By Sara Vestergren.

We often hear about the difficulties and negative consequences of protesting and activism, and these negative consequences might be the reason why you are on this page in the first place. Some protest related experiences can leave the protester/s with long-term physical and mental scars. There are reports of activists losing their jobs, getting burned out, being ridiculed and criminalised, getting arrested and/or treated violently by the police. For example, at the Barton Moss Community Protection Camp, Greater Manchester Police made 231 arrests which resulted in 77 complaints to the Greater Manchester Police. Of these 77 complaints, 40% were related to police misuse of force. However, these negative consequences of participation in protest only tells half the story. What about the positive benefits of protesting – are there any (apart from making the world a better place of course)?

No matter where in the world we protest or what we protest for/against – our participation will have consequences. In a recent summary of personal and psychological consequences of protest and activism, 19 different types of consequences were identified, most of them of positive nature. For example, through participating in protests we can learn new skills such as organisingworkshopsand managing the legal and societal system, we can change our consumer behaviour, we can become empowered, and we can gain new friendships and relationships.

Furthermore, participation in protests can improve your general health and well-being, self-esteem, confidence, and health. Protest participants have reported both increased general well-beingand more specific consequences such as decreased migraines and easing of arthritis symptomssuch as more movable joints and less joint pains, and increased long-term happiness. There is also research in support for increased self-esteemthrough participating in protests. For example, through the experience of standing up for what we believe in, together with others that share our views, during a protest we can become empowered and increase our confidence in ourselves, which may then stay with us and be applied to other areas of our lives.

So how do these changes come about?

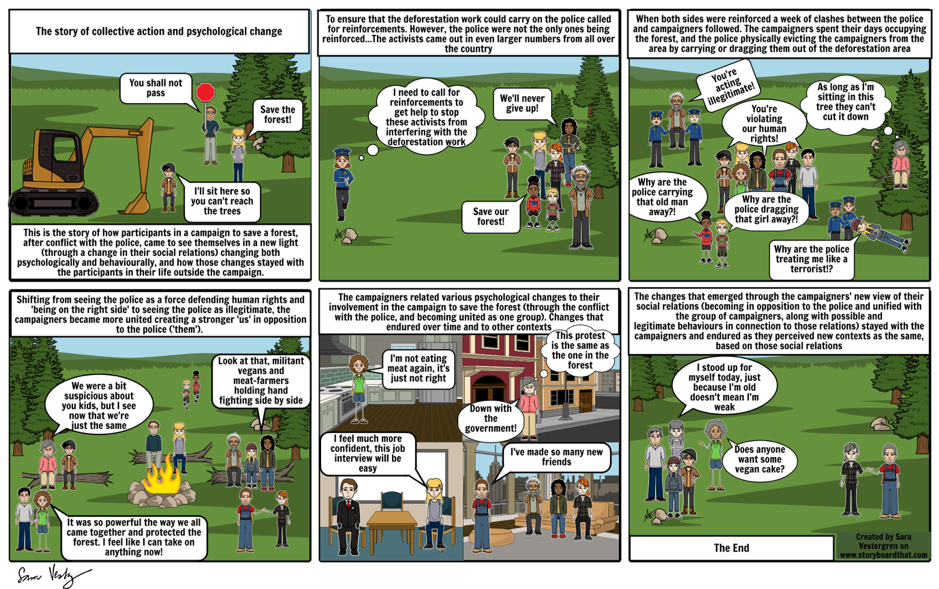

Is it enough to just go and stand in the middle of a protest, breath in the air and suddenly you’ve benefitted from it? Of course not, if life was only that simple. However, there seems to be two crucial processesthat leads to these various consequences; conflictual interaction with an outgroup(often the police) and supportive interaction within the ingroup(other campaigners). Firstly, when we perceive the police to act illegitimate and indiscriminate, we increase our opposition or become oppositional towards that outgroup (the police). The police here supress the right to protest (experienced as illegitimate) and treats all campaign members alike (experienced as indiscriminate) by for example forcefully dragging fellow campaigners away or dispersing the whole group of campaigners from an occupied area. There may initially be a perception of the police to be a force on ‘the right side’, a force that will do the right thing. However, when the police then act in opposition to our perception of how they should act a contradiction between our expected and experienced view of them emerges creating a shared oppositional identity amongst the protesters. Secondly, through our new opposition towards the outgroup our ingroup becomes more united, we feel closer to each other and feel as others will support us in our views and actions. This ingroup unity makes us more alike. These two processescan make us shift in the way we see ourselves and the world, and consequently, how we act in the world.

What happens when the protest is over?

