3 July 2024

Tom Arnold is a Researcher at the Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place at the University of Liverpool; Patrick Holden is a Reader in International Relations at the University of Plymouth; Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School; and Ioannis Papadakis is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Inclusive Trade based at the University of Sussex.

Freeports have been a central part of the UK Government’s regional development policy over the last five years. The 2019 Conservative Party manifesto pledged to create “up to ten Freeports around the UK”,[1] emphasising their potential to create new jobs and additional income streams for local government. They were also promoted as key to improving the UK’s international trade prospects following its exit from the European Union. UK government has specified three economic objectives for Freeports: to establish them as hubs for global trade and investment; to promote regeneration and job creation; and to create hotbeds for innovation.[2]

Despite this, Freeports have not featured strongly in the current general election campaign. The 2024 Conservative manifesto includes a promise to “create more Freeports and Business Rates Retention zones”, emphasising their potential to create new jobs and provide additional income streams to local government.[3] While the opposition Labour Party pledges to develop Local Growth Plans aligned to national industrial strategy, there is no mention of Freeports.

The UK Freeport programme looks likely to continue in some form, regardless of the outcome of the election. The 2023 Autumn Statement extended tax relief funding for English Freeports from 2026 to 2031, meaning Freeport operators and occupiers will benefit from reliefs on stamp duty, business rates and employer national insurance until this ‘sunset date’. Nevertheless, several concerns will need to be addressed by the next government. This piece sets out the key issues for Freeports over the coming months and years, and suggestions for improving on the current model.

In April 2024, the House of Commons Business and Trade Committee published the findings of its inquiry into the performance of Freeports and investment zones in England, to which some authors of this article contributed evidence.[4] The report summarises the benefits and limitations of the UK Freeport model, highlighting evidence which suggests:

Despite these concerns, we argue that the UK Freeport experiment should not be abandoned, but may need modification. Given the limitations of the customs benefits associated with Freeports, the government should focus on the role they can play as part of an active, place-based industrial strategy. While Freeports have been portrayed as a central element of the government’s ‘Levelling Up’ regional development policy, the relationship with broader government objectives on key national issues such as net zero is unclear.

This confusion is partly a result of the dual purpose of the current UK Freeport model, which aims to both boost international trade and operate as traditional Special Economic Zones with a focus on attracting jobs and regenerating ‘left behind’ places. Aligning Freeports more closely with national policy targets and providing greater certainty about the purpose of regional policy could help to clarify their purpose. This could be particularly significant in places which continue to face acute socio-economic problems following the mass decline of industry in the second half of the 20th century.

To achieve this, we highlight five areas for improvement in the current government’s strategy for Freeports.

Align with other special economic zones. In addition to Freeports, there are two other main special economic zone (SEZ) programmes currently operational in the UK: Investment Zones (introduced in 2023, with 13 across the UK); and Enterprise Zones (introduced in 2011 and expanded in 2016, with 48 across England only). The presence of three different types of SEZ presents complexities for local government in attracting investment and developing industrial strategy, particularly in areas where all three are present (such as Liverpool City Region). As part of a broader industrial strategy, the government should be clear about the purpose of each SEZ and where possible align governance of SEZs under a single accountable body (such as a Mayoral Combined Authority. Where appropriate SEZs could be merged to create clusters with complementary activities – comprising universities, ports and dynamic SMEs. There is particular potential to align Freeport activity with national and local objectives to achieve net zero carbon emissions, particularly through decarbonisation of freight transport.

Assess the value of customs benefits. The government should review whether customs reliefs are worth retaining or should be wound down to save money and time for local authorities and to allow more focus on the place-based industrial policy elements of the programme. Policies and funding could be focused more narrowly on other Freeport priorities such as improving infrastructure and upskilling local workers. The UK Freeport model should be understood more accurately as a type of SEZ rather than a focus on international trade.

Enhance governance. The Business and Trade Committee report recommends that accountability for Freeports should be held by a single leader, in the form of an elected ‘metro mayor’. This can offer clarity for businesses, the public and other stakeholders. However, only three English Freeports are currently located in areas with a mayoral combined authority (East Midlands, Liverpool City Region and Teesside). For Freeports without an elected mayor, it is less clear who the single accountable figure should be, but local authority leaders may be most appropriate for this role. While Freeports should be enabled to exercise flexibility in shaping policies to align with local aims and objectives, the UK government should retain overall scrutiny of the Freeport programme in England.

Improve transparency. While fears about the disconnection of UK Freeports from democratic accountability are exaggerated, public concern is understandable given the shortage of publicly available information about their geographies and powers. Efforts should be made to ensure all Freeport bodies publish clear, accessible and easy to digest information about site locations, governance arrangements and mechanisms for allocating retained business rates.[10] Making this information publicly available will facilitate learning about the effectiveness of UK Freeports.

Improve evaluation. The government should work with Freeports to develop metrics tracking benefits to businesses, the effectiveness of Freeport policies, and the costs and benefits of tax reliefs. The current Freeport programme has a strong monitoring and evaluation system in place at the national level, but there are challenges in the provision of local data and developing sound counterfactuals.

While Freeports have not featured strongly in the 2024 general election campaign, the issues the current UK Government purports that they resolve – particularly improving economic prospects in ‘left behind’ places – will remain central to the success of the next government. We suggest not throwing the baby out with the bathwater but reassessing the UK Freeport model as part of a broader place-based industrial strategy, including due scepticism regarding the trade effects.

[1] Conservative Party manifesto (2019) https://assets-global.website-files.com/5da42e2cae7ebd3f8bde353c/5dda924905da587992a064ba_Conservative%202019%20Manifesto.pdf (p.57)

[2] HM Treasury (2020) Freeports: bidding prospectus. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/935493/Freeports_Bidding_Prospectus_web_final.pdf

[3] Conservative Party manifesto (2024) https://public.conservatives.com/static/documents/GE2024/Conservative-Manifesto-GE2024.pdf

[4] House of Commons Business and Trade Committee (2024) Performance of investment zones and freeport in England. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/44455/documents/221158/default/

[5] Peter Holmes and Guillermo Larbalestier (2021) Two key things to know about Freeports. https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2021/02/25/two-key-things-to-know-about-Freeports/

[6] Peter Holmes, Anna Jerzewska and Gullermo Larbalestier (2022) ‘Exporting from UK Freeports: Duty Drawback, Origin and Subsidies.’ UKTPO Briefing Paper 69. https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/files/2022/09/BP-69-Freeports-FINAL-28.09.22.pdf

[7] House of Commons Business and Trade Committee (2024)

[8] Business and Trade Committee (2023) Oral evidence: the performance of investment zones and Freeports in England. https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/13744/html/ (Q9)

[9] Tees Valley Review (2024) https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65ba58ec3be8ad0010a081a9/Tees_Valley_Review_Report.pdf

[10] Nichola Harmer, Patrick Holden and Guillermo Larbalestier (2023) Written evidence submitted to the Business and Trade Committee inquiry into the performance of investment zones and freeports in England. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/124415/html/

Additional Information

The authors would like to thank Guillermo Larbalastier for earlier research input and advice. Guillermo is not responsible for any views expressed in this article. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Charlotte Humma July 3rd, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

June 28, 2024

June 28, 2024

Anupama Sen is a Research Assistant in International Trade (Economics) at the UKTPO.

