This post is written by Lizzi Joyner, a first-year undergraduate in International Development, as part of our ‘Experiences in Diversity’ series. She talks about her experiences on ICS in partnership with Tearfund and Zoe-Life in South Africa. She writes at her own blog https://may-we-never-lose-the-wonder.blog/.

South Africa. A nation brimming with beauty and brokenness. A nation surviving the most turbulent times, from colonial oppression to the apartheid, to its aftermath today. Because South Africa is such a meshing of languages (there are currently eleven official languages), races and cultures, its make-up is massively distinctive.

ICS is a UK government-funded programme giving young people the opportunity to explore the world of development in an overseas context. Its structure is brilliant: by building partnerships with grassroot movements in relationship with communities and demonstrated by living in host homes and splitting teams between UK and in-country volunteers.

To say that South Africa is a country of contrasts would be an understatement. According to the GINI Index via the World Bank, it is the most unequal society in the world. Inequality has actually increased since the ending of apartheid, with half of the population living below the poverty line. Shockingly, 1% of the population own 70.9% of the country’s wealth whilst the bottom 60% control just 7% of assets. The unemployment rate is also astoundingly high at 27.1%. These systematic imbalances are seemingly accepted – it’s part and parcel of society.

From my own perspective, I found it inexplicable encountering stark inequalities in varying neighbourhoods. I lived in a township called Chesterville close to Durban, and it was a great community to be in. However, close to our place of work located above a freeway was a shanty town. Tiny houses crafted together of tarpaulin and corrugated iron sheeting were clustered together, with poor local facilities or services available. Yet just a ten-minute drive away, and the story looks a whole lot different. Closer to the Westville area were genuine mansions – complete with perfectly manicured gardens, fleets of cars and probably maids to boot. Inequality is one of the greatest challenges facing this generation as the richer get richer and the poorer get poorer. I can think of no other place this is manifested better than the homes of South Africans.

ICS uses the approach of host homes together with an in-country counterpart within a community setting – one I highly rate. Living in a host home introduced me to a world so unlike my own and it led me to far better understand the surrounding complexities of culture. That said, living in a host home could be incredibly challenging. In a typical South African family (or Zulu culture), it’s incredibly common for extended families to all live together as one. On a given day, there were just under ten of us eating dinner, with a few extra guests often thrown in! We had a very open-door policy (no, quite literally). Yet household tasks tended to fall to the women. On the weekend of our arrival, I vividly remember being asked when we intended to make breakfast for all the family. Instantaneously, I was outraged. But this is the reality for the majority of women. The cooking, the cleaning, the childcare, the washing etc was women’s work. (I did by the way, overcome my frustration but it remained a source of contention!) Communicating across cultures was another interesting one. Our host family were afraid to offend or criticise us as white foreigners, so they voiced their opinions through our team counterparts. This backhanded method of communication was tough, both on ourselves and our counterparts. Being treated differently as the minority was a struggle, but looking back, it transformed my thinking in what it really means to be a minority, especially in the long-term.

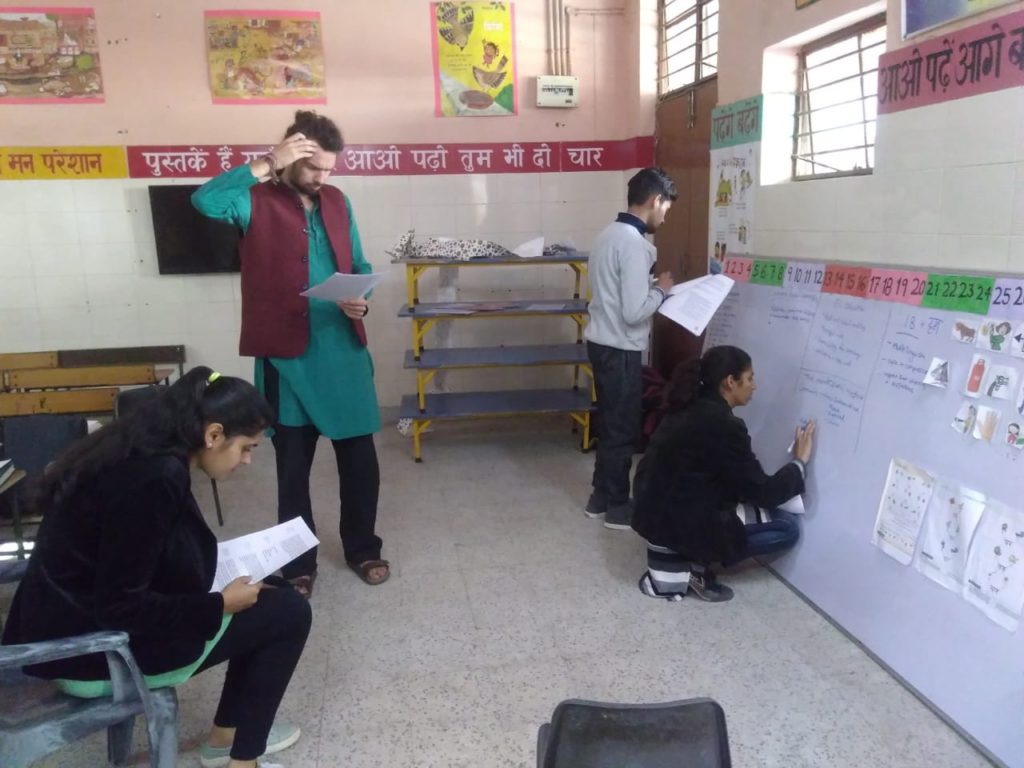

Work-wise, we busied ourselves focusing on education and young people within schools and youth work. This again exemplified massive contrasts of inequality. Whilst working in the schools, under-resourced and wholly black, it was difficult not to imagine the privilege enjoyed in richer areas, predominately white. At first, it was hard to conceal my disapproval for corporal punishment. Yet as I became more tolerant (or possibility patient), I better understood how such conditions made teaching such an enduring career. I found immense respect for the teacher I assisted, and so a genuine relationship blossomed between us. This was also mirrored with fellow team members. It says a lot about how much more ‘development’ can be achieved from the fruition of good working partnerships.

