Written by Sussex alumna, Jamila Travis, (BA International Development 2024)

Food as a means to mobilise against the ‘environmental Nakba’

“What we can do is a small stone in the large mosaic, you add another stone, and we add another one, then we can hopefully complete the whole picture”

(Damir, cited in Simaan, 2017, p. 519)

My most vivid memories of Haifa come in the form of food. Sitting outside one of many Arabic restaurants adorning the road that runs down the slope below the beautiful Bahá’í Temple, lit up at night and shimmering in its full glory. In front of me, a feast for the eyes in the form of labneh, hummus, foul, mujaddara, fattoush, bamieh, warak b’zeit, to name a few. Sitting at a table filled with people drinking, laughing, chatting, and eating, dipping into the huge spread in front of us with fresh, warm flatbread while the sun slowly dips beneath the horizon. The space around us ringing with the echoes of music, and of laughter from other tables – other small communities coming together to share food, to break bread, to talk, and to reconnect. That is what I miss the most.

I myself am not Palestinian. My dad is from Israel; a statement more politically charged than ever since the devastating events on and following October 7th of last year. I often feel the need to follow it up with explanations of his origins and my political standing. His family is not from Israel or Palestine, nor is he Jewish or Arab, but he grew up in Nazareth. When I was 13 he moved back to Israel, after which I would travel twice a year to visit him until the COVID epidemic hit. I have family friends from across Israel, and from a variety of different backgrounds, Palestinian, Jewish, and other. I feel deeply lucky to have grown up with my eyes open to a land filled with so much culture and history. Nevertheless, it is heartbreaking to see how a people whose history, culture, and livelihoods are so wrapped up in the food and land that surrounds them, have been continually removed from both. And yet, I have also seen the many small ways food continues to be a focal point around which seemingly insignificant, yet radical resistance is enacted everyday.

As with so many cultures, food has always been a big part of Palestinian life. Historic Palestine encompassed the land between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, comprising part of the ‘Fertile Crescent’ where agriculture is supported by the mild climate and productive soil close to water, and where historians think the first farming societies emerged (Albert, 1998). The significance of food is not just its importance in sustaining life. Local food and eating habits are tightly linked to the culture, traditions, and identity of Palestinians. An example is the traditions surrounding marriage in Palestinian culture. Weddings are customarily carried out in the summer after harvest, with harvest fields a common venue for the ceremony. The whole community participates, sharing in the expenses and preparation of food and drinks (Shomali, 2002). Similarly, food and agricultural practices are significant in building community and wellness.

Another example is the communal nature of society, often presenting itself through the sharing of food. For example, Abu-A’ttallah and Um-Yasin describe the ancient practice of leaving some fruit on the trees to be picked by local families who are without land (Simaan, 2017). This generosity is clear to all who visit a Palestinian community, as I myself have experienced, having been heartily welcomed by so many families who want to share their homes and food. In this way, the degradation of Palestinian land is not just an act of war, but also a question of cultural and social environmental justice.

Food and Justice

A fundamental aspect of local Palestinian food is the olive, and the cultivation of olive trees that live for hundreds of years, thus being passed down through the generations. Abu-Nedal poignantly reminisces on the nostalgia linked to the olive: “When the first rain came people knew it was olive harvest season. A beautiful season with memories of everyone helping and sharing food” (ibid., p. 517). Few examples thus show the devastating environmental and cultural impacts of occupation as clearly as the olive tree. As of 2020, almost 1 million olive trees in historic Palestine had been damaged or destroyed (Asi, 2020, p. 212), a campaign which has only grown more intense in light of the recent war. This is not only a threat to traditional cuisine and culture, for which the olive tree has become an important symbol, but also hits local livelihoods, as many are dependent upon the income that olive yields bring. However, the impact for communities is far greater than this.

In 2019, a 60-year-old Palestinian woman, Doha, woke up to her olive groves in the West Bank going up in flames. She told The Pulitzer Center, “I could only sit, watch and cry as all my trees burned… My olive trees are older than anyone who is alive today.” As Doha’s comments show, olive trees are an important cultural symbol for many. More broadly, our connection to food, land and environment thus runs far deeper than solely their utility for money and consumption.

