What is the direction of travel suggested by the five of the latest agreements?

The UK’s accession negotiation to the Asia-Pacific Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) trade deal was formally launched in June.[1] While joining the CPTPP is driven by the UK’s geopolitical strategy, pivoted to the Indo-Pacific,[2] its direct economic benefits look rather slim considering the UK’s current trade and investment relationship with CPTPP countries and the bilateral Free Trade Agreement (Japan) / continuity agreements (Canada, Chile, Mexico, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam) already achieved.[3] Much of the discussion about the CPTPP has been mainly in the context of political motives and economic benefits.[4] There has been less discussion regarding the regulatory challenges the UK would face in joining the CPTPP and the possible implications for UK society.[5] By shedding light on digital trade, this Briefing Paper aims to examine the implications that joining the CPTPP would have for the UK’s regulatory strategy and what kind of impact it could have for future trade negotiations.[6] To examine these issues, we take into account major policy developments that the UK has made, including the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA), the UK-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) and the UK-Australia FTA Agreement in Principle (AIP).

This Briefing Paper is part of a pair of papers that examine the implications for domestic regulatory strategy and to the UK’s future FTA negotiations, of the UK joining the CPTPP. The companion Briefing Paper – Briefing Paper 60 – focuses on the issue of food standards and regulations.

Although there is no settled definition of digital trade, international organisations (OECD, WTO and IMF) define it as ‘all trade that is digitally ordered and/or digitally delivered’[7], whereby digitally ordered trade is essentially international e-commerce and digitally delivered trade encompasses certain services. One of the major challenges for international trade rules is how to address cross-border data flows, data storage and digital information to promote digital trade while ensuring public policy, such as data privacy, security and cybersecurity across borders. Since the approach taken for digital governance differs across countries – reflecting the level of development, economic interests, societal norms and culture – creating a consensus on how to regulate digital trade at the multinational level is extremely difficult.[8]

Broadly speaking, there are three major approaches to digital policy: the US approach, the Chinese approach, and the EU approach.[9] The US takes a more market-driven, open rules approach in which data are regarded as a commercial asset; China’s model is state-led digital governance with strong digital trade restrictions such as the data localisation requirement[10]; and the EU puts greater priority on public policy objectives, such as a high level of consumer and private data protection and competition policy, in developing its digital policy.[11] The major players in the global digital economy are the US and China. For example, 90 per cent of the market capitalisation value of the world’s 70 largest digital platforms are dominated by these two countries while Europe’s share accounts for only 4 per cent.[12] This underlines the importance of understanding their different regulatory approaches, in combination with their market influence. In contrast to the US’s market-driven approach, the EU normally separates out issues of data privacy from its trade deals since data privacy is a citizen’s fundamental right in the EU Charter.[13] The EU sets its adequacy decision on data protection, the decision which the EU makes on whether a country outside the EU offers an adequate level of data protection (as the EU does) as a pre-condition of free data flow when it negotiates a digital trade chapter in an FTA.[14] Although the EU is not the top player in the global digital economy, the EU’s policy on General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is influencing other countries’ legislators to review their data privacy rules via what is called the “Brussels effect”. Considering the EU’s market size, an adequacy decision on data protection from the EU Commission as a condition of free data flow is not negligible.[15]

At the international level, while negotiations on trade-related aspects of electronic commerce started in 2019 at the WTO, Asia-Pacific countries such as Singapore, Australia, New Zealand and Japan, have been actively creating FTAs with digital trade chapters or digital economy agreements over the last several years. These agreements are focusing on market-driven digital trade and innovation (along the lines of the US approach). Notably, the recent Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) between Chile, New Zealand and Singapore and the Australia-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement (DEA)[16] – which encompass digital economy in the wider context rather than digital trade – demonstrate that Asia-Pacific middle-sized powers are trying to be rule-makers in global digital trade governance.[17] For example, the Australian Government explains that the DEA “sets new global benchmarks for trade rules”.[18]

Since the UK is now developing its own digital trade strategy, understanding the EU’s approach to digital trade governance, in contrast to the US’s approach and Asia-Pacific countries’ approach is important. We do not examine China’s digital trade approach in its FTAs in this paper, partly due to space constraints, and partly as the UK is not likely to conclude a digital trade deal with China in the near future.

