Section 1: Government Procurement After Brexit: The International Context

Section 2: Options for UK Public Procurement Law and Policy

This briefing paper looks at some of the legal issues that will affect the UK’s public procurement laws and policies following Brexit. For, once the UK revokes the European Communities Act 1972, it will no longer be obligated to follow the EU Procurement Directives, nor will it be subject to the commitments the EU has signed up to on behalf of the UK in the WTO Government Procurement Agreement (GPA) and in Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs). Additionally, under the Devolution Settlement of 1998, the competence for public procurement was transferred to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales; internal, centrifugal forces will therefore also impact on the design of the public procurement regime in the UK after Brexit.

Brexit could fragment government procurement policy within the UK, as well as disrupting the UK’s relationship with the WTO GPA and other preferential procurement agreements. This paper addresses these challenges and puts forward a response to some of the potentially negative consequences of Brexit that could undermine value for money, transparency and competition within the UK’s lucrative markets for government procurement contracts.

The sheer value of public procurement contracts make them important both economically and for providing society with essential public goods, services and infrastructure. China’s government procurement market totalled approximately $88 billion in 2008 – more than triple the amount in 2003. The EU’s procurement market was worth over €1500 billion – over 16 per cent of total EU GDP – in 2004, and grew to over €2150 billion in 2008.[1] In 2013/14, the UK public sector accounted for 33% of UK public sector spending [2] and 13% of GDP [3]– so ensuring good public procurement policy is beneficial to markets and taxpayers.

Currently, the UK’s procurement laws fall under the application of the EU’s 2014 Procurement Directives for Goods and Services, Utilities and Concessions. The EU has also negotiated the coverage of the WTO Government Procurement Agreement on behalf of all 28 EU Member States and various PTAs, most recently the EU-Canada CETA, which includes a comprehensive chapter of public procurement provisions.

The Great Repeal Bill aims to revoke the European Communities Act 1972 and to incorporate current applicable EU law into an Act of Parliament. Additionally, following the Devolution Settlement of 1998, certain competences – including public procurement – were devolved to Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. So, unless the laws affecting devolved issues are unilaterally scrapped by Westminster as a consequence of Brexit, the Great Repeal Bill will result in decentralising government procurement legislation. This could potentially fragment a coherent UK-wide procurement strategy towards the WTO GPA, as well as in its PTAs.

This paper assesses the legal challenges and opportunities for the UK’s public procurement laws and policies after Brexit. Section 1 briefly examines the issue of sequencing government procurement negotiations after Article 50 TEU has been triggered. Section 2 then examines the options open to the UK in the renegotiating of its procurement rules externally – at the WTO GPA and in its PTAs – as well as internally, in relation to the Devolution Settlement and decentralised procurement policy in Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

While the UK government can enter into informal discussions regarding its future trading arrangements – including public procurement – with third parties, the UK is unlikely to sign any agreements until it has withdrawn from the EU and repositioned itself with regard to the WTO and the EU itself.

First, to conclude a trade agreement with a non-EU party while the UK is still formally a Member State of the EU would be in breach of Article 3(1)(e) TFEU, which provides the EU with exclusive competence in determining common commercial policy on behalf of its Member States. Serious conflicts of interest would also likely surface, in breach of Article 4.3 and Article 24.3 TFEU. These laws obligate Member States to refrain from any action which is contrary from the EU. This is not a trivial point. Good faith is a fundamental principle of international law codified in Article 26 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties,[4] without which surely all international law would collapse.

Second, from a negotiator’s perspective the legal framework for negotiating a free trade agreement is primarily the WTO’s MFN exceptions, under Article XXIV GATT and Article V GATS. A prerequisite to repositioning the UK’s trade terms post-Brexit is therefore going to involve establishing the UK’s MFN commitments under the GATT and GATS, with all the other 164 or more Members – including the EU. Some commentators have argued otherwise – that the UK is already a WTO Member with independent rights and obligations, including those relating to its MFN coverage in goods and services.[5] This seems an optimistic and overly simplistic interpretation in the case of services under the GATS schedules, where the UK’s commitments are set out both independently and jointly with the EU. The UK will need independently to set out its GATS Schedule whether or not it is certified by other WTO Members, because the UK needs a schedule upon which to trade.[6] So, it is not until the UK has formally determined its MFN coverage under the WTO that the UK can seek to negotiate a more favourable trade agreement in accordance with the WTO’s MFN exceptions under the GATT Article XXIV and GATS Article V.