Dispossession Through Conservation

The burning of olive groves is only one aspect of a much wider campaign to repossess and destroy Palestinian land in the territories of historic Palestine. In areas designated as nature reserves, Israeli settlers are permitted to destroy native trees and shrubs, and to cultivate the land themselves. Official designations of which areas constitute nature reserves are thus often exaggerated. In 2011, only 3% of the West Bank was labelled part of a nature reserve (Friends of the Earth, 2013), while 12% of it had been declared so by the Israeli state (Isaac and Hilal, 2011). Braverman (2009) highlights how the planting of pine and cypress trees is a strategy often used to create these ‘reserves’. These trees have become a popular symbol of Jewish rootedness in the land. However, they have devastating impacts upon Palestinian agriculture and the environment, since cypresses and pines produce acidic needles that cover the soil and prevent other plants from growing (Weizman, 2007, cited in Panosetti & Roudart, 2023, p. 9).

The Israeli state continues to dispossess rural Palestinian communities under laws that claim all uncultivated and unregistered land as state property. This is done through a land mapping which purports to be ‘neutral’ but can easily be manipulated by selecting aerial photos that display landscapes when seasonal crops and livestock are not present (Braverman, 2008). Thus, in Israel and the occupied territories, the landscapes have been irreparably altered by the settlements built upon such repossessed land. Driving from Jerusalem to Jericho, you can see the striking contrast between the imposing Israeli settlements seated like fortresses on the tops of hills in the mountainous desert, and on the other hand the scattered Palestinian and Bedouin settlements below.

Such means of dispossessing Palestinians from their land simultaneously separate them from methods of food production. This is not just characterised by dispossession but also restrictions on movement and exchange. Under the Oslo Accords the West Bank was divided up into different areas of control, of which the Israeli state was given the majority as well as the entirety of the border, leading to the severe limiting of movement for Palestinians (Friends of the Earth, 2013, p. 7). This has prevented many from crossing borders for work or to sell their produce (Asi, 2020, p. 208). Thus, the Palestinian population has suffered a complete loss of food sovereignty – the right of local peoples to control their own systems of food production and consumption (Wittman, 2011, p. 87).

The ‘Environmental Nakba’

Controls on movement, access and use also applies to water resources. In occupied Palestine, water is redirected to Israeli settlements and Palestinians have little access to local sources, further impacting their ability to cultivate food, as well as their health. This presents immense environmental concerns in terms of the fast depletion of water from local water sources as well as the high amounts of pollution, having devastating impacts on the seas, rivers, and springs of this holy and historically biodiverse land. The crisis is clearly visible in the depletion of water in the Sea of Galilee and the Jordan River, both being integral parts of the landscape. My most vivid memory from my first visit to the area at the age of 5 is the beautiful streams at the Tel Dan Nature Reserve in Upper Galilee that led into the Jordan River. When I returned as a teenager, however, there was little water left, and the dried-up land left the impression of something once beautiful that had now been lost.

These issues are compounded by ongoing pollution. ‘Friends of the Earth’ find that Israel routinely dumps waste and raw sewage into the Occupied Territories, poisoning water supplies, whilst also enforcing restrictions that prevent Palestinian communities from developing adequate wastewater treatment systems. According to Al Jazeera, Israeli settlements are usually built on hills, meaning their wastewater can – and often does – leak into Palestinian villages below, contaminating water supplies, but also polluting cultivated land. Palestinian farmers near settlements have reported poor yield and crop quality, as well as the loss of livestock that have drunk the wastewater.

In this sense, some areas of historic Palestine have become sacrifice zones, areas from which continuous extraction occurs in order to provide resources to another. Water is one example of this, being funnelled away from Palestinian lands and villages that are left thirsty, in order to provide for the new settlements and cities. Thus, certain land, bodies, and cultures are sacrificed to the benefit of others. This extraction has manifested in many ways, and has over the years culminated in the ongoing slow violence that ‘Friends of the Earth’ (2013) refer to as an ‘environmental Nakba’.

Growing Resistance

International aid tends to prioritise short-term needs rather than long-term sovereignty. Asi (2020) highlights that most international funds go towards tangible food goods rather than investment in mechanisms for food production, keeping local communities reliant on aid and trapping them in a system of economic dependency. Furthermore, while this might provide much needed ‘food security’ (ensuring people have access to sufficient and nutritious food (Wittman, 2011, p. 91), it doesn’t replace the role of food production in cultural life. While the building of food sovereignty in Palestine may appear an unthinkable task in the context of continued occupation and brutality, the many examples of ‘agro-resistance’ that have been enacted over the years provide lessons for movements across the world.

