Written by Gabriel Cavalcante

MA Environment, Development and Policy

University of Sussex

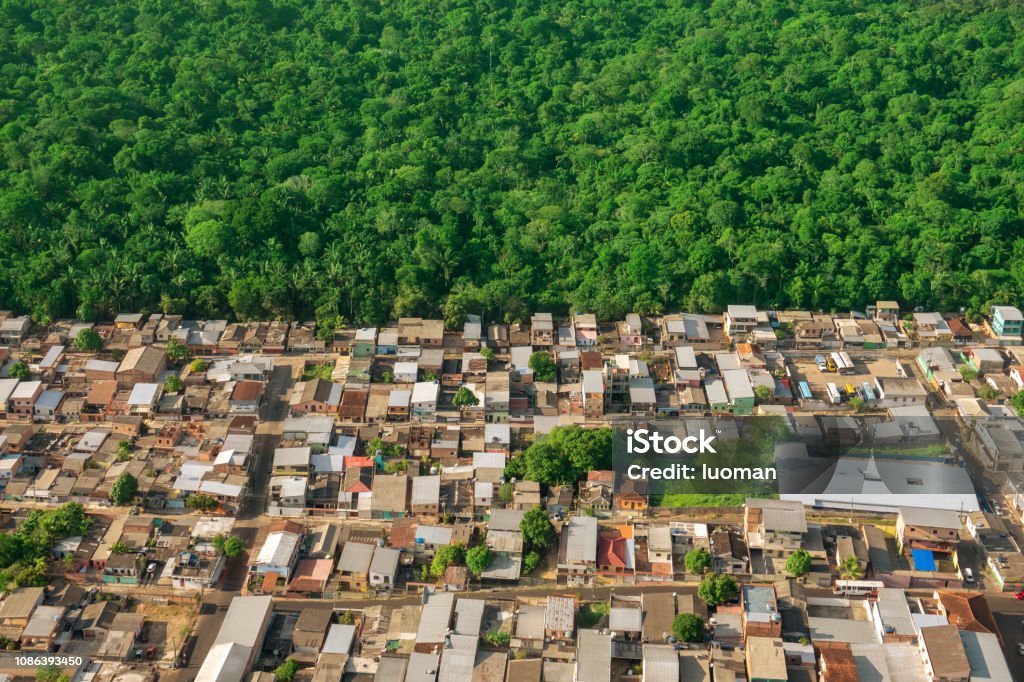

The global view of the Amazon is often limited to its vast rainforest, seen as the ‘sanctuary of biodiversity’. This narrative ignores one fact: the Amazon is also urban. Data released by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) at the beginning of November shed light on this reality. According to the 2022 Demographic Census, the Legal Amazon is inhabited by 27.8 million people, representing 13.7 per cent of the Brazilian population.