The UK is currently a signatory party to the 2014 Revised WTO GPA through its membership of the EU. It has not had to ratify this agreement as an individual party. The total value contracted by the 27 Member States of the EU and covered by GPA in 2012 was €283.4 billion.[7] The UK accounts for 84% of the total value procured at EU level in awards of more than €100 million.[8] The US Government Accountability Office estimates the value of the EU’s total procurement markets to be US$1.6 trillion, the US’ total procurement market at US$1.7 trillion, and the aggregate value of the other WTO GPA parties at US$1.1 trillion.[9]

After Brexit, the EU will need to remove the UK’s coverage from the EU’s WTO GPA schedules by notifying the other parties to the WTO GPA of any proposed modifications to their commitments, pursuant to WTO GPA Article XIX. The removal of the UK schedules will create a gap in the value of the EU’s schedules and the EU will need to modify its schedules and market access commitments on the basis of reciprocity. Alternatively, they must compensate the other parties to the WTO GPA on the loss of coverage follow the UK’s detachment, pursuant to Article XIX WTO GPA covering modifications and rectifications to coverage. This provision requires, among other things, notification to the Committee of any proposed modification of its annexes to Appendix I, along with information as to the likely consequences of the change for the coverage provided for by the WTO GPA.

Valuing the UK’s procurement coverage separately from the EU is not straightforward. First, there are elements of the UK’s coverage that are tied into the EU’s procurement schedules. For example, under the WTO GPA Annex 2 the EU’s sub-central government entities coverage for regional or local contracting authorities, sets out indicative rather than clearly defined coverage for each Member State.[10] Second, parties to the WTO GPA cannot commit procurements for services under the WTO GPA Annexes unless these services markets have been opened up under the GATS schedules. So, before the UK can negotiate its own coverage under the WTO GPA, it needs to reset its MFN commitments in GATS schedules. Among the nine parties currently acceding to the WTO GPA are Australia, China and Russia, while India, for example, is an observer. Should the UK wish to influence these significant trading partners’ market access negotiations before they join, it would be wise for the UK to accede before these parties.

The WTO GPA depends on highly complex bilateral negotiations between the different Parties because a Party is not required to give the same commitments to all trading partners.[11] The WTO GPA Annex negotiations are based upon four basic variables: i) the value of procurement¬ – covering only contracts estimated to exceed a certain value threshold; ii) the identity of the procuring entity – covering only those listed by each party in its annexes; iii) the type of goods or services procured – consisting of all goods, apart from some expressly excluded by each party, and only services listed by each party in its annexes; iii) the type of goods or services procured – consisting of all goods, apart from some expressly excluded by each party, and only services listed by each party in its annexes; and iv) the origin of the goods or services – including only countries that are GPA parties.

Currently, as a party to the WTO GPA, the EU opens up all procurement above specified value thresholds, which is already covered by the EU directives. However, this coverage is highly qualified bilaterally, depending on the level of reciprocity. Significantly, the EU did not negotiate carve-out protections from the WTO GPA’s obligations for SMEs and nor did the EU aim to negotiate concessions that matched the SME objectives of other parties. This is because the internal EU (then, the European Community) procurement directives were promulgated to liberalise the internal market among its Member States. The rationale and principles embodied in the Procurement Directives are historically based on trade liberalisation.[12] So EU negotiators sought instead to explicitly penalise the US, Korea and Japan for discriminating in favour of their SMEs in procurement contract awards.[13]

The UK’s public procurement policy has been historically directed towards promoting competitive, commercial public purchasing. The UK government has singled out particularly uncompetitive public procurement markets such as communications networks, for example, because of their high barriers to entry for new businesses, economies of scope and scale, network effects, and technical gateways or bottlenecks that may give their owners market power.[14] Overall, the UK has been seen to have played a positive role in shaping EU procurement rules along commercial rather than bureaucratic lines.[15]

Yet, prior to implementing the EU procurement directives, the UK did not have a significant body of public procurement law or legal rules. Rather it relied in the main on administrative guidance from the Treasury for specific purposes, such as promoting value for money and controlling corruption in procurement processes. It was through the transposition of the EU Procurement Directives that a more legal approach was introduced into UK procurement practices. So to the extent that the objective of EU public procurement law is to open up the internal procurement market to tenderers from all other Member States, this transposition has introduced greater competition and promoted value for money – in line with previous UK procurement policy.