Do we change back to our pre-protest selves when the protest is over? The enduranceand strength of the changes seems to be linked to our relationships with other activists/campaigners. To sustain the changes over time we need to keep our ‘activist’ view of the world and ourselves alive. This also means keeping the content of that identity (such as fighting injustices) alive and adapted to all areas of life. For example, in studies of a group of Swedish environmentalistsit was found that the activists who stayed in touch with other activists also stayed changed. This was explained through the activists being able to feel connected to the campaign issues and causes and thereby keep their environmentalist identity alive – with everything that means – for example, recycling, reducing meat consumption, reducing consumption in general, and staying active in other campaigns relating to environment or human rights issues. So, by staying in touch with other campaigners/activists, online or physically, we can keep our view of ourselves and the world alive and thereby sustain the changes such as empowerment, health benefits, oppositional view and diet.

To sum up, protesting may have its downsides, however, it would be very naive to claim that protesting isn’t good for you (and the world). This is not to say that we all change in the same ways, or that everyone changes – some may just become more convinced and enhance their opinions and behaviours. Additionally, the police response to protests may in itself be counterproductive (for the police) as it creates a stronger and more united opposition that fights more and harder to achieve change.

If you have any queries or want more information about the studies, contact sara.vestergren@icloud.com

This article was originally published in Protest Justice.

References

Boehnke, K., & Wong, B. (2011). Adolecent political activism and long-term happiness: a 21-year longitudinal study on the development of micro- and macrosocial worries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37 (3), 435-447.

Cherniss, C. (1972). Personality and ideology: A personological study of women’s liberation. Psychiatry, 35 (2), 109-125.

Cox, L. (2011). How do we keep going? Activist burnout and sustainability in social movements. Helsinki: Into-ebooks.

Drury, J., & Reicher, S. (2005). Explaining enduring empowerment: a comparative study of collective action and psychological outcomes. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 35-58.

Drury, J., Reicher, S., & Stott, C. (2003). Transforming the boundaries of collective identity: From the ‘local’ anti-road campaign to ‘global’ resistance?Social Movement Studies, 2, 191-212.

Gilster, E. (2012). Comparing neighbourhood-focused activism and volunteerism: psychological well-being and social connectedness. Journal of Community Psychology, 40(7), 769-784.

Gilmore, J., Jackson, W., & Monk, H. (2016). Keep moving!: report on the policing of the Barton Moss Community Protextion Camp. Liverpool: CCSE and York: CURB. http://researchonline.ljmu.ac.uk/3140/1/BM%20Report%20Published%20Version.pdf

Gorski, P., Lopresti-Goodman, S., & Rising, D. (2018). “Nobody’s paying me to cry”: the causes of activist burnout in Unites States animal rights activists. Social Movement Studies, 18 (3), 364-380.

Hannsson, N., & Jacobsson, K. (2014). Learning to be affected: subjectivity, sense, and sensibility in animal rights activism. Society & Animals, 22(3), 262-288.

Kaplan, H., & Liu, X. (2000). Social protest and self-enhancement – a conditional relationship. Sociological Forum, 15 (4), 595-616.

Klar, M., & Kasser, T. (2009). Some benefits of being an activist: measuring activism and its role in psychological well-being.Political Psychology, 30(5), 755-777.

Reicher, S. (1996). ‘The Battle of Westminster’: developing the social identity model of crowd behaviour in order to explain the initiation and development of collective conflict. European Journal of Social Psychology, 26, 115-134.

Shriver, T., Miller, A., & Cable, S. (2003). Women’s work: women’s involvement in the Gulf War illness movement. The Sociological Quarterly, 44(4), 639-658.

Stuart, A., Thomas, E., Donaghue, N., & Russell, A. (2013). ‘We may be pirates, but we are not protesters’: identity in the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society. Political Psychology, 34 (5),753-777.

Van Dyke, N., & Dixon, M. (2013). Activist human capital: skills acquisition and the development of commitment to social movement activism. Mobilization: An International Journal, 18 (2), 197-212.

Vestergren, S., Drury, J., & Hammar Chiriac, E. (2017). The biographical consequences of protest and activism: a systematic review and a new typology. Social Movement Studies, 16 (2), 203-221.

Vestergren, S., Drury, J., & Hammar Chiriac, E. (2018). How collective action produces psychological change and how that change endures over time – a case study of an environmental campaign. British Journal of Social psychology, 57 (4), 855-877.

Vestergren, S., Drury, J., & Hammar Chiriac, E. (2019). How participation on collective action changes relationships, behaviours, and beliefs: an interview study of the role of inter- and intragroup processes. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 7 (1), 76-99.

Leave a Reply