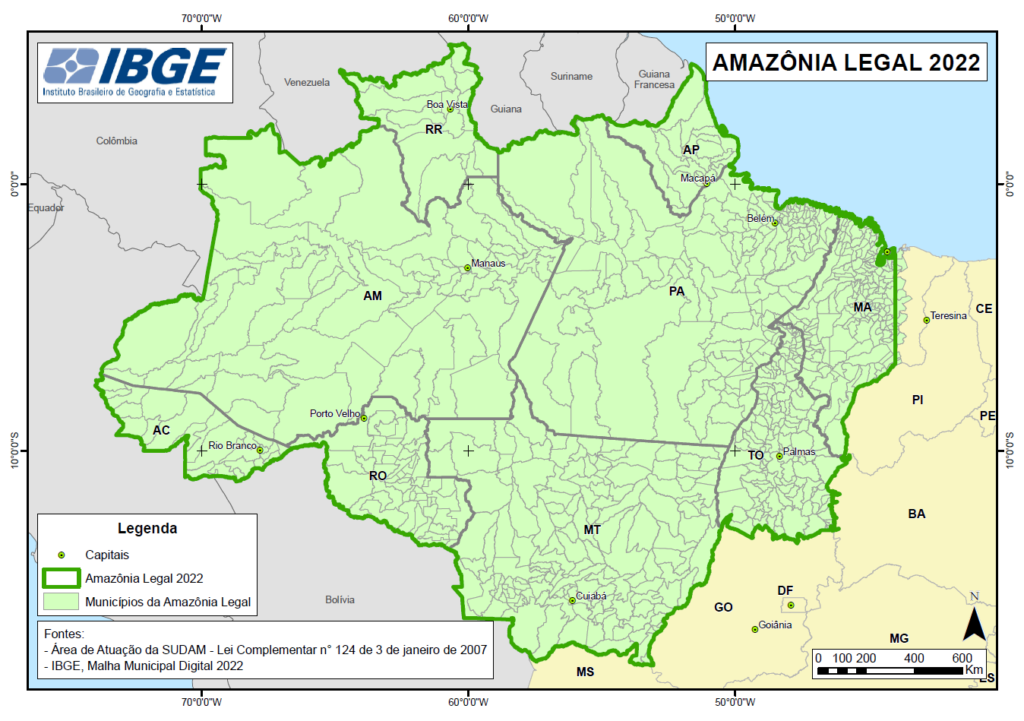

To put this into context, the Legal Amazon covers all the states of the Northern Region – Acre, Amapá, Amazonas, Pará, Rondônia, Roraima and Tocantins – as well as parts of Maranhão and Mato Grosso. As the map below shows:

According to the latest Census, the North Region has 19 per cent of the Brazilian population living in slums, the highest proportion in the country. And its two largest capitals (population-wise) reflect this reality: Belém, which will host COP 30 next year, leads the way with 57.2 per cent of the population living in slums, followed by Manaus, with 55.8 per cent. These are the only Brazilian capitals where more than half the population lives in urban communities. The region is also home to 8 of the country’s 20 largest favelas – 7 of them in Manaus alone.

This is the portrait of a Brazil without an urbanisation plan, without universal water collection and sewage treatment and without protection of its biomes. The data above is the latest evidence that there is an urgent need for a territorial development plan for the north of the country, whose fragility exposes the population to crime, basic sanitation and urban mobility (the latter two non-existent) and the environment to degradation. Any effort to conserve the Amazon must necessarily consider its urban fabric. Neglecting this dimension is tantamount to jeopardising any cooperation for the conservation of the Amazon, which I’ll explain below.

The urbanisation of the Legal Amazon is a direct reflection of the historical strategies of territorial occupation and economic exploitation adopted in Brazil. This process can be divided into two historical milestones: 1) the Rubber Cycle and 2) the Age of Roads and ‘Greater Brazil’. Both were marked by policies that prioritised national integration and the exploitation of natural resources.

1st Historical Landmark: The Rubber Cycle

The rubber cycle was a historical period in Brazil, between the late 19th and early 20th centuries, marked by the intense exploitation of latex extracted from the rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis), a tree native to the Amazon rainforest. This latex was transformed into rubber, a valuable product at the time and widely exported to meet the growing global demand of the Industrial Revolution, especially in the automobile and war sectors (Weinstein, B., 1983).

Cities like Manaus and Belém prospered economically, attracting immigrants, foreign investment and modern infrastructure. Manaus, for example, was the first Brazilian city to have public electricity and even imported materials from Europe to build the iconic Amazonas Theatre (Becker, 1990).

However, this urban expansion was elitist and deeply unequal. The wealth generated by rubber benefited the few, while the majority of the population lived in precarious conditions, without access to infrastructure or basic services. Furthermore, with the collapse of the rubber cycle at the beginning of the 20th century, these cities faced economic stagnation, creating a fragile urbanisation base dependent on external economic cycles (Chein, 2022).

2nd historical milestone: the era of motorways and ‘Brasil Grande’ (Big Brazil)

In the 1970s, during the military regime, the Amazon became the centrepiece of a national development project known as ‘Big Brazil’. This period was marked by major infrastructure projects, such as the opening of motorways (BR-364 and Transamazônica), tax incentives for agriculture and mining, and the construction of hydroelectric dams. These initiatives aimed to integrate the Amazon with the rest of the country and consolidate Brazilian sovereignty over the region (Fajardo et al., 2023).

Cities grew rapidly along these roads, often without proper planning. Small villages became improvised urban agglomerations to meet the demand of workers attracted by these projects. The occupation logic was predatory: the forest was seen as an obstacle to be overcome, and the urban settlements were conceived as support points for the exploitation of resources. As a result, cities like Altamira, Marabá and Porto Velho grew, but with insufficient infrastructure and high dependence on local economic activities, such as mining and cattle ranching (Chein, 2022).