After Brexit, a pragmatic short-term solution would be to retain current regulations for the award procedures under the Great Repeal Act, but without conferring their benefits to suppliers from third parties without reciprocal arrangements. The freedom from the imposition of EU Procurement Directives will have implications for the UK’s internal procurement policy. As a consequence of the devolution settlement of 1998, public procurement became an area of responsibility for the devolved governments of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Following Brexit, the different parts of the UK will no longer be forced to apply the same public procurement rules, and different policy objectives are likely to appear in the award of procurement contracts, promoting different local economic development and social goals.

The value of procurement in the different areas and sectors is also varied. Table 1 sets out the total budget broken down into different departments. The National Health Service is by far the biggest spender of the procurement budget, with more than double the share of defence. Table 1 highlights the relative significance of procurement spent by Northern Ireland, Scotland, and Wales. This decentralising dynamic could undermine a coherent public procurement law and policy at the UK level, as well as transparency, competition and value for money.

Table 1: Total Procurement in £m Budget by Department (HM Treasury 2012)*

In 2013/14, the UK public sector spent a total of £242 billion on procurement of goods and services. There is political pressure to use this sum to pursue a variety of public policy aims, such as promoting small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) or encouraging local growth. Indeed, both of these objectives were stated aims of the UK’s coalition government of 2010-2015, which in 2013/14, set a target for central government to procure 25% of goods and services by value from small and medium-sized enterprises. The 2015 Conservative manifesto included a pledge to increase the percentage spent with small and medium-sized enterprises to a third.[16]

Following Brexit, when negotiating its accession terms to the WTO GPA the UK has the option of avoiding the current legal impasse the EU has encountered when promoting SMEs though government procurement contract awards. If the UK so chooses, it can establish a comprehensive policy framework to promote SMEs, in line with other signatory parties such as the US, Japan and S. Korea. The UK could negotiate specific carve outs for its small medium-sized enterprises, for example, for this would provide the legal discretion for and Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales to pursue such policies, while maintaining a coherent UK procurement framework to pursue in trade agreements.