Al Jazeera talks about ‘guerilla gardening’ as a popular means of enacting non-violent resistance in Palestine, planting trees to combat illegal land-grabs and reclaim pockets of neglected terrain. Olive tree planting has become a vital component of everyday agricultural resistance, and indeed a broader cultural symbol of Palestinian resistance. They are considered the most effective way of preventing state possession of land through the land-mapping described above, appearing on photos where seasonal field crops and animals may not (Panosetti & Roudart, 2023). They also grow with little labour, while olive oil can be sold on domestic markets, avoiding export restrictions.

This type of resistance is referred to by Simaan (2017) as an example of ‘Sumud’ (ﺻﻣود), meaning ‘steadfastness’, describing actions and values through which people persevere and hold on to their land, communities and culture. Simaan gives the example of when she helped a family plant 500 olive saplings that were uprooted a few days later. However, the next year they planted more trees, determined to continue until their opponents gave up. The trees were still there when Simaan revisited later that year (ibid.). A wide range of agricultural activities have been carried out across Palestine in the name of resistance and food sovereignty. Organisations like the Union of Agricultural Work Committees help Gazans capture rooftop rainwater to counteract water shortages and teach residents to cultivate gardens in their homes to reduce food-spending (Salah, 2018 cited in Asi, 2020). Meanwhile, food cooperatives like the Ma’an (‘together’) Permaculture Center grow food for local populations (ibid.). This variety of everyday forms of resistance provide many an important sense of hope, showing that even seemingly small actions can have big impacts.

