Claude Samaha is Lead Researcher at Basmeh & Zeitooneh and a member of the Protracted Displacement Economies (PDE) team.

Policymakers in Lebanon argue that displaced people, particularly Syrian refugees, are one of the causes of the country’s failing economy. Syrian refugees are often blamed for the lack of electricity, water, jobs and even bread.

At a conference in Brussels in May, Lebanon’s Minister of Social Affairs, Hector Hajjar, declared that hosting Syrian refugees has had negative economic consequences for Lebanon. He accused Syrian refugees of benefiting from “state-subsidized services” and being responsible for “the loss of many job opportunities for the Lebanese… without contributing… taxes.”

A key focus of Hajjar’s comments on services relate to energy subsidies. In reality, however, Lebanon had experienced blackouts for years before Syrian refugees arrived. As Zachary Davis Cuyler argues, ‘the 1975–1990 civil war witnessed the large-scale physical destruction of infrastructure. Postwar reconstruction did not deliver functional refineries or reliable electricity’.

Lebanon’s energy regime became characterised by a set of interconnected vested interests that enabled it to persist despite its inefficiencies. These vested interests include politicians who received kickbacks on high-cost electricity purchases from Turkish mobile power barges, fuel importers who formed a close-knit cartel, and politically connected private generator owners whose wealth and power grew in the gaps created by the state’s shortcomings. Thus even if no refugees moved to Lebanon, blackouts would still occur as a result of decades of utter mismanagement, and the level of energy subsidies would still be an issue of contention.

Hajjar’s comments on employment imply that cash assistance allows Syrians to work for lower wages, pricing out the Lebanese workforce in certain industries. Yet refugees are underemployed, and those who do work are underpaid. Our surveys in displacement-affected communities show that refugees’ employment does not exceed 25%.

The truth is that the economic crisis has amplified poverty among both refugees and ‘host’ communities. Resources and jobs have become increasingly scarce. Due to the economic crisis, hundreds of businesses have closed or reduced personnel over the last two years, and wages have been cut for many of those who do continue to be employed, exacerbating poverty and hardship.

According to the United Nations, nine out of ten Syrian refugees are impoverished. Salah (not his real name), originally from Homs but now living in Tripoli, said: “We have a very bad financial situation… I don’t have a fixed job and I’m currently not working. We don’t have water or electricity… We are unable to buy meat, oil, and milk.”

According to our qualitative interviews, the vast majority of displaced people prefer to be relocated to other (third) countries. Human rights organisations such as Amnesty International are clear that Syria is not a safe place to return to, as returnees may be subjected to intimidation or even direct violence. As Saddam (not his real name), originally from Homs but now living in Bekaa, explained: “Our relatives went back to Syria and were threatened and detained… One of our friends was detained in Homs for several months… He’s not mentally well anymore.”

The current official narrative is that refugees are an economic burden. As a result, attitudes toward refugees have changed locally, and inter-communal relations are getting worse, particularly since the start of the economic crisis. Hate speech and falsehoods being spread by some Lebanese media only aggravate this negative situation.

Syrian refugees are being used to detract attention from the Lebanese government’s failure to deal with the economic crisis. They are also being used as a card in an international aid poker game with potentially US$3.2 billion at stake. In other words, the Lebanese and Syrian governments, as well as the donor community and other great powers, address displacement through the lens of their own limited political objectives.

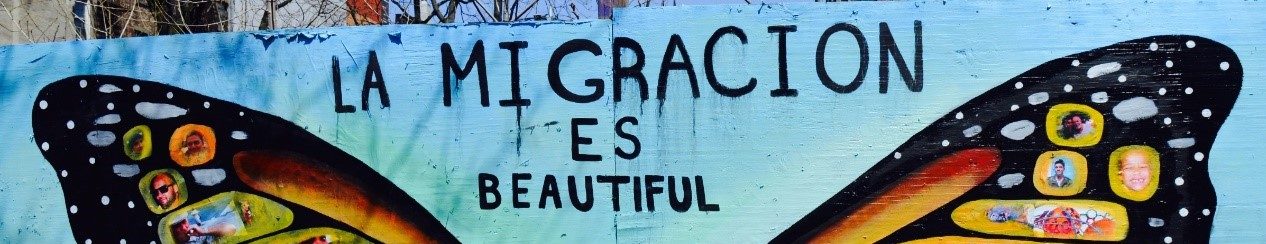

Refugees did not cause Lebanon’s current financial crisis. The country’s elites are responsible for that. As Sahar Atrache highlights, contrary to popular belief, Lebanon has benefited from the presence of refugees. Along with substantial levels of international aid injected into the economy, refugees have contributed to the development of novel approaches to promoting sustainable livelihoods. Syrian and Palestinian refugees have contributed to the establishment of businesses that not only address a range of community needs but also enrich the local culture.

