Written by Finlay Etherington

kyun banaate ho mujhe mazhab ka nishaana

main ne to kabhi khud ko musalmaan nahi maanaa

apne hi watan mein hoon magar aaj akeli

urdu hai mera naam main hoon ‘khusrav’ ki paheli

Why do you make me a target of religion?

I have never considered myself solely a Muslim.

I am in my own homeland, yet today I stand alone.

My name is Urdu; I am the enigma of Khusro

2 years ago, sat in the foyer of a hotel in New Delhi during the peak of the monsoon season, I was chatting to the reception staff in Hindi over a glass of chai. Half-way through the conversation, the owner of the hotel remarked “You are sounding like a Muslim, and we don’t like Muslims”. I decided to refrain from using too many words which would, in their eyes, be considered alien to Hindi, but are nonetheless popular in Bollywood songs and daily-speech. This language to which they referred was Urdu, a language which is mutually intelligible with Hindi, born in the very area which the hotel was situated, the heart of Old Delhi. Shaped by the confluence of local Indian languages interacting with Persian, Arabic and Turkish, Urdu’s origins are undoubtedly Indian. This interaction has since sparked a desire to understand the Hindi-Urdu nexus, and what effect this kind of rhetoric is having on those who claim it as a native language (Ahl-e-zabaan).

Last spring I was fortunate enough to be awarded the Nicola Anderson Award, which funded the fieldwork, for my thesis I carried out across the Hindi-belt during the summer of ‘24. The purpose of my research was to explore the current and future status of Urdu in Northern India, which I will link to my wider thesis concerning changes to Muslim identity in Northern India. So began a 3 week period of fieldwork stretching from the capital Delhi, across the Punjab, and into Jammu and Kashmir.

Whilst I knew Northern India well and can speak Hindi / Urdu, this was my first time conducting research, and I felt slightly out of my depth to begin with, wondering how I was going to pull together all of the links. One of the major hurdles was trying to organise semi-structured interviews requiring formal, written consent – it turned out to be quite a nightmare. Through a contact at the University of Sussex, I had been kindly offered a chance to be hosted in Jammu, where I was assured I would have access to participants – however, I was really hoping for at least one interview before leaving the capital.

Whilst acclimatising to the weather in Delhi, I set aside a few days to organise the admin-side of the fieldwork and to get my bearings. To pay my respect, I visited the shrine of one of the greatest Urdu poets, Mirza Ghalib. In the vicinity of his tomb in the Nizamuddin area of Delhi can be found the Ghalib Academy, set up in honour of the 19th century poet and also the Sufi shrine of Nizamuddin Auliya and his spiritual disciple, Amir Khusrow. Amir Khusrow is known as the ‘father of Qawwali’, a Sufi devotional style of music found in the sub-continent. During this time I ended up meeting countless people with whom I discussed my project and I attempted to invite some of these people for an interview, however, the vast majority of the time people were far happier to simply say ‘yes that’s fine, go ahead’ but weren’t keen on signing formal documents. This would set the tone for much of the trip and I’d often lose the chance of an interesting interview.