For nearly a decade, China has been the linchpin of global supply chains, thanks to its competitive labour costs and vast manufacturing prowess, earning it a moniker as the ‘factory of the world’. China’s strong manufacturing position extends to the automotive industry. Against that backdrop, starting on 4 July 2024, the EU will implement tariffs, in the form of countervailing duties (CVDs) ranging from 17% to 38%, on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs). These duties on Chinese EV imports will be on top of an existing 10% duty, thereby reaching a peak of 48%. The decision to levy further duties follows an investigation by the European Commission launched in October to investigate Chinese subsidies distorting EV prices and posing unfair competition risks to European carmakers. Thus, the tariffs are applied on a company-specific basis, tailored to the level of subsidies allegedly received by Chinese firms.

The EU’s tariffs on Chinese EVs could be seen as a strategic move aimed at reducing its dependency on China in this sector whilst at the same time stimulating domestic EV production. While some may view this policy as protectionist or neo-mercantilist, it could alternatively be seen as a prudent industrial strategy to foster economic resilience for the EU and to create a level playing field in the global market for EVs. This blog explores the necessity for such a strategy, supported by data illustrating the EU’s growing reliance on Chinese EV imports.

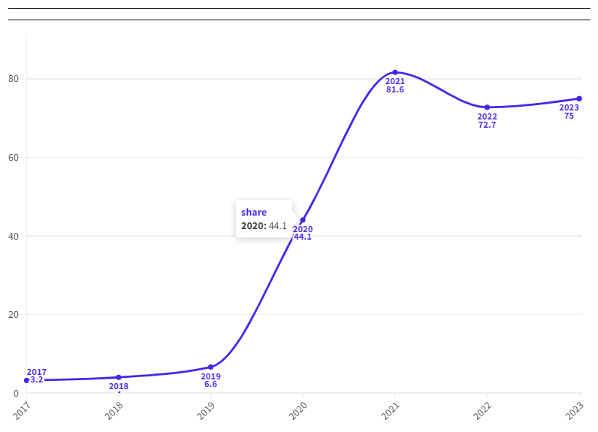

Imports of Chinese produced EVs into the EU market have increased significantly over recent years. Table 1 presents the import values for the car industry and electric vehicles (EVs) from 2017 to 2023, while Figure 1 shows the share of EVs within the total car industry imports. The share of EV’s in total car imports from China rose substantially from 3.2% in 2017 to 81.6% in 2021, with a slight rebound thereafter. While it is difficult to pin down any single specific factor that led to this surge in EV imports in 2021, by then China’s EV industry had grown substantially. This was in part due to substantial state subsidies that enabled manufacturers to offer EVs at competitive prices. Additionally, the EU’s commitment to green energy, including incentives from the 2019 Green Deal, had made the market more receptive to EV imports. Lower trade barriers for Chinese EVs in the EU compared to regions like the U.S. also facilitated this surge. However, EU imports from China have been rising in absolute terms throughout the entire period, in both EVs and non-EVs.

|

Year |

Car Industry (billion USD) HS 8703 |

Electric Vehicles (billion USD, HS 870380) |

|

2017 |

0.46 |

0.01 |

|

2018 |

0.61 |

0.02 |

|

2019 |

1.02 |

0.07 |

|

2020 |

2.06 |

0.91 |

|

2021 |

7.03 |

5.74 |

|

2022 |

9.94 |

7.23 |

|

2023 |

13.96 |

10.47 |

Source: UN Comtrade

Notes: Figures are in billion USD. HS code 870380 refers to: Motor cars and other motor vehicles principally designed for the transport of <10 persons, incl. station wagons and racing cars, with only electric motor for propulsion (excl. vehicles for travelling on snow and other specially designed vehicles of subheading 8703.10).

Source: Author’s Calculation on Import data from 2017 to 2021 using UN Comtrade

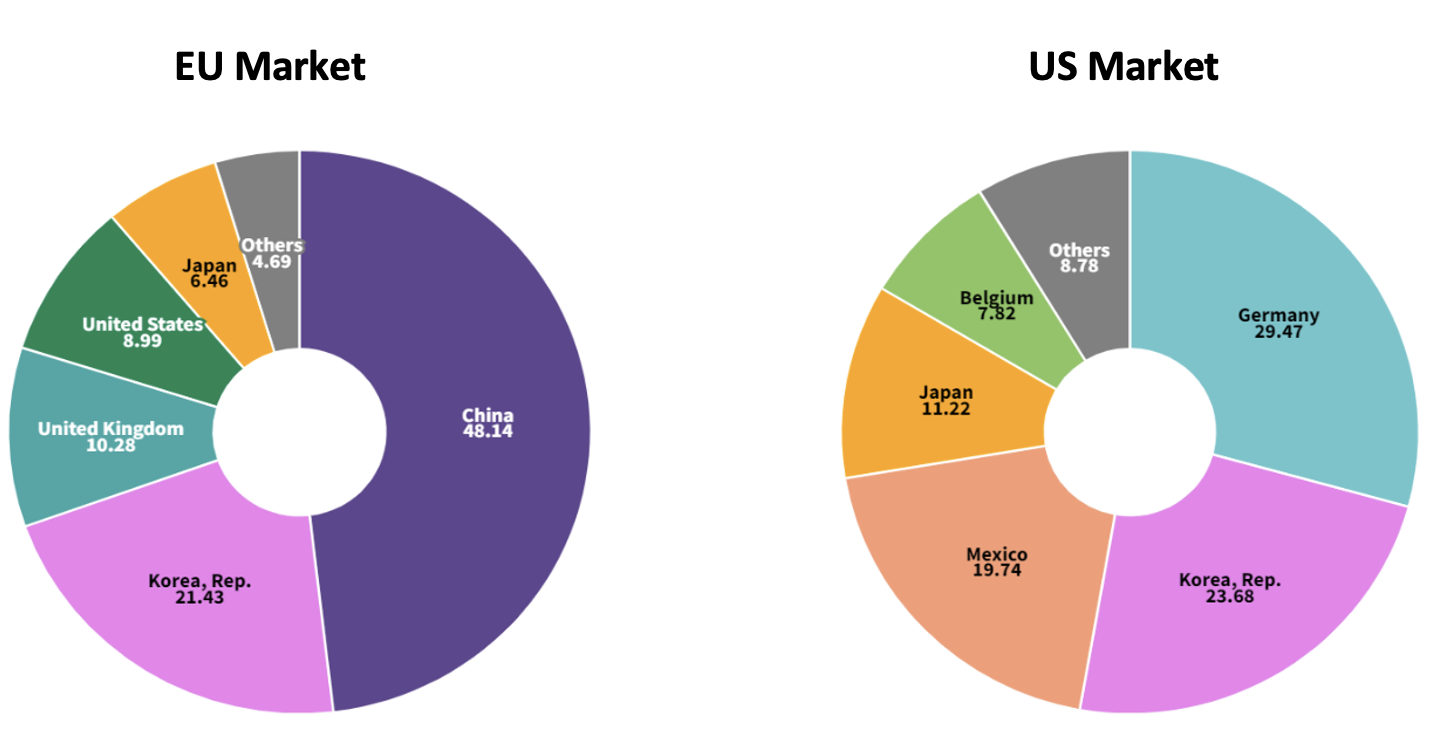

Whereas the EU has implemented tariffs on Chinese EVs in the face of a huge surge in imports, the United States has imposed even higher tariffs of up to 100% on Chinese EV imports despite minimal penetration of these vehicles in its market. Unlike the EU with its heavy reliance on China, the US has diversified its EV supply chain primarily through suppliers in Germany, Korea, and Mexico. This difference underscores how the EU’s approach is potentially consistent with addressing concerns about economic vulnerabilities and promoting local industry growth. In contrast, the US strategy focuses more on safeguarding its existing supply chain diversification.

Figure 2 shows the largest suppliers of EVs to the EU and US markets, respectively. We can observe how heavily reliant the EU is on China as the largest supplier of EVs by a wide margin, whereas the US has been able to diversify its supply chain sufficiently among other exporters.

