by Dr. Felipe Antunes de Oliveira

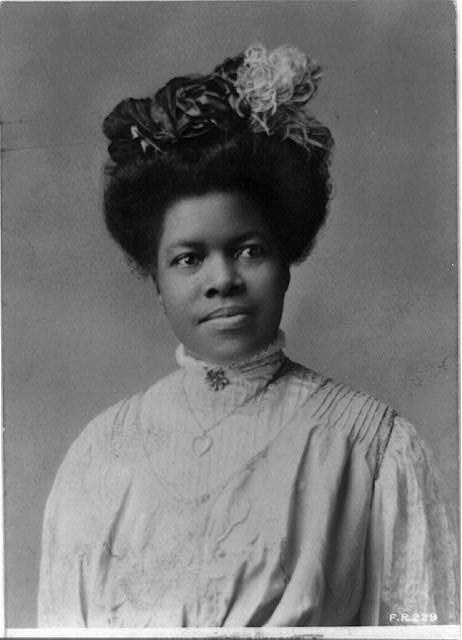

Image courtesy of Memorial Vania Bambirra (UFRGS)

The marginalisation of women’s voices in International Relations is a long-lasting and broad-based phenomenon, the full extension of which is only now being revealed by the WHIT project. However, as the case of Vania Bambirra shows, invisibility may be even starker when the condition of being a woman is compounded by the circumstance of being a Global South scholar espousing radical political ideas. Although some of Bambirra’s texts have been translated to German, Italian and Japanese, her most important writings are in Spanish and Portuguese, placing her beyond the imperial language barrier which has informally established English as the undisputed idiom of IR scholarship. Consequently, despite co-founding dependency theory, teaching at some of the most important universities in Latin America, and publishing dozens of highly original books and articles, Vania Bambirra’s name is completely absent from IR and IPE handbooks and disciplinary surveys.

Bambirra herself recounts her intellectual trajectory in a 100-page long academic memoir she wrote in 1991 as a requirement for reclaiming her position as Professor of Politics and International Relations at the University of Brasilia after returning from decades of political exile. Born in 1940 in Belo Horizonte, Brazil, she was first trained as a schoolteacher – a career she never intended to follow. In 1959, she was accepted at the Federal University of Minas Gerais for undergraduate studies in Sociology and Politics, soon also receiving a competitive scholarship to join a research team in Economics. Although Marxism was not officially part of the curriculum, Bambirra confesses that she spent most of her research time reading Marx, Engels, Lenin, Trotsky, Bukharin, Preobrazhensky and Rosa Luxemburg. Her studies were complemented by political activism in slums, trade unions and peasant associations, helping to establish the famous ligas camponesas (peasant leagues) – revolutionary agrarian reform movements that were precursors of the contemporary landless workers movement of Brazil.

