Written by Gabriel Cavalcante (MA Environment, Development and Policy)

The expansion of livestock farming in the Brazilian Amazon has transformed one of the world’s most crucial ecosystems into a global beef supplier. This economic growth has come with significant environmental and social costs, as livestock farming remains a principal driver of deforestation, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions in the region. This article examines the political economy of livestock expansion in the Amazon through the lens of Degrowth theory.

Global demand and government incentives have driven the expansion of this sector, making Brazil one of the largest greenhouse gas emitters due to deforestation in the region. This growth model has far-reaching consequences: it not only accelerates environmental degradation but also threatens Indigenous land rights and displaces rural communities. By examining these dynamics, we can explore how Degrowth theory challenges the prioritisation of economic expansion at all costs, offering alternative models that centre on ecological conservation and social equity.

The Amazonian livestock industry is significantly shaped by the global neoliberal model, which promotes GDP growth as an ultimate benchmark of progress. Global demand for beef—primarily from Global North nations—drives large-scale cattle production in the Amazon, incentivizing extensive deforestation to create pastures for livestock. In 2023, Brazil exported a record 2.29 million tons of beef to 157 countries across all continents, reinforcing its position as a major global supplier (ABIEC, 2024). This demand is underpinned by a complex web of international trade agreements and corporate interests that prioritise low-cost production. The ongoing trend of resource extraction from developing regions, historically rooted in colonial exploitation, persists under globalisation. This dynamic enables wealth accumulation and consumption in developed nations while imposing ecological burdens on regions like the Amazon, which serves to supply commodities such as beef to the global market.

The resulting dynamic pressures Brazil to cater to these markets by scaling up livestock output, often at the expense of its environmental commitments. These policies and practices reflect a broader failure to recognize the ecological cost of this model, where the value of ecosystems is reduced to their immediate economic outputs rather than their role in sustaining life and climate stability. This paradigm supports the intensive exploitation of natural resources, often with little regard for the ecological degradation and social inequities it incurs. As Sullivan (2009) critiques, this capitalist approach treats environmental crises as opportunities for profit, where ecosystems are commodified for market gains, despite the long-term harm inflicted on both biodiversity and the communities that depend on these lands.

The expansion of livestock in the Amazon is evident, with states like Pará and Rondônia showing significant increases in herd size—Pará saw an 8.1% growth between 2013 and 2023, while Rondônia reached approximately 13.8 million heads in 2023 (ABIEC, 2024). This expansion shows that more areas are being converted into pastures, a process often associated with deforestation in the Amazon. According to Amazônia 2030, over 65% of deforested land in the Amazon is now dedicated to low-efficiency pastures, supporting fewer than one head of cattle per hectare. Moreover, in major livestock-producing states such as Mato Grosso, Pará, and Rondônia, around 30% of Brazil’s national cattle herd is concentrated within the Amazon biome (A Concertation for Amazon, 2020). The environmental impacts of this expansion are profound. Deforestation linked to livestock farming has positioned the Amazon as the largest emitter of greenhouse gases in Brazil. In 2022, deforestation accounted for 97% of Brazil’s total gross emissions, reaching 1.081 billion tons of CO2e. of these emissions from deforestation, 75% (837 million tons) originated from the Amazon (SEEG, 2023).

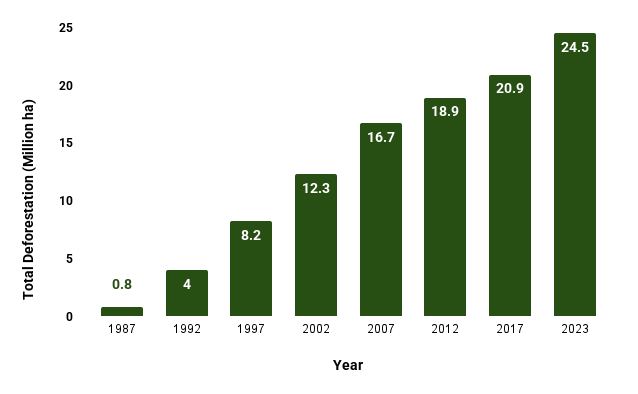

Figure 1: Annual Total Deforestation in the Amazon (1987–2023)