Source: Author’s Calculation from UN Comtrade Data

Beyond the economic implications, China has complained that the EU duties contravene WTO rules. The WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement) provides the legal framework for these actions, allowing member countries to impose countervailing duties on subsidized imports harming domestic industries. While differentiating duties by firm is common in anti-dumping cases, it is less familiar in the context of subsidies. This differentiation might initially raise concerns about discrimination. Article 15(2) of Regulation (EU) 2016/1037 allows the EU to impose firm-specific countervailing duties. The SCM Agreement’s silence on this practice implies its likely permissibility due to the absence of an express prohibition.

Moreover, the EU’s regulation includes a separate procedure for calculating duties in cases of non-cooperation, potentially resulting in higher tariffs for such firms. Nevertheless, the basis for selecting specific Chinese companies under investigation remains unclear. Chinese firms receive various forms of support, including preferential interest rates, directed credit, tax credits, and cross-subsidies. The methodology for calculating tariffs has only been circulated to the sampled firms thus far. Until the EU publishes its methodology, it is difficult to fully assess the legal validity of the EU’s differentiated tariffs and how subsidies for each firm have been accounted for, as well as the injury to the EU industry caused by each firm.

The EU’s tariffs on Chinese EVs will have varied economic repercussions. They may serve as a catalyst for Chinese manufacturers to relocate production to the EU. For instance, Chinese carmaker BYD has established EV plants in Hungary, and Geely has shifted production to Belgium. This shift has the potential to attract investment, bolster local manufacturing, stimulate job creation, and enhance EU technological capabilities.

However, the immediate consequence of higher tariffs could be increased costs for consumers as part of the tariff rise will most likely be passed on to them. In addition, more protection for EU producers might shift their focus away from innovating and seeking efficiency gains. Finally, the tariffs may strain EU-China trade relations and prompt retaliatory measures.

Imposing tariffs on Chinese EVs may also jeopardize the EU’s ambitious climate goals, as outlined in the European Green Deal. Higher tariffs are almost surely set to slow down EV adoption rates in the EU, delaying the transition away from fossil fuel-powered vehicles and hindering progress towards achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Additionally, efforts to boost local EV production in response to tariffs may temporarily raise CO2 emissions during manufacturing, particularly in energy-intensive battery production. Striking a balance between trade policies and environmental objectives is crucial to ensure that measures such as CVDs support rather than hinder the EU’s carbonization progress.

As the US and EU pivot away from heavy reliance on Chinese manufacturing, they are integrating ASEAN nations (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) into their supply networks. These efforts are bolstered by frameworks such as the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)[1]. This strategic shift underscores the imperative of diversifying supply chains to enhance economic resilience amidst global uncertainties.

In this recalibration, cultivating strategic partnerships—often termed friendshoring—takes on critical significance. These alliances aim to deepen economic collaboration while mitigating risks associated with overreliance on single suppliers. As part of such initiatives, the EU may aim at strategically diversifying its EV supply chain by investing in economies such as Mexico, Japan, and South Korea, thereby enhancing supply chain resilience and reducing dependency on China. India, with its burgeoning EV market, represents a significant opportunity. Notably, in 2023, India surpassed China in three-wheeler EV sales, underscoring its potential as a key player in the global EV industry[2].

The EU’s impending tariff hike on Chinese EVs presents a complex challenge touching on economic, environmental, and geopolitical dimensions. While aimed at protecting European industries from unfair competition, these measures may strain EU-China relations and potentially undermine the EU’s climate goals. Balancing the need to diversify supply chains with environmental goals and political costs is crucial to mitigate risks and ensure sustainable economic growth.

[1] Neither the EU nor the US are part of CPTPP, even though the agreement is shaped on the provisions negotiated for the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP). This latter was heavily influenced by the US, although it withdrew from it in 2017 and CPTPP came into effect between 11 signatories in 2018. The UK signed an accession protocol in 2023.

[2] https://www.cnbc.com/2024/04/26/india-says-new-ev-policy-will-open-up-market-to-global-players-.html

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 28th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

June 25 2024

June 25 2024

Sahana Suraj is a UKTPO Research Fellow in International Trade.

With less than two weeks until the United Kingdom elects its 59th parliament, campaigning efforts by contesting political parties intensified with the recent publication of party manifestos.[1] The UK is the fourth largest exporter of goods and services, so it is particularly important to shine light on the next government’s stance for developing a robust trade policy that maximises the benefits of trade consistent with domestic policy objectives.

While clearly there is a degree of overlap, the approaches to trade (policy) by the main parties—Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats, Green Party, Reform UK—can be broadly categorised into three different groups.

One group, consisting of the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats, appears to align trade policy with industrial strategy. Concerned with building a resilient and secure economic future, their proposed course of action aims at capitalising on the UK’s existing economic strengths, including in services trade. This approach entails a focus on the depth and quality of agreements, forging strategic partnerships to create a pro-business and pro-innovation environment, and making trade more accessible.

This orientation to trade policy can be characterised as going beyond a conventional focus on Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). Labour, for instance, also recognises the importance of Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) and standalone agreements to promote services trade and digital trade. Agreements of this nature can have strong trade promotion effects and can be effective in reducing non-tariff barriers to trade. The Liberal Democrats have stressed the importance of human rights, labour rights, and environmental standards while negotiating trade deals. This indicates their commitment to using trade policy to achieve benefits in other areas of public policy. They propose renegotiating existing trade agreements with Australia and New Zealand to achieve more favourable outcomes for the UK in health, the environment, and in animal welfare.

Both parties are focused on promoting deeper cooperation in trade policy by expanding markets for British exporters and deepening trade partnerships. Labour also endorse the ongoing FTA negotiations with India and are open to negotiating agreements with the United States and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Moreover, they recognise the importance of African economies and multilateral institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Another group consists of manifestos whose approach to trade policy derives from their commitment to sovereignty above all. This includes the Conservatives and to a lesser extent Reform UK. They focus on the imperative for the UK to independently dictate its course on all trade policy matters, as well as protecting the UK’s internal market. The Conservatives propose heavy reliance on FTAs to extend ties to Switzerland, the Middle East (GCC, Israel), Asia (India, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia) and the United States, the rationale being an expansion of trading relationships post-Brexit. The aim of these agreements is largely to increase cooperation in trade, technology, and defence that will eventually allow the UK to become the largest defence exporter in Europe by 2030. These strategies exemplify their strong emphasis on linking trade policy with economic security.

As part of the focus on sovereignty, the Conservatives and Reform UK both assign importance to agriculture. Ending UK quotas for EU fishers, creating opportunities for the domestic food and drink industry, and recognising the importance of farmers while negotiating FTAs are issues raised by the parties. There are also detailed plans to promote intra-UK trade. While Reform UK proposes a rather radical approach by abandoning the Windsor Framework, the Conservatives recommend the establishment of an Intertrade body to promote Scottish exports and partnerships with British Overseas Territories.

Lastly, the Green Party’s stance on trade policy incorporates elements found in the preceding two groups with policies that encourage trade agreements to take account of worker’s rights, consumer rights, animal protection, and environmental standards, and a traditional focus on agriculture. They advocate the ending of what the party perceives as unfair deals related to food and agriculture and rather place emphasis on encouraging domestic food production.