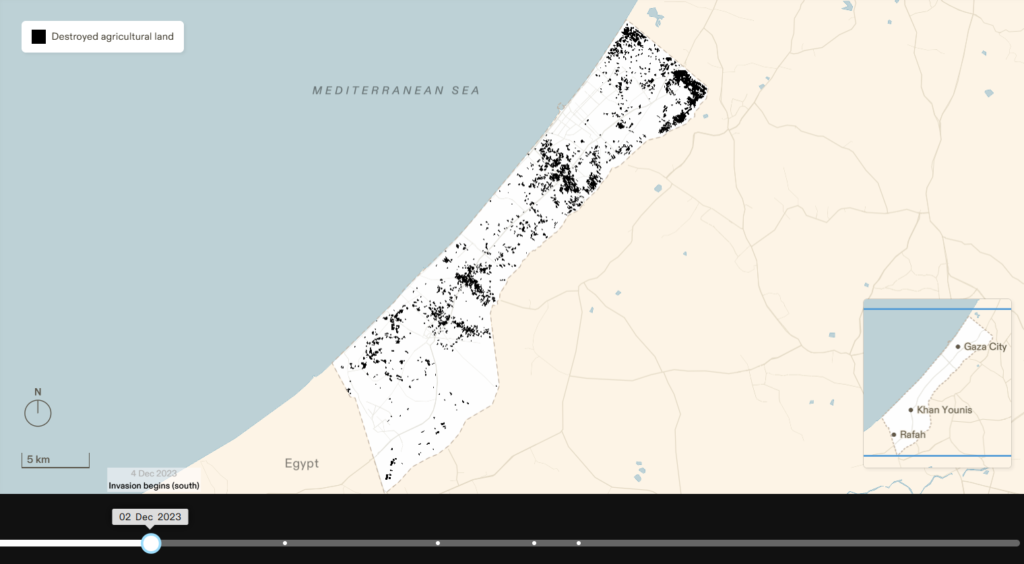

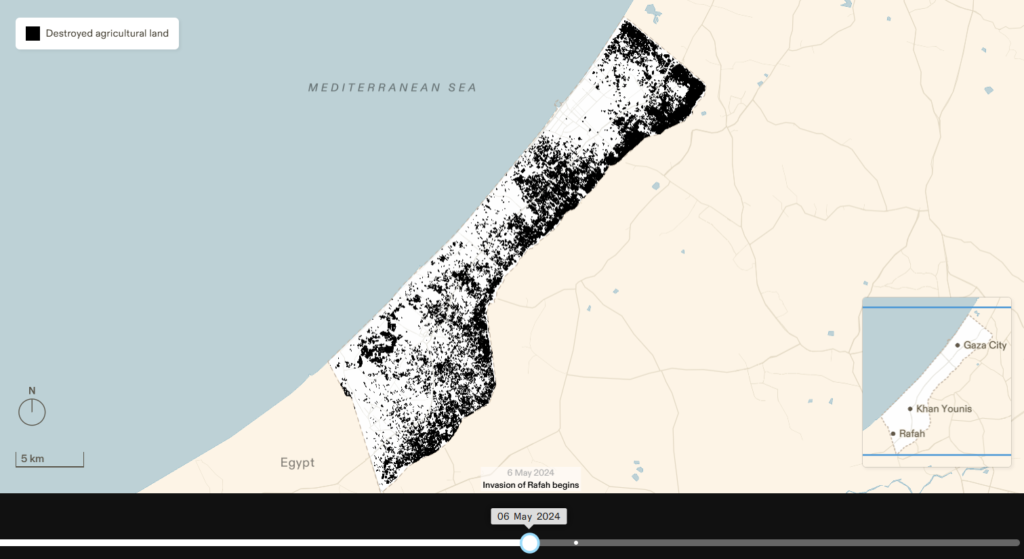

However, this spark of hope has diminished for many in light of the conditions in the current conflict. According to the UN, by January 2024 Gazans already made up 80% of all people facing famine or catastrophic hunger worldwide. Additionally, while all Gazans have faced some level of food insecurity, the UN now also estimates that 16% of the entire population will face Phase 5, or catastrophic, food insecurity, with 70% of crop fields having been destroyed. Thus, not only has the level of food sovereignty violently decreased with the destruction of land, but short-term food security has itself become incredibly scarce. This is because Israeli forces have been blocking aid from entering the occupied territories, to the extent that Joyce Msuya, the acting Under-Secretary General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator for the UN, reported that absolutely no food was able to enter Gaza from the 2nd to the 15th October, and she warned there is now barely any food left to distribute.

In these conditions, it is unrealistic to look to agro-resistance as the way out of the current situation, but without an understanding of the importance of food we miss a critical aspect of cultural erasure in warfare. This is central to the Palestinian experience, both within historic Palestine and among the diaspora, as is the importance of cultural resurgence and resistance against this form of erasure. In addition to the land, food culture is itself a target of settler repossession. Arabic food sign-posted as ‘Israeli’ tabbouleh, ‘Israeli’ falafel, or ‘Israeli’ arak may seem odd to someone who has grown up eating these delicious dishes, but food and cultural appropriation has played an important role in the ‘return’ of Jewish populations from different backgrounds and cultures to biblical Israel. In this context, retaining, sharing, and discussing food culture is not just nostalgic but also deeply political.

Food as Memory

Stam and Shohat (1994) find that the counter-act to appropriation is for writers, poets, and filmmakers to create texts of their own history. One way this can be done in the realm of food is through cookbooks and food writing. In ‘Palestine Writes’, Anderson gives the example of Assil, who owns a Palestinian restaurant and bakery in San Francisco. “For me, being Palestinian, my food is a political identity. I’m very intentional about calling my food Palestinian because we’re at a point in history in which there’s an intentional erasure, a severing of people from their food ways…” There are now a number of Palestinian cookbooks, certainly more than existed in the past. My own well-worn copy of ‘Zaitoun’ (زﯾﺗون) – ‘olive’ – contains the recipes for all of my favourite Arabic meals, wrapped in a beautiful illustrative cover with flowers, citrus fruits, and pomegranates.

Food provides a unique vehicle for remembering. Transporting displaced people back to their homes and families. This provides more than just nostalgia – it provides hope. By preserving the heritage of Palestine, the dream of returning to one’s land, food, and family is kept alive, and this in turn keeps people determined to fight, sparking other forms of radical activism. The first time my family cooked Palestinian food was with some friends we met at a local community garden, who are refugees from Palestine. Together, we cooked flatbreads, mujaddara, fattoush, and foul. While I’m sure our attempts at these traditional meals were far below the standard they would have been used to growing up, even the semblance of their childhood meals was emotional for them. They had not eaten those dishes in years, nor had they seen their families or mothers who used to cook it for them, who are all still in Gaza today.

Food is also a powerful agent in bringing people together in discussion and in community. It can help people connect, tear down walls, and sometimes it is the start of uncomfortable conversations. While food cannot replace other forms of activism, it can help engender awareness, recognition, and healing. Contrary to how it may seem, this is more important than ever in the context of the current war. Palestinians across the world are facing the draining psychological impacts of the occupation. In The Guardian, Bauck cites Laila El-Haddad, co-author of the 2013 cookbook The Gaza Kitchen, who says the more she wrote about guns the more jaded she became. She argues the importance of food in showing the beauty of Palestinian culture, telling the story in a different way. In the same article, Wafa Shami, the food photographer and recipe developer behind ‘Palestine in a Dish’, similarly says:

I just want to show off the beauty of Palestine, the humanity, the culture, away from the politics. Images in the mainstream media here basically show Palestinians as evil, angry, throwing stones or burning tires. But Palestinians are so much more – our art, our music, our food.