OK, but what were the results of these actions?

Both historical moments left a legacy of inequality and precariousness in Amazonian cities. Only half of the municipalities in the Legal Amazon have a Master Plan, the basic urban planning instrument, and many of these plans are out of date. Cities face problems such as lack of basic sanitation, limited access to public services and high socioeconomic vulnerability (Fajardo et al., 2023).

Furthermore, the integration of cities into the Amazon ecosystem has historically been neglected. By treating the forest as an obstacle to progress, urbanisation projects have ignored the importance of solutions adapted to the Amazonian context, such as valuing hydrography for transport and sustainable urban planning. The result is fragmented urbanisation, marked by deep inequalities and severe environmental challenges.

What’s next?

The structural problems faced by Amazonian cities require a profound change in public policies, with a focus on sustainable urban planning, environmental integration and social inclusion. Solutions that combine innovation and sensitivity to the local context are indispensable for overcoming decades of neglect and predatory exploitation. Below, I use three studies to highlight the five main points that must be prioritised in order to guarantee fair territorial development:

- Urban Planning

More than 50 per cent of the municipalities in the Legal Amazon still lack up-to-date Master Plans, which are essential for guiding urban growth in a balanced way (Fajardo et al., 2023). The implementation of plans that integrate housing, transport and environmental preservation is urgent to avoid the perpetuation of inequalities and environmental damage within Amazonian cities.

- Basic sanitation

The lack of basic sanitation is one of the biggest indicators of exclusion in the region. According to Cynamon et al. (2007), intersectoral policies that align infrastructure and health are crucial to promoting quality of life and reducing health and environmental risks.

- Amazon Hydrography as an Axis of Mobility and Planning

Chein (2022) argues that Amazonian rivers, essential for transport and local life, remain underutilised in urban planning. Incorporating them as axes of mobility and integration is a sustainable solution that respects the geographical dynamics of the region.

- Inclusive Housing

The concepts of habitability and ambience, as highlighted by Cynamon et al. (2007), are fundamental to rethinking housing development in the Amazon and in other contexts of vulnerability. These concepts transcend the idea of housing as a mere physical space, considering it as an element integrated with human well-being, public health and environmental balance.

- Social Participation

Fajardo et al. (2023) argue that the active inclusion of communities in urban planning is essential to ensure that the solutions implemented reflect the local and specific needs of the Amazonian population. By integrating local voices into the decision-making processes and construction of public policies for cities, it is possible to build a relationship of co-responsibility, where communities not only influence the guidelines, but also contribute to their implementation and monitoring.

Almost over…

On 24 November, COP-29 in Baku ended with results that fell short of expectations, especially with regard to financial commitments to tackle the climate emergency. This scenario imposes a huge challenge on Belém, which will host COP-30 in November next year, demanding significant efforts and Brazilian diplomacy to match the circumstances.

Holding the event in a capital city where 57.2 per cent of the population lives in slums highlights a glaring paradox. How can climate justice be debated in a city that symbolises the structural abandonment of the city, its population and the environment?

By imposing COP-30 in Belém, without a robust legacy plan for the city and its population, the Brazilian government risks turning the event into a spectacle disconnected from local reality. Without concrete actions to tackle inequalities and promote sustainable urban development, COP-30 risks being just another stage for empty promises, rather than catalysing real change.

As an Amazonian Brazilian, I’m sad to write this.

But we continue to resist.

REFERENCES

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). (2022). 2022 Demographic Census: Brazil had 16.4 million people living in favelas and urban communities. Available at: https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/

- Cynamon, S. C., Bodstein, R., Kligerman, D. C., & Marcondes, W. B. (2007). Healthy housing and healthy environments as a strategy for health promotion. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 12(1), 191-198. Available at: https://www.scielo.br/j/csc/

- Fajardo, P. C., Santos, A. M., & Neves, M. C. (2023). Amazonian Cities: A Call to Action. Publication on urban planning and action for the Amazon Legal region.

- Chein, J. S. (2022). Cities in the Amazon Legal Region. Study on urbanization in the Amazon.

- Becker, B. K. (1990). Amazonia: Geopolitics at the Turn of the Third Millennium. Brazilian Journal of Geography.

- Weinstein, B. (1983). The Amazon Rubber Boom, 1850–1920. Stanford University Press.

Leave a Reply