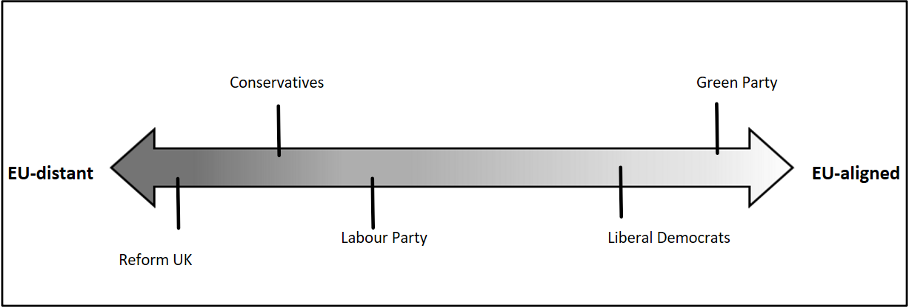

The question of the UK’s future relations with Europe is arguably of central importance from a trade perspective. On this aspect, the parties exhibit much greater divergence between each other, than their general stance on trade. Each of the parties proposes varying levels of engagement with the European Union as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Level of closeness to the EU as proposed by the parties’ manifestos.

Both main parties—the Conservatives and Labour—are against Britain’s return to the European Union. However, they differ on future trade relations with Europe. Labour advocates closer ties with the EU and wants to take advantage of Britain’s geographical proximity to the region. It intends to negotiate a mutual recognition agreement with European counterparts on professional qualifications and services exports. Labour is also in agreement with the EU’s approach to transition to Net Zero by adopting a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and they aim at negotiating a veterinary agreement with the EU to reduce the burden of border checks.

In contrast, the Conservatives place legal sovereignty above other interests and accept a gradually growing regulatory distance from the EU as a result. They are keen to repeal EU laws that have been transposed into UK law since Brexit and ensure that the EU’s commitments are met under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA). They intend to dub the UK as the largest net exporter of electricity and implement a new carbon import pricing mechanism by 2027.

The position towards the EU of the other parties—Green, Reform, and Liberal Democrats—fall at either end of the spectrum. While Reform staunchly advocates for a complete renegotiation of the TCA and seeks to distance themselves completely from Europe, the Green Party and Liberal Democrats propose an eventual re-integration into the European Union. The Liberal Democrats especially want to align the UK’s and EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) and also align the UK’s food standards with that of Europe.

From the outset, trade policy does seem to be on the agenda of contesting parties, albeit still considered in conjunction with Brexit. That being said, there is a significant degree of uncertainty attached to the UK’s future trade policy, as the main parties present starkly opposite proposals on EU relations. And yet, the UK is an open economy that relies on international trade for economic prosperity and jobs. Therefore, the next government’s approach to trade policy and trade governance will matter a great deal, and the more clarity voters have over the parties’ intentions, the better.

[1] Party manifestos can be accessed by visiting the following links:

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 25th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

18 June 2024

18 June 2024

Alasdair Smith is a UKTPO Research Fellow, a researcher within the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP), Emeritus Professor of Economics and Former Vice-Chancellor at the University of Sussex.

The 2019 General Election focused on the one issue of Brexit, and Boris Johnson’s victory enabled the UK to leave the EU. The evidence analysed by UKTPO and many others since then has confirmed the general expectation among expert economists at the time that Brexit would have negative economic effects. And recent opinion poll evidence is that a majority of voters think Brexit was a mistake.

To say that Brexit was a mistake does not imply it could or should be simply reversed. Yet, it is reasonable to expect the political parties to address the issue in their current election campaigns.

The Labour Party’s ambition for the future EU-UK relationship is set out in two paragraphs in their manifesto published on 13 June:

“With Labour, Britain will stay outside of the EU. But to seize the opportunities ahead, we must make Brexit work. We will reset the relationship and seek to deepen ties with our European friends, neighbours and allies. That does not mean reopening the divisions of the past. There will be no return to the single market, the customs union, or freedom of movement.

Instead, Labour will work to improve the UK’s trade and investment relationship with the EU, by tearing down unnecessary [my emphasis] barriers to trade. We will seek to negotiate a veterinary agreement to prevent unnecessary border checks and help tackle the cost of food; will help our touring artists; and secure a mutual recognition agreement for professional qualifications to help open up markets for UK service exporters.”

A firm commitment to stay out of the EU for the next Parliament is surely wise. The UK-EU relationship has been bruised by the experience of the last 8 years. Rebuilding the relationship will take time and patience, and the opportunity to solidify the long-term relationship lies some way in the future. The incoming government faces formidable challenges in many areas and even a long-term plan to rejoin the EU would be a diversion from more immediate priorities.

Since there is no plan to rejoin, it follows that a new government must indeed seek to “make Brexit work”. It’s also right to aim for the removal of any unnecessary border checks and other barriers to trade that have damaged the UK economy.

This is a more positive and less dogmatic approach to the UK-EU relationship than the Conservative manifesto whose main concern is to rule out “dynamic alignment” to EU rules and “submission to the CJEU [the Court of Justice of the EU]”.

Dynamic alignment means sticking to EU rules even when they change. There’ s a strong case for dynamic alignment in many areas, to create a climate of regulatory predictability in place of the regulatory uncertainty and instability of recent years. In any case, firms have to satisfy EU regulations for products they sell in the EU. In many important sectors of the economy (like chemicals and motor vehicles) that means virtually all their production has to meet EU requirements, so separate UK regulations are a deadweight cost.

The Labour manifesto’s red lines are clearly drawn: “no return to the single market, the customs union, or freedom of movement”. The political pressure for such clear lines is understandable. However, they will constrain the objective of reducing border checks and other barriers to trade.

The European single market (which encompasses some non-EU countries like Norway) is the regulatory framework which removes barriers to trade within Europe. Members of the single market adopt common regulations, common processes for assessing conformity with these regulations, and a common legal framework under the umbrella of the CJEU. Members of the customs union similarly have a common policy towards goods imported from non-member countries. Checks on trade between EU countries are unnecessary.

However, if the UK remains outside the single market and the customs union, checks on UK exports to the EU are necessary to make sure that EU rules are satisfied. It’s not enough for UK producers to satisfy EU rules – their products still need to be checked for conformity. However much trust and goodwill are built up with our EU partners and no matter how much alignment there is with EU rules, the scope for removing “unnecessary” barriers to UK-EU trade may be frustratingly limited in practice.

The main political barrier to UK membership of the single market is, of course, the additional single market requirement for the free movement of labour. But post-Brexit restrictions on labour mobility between the EU and the UK has had adverse effects in many important UK sectors: including business services, agriculture, hospitality, social care, and the creative industries.

It’s understandable that the Labour manifesto rules out free movement, but notable that it is silent on the recent EU offer on youth mobility: proposals which emphatically do not imply freedom of movement (not least because they involve visa controls). These proposals would restore to young Europeans in the UK and the EU some of what they lost as a result of Brexit, and would also help address some of the problems of the sectors most affected by Brexit. Surely an incoming government should take a more positive approach to the EU offer.

Opinion poll evidence is that a clear majority of the UK electorate favour a return to EU-UK freedom of movement. A new government may find the political constraints changing quite quickly, so that rejoining the single market becomes thinkable.

A manifesto commitment not to rejoin the single market applies to the next Parliament but doesn’t stop the government from preparing to rejoin in the following Parliament. The path to re-entering the single market would in any case be a long one, probably via the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) into the European Economic Area (the EEA). This path requires preparation and negotiation.

That preparation should include addressing the fact that the single market requires free movement of labour not free movement of citizens. The UK could develop rules for a regime in which EEA citizens are not unconditionally free to come to the UK but are free to relocate to the UK (with their families) in order to work.

The Liberal Democrat manifesto, in contrast to the Labour manifesto’s red lines, makes a positive commitment to rejoining the single market:

“Finally, once ties of trust and friendship have been renewed, and the damage the Conservatives have caused to trade between the UK and EU has begun to be repaired, we would aim to place the UK-EU relationship on a more formal and stable footing by seeking to join the Single Market.”

