By Sara Vestergren and John Drury.

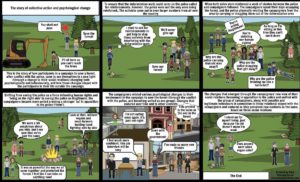

Most of us have some experience of collective action, even if it is only walking past a rally on our way to work, or signing a petition. However, our involvement might extend the casual everyday experience of collective action and we could find ourselves deeply involved in a campaign that subsequently changes us. For example, people learn new skills and obtain new knowledge, gain in self-confidence, change in consumer behaviour and radicalattitudes to name a few. One might think that these changes are only apparent within the immediate context of the campaign. However, for some participants these changes can endure and extend to other areas of life. This happened to some of the campaigners in Sweden who were fighting to save a piece of forest from becoming a limestone quarry in the summer of 2012. Locals had been fighting for the forest for about ten years before that. During that summer, activists travelled to the island and set camp in the forest to hinder deforestation. Together with some of the locals, they spent their days being in the way of the deforestation machines and sitting in trees.

Our study of the campaign suggested that the psychological changes the participants experienced can be explained in two parts. First, there was a conflictual relationship with another group (in this case the police) that contained a contradiction between expected outgroup behaviour and experienced outgroup behaviour. Second, through sharing an oppositional relationship to the outgroup, the participants came to feel closer and more alike within their own group – they became united.

In the campaign to save the forest, the local island police were too few in numbers, so they called for reinforcements from the mainland. When the police reinforcements (73 officers, horses, etc.) arrived, the campaigners got some reinforcements themselves and went from being about 20 people in the forest to 300. This was followed by a week of clashes between the police and the campaigners. Most of the campaigners expected the police to be on ‘the right side’, but experienced the police behaviour to be the opposite: supressing their right to protest (experienced as illegitimate) and treating all the campaigners the same by forcefully carrying or dragging them out of the area (experienced as indiscriminate). This made the campaigners become both oppositional and united, consequently shifting in the way they viewed themselves and the rest of the world. The campaigners talked about their changes and choices, such as becoming vegan, more confident, or more radical, as part of a larger framework based on justice and ethical fairness. The changes were related to their new way of seeing themselves as activists, adopting an ‘activist worldview’ based on the justice framework.

To keep these changes stable over time the campaigners needed to keep their ‘activist’ view of themselves and the world – their social identity – alive, including the justice content of that identity, the larger cause of fighting injustice in all areas of life. One key feature in the identity salience was the perceived enduring relationships with other activists. Through staying in touch with other campaigners (in real life or online), they kept the activist identity, and changes such as empowerment, alive over time.

The full text version of “How collective action produces psychological change and how that change endures over time: a case study of an environmental campaign” is published in British Journal of Social Psychology and can be found here.

Leave a Reply