Shami discusses the hesitancy she has had sharing food imagery at a time when many face starvation, but how she has been ‘moved to happy tears’ by how many people have tagged her in pictures of the Palestinian food her recipes have taught them to cook. “When you share a meal with somebody, you are connected on a deeper level. We have a saying back home that goes something like, ‘I’m connected to that person because we broke bread together’” (ibid.).

Cooking is a vital way to connect culture and community, and for me it is an opportunity to reflect on what I have left behind in Haifa. Even more so, it has opened up a new world of activism that I did not know before. I spent a beautiful day in April putting my newly acquired cooking skills to the test in the shed of a local community garden, where I and a few other women spent the day cooking mujaddara, labneh, hummus, falafel, tabbouleh, and tahini from scratch, using organic produce they had grown. All funds were donated directly to the Union of Agricultural Work Committee in Palestine. This would support their seed-sharing programme, helping to give people in Palestine access to food now, whilst offering hope for planting projects in the long-term. I was moved that day by the sight of so many people gathering outside to eat together, talk, and open their minds in support of such an important cause. Breaking bread, sharing stories, and remembering may not offer solutions to our global crises – but there are certainly worse places to start.

This blog was written as part of the third-year International Development module ‘Political Ecology and Environmental Justice’

Bibliography:

Albert, J, et al. (1998) ‘Biodiversity and Sustainable Agriculture in the Fertile Crescent’, Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies Bulletin Series, 103(98), pp. 31-57. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_fes_bulletin/98

Asi, Y. (2020) ‘Achieving Food Security Through Localisation, Not Aid: “De-development” and Food Sovereignty in the Palestinian Territories’, Journal of Peacebuilding & Development, 15(2), pp. 205-218. Doi: 10.1177/1542316620918555.

Braverman, I. (2008) ‘‘The Tree Is the Enemy Soldier’: A Sociolegal Making of War Landscapes in the Occupied West Bank.’ Law & Society Review, 42(3), pp. 449–482. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29734134

Braverman, I. (2009) Planted Flags: Trees, Land and Law in Israel/Palestine. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Friends of the Earth International. (2013) Environmental Nakba: Environmental injustice and violations of the Israeli occupation of Palestine: A report of the Friends of the Earth International observer mission to the West Bank. https://www.foei.org/publication/environmental-nakba-environmental-injustice-and-vio lations-of-the-israeli-occupation-of-palestine/

Forensic Architecture. (2024) ‘No Traces of Life’: Israel’s Ecocide in Gaza 2023-2024. https://forensic-architecture.org/investigation/ecocide-in-gaza

Isaac, J & Hilal, J. (2011). ‘Palestinian landscape and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict’, International Journal of Environmental Studies, 68(4), pp. 413-429. Doi: 10.1080/00207233.2011.582700.

Massad, S & Hmidat, M. (2016) ‘Farming, Water, Food Sovereignty, and Nutrition in Occupied Palestinian Territories’, International Journal of Food and Nutritional Science, 3(5), pp. 1-13. https://doi.org/10.15436/2377-0619.16.932

Panosetti, F & Roudart, L. (2023) ‘Land Struggle and Palestinian farmers’ livelihoods in the West Bank: between de-agrarianization and anti-colonial resistance’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, (November 10), pp. 1-23. Doi: 10.1080/03066150.2023.2277748.

Red Nation. (2021) The Red Deal: Indigenous action to save our Earth – Part III: Heal Our Planet. The Red Nation[Online]. http://therednation.org/environmental-justice/

Shomali, M. (2002) ‘Land, Heritage and Identity of the Palestinian People’, Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics, and Culture, 8(4). https://www.pij.org/articles/804/land-heritage-and-identity-of-the-palestinian-people

Simaan, J. (2017) ‘Olive growing in Palestine: A decolonial ethnographic study of collective daily-forms-of-resistance’, Journal of Occupational Science, 24(4), pp. 510-523. Doi: 10.1080/14427591.2017.1378119.

Stam, R and Shohat, E. (1994) ‘Contested Histories: Eurocentrism, Multiculturalism, and the Media’. In Goldberg, D (Ed.), Multiculturalism: A Critical Reader. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wittman, H. (2011) ‘Food Sovereignty: A New Rights Framework for Food and Nature?’,

Environment and Society, (December 2011). Doi: 10.3167/ares.2011.020106.

Really touching read. I love how the blog shows food isn’t just about eating – it’s about memory, culture and resistance. Makes me appreciate how powerful sharing a meal can be.