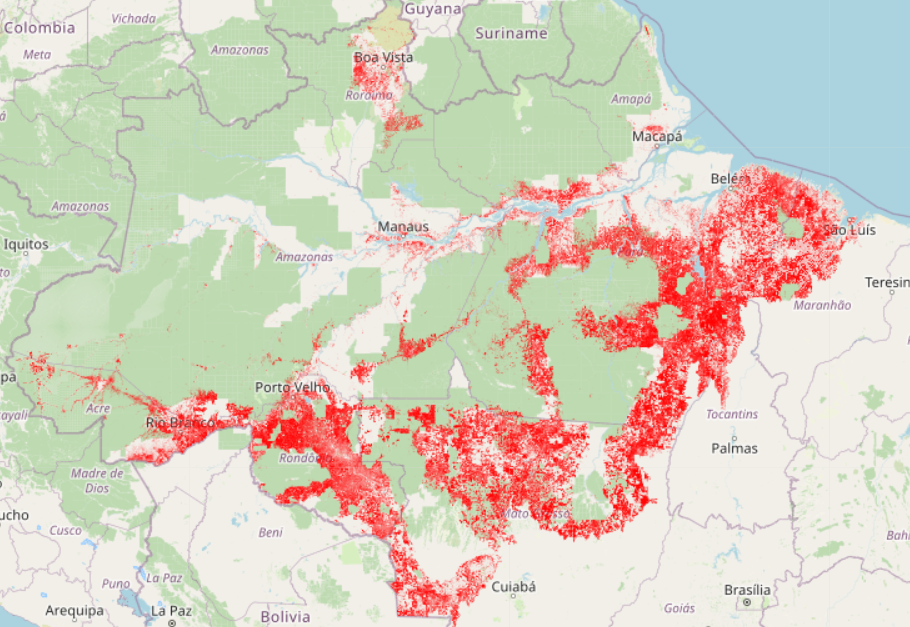

Figure 2: Accumulated Deforestation in the Amazon (1986–2023)

The government of Brazil, historically incentives for agribusiness, with subsidies, tax breaks, and favourable land-use policies for large agricultural corporations create a growth-friendly environment that overlooks forest. While the concept of “green growth” is often promoted as a middle ground—suggesting that economic growth and environmental preservation can coexist—these policies reveal a fundamental contradiction. As Jacobs (2013) argues, the green growth model, while claiming to align economic expansion with environmental care, often serves as a rhetorical device to justify continued exploitation under the guise of “sustainability”. Policies like REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation), promoted by the Brazilian government under the guise of sustainable development, aim to create financial incentives for forest conservation by monetizing carbon sequestration. However, these approaches often reduce forests merely to their carbon storage potential, overlooking broader ecological and social values while failing to address the root causes of deforestation (Humphreys, 2013). Humphreys argues that although REDD recognizes the public good nature of forests, it still prioritises economic metrics over the preservation of complex ecosystems. This lack of enforcement allows agribusinesses to operate with near impunity, thereby advancing growth in a way that prioritises economic gains over ecological limits.

This political economy is also marked by a disregard for the local and Indigenous populations affected by livestock expansion. Indigenous territories and protected lands are increasingly threatened by encroachment, as the push for cattle production reshapes land use across the Amazon. As Sullivan (2009) underscores, this “crisis capitalism” exploits not only the land but also the labour and livelihoods of local communities, leading to displacement and the disruption of cultural ties to the land. The prioritisation of export-driven livestock production manifests in an inequitable distribution of benefits, where profits are funnelled to large agribusinesses while the environmental and social costs are borne by local communities. Moreover, this approach disregards the ecological value of the Amazon as a carbon sink, which is crucial for mitigating climate change globally.

Hickel and Kallis (2020) argue that the Degrowth framework underscores the incompatibility of continuous economic expansion with the ecological limits of our planet, advocating for a shift from growth-centred policies to ones prioritising ecological and social well-being. From this perspective, the Amazon’s role should transition from a production zone to a preserved ecosystem, where the forest’s value is derived not from its capacity for cattle grazing but from its ecological functions and cultural significance. Degrowth proponents call for reducing dependency on global markets that exploit natural resources, advocating instead for local economies that respect ecological boundaries and prioritise community well-being.

An analysis of livestock farming in the Amazon reveals that, although its expansion is promoted as an economic strategy, it has not yielded significant development gains for the region. Productivity remains low, characterised by suboptimal land use and limited employment and income generation. Data shows that less than one-third of the potential production capacity is utilised, making the current model unsustainable both environmentally and economically (Barreto, 2021).