Digital trade is very significant for the UK. According to ONS data, more than half of services trade are delivered digitally, accounting for 67% (£190bn) of UK services exports and 52% (£91bn) of UK services imports in 2018.[19] In the policy realm, the UK Government set out five missions in the UK National Data Strategy, including ‘championing the international flow of data’.[20] However, the Strategy ended up just listing aspirations. Practical solutions to achieve the aspirations or to resolve emergent trade-offs are lacking. For instance, the Strategy aims to build trust in the use of data and facilitate cross-border data flows. But how to simultaneously achieve both aspirations is not addressed.

The UK Government is trying to use Free Trade Agreements as a major policy tool to become a ‘champion of the international flow of data’ while applying EU-style digital governance at home and expressing the possibility of future divergence.[21] Indeed, departing from the EU’s approach, the UK’s foreign policy re-orientation towards the Indo-Pacific would appear to be pushing the UK towards Asia-Pacific-style digital trade rules, which is more closely aligned with the US’s market-driven approach. The UK-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) is a clear departure from EU-style digital trade governance that enshrines data protection as a fundamental right of the citizen. For example, CEPA strictly prohibits measures prohibiting free data flow with limited safeguards for governments to take actions for public policy purposes.[22] The UK Government seems to envisage CEPA as a stepping stone towards CPTPP and beyond, such as the UK-Australia FTA (agreed in principle in June 2021), the future UK-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement, the negotiation of which was launched in June 2021,[23]a future UK-New Zealand FTA and a UK-US trade deal (which is not likely to happen in the near future though).[24]

Although the scope and depth of digital trade chapters in FTAs, as well as digital economy agreements differ – reflecting the FTA parties’ interests, level of development and political system – the UK’s policy tendency to shift away from EU digital governance raises three questions:

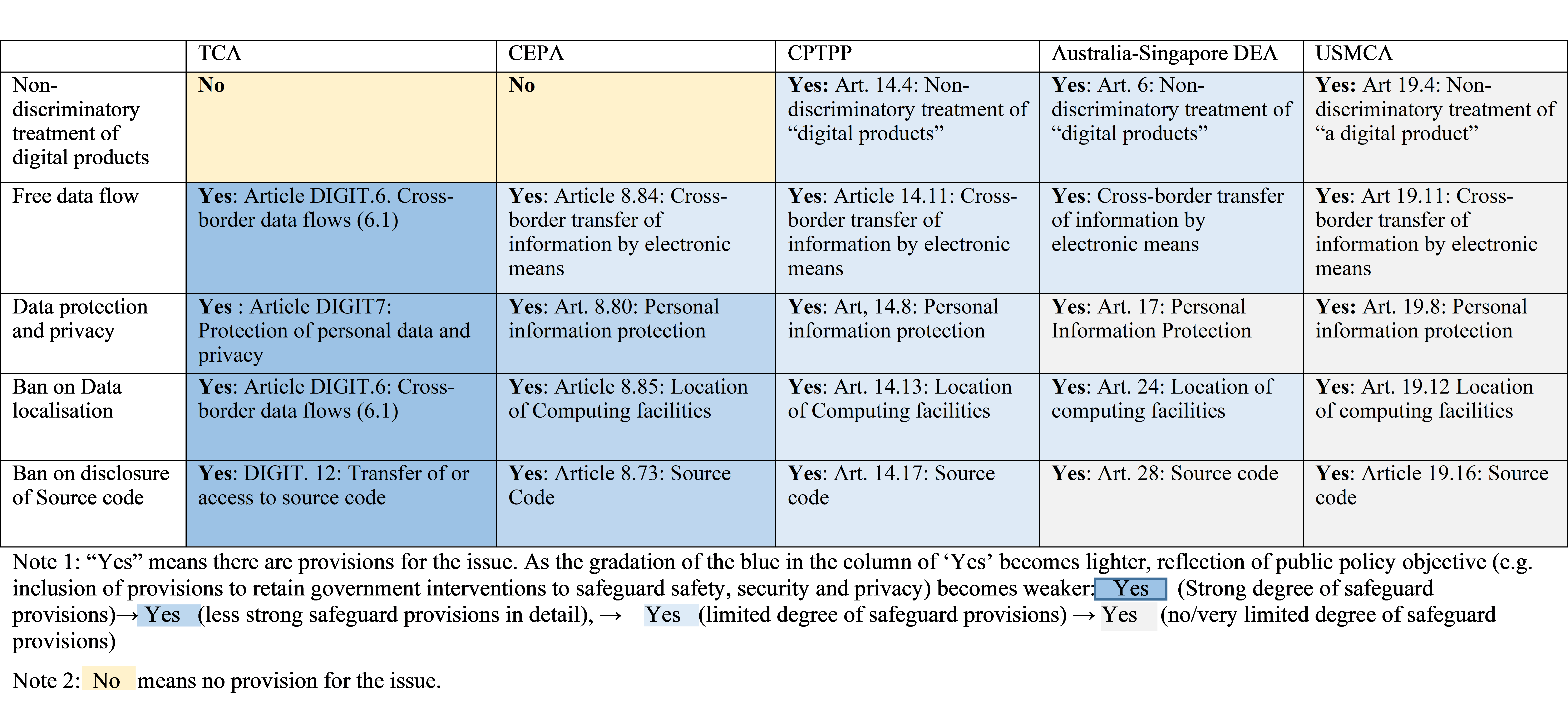

In order to understand the UK’s potential policy shift on these issues in FTAs, we focus on three distinct aspects that are at the core of the differences between competing regulatory approaches to digital trade: (i) the scope and degree of general prohibitions of government intervention for public policy objectives in the areas of free data flows, data localisation and source code provisions, respectively; (ii) data protection and privacy provisions; and (iii) the non-discrimination principle for digital products. We do so by comparing five of the most recent digital trade agreements that are at the forefront of digital trade policy-making: the TCA, CEPA, CPTPP, Australia-Singapore DEA and US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). We include the USMCA as it allows the juxtaposition of the US’s approach in contrast to the TCA, which naturally reflects the EU’s digital trade approach. Table 1 compares how these five agreements deal with the aforementioned aspects by giving an indication of the strength of the policy stance taken: the lighter the blue shading, the lower the degree of government safeguarding and the more the approach to data privacy leans towards a self-regulatory regime.

(See Annex for the table which describes more in detail)

Table 1 reveals two strong points. First, we can clearly see that the degree of consideration for public policy space in the related provisions (free data flow, ban on data localisation, and ban on disclosure of source code) under the TCA is highest and the degree of consideration in these provisions under USMCA is the lowest, amongst the five FTAs.

The approach taken by the TCA and the other four FTAs in terms of public policy is very different. In the case of the TCA, the general provisions: ‘right to regulate’ (TCA DIGIT 3) and ‘exceptions’ (TCA DIGIT 4), which give much stronger rights to governments to safeguard public policy objectives than those under the WTO, apply to all provisions in the digital trade chapter. Additional detailed safeguarding clauses are then also provided case by case. Regarding the provisions on free data flow, ban on data localisation and ban on disclosure of source code, the four agreements (CEPA, CPTPP, Australia-Singapore DEA and USMCA) take the WTO approach of general exceptions to safeguard public policy objectives. Given that free trade is the WTO’s primacy, governments are requested to justify that measures are not arbitrarily discriminatory or a disguised form of protectionism.[25] WTO jurisprudence indicates that justifying public policy measures under the WTO general exceptions is not easy.[26]

The provisions in CEPA are basically copied from the CPTPP and expand the scope by incorporating some clauses from the Japan-US digital trade agreement (2019) to make the agreement more innovation-friendly. Yet, the degree of safeguarding public policy objectives under CEPA is slightly higher than in the CPTPP. Although the Australia-Singapore DEA is based on the CPTPP approach, it goes a step further than the CPTPP (to the benefit of business stakeholders) with the ban on disclosure of source code given a wider scope (software and related algorithms) and no specific exceptions clause (Australia-Singapore DEA Art.28). The USMCA is an FTA that tries to minimise government intervention for public policy objectives.