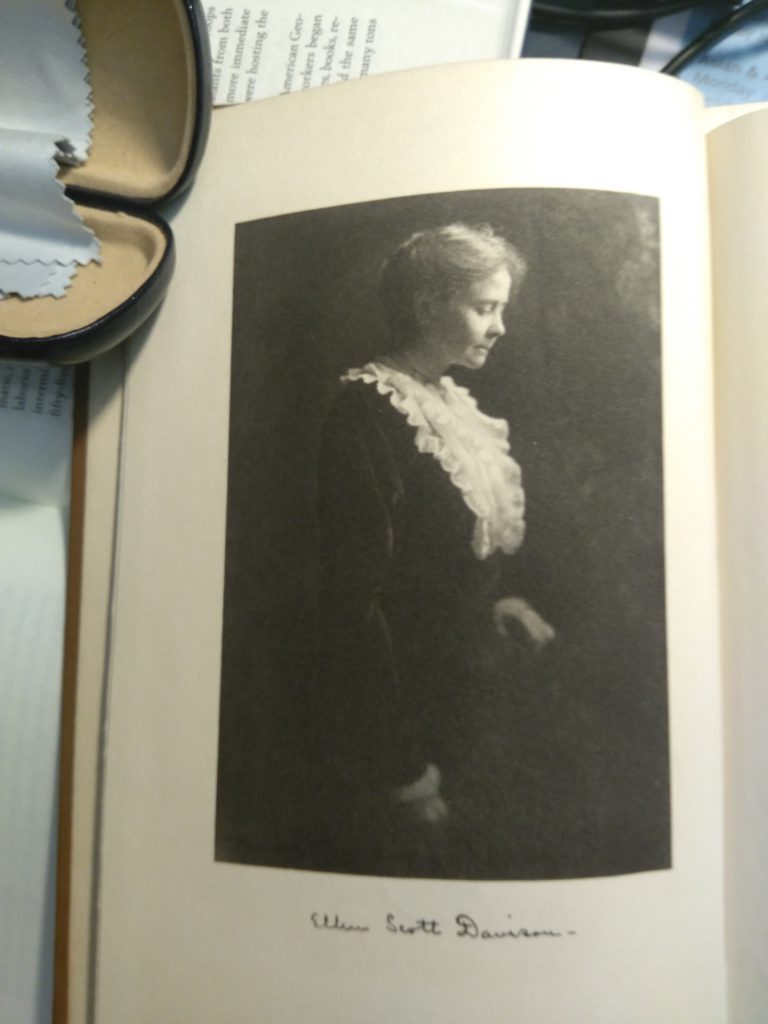

Image courtesy of Memorial Vania Bambirra (UFRGS)

In 1962, Bambirra was accepted as a master’s student and teaching associate at the newly founded University of Brasilia, created in the new Brazilian capital to be a centre for innovative social thinking. Because her husband was also accepted in the same department, the founder of the University and its first Dean, the revered anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro, proposed slashing her wages in half, so that the couple ‘would not get rich at the University’s expenses’. Refusing to accept the condition of a second-class academic just for being a woman, Bambirra mobilised her colleagues and founded the University of Brasilia Faculty Association – finally winning her arm-wrestle with the Dean and keeping her full salary.

After visiting Cuba as the representative of Brazilian social movements in 1963, a trip that included meetings with revolutionary leaders such as Ernesto Che Guevara, Bambirra returned to Brazil only to see her academic career abruptly interrupted by a right-wing military coup in 1964. In her memoirs, she recounts those turbulent days:

Consummated the coup, I returned to my office (…). It was very sad, literally. Everything that was in my shelves and my files (…) had been thrown to the ground, with obvious marks of boots soaked in the campus’ mud. My desk shelves were empty – not even the pens and a cheap necklace I left there remained in place. In sum, the chaos warned us: ‘don’t come back.’ Then I left, but not before going to the lecture theatre and reading the ‘Declaration of Human Rights’ to the students. It was an extremely sad farewell (Bambirra 1991, 21).

Hiding from the police, Bambirra moved to Sao Paulo, where her daughter was born under a false name to avoid political persecution at the hospital. In 1966, she finally managed to escape to Santiago, becoming a full professor at the University of Chile before her thirtieth birthday. After the 1973 coup staged by Pinochet against the democratic socialist administration of Salvador Allende, she was forced to flee again – this time, to Mexico, where she completed her doctoral studies under the supervision of Ruy Mauro Marini and earned a professorship at the National University of Mexico (UNAM).

In exile, her research would flourish and begin to attract international recognition. The only woman in the original group that created dependency theory, Bambirra published a highly original theory of revolution (1967, 1973), a caustic critique of Latin American ruling classes (1974; 1978) and an extensive analysis of the works of Marx and Lenin (with Dos Santos, 1981), as well as detailed historical case studies of the social, political and economic contradictions of Latin American societies (1977). Although Bambirra never saw herself as an IR scholar, her work has a strong international character, clearly building on Lenin’s theory of imperialism. In contrast with the simplified views of dependency theory popularised in North American universities by Gunder Frank and Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Bambirra’s writings explored the complex relationships between international pressures and social disputes in peripheral societies, refusing straightforward external determinism:

It is necessary to insist that the great theoretical contribution of dependency has been to demonstrate that this is not solely an international relations phenomenon, of trade exchange that is unfavourable to less developed countries; instead, it is the internal relations that conform a socio-economic structure whose character and dynamic are conditioned by imperialist subjugation, exploitation and domination (Bambirra 1974, 99).

Particularly interesting – and, so far, unexplored – is Bambirra’s engagement with the feminist ideas of the 1970s. Opposing a clear-cut separation between class struggle and gender-based oppression, she dismissed feminism as ‘an absurd and grotesque idea’ (1972, 84). Her problematic views on feminism were largely conditioned by the identification of the movement with the leadership of Global North, bourgeoise women. From her positionality as a Latin American political refugee, Bambirra realised that, across the Global South, bourgeoise women dumped the burden of housework on the shoulders of working-class women. For this reason, Bambirra classified ‘the petit bourgeoises woman in Latin America’ as ‘the most sinister exploiter that has ever existed’ (1978b, 40). As she explained:

The bourgeois woman, though it is true that she cannot escape her social category as object and her inferior position, does not experience the phenomenon of exploitation of her work in the home. On the contrary, she is served hand and foot. If she wants, she can work, whether in a career or for diversion. She exists to cultivate the trivialities of life, to show off the latest fashion, to adorn the house. Though woman, in general, occupies an inferior position, her problems are directly related to the class she belongs to. The bourgeois woman, even though her condition is that of an object, because she is a woman, does not have the problems of the proletarian, who lives the phenomenon of double exploitation in her work (Bambirra 1972, 83).