Degraded pastures present a further challenge, the study notes that 59% of pastures in Brazil are degraded, affecting profitability. Restoring these areas requires investments that many rural landowners either cannot or choose not to make, given the abundance of land and economic incentives for deforestation. Rather than reinvesting in the land, owners often opt to clear new areas, perpetuating a cycle of degradation and expansion that fails to foster economic progress for local populations. This is reflected in low formalisation rates and lower-than-average earnings for sector workers—34% below regional averages, according to the Amazonia 2030 report.

Livestock expansion also does not significantly improve socioeconomic indicators, such as education, health, and sanitation, which remain precarious in the Amazon. The lack of investment in rural infrastructure, technical assistance, and education limits innovation and productivity improvements, leaving most Amazonian municipalities among the lowest-ranked in these indicators (Barreto, 2021). This reality reinforces that a development model based on pasture expansion fails to deliver the anticipated economic benefits.

The Amazonia 2030 report further highlights that deforestation is unnecessary for economic growth. From 2004 to 2012, as policies reduced deforestation by more than 80%, the Amazon’s agricultural GDP still increased by 45%. This shows that enhancing productivity in already deforested areas could support production without further expansion—a core Degrowth principle, which critiques growth pursued at the environment’s expense. Efforts should focus on improving efficiency and intensifying production within deforested areas, avoiding additional forest destruction.

To reduce deforestation in the Amazon, a multifaceted approach must prioritise sustainable land use, robust monitoring, and local community involvement, aligned with Degrowth principles that advocate for ecological and social prioritisation over relentless economic expansion. According to Barreto (2021), it is crucial to implement public policies that encourage the intensification of livestock practices, ensuring that current agricultural lands are used more efficiently to curb the need for further land clearing. Enforcing the Brazilian Forest Code (Law 12,651/2012), alongside securing land tenure, could help curb illegal expansion and deforestation— an issue due to unclear property rights across 30% of the Amazon. This law establishes protections for native vegetation through Permanent Preservation Areas (APPs) and Legal Reserves on rural lands, aiming to balance sustainable land use with environmental conservation while promoting land tenure regularisation and economic incentives for preservation.

It’s necessary developing comprehensive regional planning that involves traditional and Indigenous populations along with local governments is critical for sustainable management. This recommendation supports Degrowth’s call for decentralising economies and empowering local governance to uphold environmental protection. The promotion of sustainable land use, such as restoring degraded pastures and forest lands, provides a pathway to maintain ecological functions without expansion into untouched areas. Payments for Environmental Services (PES) to Indigenous communities and legal recognition of these territories can strengthen forest conservation, ensuring that these lands contribute to climate regulation and biodiversity conservation. But, without immediate action, the continued exploitation of the Amazon Rainforest for short-term gains risks pushing this critical ecosystem beyond the point of recovery.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A Concertation for Amazon. (2020). Sectorial Overview of Livestock Farming in the Amazon. Available at: here (Accessed: 31st October, 2024).

Amazonia 2030. (2023). Zero Deforestation and Territorial Planning: Foundations for Sustainable Development in the Amazon. Available at: here Accessed: (Accessed: 30th October, 2024).

Barreto, P. (2021). Policies to develop livestock in the Amazon without deforestation. [e-book] Available at: here (Accessed: 30th October, 2024).

Barreto, P., et al. (2023). The Meat Production Chain Continues to Contribute to Deforestation in the Amazon [e-book]. Belém, PA: Amazon Institute of People and the Environment. Available at: here (Accessed: 30th October, 2024).

Brazil. Law No. 12,651, of May 25, 2012. Provides for the protection of native vegetation, Official Gazette of the Union, Brasília, DF, May 28, 2012. Available at: here (Accessed: 31th October, 2024).

Brazilian Beef Exporters Association (ABIEC). Beef Report 2024. Available at: here (Accessed: 31th October, 2024).

Clapp, J., & Dauvergne, P. (2005). Paths to a Green World: The Political Economy of the Global Environment. The MIT Press.

Hickel, J., & Kallis, G. (2020). Is Green Growth Possible? New Political Economy, 25(4), 469-486. doi: 10.1080/13563467.2019.1598964.

Humphreys, D. (2013). Forest Politics and the Global Climate Regime: Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+). In The Handbook of Global Climate and Environment Policy.

Observatório do Clima. Analysis of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Their Implications for Brazil’s Climate Goals. SEEG, 2023. Available at: here (Accessed: 31th October, 2024).

Sullivan, S. (2009). The Natural Capital Myth, and Other Tales of Conservation, Capital Accumulation, and Scarcity. Radical Anthropology.

Leave a Reply