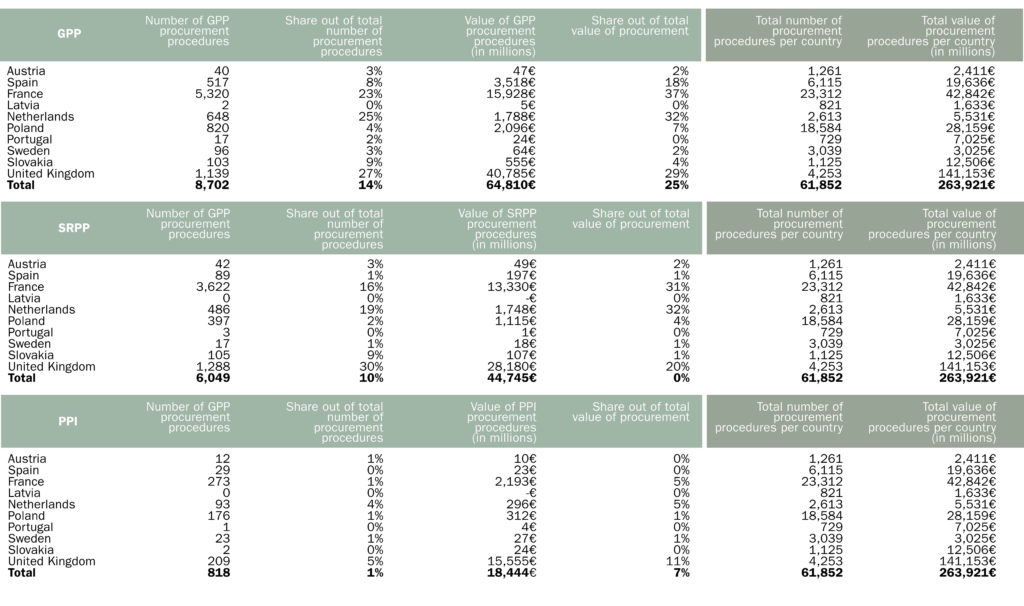

There are various other policy objectives that the devolved regions of the UK may also choose to pursue through public procurement awards. A 2013 study based on EU Tender Electronic Data (TED)[17] assessing the use of public procurement for promoting the environment – or green public procurement (GPP), social responsible public procurement (SRPP) and public procurement for innovation indicates that the UK is the leader in all three categories. (See Table 2)[18] However, recent WTO disputes indicate that procurement policies promoting industrial or environmental policies are actionable under various multilateral agreements, even if they have been exempted from the WTO GPA commitments.[19] The UK will need to ensure that horizontal policy objectives implemented through devolved procurement awards are in compliance not only with the WTO GPA, but also under other multilateral rules including the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures, the GATT, GATS and the TRIMs.

Table 2: The Estimated Magnitude of Strategic Public Procurement in Number/Value by Member State

Source: Strategic use of public procurement in promoting green, social and innovation policies.” Final Report DG GROW Framework Contract N° MARKT/2011/023/B2/ST/FC for Evaluation, Monitoring and Impact Assessment of Internal Market DG Activities.

Ensuring non-discriminatory, transparent and fair public procurement is seen as the best way for citizens and tax-payers to obtain the best public goods and services available, and at the best value for money. To achieve this, procurement markets need competition. One way to facilitate this is to bring the competition authority and the procurement agencies closer together. There has been a tendency to perceive government procurement laws as largely focused on establishing the contractual arrangements for buying public goods and services. Competition law, on the other hand, has been seen as being largely focused on addressing private restraints of competition that prevents markets from being contestable and damaging to consumers. This approach is evident in the UK, where the Crown Commercial Services (CCS) is responsible for implementing the legal framework for public sector procurement and leads on the development and implementation of procurement policies for government.[20] Competition law, on the other hand, is enforced by the UK Competition and Markets Authority.[21]

Under this separated perspective, very limited interaction is envisaged between competition and government procurement law. The two bodies of economic regulation seem to have different objectives and consequently seem to offer weak reasons for their joint study or for the development of consistent rules and remedies.[22] Yet, from an economic perspective, competition principles are generally applicable to public procurement. They can be seen most obviously in the area of bid rigging and collusion amongst tenderers for public contracts.[23] The complexity of competition effects from procurement means that the public sector can both promote and restrict competition – either by helping firms to overcome barriers to entry or by adopting procurement practices that restrict participation or discriminate against particular firms.[24] The interdependent nature of competition and procurement laws also emerges in the impact of subsidies/State aid in public procurement markets. Such factors contribute to determine the competitiveness of markets where the public buyer sources goods, works and services, and can thus constrain their ability to obtain to obtain allocative efficiency and value for money.

In the EU, Article 101 TFEU sets out the targets of competition law in two stages with the term undertaking. Any entity engaged in an economic activity that consists of offering goods or services on a given market, regardless of its legal status and the way in which it is financed, is to be considered an undertaking. No intention to earn profits is required, nor are public bodies by definition excluded.[25] In effect, this term is used to describe nearly anyone that is engaged in an economic activity,[26] except employees [27] and public services based on “solidarity” for a “social purpose.” A public undertaking, on the other hand, is an undertaking over which public authorities directly or indirectly exercise dominant influence by virtue of their ownership, financial participation, or the rules that govern it.[28]

However, the boundaries between competition and procurement blur because the objects of EU procurement law and competition law are similar and complementary.

