Zuma who faces criminal charges today.

The degree of state capture and its duration under a single group of leaders depends in part on the extent to which those in power have captured all of the state’s institutions of justice and manipulated the judiciary to, in effect, permit the national political leadership to enjoy full impunity. I suspect this is not the whole answer. In many countries, from Tunisia in 2012, to anti-Zuma protests from 2017 in South Africa, public protests have at times been so overwhelming that they have been the prime engine for ousting oppressive national leaders. With the rise of social media as a tool for organizing protests and the increased skills of civil society activists, the number of powerful protests by citizens has been formidable, as evident from the findings of the Global Protest Tracker developed by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. This is an increasingly important aspect of state capture and Professor Dávid‐Barrett, who discusses civil society in her article, may wish to expand on this in the future.

Another feature of state capture worthy of deeper research and debate concerns the roles that the military plays in some countries. The military has been the power behind the governments of Pakistan for many years, stepping in to take control at times when it has considered appropriate to secure stability and its own real power. Egypt has long been under the iron fist of military rule, as have numerous other countries – and in every case the military has acquired businesses, developed its own enterprises to secure public procurement contracts, and taken control of state-owned enterprises.

Professor Dávid‐Barrett draws attention to the close ties between business and political elites in conspiring to secure state capture. In many countries, it is useful to consider how the business elites attained their powerful positions in the first place. Professor Louise Shelley in her books, “Dirty Entanglements: Crime, Corruption, and Terrorism” (2014) and “Dark Commerce: How a New Illicit Economy Is Threatening Our Future”(2018), provides evidence of the close ties in many countries between business elites and organized crime. The late Professor Karen Dawisha in her book “Putin’s Kleptocracy – Who Owns Russia?” (2014) and journalist Catherine Belton in her book “Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took On the West People” (2020), both detail the formidable roles that organized crime played in Russia in the 1990s in aiding and abetting businessmen and politicians to attain state capture.

Indeed, this new article by Professor Dávid‐Barrett is likely to trigger much further research on state capture and prove to be a scholarly landmark that provides inroads to understanding not only the nature of hybrid regimes and authoritarian regimes, but the challenges that the victims of corruption confront in so many countries today.

[…] by the Wagner Group in state capture. You can read his further reflections on state capture in this review of the seminal article on the subject by Prof Liz […]