By Carina Hoerst, Klara Jurstakova, Nuria Martinez, Sam Vo, & Sara Vestergren

On Thursday, 8 September, 2022, HM Queen Elizabeth II died at Balmoral Castle after a 70-year-long reign. A 10-day period of mourning was announced ending with the funeral on 19 September, 2022, in Westminster Abbey. The expected crowds to gather around places of significance in relation to the Queen’s passing created an ample opportunity to advance and test our understanding of crowd psychology. Planned and led by researchers from the University of Keele and University of St Andrew’s, a group of researchers from several UK universities mobilised within days. The aim was to collect ethnographic data (e.g., short interviews, field notes, etc.) in relation to crowd participants’ experiences and motivations in both Edinburgh and in London. The crowds would be an extraordinary opportunity to explore emotions, motivations, and transformations.

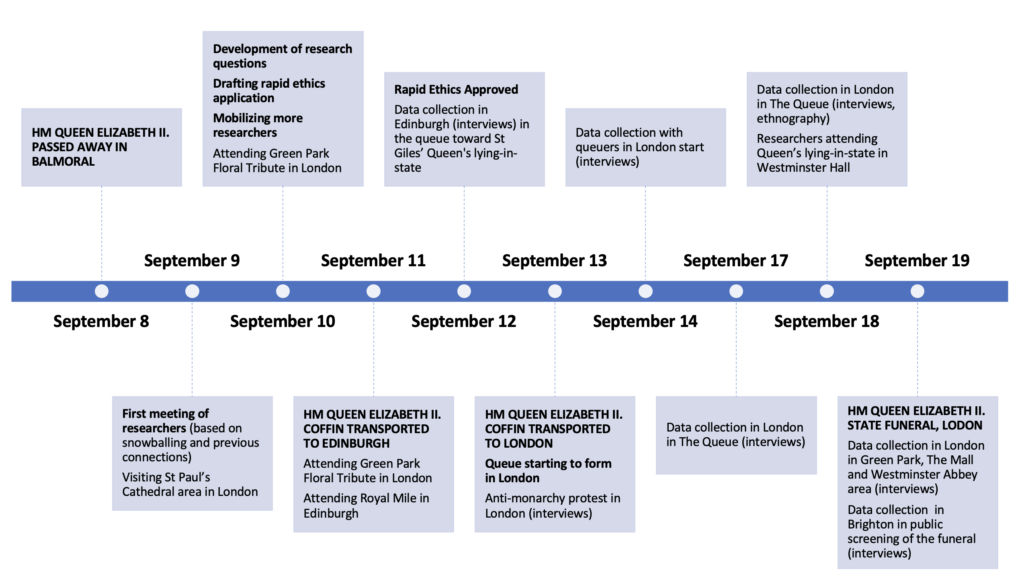

Conducting research when it happens (“rapid response research”) brings about unique challenges. However, the experience in the group facilitated pulling together a large team, as well as preparing and submitting the ethics documentation quickly. The ethics were submitted to the lead organisation through the rapid-ethics structure. The project received ethical approval for the study by noon on the Monday after the Queen’s passing. We expected large crowds in both Edinburgh and London, but no significant conflictual intergroup interaction. Hence, the outline and recommendations below are in relation to crowd events without conflictual intergroup relations.

Late afternoon on Friday 9th September we met online for the first time to discuss the project. At that time, it was still unclear whether ethics would be approved in time, so we needed to have various plans depending on when (and if) we could collect data. While the ethics application was being prepared and under review, some colleagues visited sites of potential significance to be in a better position to plan for our project. On Sunday 11th September we met to decide on the main aims and questions, as well as appointed a person of contact for Edinburgh and one for London. We also set up documents where we could add our availability for data collection during the week to come.

Once the ethics were approved our team in Edinburgh started conducting short “vox pop” interviews in the crowds, for example in the queue for lying-in-state at St Giles. Additionally, we took field notes, photos and videos of the crowds. As crowds started to gather in London on the 13th, we started collecting data there as well. On the 14th more people started to queue, and the queue to the Queen’s lying-in-state officially opened. We continued to collect data from people in the queue over the next few days and on Sunday 18th September we joined the queue as attendees to further our understanding of our participants’ experiences (and our own). Finally, on the 19th, the day of the funeral, we collected data from various crowds gathered in London. Additionally, we collected data from one of the funeral screenings (Palace Pier, Brighton) on the 19th of September. Through our Rapid Response project, three key areas of importance were acknowledged: communication, legitimacy, and flexibility.