The blog was originally posted on the Protracted Displacement Economies website. PDE is a project funded by UK Research and Innovation through the Global Challenges Research Fund (grant reference number ES/T004509/1).

The UK’s hypocritical and heartless approach to displacement and migration

Sunit Bagree is Communications Manager for Protracted Displacement Economies (PDE), a project funded by UK Research and Innovation through the Global Challenges Research Fund (grant reference number ES/T004509/1). This is a joint PDE-Sussex Centre for Migration Research blog post.

Referring to small boats crossing the Channel, the UK Home Secretary, Suella Braverman, has claimed that she is intent on “stopping the invasion on our southern coast.” This is the type of language traditionally employed by the far-right. It is worth noting that Braverman made this comment just the day after an extremist threw petrol bombs at an immigration centre in Dover.

The Home Secretary ignores several basic facts. First, research suggests that the majority of people crossing the Channel in small boats are likely to be refugees. Second, provided they make their presence known to authorities, asylum seekers who arrive via unofficial routes are protected under international refugee law. Those who are not asylum seekers still have rights under international human rights law. Third, out of 31 European countries, 18 had more asylum applications per capita last year than the UK. And it is not like Europe is particularly generous: 83% of the world’s refugees are hosted in the Global South.

What is particularly ironic is that British foreign policy can drive armed conflict and, as a result, forced displacement. Recent examples include the UK’s arming of the Saudi Arabian-led coalition responsible for devastating attacks in Yemen and its co-financing of liquid natural gas projects that are fuelling violence in Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado region.

This is not the first time that senior British ministers have used xenophobic, dehumanising language. For example, in July 2015, David Cameron, then Prime Minister, spoke of “a swarm of people coming across the Mediterranean.” Less than a fortnight later, the then Foreign Secretary, Philip Hammond, used the term ‘marauding’ in relation to African migrants in Calais hoping to come to the UK.

I was associated with a letter published in the Guardian in response to Hammond’s comments. The letter argued: ‘It is not “marauding” African migrants, but the UK and other wealthy nations that are threatening living standards and causing poverty for people in Africa and across the world’. While acknowledging that most of the migrants arriving in Europe (and many of those trapped in Calais) were people fleeing war and persecution, the letter deliberately refers to those who were simply fleeing poverty. In doing so, it touches on some – and only some – of the economic and climate injustices perpetrated by the UK.

But UK policy on displacement and migration does not have to be hypocritical or heartless. It is entirely possible for domestic and foreign affairs to be conducted in ways that are far more ethical. Moreover, while there are certainly differences between the UK and countries in the Global South affected by protracted displacement, our research indicates that there are also some clear parallels. For example, all countries need to move beyond a simplistic approach to economics.

Take unpaid care work. Our surveys demonstrate that, on average, people in countries affected by protracted displacement spend seven hours a day on caring for those they live with. In the UK, there are around 13 million people caring for an ill, older or disabled family member or friend. Yet, around the globe, unpaid care work does not achieve the recognition it deserves in economic accounting and policymaking. Carers, who are disproportionately women, often struggle as a result.

Or take mutual aid. On average, 30% of people in countries affected by protracted displacement give or receive financial support and 40% give or receive non-financial support. Indeed, over half of all respondents in our research locations in Africa and Asia have more than one neighbour from whom they can ask for help. In the UK, there are an estimated 4,300 mutual aid groups, with 3 million volunteers helping people in their local community. Yet economic policymakers around the world largely fail to understand mutual aid and create a supportive environment for mutual aid groups.

No one is to ‘blame’ for being a refugee – those who have not had to flee from persecution should understand that they are simply fortunate. Creating sufficient safe, legal routes for asylum seekers to come to the UK (and other Global North countries) would decimate the business model of the organised criminal gangs that traffic vulnerable people.

And all (or virtually all) of us are migrants or the descendants of migrants. Instead of throwing around ridiculous insults, Braverman and the rest of the UK government should reflect on our common humanity, and work to realise the potential of all people in line with the UK’s international obligations and pledges.