The second finding is that the level of the government’s commitment to personal data and privacy protection under the TCA is the highest. The way in which personal data protection is treated has to be examined in conjunction with the free data flow provisions. The EU’s adequacy decisions to the UK are set as a condition of free data flow. Although CEPA copied the provisions of data protection from the CPTPP, the UK and Japan accorded adequacy decisions to each other outside of CEPA. While the CPTPP incorporates a strong priority for free data flows, its provisions regarding each Party’s legal framework for private data protection only recommends taking into account the principles and guidelines of relevant international bodies without any specific reference. The Australia-Singapore DEA and USMCA specifically refer to the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules system and the OECD recommendation of the Council concerning Guidelines governing the Protection of Privacy and Transborder Flows of Personal Data. Also, the APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules (CBPR) system is listed as a valid system to promote compatibility.[27] It should be noted that digital law experts recognised GDPR as a gold standard of private data protection and that the threshold of private data protection under the self-regulatory regime, such as APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules, is lower than GDPR.[28]

The CPTPP is a plurilateral FTA that currently comprises 11 Asia-Pacific economies with different levels of economic development and different political systems.[29] In terms of substance of rules, the CPTPP (originally TPP) is an Asia-Pacific style trade agreement based on the value of liberal markets. The Agreement was shaped by the US’s strong initiatives during the negotiations (2008-2015), including the e-commerce chapter.[30]

The negotiation for accessing a pre-existing agreement such as the CPTPP is completely different from the negotiations that would create a new FTA, where future signatories sit together and draft rules until all parties are in agreement. For CPTPP accession, the UK does not have a right to renegotiate rules and simply has to accept existing CPTPP rules. The CPTPP accession rule requires full compliance with the CPTPP rules as a condition of becoming a member.[31]

According to the CPTPP accession procedure, once the commencement of the accession process is decided and the accession working group is established, at the first meeting, the UK has to demonstrate that UK domestic laws and regulations can comply with the obligations of the CPTPP. If that is not the case, the UK has to identify any additional changes to be made to its domestic laws and regulations.

If the UK cannot change CPTPP rules, is there any way of derogation? In practice, existing CPTPP members have bilaterally exchanged letters, what are called “side instruments (or side letters)” in order to arrange a special bilateral arrangement for derogation purposes. For example, Canada arranged forty side instruments (four side instruments with Australia, four with Japan, five with Malaysia, eight with Vietnam and so on). The type of side instruments differs among countries from agreements on agricultural products, culture, e-commerce, motor vehicles, Geographical Indications, and Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS).

It seems that the UK would not be easily allowed to use side instruments to derogate from some of its obligations – though it may be possible.[32] This is because the UK is the first country that would be acceding to the CPTPP. In order to differentiate CPTPP from the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the rules of which are shallower and narrower than CPTPP,[33] CPTPP members presumably do not wish to create a precedence of easy derogations from the existing set of rules for the first acceding country. In addition, the UK is a highly developed open economy and will become the second-largest economy after Japan among CPTPP members. Thus, expectations are high for full compliance with existing obligations.

In joining the CPTPP, the UK would face some policy challenges. The first challenge is to accept CPTPP rules that provide narrower safeguarding exceptions than those under TCA or CEPA. It should be noted that the digital trade provisions in the CPTPP are subject to dispute settlement (Chapter 28).

The CPTPP has two layers of requirement as the condition for adopting or maintaining measures to achieve a public policy objective, whereas CEPA sets only one layer of requirement. The first condition is that a public policy measure does not constitute a means of arbitrary/unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on trade. The second condition is that an imposed restriction is not greater than required to achieve the objective (CPTPP Art. 14.13.3. (a) and (b)). CEPA requires only the first condition to be met to justify public policy measures if a CPTPP partner challenges its legitimacy under the CPTPP dispute settlement mechanism.[34]

The scope of CEPA is wider – including software and related algorithms – than that of CPTPP which covers only software. However, CEPA provides safeguarding exceptions in more detail than under CPTPP. The UK has to carefully examine how to achieve a sensitive balance between economic objectives and public policy objectives under its FTAs.