Communication

Communication both within the research team, as well as with participants and other members of the research context are key to all projects. We met online daily to share experiences, practices, narratives, and areas to explore further. As we would be working in large crowds, we expected phone and internet outages. To ensure that no one would get lost in the large crowds we decided to work in pairs and have physical meeting points (dynamically decided over time) in case we got separated. To have quick access to each other within the research team we created WhatsApp groups which allowed for information to be quickly disseminated within the team (e.g., closed-off areas, or crowds of interest), as well as sharing live location and reporting safe return home as a safety measure. To facilitate both data collection and that communication was upheld throughout we brought extra power banks so we could charge phones and other devices while in the field.

Legitimacy

In addition to good communication within the team, collecting data also required good communication with participants and the public. For the legitimacy of the study and data collection, as well as our own safety, we introduced ourselves as researchers (aided by wearing our university IDs visibly). Also, working in pairs allowed us to introduce ourselves as part of a research team which seemed to evoke more trust and a relaxed atmosphere than approaching people alone. This provided us with some interviews that turned into informal focus groups and allowed more people to be part of the research project. Working in pairs also allowed for one researcher to lead the interview and the other to do the recording and focus on follow-up questions. We were aware that introducing ourselves as researchers, could invoke a perception of us being “experts”. Therefore, we emphasised that we were interested in the participants’ experiences. As with most qualitative research, it was important that our participants were subjects rather than objects.

Stepping out of our research identity and being a “naïve” researcher is difficult. In ethnographically designed studies, the binary researcher/participant divide becomes blurred as we become participants in our own study. The blurred lines became very obvious when a few of us were in “the Queue” together with a group of participants and became part of their group trying to find a balance between professional and personal. Becoming part of the phenomenon we sought to examine provided unique insights. However, there were instances where the personal and professional were clearly divided. For example, some discussions in the crowds would include content that we did not necessarily agree with. To avoid creating a distance between us and our participants we, therefore, engaged in selective silence (and listening) for the personal to keep the professional. The complex task of moving beyond the binary has previously received criticism for not being “objective science”. We argue that embedding yourself in the context can facilitate advances in our understanding of participants’ narratives, as well as it can aid us when conducting future interviews. However, it is also important that we take a reflexive approach and acknowledge ourselves and our influences in the research process.

Flexibility

The need to be able to adapt to the situation, without compromising the trust and legitimacy of the project, requires field researchers to be flexible and think on their toes. We also needed to be flexible in relation to the emotions in the crowd, for example, that people mourn in their own way. As a rule, we did not approach anyone who seemed to be grieving or upset. Even though some in our team were included in the “ingroup” of the crowd by participants there were instances where participants made a clear distinction, categorising members of the team as “outgroup”. For example, there were instances where team members who identify as persons of colour were asked about their “true” place of origin although they at length explained that they live and work in the area. Despite being in the same queue, the often-mentioned notion of “this is how we [the British people] mourn our Queen” never extended to the researchers who stood in the same queue with them the whole time. However, having some team members in the position of outsiders, enabled more varied accounts of the events. Hence, we could observe a difference in the way that the crowd engaged with a perceived insider (i.e., ingroup) versus how they explained their experiences to a perceived outsider.

The required flexibility also relates to practical and physical dimensions. During crowd events, there are often road closures and restricted areas. We used information from, for example, the government to understand where spaces for crowds were organised. For future crowd observations on a similar scale, we would recommend appointing a team member who could gather such information more systematically to avoid unplanned setbacks. For example, on Monday 19th, we were trying to get back to Westminster Hall from Trafalgar Square just after 6am. During the few hours, we had been away big walls had been erected on most streets leading to Westminster Hall hindering us from getting back to the area on foot. Instead, we followed the crowd, which had also tried to get to the Westminster Hall area, to Green Park, and later towards Hyde Park where the funeral was to be screened. This unplanned movement ended us up in a stationary crowd trying to get to Hyde Park. However, due to road closures what started as a march had become a stand-still crowd where we, as everyone else in the crowd, was stuck. It is likely that with better geographical planning we could have avoided getting (unintentionally) stuck and had a better understanding of where movement in the area was possible.

Even though conducting a rapid response ethnographic study of the crowds in relation to HM Elizabeth II’s passing demanded a lot of the team both physically and mentally, it was a once-in-a-lifetime experience. Being researchers does not exempt us from being humans. Some team members had similar experiences as our participants, for example, some were reminded of a passed loved one and others developed a fear of missing out and were frustrated that they had to leave the queue to get their last train home. Overall, it was an overwhelmingly positive experience that brought us closer as colleagues and friends. By studying the collective, we became the collective. Similar to when a really good series ends, we can’t wait for the next season (project) to begin.

Leave a Reply