This post is written by Dr. Paul Gilbert and was originally published on the Sussex Anthropology blog ‘Culture and Capitalism’.

There is little more grating, for those of us who work in Higher Education, than those portions of the British media who insist on propagating lazy stereotypes of ‘work-shy millennials’. Year on year, the hours our students spend in employment outside of the classroom only seem to increase. At the same time, efforts to ensure our courses are relevant and up-to-date only raise the number of publications and news wires we now expect our students to monitor. The demands placed on our students’ time by the need for paid employment alongside their studies is something of an open secret: most of us are well aware of it, but not quite sure what to do about it – especially when a 30-credit module is designed to require 300 hours of learning.

Earlier this year, Sussex’s School of Global Studies piloted a survey of student paid work commitments, in an effort to make visible what most of us already knew, to learn more precisely about how paid work was impacting on studies, and set in motion efforts to respond to the burdens our students are facing. We received 140 responses (a little over 10% of our student body), from members of our undergraduate, taught postgraduate and research postgraduate communities.

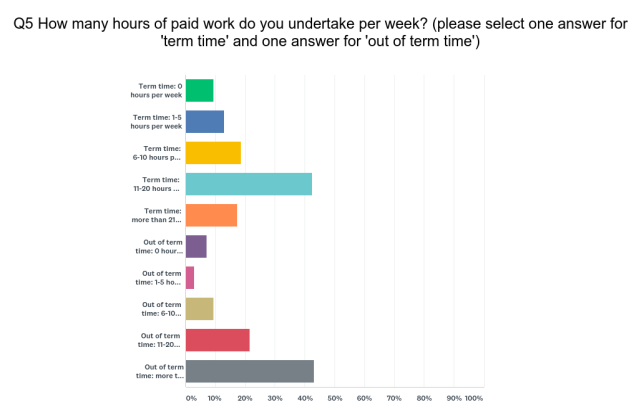

Our students work predominantly in hospitality and retail, with 44% working on zero hours contracts, and around 30% in open-ended or permanent roles. Perhaps the most significant finding of our survey is that during term-time more than 40% of students work 11-20 hours per week, and 18% work more than 21 hours per week. The figures are not dissimilar for out-of-term work commitments (see the chart below).

In effect, this means that more than 50% of our students are already studying ‘part-time’. The working time directive states that you cannot engage in paid work for more than 48 hours per week without opting out: working 11-20 hours per week during term-time is equivalent to working 12 to 42% of the maximum, before classes, assessments and private study are factored in. It is no wonder that many of the students surveyed described difficulties in keeping up with their readings, as well as mental health implications, when asked: “In what ways have your studies at university been affected by time spent on paid work?”

I work two full days a week, so for those two days I don’t have time to get any university work done. It is stressful with time management however I need the money and am managing as best I can.

I’ve not been able to put in sufficient time to my studies when having to work 25 hour weeks to pay for rent/bills/living whilst studying.

Exhaustion, unable to participate in class/do preparation for class due to exhaustion.

I feel that I do not have a weekend therefore never really have a break to get work done and refresh myself for the next week and prepare for lectures. Also added stress of paid work affects my university work as I am not relaxed.

Working in hospitality – one of the biggest employers for students in Brighton – creates its own particular stresses:

I feel they have been extremely affected. Especially in my job in a restaurant where i stayed until close and then cleaned up, meaning i was often staying up until 1am on Uni nights, then getting up at 7:30 for my 9am lecture commute from town. I was often too exhausted to concentrate properly and found I could not enjoy much of a social life as when I wasn’t working at my job I was catching up on lectures and readings.

Usually I have to go straight from work to uni or visa versa so sometimes I miss lectures. Also sometimes I don’t finish until 1am so often find no time to do wider reading.

I’ve felt a massive effect, not in the obvious “work hours impinging on study time” way, but in terms of sleeping pattern. I work in a student bar that opens into the early morning, so regardless of how many shifts I do (usually 3 during term time), it’ll obviously have a knock on effect on the following day, and in more general terms I really struggle to wake up early and make a full day as my body’s used to a 3am bedtime. It’s also not as easy as moving to a day job — with my financial situation being as tight as it is, I am able to work many more hours alongside uni in a bar job than in a cafe etc that would only allow shifts on my non-contact time days.

An inability to participate in the many extra-curricular activities, workshops and research seminars that Global Studies prides itself upon was also noted by several respondents.