The second challenge is how to maintain the UK’s high standards of data protection while ensuring free data flow with CPTPP members under the CPTPP rules. Although the requirement on free data flows of CEPA is slightly stronger than that of CPTPP, the UK and Japan have separately concluded adequacy decisions, as explained earlier. In comparison, CPTPP’s data protection, both in terms of text and in practice, is very different from the TCA and CEPA. In terms of the legal text, its personal data and privacy provisions just recommend taking into account ‘principles and guidelines of relevant international bodies’ when a member adopts or maintains the data privacy legal framework (CPTPP Art.14.8.2). To promote compatibility among CPTPP members, autonomous recognition (e.g. adequacy decision) and mutual arrangement or broader international frameworks are listed as possible mechanisms to promote compatibility. However, in practice, the data protection mechanisms applied among CPTPP members are not clear.

Whilst the UK’s legal framework on data privacy (UK GDPR and the Data Protection Act 2018) is of a high standard, in line with the EU’s GDPR,[35] CPTPP members have different types and levels of data privacy law at the domestic level. If the UK accepted the free data flow provisions under the CPTPP, the UK would have to accept free flows of data with countries that do not have a GDPR adequacy decision from the EU. To date, only three countries (Canada, Japan and New Zealand) out of 11 CPTPP members have received an adequacy decision from the EU. This could be indicative that the level of data privacy protection by eight members (Australia, Brunei, Chile, Malaysia, Mexico, Peru, Singapore and Viet Nam) is lower than the level of the EU’s GDPR. Japan received the EU’s adequacy decision on data privacy in conjunction with the EU-Japan EPA. To obtain the EU’s adequacy decision, Japan introduced a supplementary law that provides a two-tier data protection regime with a different level of protection for data from the EU. In this way, the threshold of GDPR is maintained in Japan.

Although the EU has provided two adequacy decisions (GDPR and the Law Enforcement Directive) to the UK (June 2020), the EU’s adequacy decisions for the UK have a four-year sunset clause and are not permanent. The use of a sunset clause is noteworthy, as it is much stricter than a normal EU four-year review. The EU took the position that it will take into account regulatory divergence including changes in domestic law or legal/practical implication of divergence at the time of review. In addition, any future rules for the onward transfer of personal data to third countries are taken into account for renewal (GDPR Art. 45. 2(a)). If the UK accedes to the CPTPP, not only the legal text, but possible mechanisms in practice (e.g. labelling data) to prevent onward data transfers to third countries with lower data privacy thresholds, would greatly impact on the EU’s adequacy decisions for the UK in this regard.

The third challenge is whether the UK can accept the fundamental non-discriminatory treatment of digital products (CPTPP Art. 14.4).[36] Since the UK has not included this non-discrimination principle in the TCA and CEPA, thereby following the EU’s stance in its FTAs, the CPTPP is likely to become the first FTA for the UK to accept the non-discrimination principle for digital products. Thus, the implication of a change in the fundamental principle should be carefully analysed, together with the scope of the principle. First of all, the UK carved out audio-visual services from the digital trade provisions in the TCA. In addition to audio-visual services, CEPA carved out wider sectors including gambling and betting services, broadcasting services, services of notaries or equivalent professions and legal representation services (CEPA Art. 8.70.5) from the digital trade chapter. Although the non-discriminatory clause under CPTPP does not apply to some areas, such as intellectual property or subsidies or grants provided by government and broadcasting, the UK has to examine how this relates to the carved-out sectors in its existing FTAs.

Second, the UK ought to be aware of the implications for future digital trade negotiations with the US once it has accepted the non-discrimination principle. In the USMCA, the US strategically switched a non-discriminatory treatment of ‘digital products’ – such as in the CPTPP and the Australia-Singapore DEA – to “a digital product”. While the entire group of foreign and domestic products is compared in the case of “digital products”, individual foreign and domestic products are compared in the case of “a digital product”.[37] This means that if the UK targeted a specific American company in the pursuit of its digital policy, it could be deemed as discriminatory and could be challenged by the US using dispute settlement in a trade deal.

A solid and clear digital trade and data strategy for the UK is needed. Every country is facing challenges in formulating digital trade policy, as digital governance is technically complex and influences not only businesses but also non-business stakeholders including consumers, workers, and citizens. In addition, digital governance encompasses a wide range of policy areas including consumer protection policy, industrial policy, competition policy, intellectual property rights, cybersecurity, and human rights. Trade policy cannot be detached from other public policy. The UK Government has to be aware that signing up to a new FTA, is likely to constrain domestic policy and impact domestic outcomes. Without careful consideration by the Government, this could be in unforeseen ways, which may conflict with public policy objectives.