Several passages relating gender and class forms of oppression – often from a peripheral capitalist perspective – can be found in Bambirra’s published and unpublished writings. Overall, Bambirra’s sensitivity to varied and overlapping forms of oppression, as well as her deeply situated historical work, suggests that she may be seen as a precursor of intersectional IPE approaches. Ultimately, however, her firm commitment to historical materialism meant that class was normally taken as having ontological primacy over other analytical lenses.

Looking back at Bambirra’s rich academic and political trajectory, it is shocking that her work is never mentioned in disciplinary histories of IR and IPE. Particularly unforgivable is the failure of critical literature reviews of dependency theory to acknowledge her extensive contribution (Chilcote, 1974; Kaufman, Chernotsky, & Geller, 1975; Palma, 1978; Smith, 1979 –honourable exceptions are Cristobal Kay, 2010 and Grosfoguel, 2000). A case in point is Catherine Scott, whose book about gender and development (1995) raises important critiques of dependency theory. Based on a limited engagement with the dependency literature, the author claims that ‘[n]either gender nor women are explicitly discussed by the early dependency theorists’ (1995, 93). Although her critique of Cardoso and Faletto (1979) is certainly insightful, Scott’s sweeping assessment of dependency theory is fundamentally limited by her unawareness of the only woman in the original dependency group.

Revisiting Bambirra’s extraordinary life and work is particularly important at a moment when right-wing, authoritarian governments are again on the rise in Brazil and elsewhere. After Vania Bambirra’s death, in 2015, a dedicated group of Brazilian researchers digitalised most of her published and unpublished academic work and made it freely available on a website kept by the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul. A deep dive into Bambirra’s writings may reveal unexplored facets of her work; a comprehensive stocktaking of her contribution to IR, IPE, Latin American history and gender studies is still waiting to be written.

Dr. Felipe Antunes de Oliveira is a Research Associate at the Centre for Global Political Economy (University of Sussex) and Visiting Researcher at the Centre for Latin American Studies (Georgetown University).

References

Bambirra, V. (1967). Los errores de la teoría del foco. Santiago: Editorial Nuestro Tiempo.

Bambirra, V. (1972). Women’s liberation and class struggle. Review of Radical Political Economics, 4(3), 75–84.

Bambirra, V. (1973). La revolución Cubana: una reinterpretación. Santiago: Editorial Nuestro Tiempo.

Bambirra, V. (1974). El capitalismo dependiente Latinoamericano. Mexico DF: Siglo XXI.

Bambirra, V. (1977). Brasil: nacionalismo, populismo y dictadura: 50 años de crisis social. Mexico DF: Siglo XXI.

Bambirra, V. (1978). Teoría de la dependencia: una anticrítica. Mexico DF: Ediciones Era.

Bambirra, V. (1978b). The situation of Latin American Women – Interview with Vania Bambirra. Two Thirds – a journal of underdevelopment studies. 1(3), 38-42.

Bambirra, V. and Dos Santos, T. (1981) La estrategia y la tatica socialistas de Marx y Engels a Lenin. Mexico DF: Ediciones Era.

Chilcote, R. H. (1974). Dependency: A critical synthesis of the literature. Latin American Perspectives, 1(1), 4–29.

Grosfoguel, R. (2000). Developmentalism, modernity, and dependency theory in Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South, 1(2), 347-374.

Kaufman, R. R., Chernotsky, H. I., & Geller, D. S. (1975). A Preliminary Test of the theory of dependency. Comparative Politics, 7(3), 303–330.

Kay, C. (2010). Latin American theories of development and underdevelopment. London: Routledge.

Palma, G. (1978). Dependency: A formal theory of underdevelopment or a methodology for the analysis of concrete situations of underdevelopment? World Development, 6(7–8), 881–924.

Scott, C. V. (1995). Gender and development: rethinking modernization and dependency theory. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Smith, T. (1979). The underdevelopment of development literature: The case of dependency theory. World Politics, 31(2), 247–288.

Recent Comments