Realistically, the timetable suggested by these words could well extend beyond the 4-5 years of the next Parliament. In this case, the difference between the Labour and LibDem manifestos may be presentational, rather than real. The single market issue will not go away, even if it cannot be settled before another general election at which a proposal to rejoin the single market could be put to the electorate.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 18th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

23 April 2024

23 April 2024

Adriana Brenis is a Research Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory (UKTPO) at the University of Sussex Business School. She holds an MSc in Business, Finance and Economics and a PhD in Economics from the University of Sheffield. Adriana’s research focuses on international trade, economic policy analysis and innovation.

The UK government recently announced its plan to implement common user charges for imports coming into the country. This has generated some controversy and, just this week, rumours that the government may again suspend the introduction of elements of the new Border Target Operating Model (BTOM).

The common user charges, set at a flat rate of £10 or £29 per commodity line, are capped at 5 charges per consignment, resulting in a maximum fee of £145. These charges will be applied to low-risk products of animal products (POAO), medium and high-risk animal products, along with plants and plant products. Initially, they will only be collected at border controls in Dover and Eurotunnel starting April 30th. This is part of the new BTOM system, aimed at improving border procedures. The goal is to cover the expenses of running these border facilities while protecting the UK’s food supply, farmers and the environment from diseases that could come in through these routes.

This blog explores the significance of these ports in facilitating the importation of goods into the UK and examines the extent to which the announced charges may affect incoming shipments.

Our calculations suggest that the animal and plant products that could face common charges represent about £38 billion of imports into the UK, making up 6% of all UK imports. Among these, 5.8% represent animal products and 0.2% plant products. Table 1 shows that 78% of these ‘at risk’ imports come from the EU, while 22% are from other parts of the world.

| Products at risk | EU | Non – EU | Total |

| Animal | 28.68 | 8.18 | 36.86 |

| Plants | 1.22 | 0.24 | 1.46 |

| Total | 29.90 | 8.41 | 38.32 |

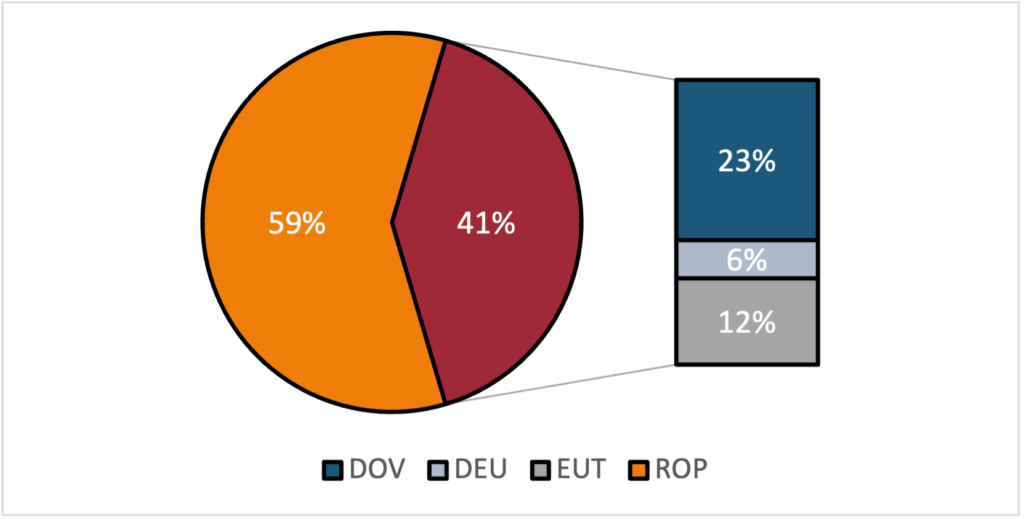

Given the substantial proportion of animal imports from the EU, we examine what share passes through the controlled borders – where the common user charges will be implemented starting April 30th. As illustrated in Figure 1, of the eligible animal products subject to charges (£28.7 billion), 41% (£11.7 billion) are imported through the controlled borders of Dover (DOV), Eurotunnel (EUT), and Dover/Eurotunnel (DEU), while the remaining 59% come through other ports in the UK (ROP). Among these, Dover stands out as the primary port for imports at 23%, followed by 12% via Eurotunnel, and 6% through Dover/Eurotunnel.

Source: HMRC and Animal & Plant Health Agency (2023)

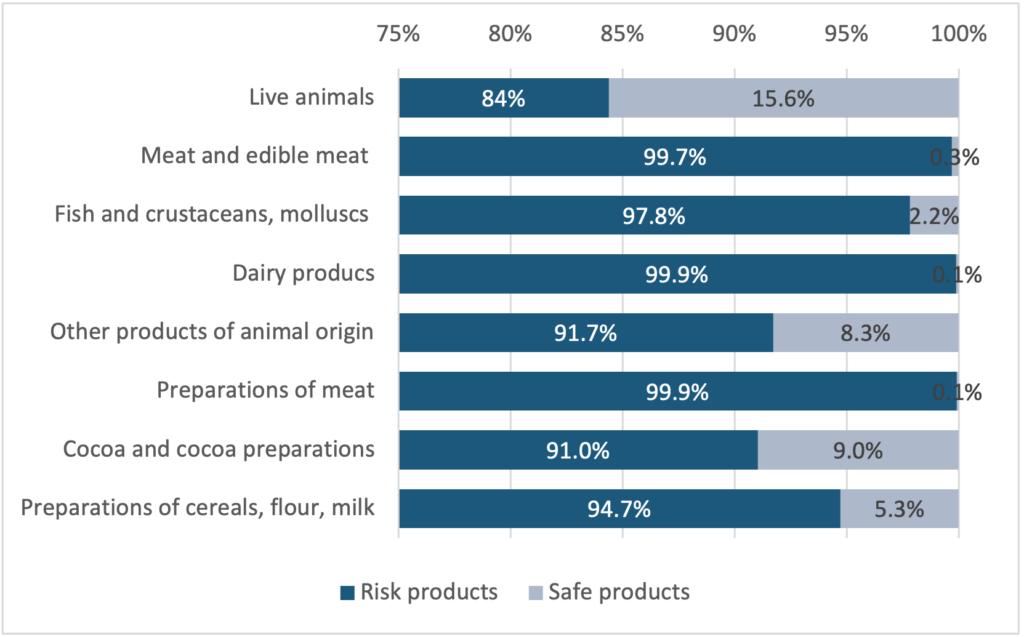

Among the different types of animal products classified under the Harmonized System (HS) at the 2-digit level, 31 out of the total number of 97 HS chapters have a percentage of animal products that could be subject to charges. Figure 2 highlights the HS classification at a 2-digit level, with the highest percentage of imported animal products at risk. Particularly, almost all imported products in HS 02 “Meat and edible meat”, HS 04 “Dairy products”, and HS 16 “Preparations of meat” are at risk. Other sections with more than half of their imported products at risk include HS 21 “miscellaneous edible preparations” (73%), and HS 23 “Residues and waste from the food industry” (75%). In addition, 91% of imported products in HS 18 “Cocoa and cocoa preparations” and 95% in HS 19 “Preparations of cereals, flour, starch or milk” could face charges, depending on whether they contain products of animal origin (POAO).

