by International Relations student Sara Monteiro

*The views in the following article are the personal views of the author and are not an official position of the School.*

Basic recipe and main ingredients

Turning any crisis into something profitable usually follows the same basic recipe, with the following main ingredients:

- Discourse

- Media

- Co-option

- Politics

Mix these in a large bowl of International Capitalism, season to taste (more or less authoritarian/democratic/etc.) et voila! A delicious profit cake. Depending on the amounts used, it can serve transnational sized classes.

The CO 2 question as a practical example:

1. Global CO 2 emissions are too high due to the growing industrialization of the ‘underdeveloped’ countries

2. Campaigns for a sustainable economy, advertisement of Eastern countries emissions in comparison to the West, etc

3. Partnerships between NGOs and corporations for sustainable businesses.

4. Policies and agreements created to develop a Green Economy

Decoding the recipe

Ingredient no 1: Discourse

A specifically constructed narrative is essential in drawing the desired scenario, which usually consists in a partial truth flavored with a biased interpretation of it. Example:

● CO 2 emissions are too high – true

● Due to the growing industrialization of the ‘underdeveloped’ countries – limited analysis that doesn’t consider either the retroactive effects of the high levels of industrialization in the Global North, nor the growing emissions of Western industries located in countries of the Global South

Ingredient no 2: Media

A focused approach on the part of the Mass Media is key in spreading that specific narrative. Said scenario is then normalized through a re-framing of the problem in a unilateral way, hiding the other sides of the matter. Example:

● Green economy implies that a capitalist system can be sustainable, although capitalism is, by definition, unsustainable, since it aims to indefinite growth and thrives on uneven development

● The total number of CO 2 emissions is a very misleading statistic, since it hides how much of those emissions are due to foreign industries for instance, or how much each citizen is responsible for on average, etc

● As an example, the total values after 2016 were 9839mtCO 2 for China, almost twice as the US 5269mtCO 2. However, the value per capita in China is 7.2mtCO 2, which means that in reality Chinese citizens are responsible for less than half of carbon emissions compared to Americans, which produce 15.5mtCO 2 per person 2

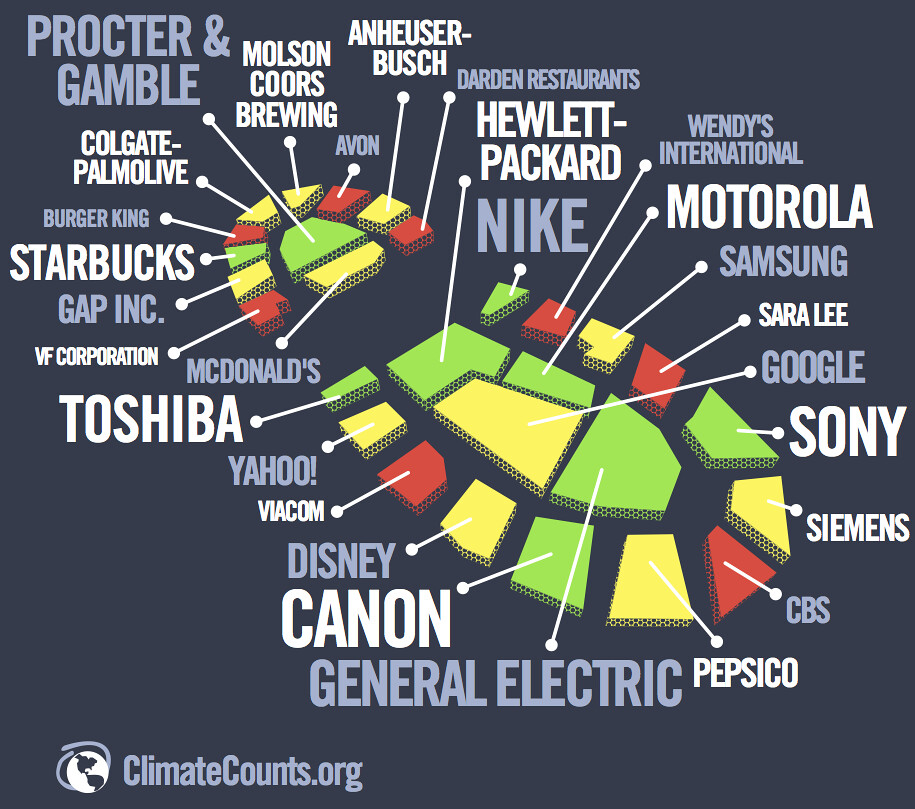

Ingredient no 3: Co-option

In case it’s not clear enough by now, ‘co-option’ here reads as corruption , and refers to when the merging/cooperation between organisations makes possible the pursuit of a given goal without the interference of bodies with conflicting interests. Example:

● Agreements between corporations and conservationist organisations pass the idea of redemption and help mistaking methods of ‘compensation’ of emissions, (like offsetting projects) with the business model / method of production actually becoming greener

● Conservation then becomes a tool for facilitating the usage of land in the Global South to seemingly reduce Global North’s emissions and make impact assessments seem more favorable, when in fact the issue is only being moved around, not solved

Ingredient no 4: Politics

A range of adapted policies provides the practical tools to be used towards achieving a specific goal and thus benefiting a specific group of people. Example:

● Programs such as REDD seem to aim discouraging deforestation 3

● In reality, it targets the final balance associated with a company’s

deforestation/forest degradation, thus incentivising the trading of carbon stocks. In other words, as long as you plant a bunch of trees somewhere else, you’re fine destroying a centenary woodland, or a tropical rainforest and keep growing your business

What makes this possible

This recipe is only possible, of course, within a neoliberal capitalist context, which progressively turned us from a human society into a “market society” 7. A society where capital is prioritized over society itself, and financial markets are more important than a nation’s “real economy” 4 and the quality of life of its citizens.

Commodification of everything

We arrived at such an extreme of capitalism that we commodity – literally – everything 7 . From nature itself – not only raw materials, but land, water and even air – to the most abstract services and/or ‘products’, like our own time and sweat (i.e. labour), and even our body organs!

Normalizing the notion of Nature as a commodity 6 is one of the main contributors to the current environmental crisis. Simultaneously, it helps masking the root causes of this crisis, and gives way to notions such as ‘Green Economy’, which incentivizes the green-washing of businesses and industries rather than the implementation of real solutions, both to the environment and people’s lives.

What about solutions?

Solutions entail primarily a reform of our socio-political system, and only then technological development, as a complement.

As suggested above, the climate crisis and the modern capitalist system are intrinsically connected. What this means is that the most efficient way to solve either climate change and social injustice, is to tackle both at the same time! Models of a Green New Deal developed in the US and UK are thought for that.

Of course, in the long run, the most efficient solution is to find a more cooperative system, based on a local and cooperative economy organized around smaller clusters of people, like the grouping of cells within our body that allow organs to function efficiently and thus take part in sustaining the wider mechanism of our body.

At least for now, a planned transition to a more sustainable lifestyle through an integrated program that takes into account not only the final goal, but also the process of transition itself, would be a good start. For this we have the tools, we just need the will to use them.

References

- Ghosh, I., 2021. All the World’s Carbon Emissions in One Chart. [online] Visual Capitalist. Available at: https://www.visualcapitalist.com/all-the-worlds-carbon-emissions-in-one-chart/ [Accessed 19 October 2020].

- The World Bank, 2021. CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita) | Data. [online] Data.worldbank.org. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.PC?end=2016&name_desc=false&start=2016&view=bar [Accessed 19 October 2020].

- WWF World Wide Fund for Nature; IIASA International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (2015) WWF living forests report: chapter 5. Saving Forests at Risk., Gland: WWF – World Wide Fund for Nature.

- Strange, S. (1998). Mad money. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Watson, M., 2021. Karl Polanyi; The Great Transformation and a new political economy. [online] University of Warwick. Available at: https://warwick.ac.uk/newsandevents/features/polanyi [Accessed 6 November 2020].

- McAfee, K., 1999. Selling Nature to Save It? Biodiversity and Green Developmentalism. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 17(2), pp.133-154.

- Marx, K. ‘The fetishism of the commodity and its secret’ in Marx, Karl, (1976) Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, London: Penguin, pp. 163-177.

Leave a Reply