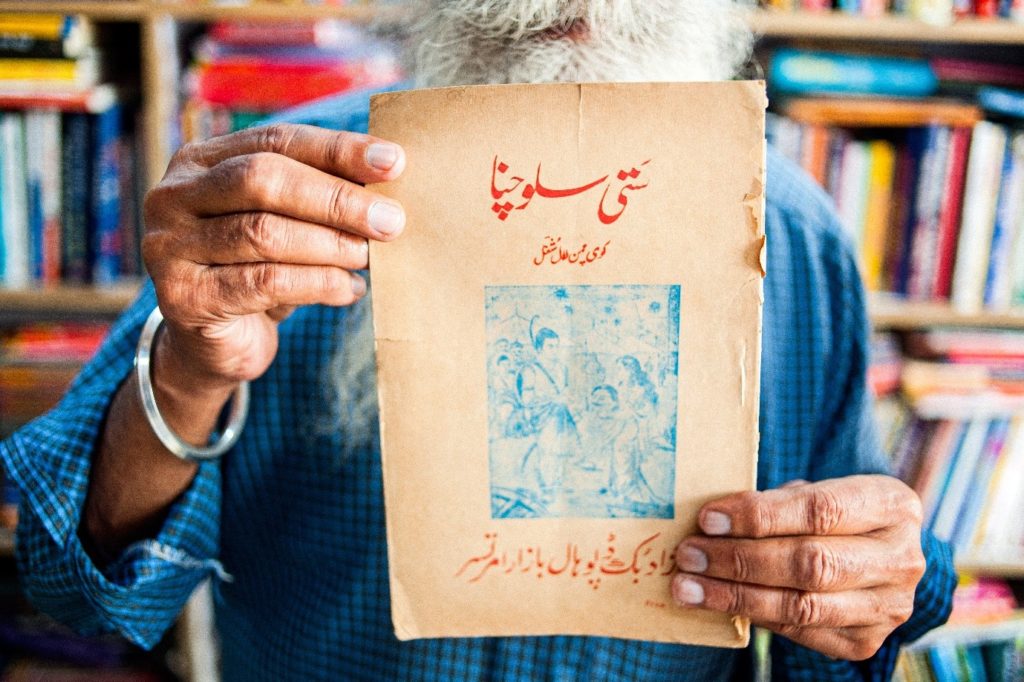

However, having left Delhi, I managed to interview 7 people in one day due to a contact I had, which provided me with the momentum I needed to reach my target. The interviewees ranged from esteemed professors and scholars of Urdu, to faculty staff and students, Hindus and Muslims, native and non-native Urdu speakers. The initial shock and confusion of me turning up at a university department for Urdu slowly turned into genuine interest and joy as I explained my reason for coming and the topic of my research. Immediately someone was sent for chai. Soon around 8-9 of us were sat in the professor’s office, quite informally, chatting away. Having spent the whole afternoon in the offices and corridors of that department under a slowly revolving ceiling-fan, it’s fair to say my brain was pretty overloaded. At the time, and even now, I struggle to believe I was sat reciting famous poems (she’rs) with some of India’s leading academics in Urdu. This provided me with the momentum I needed and more interviews followed with a varied selection of participants, ranging from quite pure-Hindi (shudh) speaking Hindu secondary school teachers, friends I have met during my time in India, friends of friends, a Sikh bookstore owner, to teachers at a madrasa in Uttar Pradesh. This variety of perspectives has been extremely insightful. Undoubtedly, the rise of English in the sub-continent and it being synonymous with being well-educated and a language of the elite was a key reference point. Many also pointed to a neglect of Urdu, particularly in the education system.

My methodology could have certainly been improved by specifying for more informal means of obtaining consent, for example verbal consent which would have been more appropriate for several scenarios I found myself in. Despite this, the pre-arranged, semi-structured interviews that I did carry out went well. Only 2 out of 15 of these interviews were in English however, which often left me unable to fully express myself when wanting to respond in my target language to a sometimes 2 minute monologue about a very complex socio-political topic. I realise now that working with a trusted interpreter would have been beneficial to build on my participants responses.

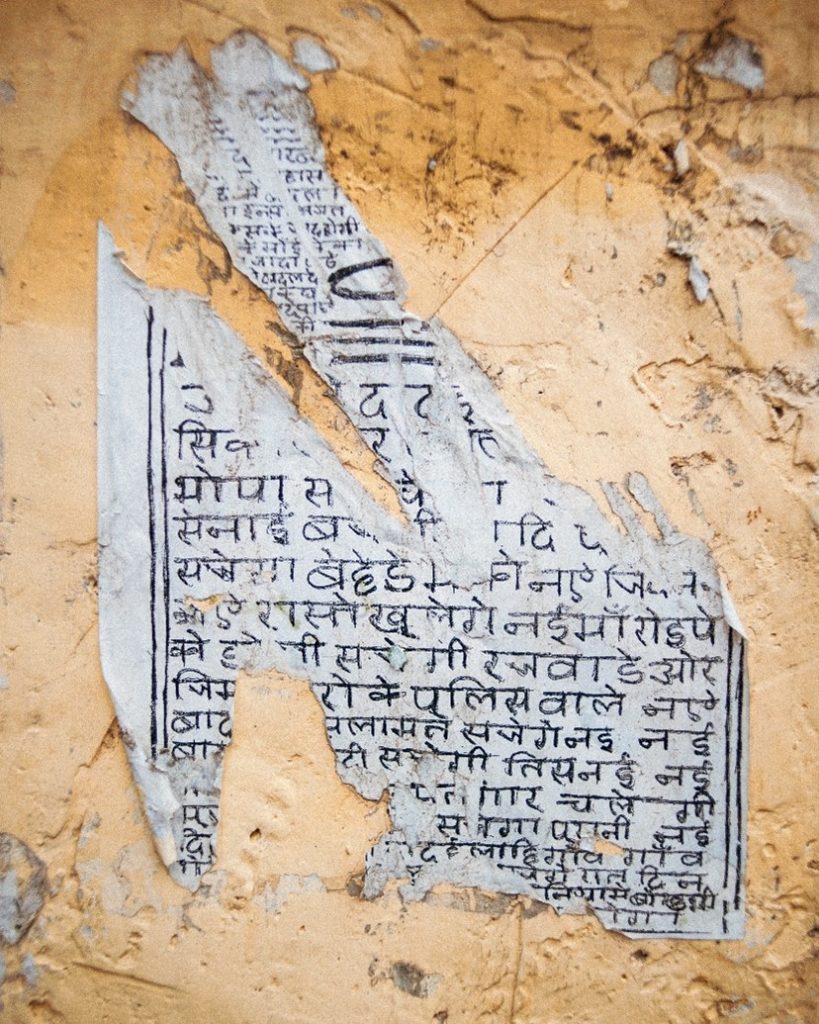

As institutional support for the development of Urdu in India continues to decline, its speakers are left grappling with a cultural landscape which is rapidly changing. My research results are yet to be properly analysed and solid conclusions drawn, and there are certainly worrying trends which I observed. What I can say now for certain, however, is that this trip has highlighted the resilience of the individuals I’ve met who are actively engaged in keeping this language and its linguistic heritage alive, even in the face of rapid technological changes to how language and literature is read and consumed.

I look forward to beginning my thesis and piecing together the interviews I carried out as I come to the end of my time at the University of Sussex.

Very well written piece, buhat khoob!

Thank you.