Source: HMRC and Animal & Plant Health Agency (2023)

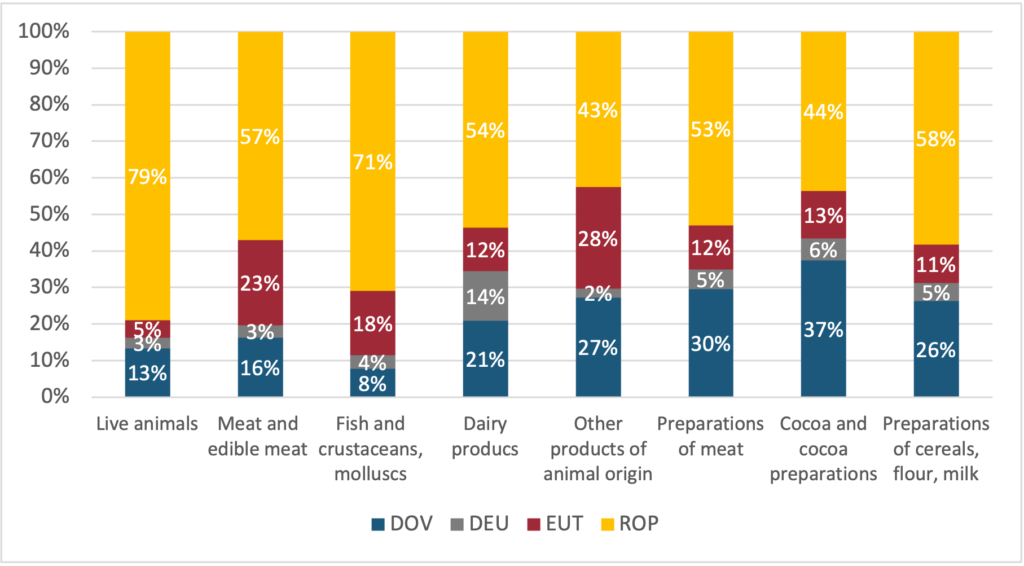

Focusing on the eight sections where most imports face potential fees, Figure 3 illustrates the share of the imports coming through the ports where charges apply. Live animals and fish, crustaceans and molluscs mainly come through other ports (79% and 71% respectively). In contrast, other products of animal origin primarily come through fee-charging ports, with Eurotunnel (EUT) at 28%, and Dover (DOV) at 27%. Similarly, cocoa and cocoa preparations products mostly enter through ports with charges, with 37% through Dover. Moreover, a large proportion of meat and edible meat (43%), dairy products (46%), preparations of meat (47%), and preparation of cereals, flour, and milk (42%) are brought in through these controlled borders with fees.

Source: HMRC and Animal & Plant Health Agency (2023)

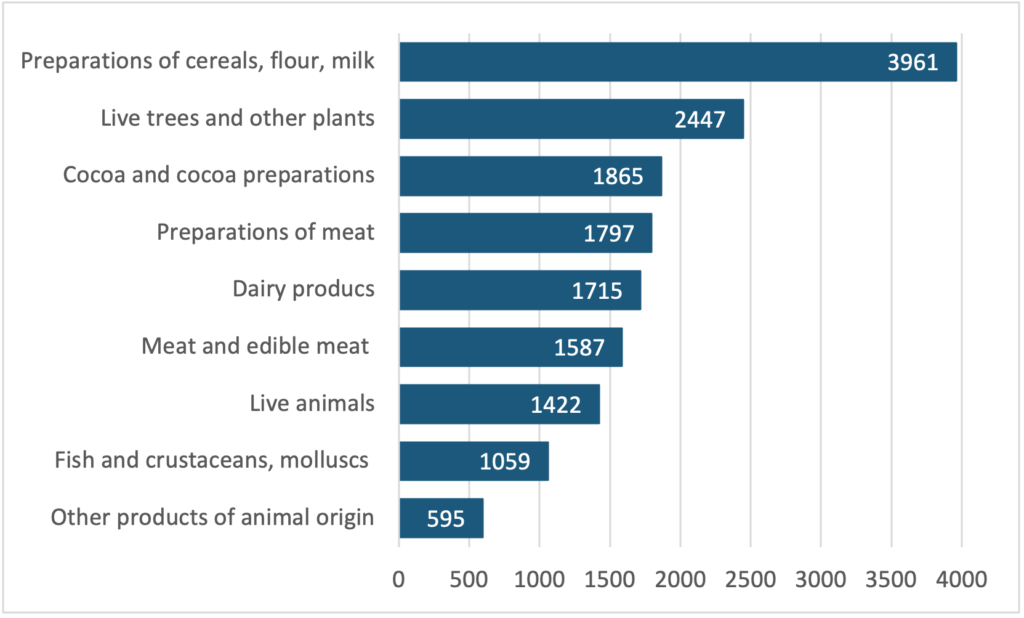

In 2023, out of the total Great Britain firms importing products globally (248,445 firms), those importing goods at risk from both EU and non-EU countries accounted for 16%, totalling 40,619 firms. Figure 4 provides the number of firms primarily importing within these eight categories, along with plant products from both EU and non-EU countries. The figure shows a significant number of firms fall within preparations of cereals, flour, and milk, followed by live trees and cocoa and cocoa preparations. As seen in Figure 3, these two categories – cocoa and cocoa preparations, as well as preparations of cereals – show a considerable percentage of imports arriving through the charged ports of Eurotunnel and Dover. Consequently, many of these firms could be affected by the upcoming common user charges starting on April 30th.

Table 2 provides a detailed view of the number of firms importing large amounts of animal and plant products within these categories. Considering the sections with high percentages of animal imports arriving through charged ports, like other products of animal origin and cocoa preparations, along with those with substantial imports (such as meat, dairy, and cereal preparations) are also, products like animal products n.e.s, including fresh cheese, pizzas, chocolate and other cocoa preparations, and sausages, which could be among the most affected.

Source: HMRC and Animal & Plant Health Agency (2023)

| 8-digi level | Name | Number of Firms |

| 01012100 | Pure-bred breeding horses | 859 |

| 02013000 | Fresh or chilled bovine meat, boneless | 390 |

| 03047190 | Frozen fillets of cod “Gadus morhua, Gadus ogac” | 101 |

| 04061050 | Fresh cheese “unripened or uncured cheese”, incl. whey cheese and curd | 258 |

| 05119985 | Animal products, n.e.s.; dead animals, unfit for human consumption | 351 |

| 06029050 | Live outdoor plants, incl. their roots | 761 |

| 16010099 | Sausages and similar products of meat | 609 |

| 18063100 | Chocolate and other preparations containing cocoa | 368 |

| 19059080 | Pizzas, quiches and other bakers’ wares | 1370 |

The introduction of common user charges for imports (especially for firms dealing with products subject to these fees) could have significant implications for both businesses and consumers. For firms, particularly those importing goods through charged ports, there may be a notable increase in operational costs due to the additional charges incurred. This could potentially impact their profitability and competitiveness. Additionally, firms may need to reevaluate their supply chain strategies, potentially exploring alternative ports or sourcing options to mitigate the impact of fees. Furthermore, the rise in costs could prompt changes in consumer behaviour, with some individuals opting for alternative imported products not subject to fees. Overall, the implementation of common user charges has the potential to reshape import dynamics, affecting both firms and consumers alike.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher April 23rd, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

23 February 2024

23 February 2024

Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Sunayana Sasmal is a Research Fellow in International Trade Law at the Observatory.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) dispute settlement system is in crisis. Here, and in a comprehensive working paper, we discuss one potential solution to one of the many issues confronting it. Non liquet is a legal principle that allows a tribunal to decline rendering a ruling when there is no law. We think this concept could partially address the major issue of judicial overreach. But first, some background.

Charlotte Humma February 23rd, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

16 February 2024

Michael Gasiorek is Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy. He is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Nicolo Tamberi is Research Fellow in Economics at the University of Sussex and Fellow of UKTPO.

Michael Gasiorek is Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy. He is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Nicolo Tamberi is Research Fellow in Economics at the University of Sussex and Fellow of UKTPO.