Thus far, the UK has signed two FTAs (TCA and CEPA) that have a substantive digital trade chapter. The UK-Australia FTA is likely to be the third one, prior to potentially joining the CPTPP. Taking into account the degree of ambition expressed in the UK-Australia agreement in principle, [38] the Australia-Singapore DEA may be serving as a template for the digital trade chapter in the UK-Australia FTA as doing so could facilitate on-going negotiations for the Singapore-UK Digital Economy Agreement. While UK business expects these FTAs to create business opportunities and promote digital trade between the UK and the Asia-Pacific countries, non-business stakeholders are expressing concerns about policy developments made under CEPA and implications for the UK’s future FTA negotiations.[39]

Rather than concluding digital chapters in its FTAs one by one, the UK first has to establish a cross-cutting digital trade strategy, which would publicly set out the UK’s regulatory objectives and clearly explain a way to achieve them. The strategy has to be crafted through cross-departmental coordination to reflect a wide range of policy areas. And multi-stakeholder consultations are needed, to take into account non-business stakeholders’ concerns, since building trust is key for further digital innovation.[40] As explained earlier, the UK does not have the right to change CPTPP digital trade provisions and may have little scope for derogations via side letters. Therefore, the potential implications of CPTPP provisions to the whole of UK society should be carefully examined. How can the UK build trust in a digital society, while finding a way to achieve open digital trade with a range of different countries using FTAs or digital trade agreements, is a big question the UK Government urgently needs to address.

[1] UK and CPTPP nations launch formal negotiations – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[2] Global Britain in a Competitive Age: the Integrated Review of Security, Defence, Development and Foreign Policy – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[3] The value of the CPTPP for the UK: https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2021/02/03/the-value-of-the-cptpp-for-the-uk/

[4] For example, see UK Accession to CPTPP: The UK’s Strategic Approach (publishing.service.gov.uk); and Why joining the CPTPP is a smart move for the UK | Chatham House – International Affairs Think Tank

[5] Challenges ahead for the UK to join CPTPP: https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2021/04/16/challenges-ahead-for-the-uk-to-join-cptpp/

[6] UKTPO BP No. 60 spotlights SPS chapter in the CPTPP and UK food standards.

[7] Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade Version 1 (OECD, WTO, and IMF). Handbook on Measuring Digital Trade (oecd.org)

[8] Aaronson, S.A. (2019). Data is different, and that’s why the world needs a new approach to governing cross-border data flows, Digital Policy, Regulation and Governance, Vol. 21 No. 5, pp. 441-460. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPRG-03-

[9] Jones, E. et al (2021). The UK and digital trade: Which way forward? BSG-WP-2021/038, February 2021. BSG-WP-2021-038_0.pdf (ox.ac.uk)

[10] Gao, X. (2020). State-led digital governance in Contemporary China, In Naito, H. and Macilenaite, V. (Ed.), State Capacity Building in Contemporary China (pp.29-26). Springer.

[11] For example, the Digital Market Act aims to regulate some large online platforms and act as a “gatekeeper” (e.g. the Big Five tech giants) in digital markets so that they behave in a fair way online. The Digital Services Act sets rules for online intermediary services by providing obligations in accordance with their role, size and impact in the online ecosystem. The Digital Services Act package | Shaping Europe’s digital future (europa.eu)).

[12] Digital Economy Report (2019). UNCTAD. Digital Economy Report (unctad.org)

[13] Articles 7 and 8, Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU: Article 6 (1) of the European Union.

[14] The EU-Japan EPA does not include a free data flow provision. The TCA is EU’s first FTA that includes the free data flow provision (DIGIT 6.1) with primacy of data protection (DIGIT 7). As for the EU’s adequacy decision: Adequacy decisions | European Commission (europa.eu)

[15] Europe’s new data protection rules export privacy standards worldwide – POLITICO. And Rustad, M. L. and Koenig T, H. (2018). Towards a Global Data Privacy Standard, Vol.71 Florida Law Review.365. https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol71/iss2/3.

[16] Both agreements were concluded in 2020.