The modern-day expectation seems to be that because official apartheid is over and institutional racism is illegal, the issues of segregation are over. While it is no longer policy, it is certainly embedded into culture as practice. Even decades later, you are categorised into black, white, coloured or Indian groupings. There are some extras, like being a ‘yellow-bone’, meaning you have lighter skin but are neither black nor white. Your race becomes your sole identity: this is who you are. Unfortunately, there’s no allowance for grey areas (pun intended) and consequently, social segregation is all too real. It was rare, near impossible even, to see groups like us merge, be it in the shopping mall or on Durban beach, and we often encountered strange looks and comments from passers-by as we walked the streets.

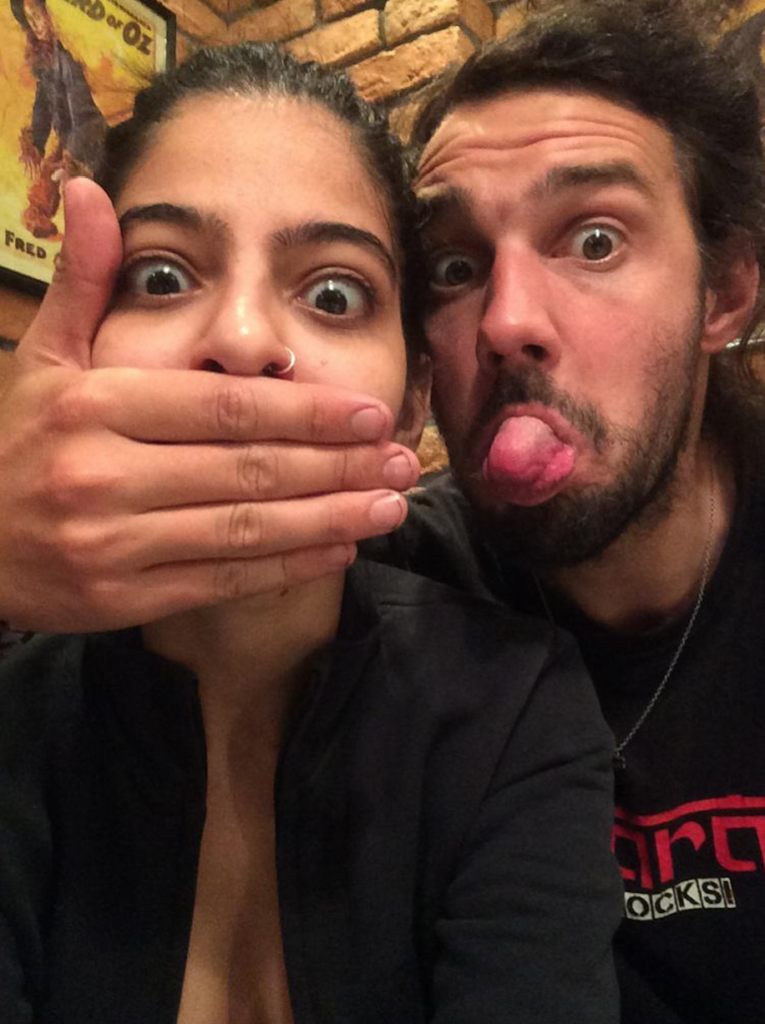

Which leads me onto discussing the best part of ICS: my team. We were a kaleidoscope of characters to say the least; equally split between UK and SA volunteers, male and female plus a UK Team Leader. Living and working with the same nine people day after day in a foreign environment can be intense. It’s super 24/7, and there’s no room to hide tensions. During our pre-departure training, both sets of volunteers were prepped on what to expect from the ‘other’. Sadly, past experiences transpired that SA volunteers were viewed as lazy and uncooperative, UK volunteers as domineering and controlling. Not the best start. Even our female counterparts had expected to dislike us because of previous experiences (happily we weren’t told this until a few weeks in). Essentially, our team dynamic had every reason to fail. Yet despite our distinctions of backgrounds, religious beliefs, races, cultures, languages and a fair few strong characters thrown in, we genuinely made it work, and emerged as a strong, unified team. Yet we also became like the strangest family dynamic! I viewed my team as my siblings before too long, especially my counterpart Tshedi as we formed remarkable bonds that went far deeper than any other relationship. Perhaps the unusual setting we found ourselves in played a part, but even now a year on, they are still some of the first people I reach out to with news or advice.

To conclude, perhaps then, this is what development resembles. Development is often portrayed in quick-fix plan headed by organisations who know little on a grassroots level. Or as a second Mandela movement. But I think development stems from relationships. A small and steady changing of hearts and minds towards social justice. To interact as people, not projects. My ICS experience changed my whole life path towards studying International Development, and it was a unique experience I will always treasure. After all, development must be explored, experienced to grow critically optimistic expectations as a result.