HMRC has just published statistics for trade in goods for December 2023, giving us three years of data after the implementation of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) with the EU in 2021. This blog reviews trends in UK trade with the world and the effects of the TCA on UK-EU trade.

There is good and bad news for UK trade in goods. Starting with the bitter pill, the UK’s trade in goods with the world has underperformed compared to other comparable countries over the last few years. Figure 1 shows the exports (panel a) and imports (panel b) of the UK, marked in red, and other OECD countries in blue, together with the series for the OECD total in dark blue. While during the period 2013-16, the UK was in line with the OECD total, the UK’s imports and exports started to slow down since the Brexit referendum in June 2016. For exports, the gap with the OECD total increased substantially with the Covid-19 pandemic. Imputing causation in this setting is not easy; most likely, the Brexit referendum, a slow recovery from the pandemic and the UK’s exit from the EU all contributed to the underperformance of UK trade. (more…)

Charlotte Humma February 15th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

4 January 2024

Guest author David Henig is Director of the UK Trade Policy Project at the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE). He has written extensively on the development of UK Trade Policy post Brexit, in the context of developments in EU and global trade policy on which he also researches and writes.

There was relief for Europe’s automotive sector at the start of December when the UK and EU agreed to maintain current product specific rules of origin for electric vehicles within the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) until the end of 2026. A scheduled intermediate stage of tightening on the way to even more stringent final rules to take effect from January 2027 was abandoned. Industry in both the UK and EU had been warning of potential 10% tariffs without an agreement and welcomed the move.

At the most basic level, this extension demonstrated that the UK and EU can find ways to improve their trading relationship. This had previously been shown with the agreement of the Windsor Framework to supplement the Northern Ireland Protocol to the Withdrawal Agreement, reached in February 2023, as well as full UK accession to the Horizon science research programme, scheduled to take effect at the start of 2024. Many commentators on both sides had doubted such progress would be possible at the start of the 2023.

With the TCA being the most valuable preferential trade arrangement to both the UK and EU, any indications of a better relationship should come as a relief. According to a November European Commission report “on the Implementation and Enforcement of EU Trade Policy”, in terms of EU preferential trade deals 22.5% of their value in goods is with the UK, rising to 46% for services. Meanwhile, despite the UK government’s aspirations for Global Britain, over 40% of its total trade remains with the EU.

Details of the negotiation and agreement over electric vehicles suggest however that it would be premature to expect plain sailing from this point onwards. There were suggestions in October that the broad principles of an extension for electric vehicles had been agreed, yet there were concerns on the EU side about whether this should be done legally inside the TCA or through a separate instrument. Final text which includes a prohibition of further extension showed a certain sensitivity in Brussels. In time this restriction could itself by renegotiated, but a marker not to do so has been laid.

For the EU, sensitivity is almost certainly based on their continued fears of a Brexit UK still expecting the market access of a Member State, in particular in areas of its specific interest. Experience was further that this attitude came with petulance and aggression from UK negotiators when not granted, in public and possibly to a degree inside negotiating rooms. These fears and memories should be of particular concern to a Labour Party committed to seeking TCA enhancements, particularly in terms of mutual recognition through agreements on food and drink, and professional qualifications. While the EU has shown a willingness to talk and does have its own interests, it should be obvious that no deal will be straightforward particularly if the EU is concerned about protection against future UK governments.

Meanwhile UK and EU automotive sectors face the challenge of being some way behind their Chinese competitors. For the time being, with this extension, and with the EU’s investigation into subsidies that may lead to countervailing duties, the industry is being given some time to catch up. There is clearly the expectation of this happening in the next three years, something which industry experts are already suggesting to be optimistic.

Extending and changing preferential trade agreements is never an easy matter, even between the friendliest trade partners. Particular circumstances of the UK-EU relationship make this even more difficult. Given such a background, one should probably see progress this year including on electric vehicles as being as good as it could get. That can perhaps be the foundation for a new approach, in a new year, and possibly even a new UK government, but they would do well to take nothing for granted.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher January 4th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

20 October 2023

Erika Szyszczak is a Professor Emerita and a Fellow of the UKTPO. She was the Special Adviser to the House of Lords Internal Market Sub-Committee in respect of its inquiry into Brexit: competition and state aid, and has previously acted as a consultant to the European Commission. She specialises in EU economic law. She is currently working with the European Judicial Training Network on developing training courses for national judges in EU competition law.

Erika Szyszczak is a Professor Emerita and a Fellow of the UKTPO. She was the Special Adviser to the House of Lords Internal Market Sub-Committee in respect of its inquiry into Brexit: competition and state aid, and has previously acted as a consultant to the European Commission. She specialises in EU economic law. She is currently working with the European Judicial Training Network on developing training courses for national judges in EU competition law.

On 3 October 2023 the Council and the European Parliament reached provisional political agreement on an Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI).[1] It is the latest legal trade measure contributing to the developing economic statecraft of the EU as part of the Open Strategic Autonomy. The tipping point for the EU to consider an extra method to address trade distortion occurred when China imposed trade restrictions on Lithuania after Lithuania improved trade relations with Taiwan. Lithuanian companies found that they could not renew or conclude contracts with Chinese firms, shipments were not being cleared and customs paperwork was held up. The ACI is portrayed as a deterrent device, discouraging third states from targeting the EU and its Member States with economic coercion through measures affecting trade or investment. It is another example of how the EU is forging a leadership role in developing new economic trade rules in a fragmented global trading world, by stealing a lead in the narrative on what is, and what is not, acceptable trade policy.

The European Commission proposed the ACI in the form of a Regulation on 8 December 2021 at the request of the Council and the European Parliament. The European Parliament Committee on International Trade adopted amendments to the proposal on 10 October 2022, and in the plenary session confirmed the Parliament’s negotiating mandate on 19 October 2022. The Council agreed its negotiating position on 16 November 2022.

The tipping point for the EU to consider an extra method to address trade distortion occurred when China imposed trade restrictions on Lithuania after Lithuania improved trade relations with Taiwan. Lithuanian companies found that they could not renew or conclude contracts with Chinese firms, shipments were not being cleared and customs paperwork was held up.

The Legal Base for the ACI is Article 207(2) TFEU:

“The European Parliament and the Council, acting by means of regulations in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure, shall adopt the measures defining the framework for implementing the common commercial policy.”

This is trade legal base for a measure designed to enhance EU economic and political resilience. The European Parliament Committee on International Trade adopted amendments to the proposal on 10 October 2022, and in the plenary session confirmed the Parliament’s negotiating mandate on 19 October 2022. The Council agreed its negotiating position on 16 November 2022.

The ACI defines economic coercion as when a non-EU country attempts to pressure the EU or a Member State into making a specific choice by applying, or threatening to apply, trade or investment measures. In the European Parliament Briefing ‘Proposed anti-coercion instrument’ different types of economic coercion are identified:

Once notified of an alleged act of economic coercion the European Commission must investigate within 4 months. The European Commission report will be sent to the Council which then has between 8 to 10 weeks to decide, by a qualified majority vote, whether the complaint of economic coercion exists. The first response will be to engage in dialogue to persuade the authorities of the non-EU country to stop the acts of economic coercion. If diplomacy fails, the EU has a range of countermeasures it can apply with the consent of its Member States. These include restrictions in trade of goods and services, intellectual property rights and foreign direct investment, imposing constraints on access to the EU public procurement market, capital market, and authorisation of products under chemical and sanitary rules. The European Commission has 6 months to set out the appropriate responses, whilst keeping the European Parliament and the Council informed at all stages.

The ACI is a new legal development in international trade law. It has been developed in response to activities deployed by China and the US which threaten EU security. The ACI is another example of how the UK, post-Brexit, may be the target of EU trade defence instruments.