The fact that student loans do not cover rent or living expenses – thus requiring more shifts be taken on, leading to more missed classes – was also highlighted by several students, who described themselves as caught in a ‘Catch-22’ situation. A number of respondents noted the particularly high cost of living in Brighton, which is no doubt a significant factor, but these issues are felt more widely across the UK. In Swansea, for instance, newly built student accommodation costs £5,520 for a 40-week tenancy, while the basic student loan is set at £3,821. Only those students whose household income is below £45,000 would be able to cover their term-time accommodation with their loan – but they would still be without additional funds for living expenses unless they took on paid work.

At Sussex, students whose household income is less than £42,875 are eligible for the First Generation Scholars financial support scheme – although only 35% of our respondents qualified as FGS, and around 20% were unclear. (Some students also noted that they were the ‘first’ of their family to attend university, but did not qualify under the scheme). Below the £42,875 household earning threshold, students are entitled to an increased loan (up to £6,095) up to a maximum of £8,200 for students whose families earn less than £25,000 per year. One key issue here is that these increased loans have replaced the grant scheme that was abolished in 2016/17.

This means that students from lower-income families are obliged to enter into more debt – which will take longer to repay – than students from higher-income backgrounds. Andrew McGettigan has described this as a ‘tax on social mobility’, since students receiving the maximum loan will now pay more back the greater their lifetime earnings turn out to be. In effect, the lower your family’s income, and the greater your post-university earnings turn out to be, the more you pay for your degree; someone from a higher-income background making the same earnings across their lifetime will end up paying less towards their tuition fees.

So why was the maintenance grant abolished? One clear reason seems to be that whereas grants would count as government expenditure and increase the national deficit, student loans do not show up as government spending until they are repaid or written off in 30 years’ time. Bizarrely, the income earned on outstanding loans is being treated as ‘income’, reducing the deficit figures. As McGettigan notes: “Were the government to introduce a year-long moratorium on all student loan repayments, the deficit would benefit in the short-run. Repayments go down and long-run costs go up but there would be more interest accruing against outstanding balances – hence more income today!”

The pressures students now face in terms of balancing paid employment and time spent on their studies are not easy to solve. Simply reducing the expectations placed on our students in terms of hours of study needed to complete the required number of credits is clearly not the right solution. Responding to an increase in financial pressure by reducing the quality of your education is in nobody’s interest. We do, however, need to see more calls for the restoration of the maintenance grant, the abolition of which seems to do little beyond massage the government’s deficit figures and work against any measure of social mobility or equity.

This is not enough, of course. Policymakers need to address the high cost of rent, driven by a well-documented broken housing and land market. The availability of work in industries where shifts are less disruptive for students is more of a challenge: Brighton’s economy runs on hospitality and retail, and at least some of our respondents were glad of the opportunities work in these sectors provided for them. But the creep into many workplaces – including into academia – of the expectation to do unpaid work certainly needs to be challenged, and might be an area where the School, University and Students’ Union could offer support. As one respondent noted:

Another issue that might be of interest to your study is the out-of-work commitments that even casual contract jobs are beginning to expect. For example I’m required in my job to maintain the social media presence of my bar on designated days, posting/answering messages etc (of course, doesn’t count as paid hours). This completely reframes the norm of a part-time job and means that work and uni can converge in the same setting in a rather stressful way, contrasting with the more traditional idea of leaving the doorstep of the workplace and switching into ‘uni mode’.

It is also vital that we are aware of the effects of the government’s ‘Hostile Environment’ policy, especially on Tier 4 PhD students. Several noted they were unable to support themselves within the 20 hour work limit, and were prohibited even from access to the ‘gig economy’, in part because of the definition of gig economy workers as ‘self-employed’ – something that has recently been contested in the British courts. For example:

The student visa curtails the amount of hours I’m allowed to work to 20, which hypothetically curtails the amount of money I could make, though I only work 12 hours a week and find that any more would probably be unmanageable. It also prevents me from doing any freelance or self-employed work (even Deliveroo falls in this category) so it limits what jobs I can take on.

With the fees our international PhD students are charged set at the astronomical £16,750 per year, it is no wonder that many – even those supported by a scholarship – need to enter into paid work.

The pressures our students face are shaped by the broader political economy of the UK as a whole – from migration policy to housing, employment law to the politics of deficit-reduction – and there are no easy solutions presenting themselves. But what we can do is to contribute to calls for the restoration of maintenance grants (and, ideally, the reduction or abolition of tuition fees), and make visible within the School the scale and nature of pressures that paid work commitments place on our students. We would also welcome any suggestions that you might have, for mitigating the pressures that paid work commitments place on your studies and mental health. Please contact S.Laastad-Dyvik@sussex.ac.uk and E.Roycroft@sussex.ac.uk with any feedback you may have.

Leave a Reply