[17] Honey, S. (2021). Asia-Pacific digital trade policy innovation, In Borchert, I and Winters, L. A. (Ed.). Addressing impediments to digital trade (pp. 217-239). CEPR press. Addressing Impediments to Digital Trade.2021CEPR.UKTPO.pdf

[18] Australia-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement | Australian Government Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (dfat.gov.au)

[19] “Understanding and measuring cross-border digital trade Final Research Report”, DIT and DSMS, 14 May 2020. Understanding and measuring cross-border digital trade (publishing.service.gov.uk)

[20] The other four missions are: unlocking the value of data across the economy, transforming government’s use of data, maintaining pro-growth and trusted data regime, and ensuring the security and resilience of data infrastructure. See: National Data Strategy – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[21] House of Commons International Trade Committee, Oral evidence: Digital Trade and data, HC 1096. https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/1863/pdf/

[22] See the digital chapter in CEPA in comparison with the EU-Japan FTA, The UK-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement: Lessons for the UK’s future trade agreements « UK Trade Policy Observatory (sussex.ac.uk)

[23] UK and Singapore kickstart negotiations on cutting-edge digital trade agreement – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[24] U.K. Trade Secretary Downplays Outlook for U.S. Trade Deal Soon – Bloomberg

[25] The Australia and Singapore DEA simply incorporates WTO general exception clauses (GATT XX and General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) XIV) that apply to all chapters with some exceptions (DEA Art. 3).

[26] GATT-AI-2012-Art20 (wto.org) ; gats_art14_jur.pdf (wto.org) and Yakovleva, S. and Irion, K. (2020). Pitching trade against privacy: reconciling EU governance of personal data flows with external trade, International Data Privacy Law, Vol.10, No. 3, pp.201-222.

[27] CBPR System is “a government-backed data privacy certification that companies can join to demonstrate compliance with internationally-recognized data privacy protections”. What is the Cross-Border Privacy Rules System? (apec.org)

[28] House of Commons International Trade Committee, Oral evidence: Digital trade and data, HC 1096. https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/1611/pdf/

[29] Among 11 CPTPP members, four countries (Brunei, Chile, Malaysia, and Peru) have not yet ratified the Agreement.

[30] Azmeh, S. and Foster, C. (2016). The TPP and the digital trade agenda: Digital industrial policy and Silicon Valley’s influence on new trade agreements, Working Paper Series, No. 16-175, LSE, Department of International Development, London. https://www.lse.ac.uk/international-development/Assets/Documents/PDFs/Working-Papers/WP175.pdf

[31]Decision by the Commission of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership regarding Accession Process of the CPTPP, CPTPP/COM/2019/D002, 19 January 2019.

[32] When the UK formally submitted the accession request on 1st February 2021, the Japanese Minister of Foreign Affairs strongly emphasised “the importance for the United Kingdom to show to other members as well as to the public, repeatedly, its determination to meet the high standards of the CPTPP, including to comply with all of the existing rules in the CPTPP without exception”.

[33] RCEP: What’s in it for Asia and the Pacific? – Yasuyuki Sawada | Asian Development Bank (adb.org)

[34] Digital trade provisions are within the scope of dispute settlement in other four FTAs (TCA, CEPA, Australia-Singapore DEA, and USMCA) as well.

[35] Buttarelli, G. (2016), The EU GDPR as a clarion call for a new global digital gold standard, International Data Privacy Law, Volume 6, Issue 2, pp. 77–78.

[36] CPTPP defines ‘Digital products’ as a computer programme, text, video, image, sound recording or other product that is digitally encoded, produced for commercial sale or distribution, and that can be transmitted electronically.

[37] See analysis of possible legal interpretation in Digital Trade Agreements and Domestic Policy (cato.org)

[38] See 3.2 Digital trade in the UK-Australia FTA negotiations: agreement in principle. UK-Australia FTA negotiations: agreement in principle – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[39] House of Commons International Trade Committee (2021). Digital Trade and Data, First Report of Session 2021-2022. Digital trade and data (parliament.uk)

[40] Kende, M. (2021). The flip side of free –Understanding the economics of the internet, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. And Snower, D J and Twoney, P. (2020). Humanistic digital governance, CESifo Working Paper No. 8792.