Why does the EU need the ACI? The European Commission justifies the measure by arguing that new forms of economic coercion are not addressed by the existing conventional trade defence measures of the EU (for e.g. anti-dumping).

The concept of economic coercion set out in the ACI is not caught by current WTO rules. Even if the threatening behaviour could be brought within the existing WTO agreement, the stymied appellate process makes enforcement difficult.

However, the ACI is not a rapid defence trade mechanism. In fact, an EU firm or sector could suffer irreparable damage in the time it takes to activate and use the ACI. It may also encourage third countries to develop their own trade defence tools which are more effective than the ACI in responding to escalating situations.

[1] The European Commission proposed the ACI in the form of a Regulation on 8 December 2021 at the request of the Council and the European Parliament. EUR-Lex – 52021PC0775 – EN – EUR-Lex (europa.eu). The European Parliament Committee on International Trade adopted amendments to the proposal on 10 October 2022, and in the plenary session confirmed the Parliament’s negotiating mandate on 19 October 2022. Procedure File: 2021/0406(COD) | Legislative Observatory | European Parliament (europa.eu). The Council agreed its negotiating position on 16 November 2022. pdf (europa.eu). The Legal Base for the ACI is Article 207(2) TFEU: The European Parliament and the Council, acting by means of regulations in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure, shall adopt the measures defining the framework for implementing the common commercial policy.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher October 20th, 2023

Posted In: Uncategorised

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Michael Gasiorek is Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy. He is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Justyna A. Robinson is a Reader in English Language and Linguistics at the University of Sussex and a Director of Concept Analytics Lab.

Michael Gasiorek is Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy. He is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Justyna A. Robinson is a Reader in English Language and Linguistics at the University of Sussex and a Director of Concept Analytics Lab.

In early 2023, the Labour Party launched a National Policy Forum. It comprised a series of public consultations across six core policy areas, with the stated aim of helping the Labour Party to ‘build their policy platform’. A key part of the consultation process was to invite written submissions on these policy areas. One of the six policy areas was entitled Britain in the World, (to which the UKTPO/CITP also responded), which posed a set of seven questions all of which related to trade and trade policy.

The consultations were due to lead to a set of policy documents to be agreed in July 2023. With any consultation exercise, including those undertaken by the UK Government on the UK’s Free Trade Agreements, it is hard to know how seriously the consultation is being taken and which if any of the diverse views and responses are being listened to, and how selectively. Consulting with stakeholders and members of the public in the formulation of policy are important if taken seriously, and so consultations such as this are, in principle, welcomed.

So, on the eve of the Labour Party conference, we have analysed all the submitted responses to identify the key issues raised. There were 310 responses submitted which varied considerably in length. Most submissions were less than 500 words, but some were as long as 10,000 words. It is important to note that the consultation was open to anybody: individuals as well as organisations and companies. The chart below shows that 35% of the submissions were submitted by non-Labour party members (labour guests).[1]

Analysing the data is a challenge because the responses vary enormously in length and scope – with some private individuals submitting short sentences on a couple of issues, to larger organisations and companies submitting lengthy responses. Fortunately, there are tried and tested methods (and smart) software which provide a means for using corpus and natural language processing techniques for the analysis of such textual responses and controlling for different lengths of responses, so that individual lengthy responses do not dominate the analysis.

A key aspect of the analysis is to identify the frequency with which submissions raise particular issues. This is done by comparing the frequency of given words or groups of words in the submissions, relative to the frequency with which those words would appear in ‘normal’ usage. Hence words that appear relatively more frequently are those that prima facie raise issues that the respondents care about. In the jargon, this is called the ‘keyness’ score. We also need to control for the fact that certain terms may appear more frequently in individual responses. So, we want to be able to identify how often an issue is raised but to adjust for those issues being raised frequently in a small number of responses. This is done by producing something called the ‘average reduced frequency’ (ARF).

Consider the chart below. This gives the ARF score for the top 10 identifiable trade issues raised in groups of up to three words[2]. We see that the issue of trade and human rights is the primary concern, on average across the responses. Care has to be taken in interpreting the height of the bars – just because a bar is twice as high does not mean that the issue was perceived as twice as important. Nevertheless, it is clear that human rights were perceived as considerably more important than supply chains and economic growth.

Relatedly, if one takes the importance of individual words, the word ‘promote’ has a high ARF score. On its own, it is not clear what the respondents want promoting, and so we look at the collocation of words. This identifies that the key objective here was to promote growth, followed by rights, values, trade, and development in order of importance. Another word with a high individual score was ensure which co-occurs most with security (of supply chains), rights, and access (markets, supply chains), suggesting that these are of high importance for trade policy.

Of course, the frequency of some of these words will have been driven by the specific questions posed by the consultation exercise, as given above, which specifically asked about growth, supply chains and human rights for example. Even so, the rankings are significant as they indicate which of these issues appear of greater concern to respondents.

More depth in the analysis can be obtained by considering the nature of the responses to the individual questions posed. Hence, the responses pertaining to the role of international trade in promoting domestic economic growth, boosting jobs and driving up wages illustrate different perceptions of what trade policy is for. While some responses highlighted the role of trade in boosting productivity, innovation and access to supply chains, as well as emphasising trade with the EU; others focused on the role of trade (deals) in building relationships, soft power, and trust with third-party countries. Additionally, some demonstrated concern for objectives which are not focused on economic growth and economic efficiency such as the regional dimension, worker and human rights, or environmental protection.

With regards to the regional dimension, there is a clear message that international trade, especially services trade as well as ‘green’ trade, could and should be used to reduce regional disparities but that this also requires much more substantial investment in infrastructure and transport networks, as well as policies to mitigate negative impacts if it is to be successful. There was general acceptance of the importance of building more resilience in supply chains with a focus on the need to build trust with partner countries and reorienting supply chains to more trusted countries as well as protecting cyber-security. Interestingly, there was an overlap here with environmental and rights concerns with several respondents calling for more due diligence requirements in supply chains and moving to net-zero supply chains.

Environmental protection and cognate terms such as green technology, carbon emissions, energy, due diligence come up widely in the responses with widespread support for a better environment and net zero, even if it means renegotiating existing deals. Interestingly, the desire to use trade deals to lead to better outcomes in these regards does not pertain just to the UK, but that the trade deals should be used to influence and change practices in partner countries.

The responses highlight the importance of taking into account how trade may negatively impact a range of outcomes, be this with regard to the environment, regions, agriculture and animal welfare, older workers, disabled workers, or women. However, such concerns did not lead to opposition to trade deals, but rather to suggesting that (a) consideration of such impacts should form a (more) explicit element in the evaluation of proposed trade deals; and importantly (b) that there should be much more widespread inclusive consultation processes with affected groups, sectors, and regions in the formulation of trade policy and the negotiation of agreements.

Given the range of questions posed in the consultation exercise, it is perhaps not surprising that there is considerable heterogeneity in the answers. One clear message, however, which emerges is the recognition that trade is good for growth and an important element in raising productivity, but that at the same time, trade policy needs to be value driven. While these are not necessarily mutually exclusive there are trade-offs in trying to meet all the objectives. Hopefully publication of a trade strategy by the Labour Party may provide some insights on their approach to those trade-offs, and maybe the forthcoming conference may also shed some more light.

[1] Categories as defined by the Forum, see bottom of this page for all categories: https://www.policyforum.labour.org.uk/commissions/britain-in-the-world

[2] Note that we have excluded here terms that came up but do not, of themselves, shed meaningful light on trade issues, such as ‘UK government’ or ‘Labour Party’

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Charlotte Humma October 6th, 2023

Posted In: Uncategorised