The principal objective of the procurement rules is “the free movement of services… and the opening-up to undistorted competition in all the Member States.” The Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) also issued a revised interpretation of the concept of an undertaking for the purposes of the application of EU competition law to encompass economic agents engaging in a combination of both economic and non-economic activities.[29] In the EasyPay case, the CJEU determined that an activity will be considered as economic – unless it has links with another activity that fulfils an exclusively social function – based on the principle of solidarity and entirely non-profit making. Moreover, such an activity must, by its nature, aims and the rules to which it is subject, be ‘inseparably’ connected to its social function.[30]

The EasyPay Judgment was significant in departing from existing case law [31] to confirm that for the purposes of the application of EU competition law, an undertaking is any entity – even a procurement agency – engaged in an economic activity, irrespective of its legal status and the way in which it is financed. And further, that any activity consisting in offering goods and services on a given market is an economic activity.[32] Of additional relevance here is the 2014 High Court in England ruling on the application of the UK competition rules to tender design of an exclusive concessions contract tendered to Luton Operations to run a bus service between the airport bus terminal and central London.[33] In this case, the contracting authority was found to have abused its dominant position by negotiating a seven-year deal with the successful bidder when there would have been sufficient capacity for a second operator after three years. The long exclusivity generated a higher return for Luton Operations, which was held to be bad for consumers and an abuse of dominance in the buying market.

The UK could choose to reinforce a competition approach to public procurement and house it directly under the supervision of the competition authority. Supervision activities could be orientated towards preventing illegal awards of contracts. Precedents exist, for example, in Sweden the Public Procurement Act of 2010 provides the Swedish Competition Authority the possibility to take cases of illegal direct award of contracts to court. A company that infringes the Competition Act also risks being debarred from bidding for procurement contracts. Likewise in the Czech Republic, the Office for the Protection of Competition is the central authority of state administration responsible for creating conditions that favour and protect competition, supervision over public procurement and consultation and monitoring in relation to the provision of state aid. For the UK to follow such an integrated approach would be beneficial, to both open procurement markets, and for legal clarity and enforcement.

Promoting this integrated approach to implementing competition and public procurement law and policy may also be helpful in counterbalancing the centrifugal forces of devolution, undermining the benefits of competition in public procurement. For example, this could involve centralised monitoring of horizontal policy objectives through procurement awards in the different regions of the UK, following a similar assessment and surveillance system. This would also provide a more transparent, coherent and competitive framework for potential bidders, which would be of particular benefit to SMEs that wish to enter these lucrative markets. Currently, the EU has one of the most developed State aid control systems in the world. The UK is likely to continue to apply some form of State aid control following Brexit. Providing the UK competition authority with the mandate to oversee the monitoring and enforcement of competition law, State aid control and public procurement rules would help to ensure that decentralised legislation conforms to WTO commitments towards non-discrimination and subsidy control. Such centralised supervisory powers could also act as a counterweight against legal fragmentation, which could disproportionately undermine economies of scale as well as the benefits of competition and value for money in public procurement following the devolution of these competencies.

Brexit could therefore offer the UK the possibility to craft a procurement system flexible enough to incorporate the devolved procurement legislation, under the supervision of the Competition and Markets Authority. The UK could design a more simplified and flexible legislative framework in place of the over-cumbersome procurement rules currently spread over several EU Directives, with over-bureaucratic award procedures and relatively expensive legal enforcement mechanisms.[34] This streamlined regime would still be in compliance with the framework established under the WTO GPA.

This briefing paper has examined the sequencing of negotiations that need to take place before the UK can sign procurement agreements either within the WTO GPA, or agree new FTAs be they deep or shallow. Even if, optimistically, the UK can sidestep the issues involved in separating its schedules under the GATS from those of the EU, and can maintain its existing MFN commitments, it will still need to formally reset these with the WTO membership before it can seek to negotiate its accession to the WTO GPA, or other preferential trade agreements. These negotiations will involve the EU and could be protracted and highly politicised, particularly if the UK breaches its good faith obligations towards the TFEU before it detaches its Membership.

If the UK were to recast its procurement procedures under the framework of the WTO GPA’s minimum standards template, it would still have some flexibility to simplify and unify its procurement rules, as well as to formally exempt certain sectors, such as SMEs, from coverage of the commitments. However, this greater freedom to pursue horizontal policy objectives could also lead to greater divergence between the different devolved procurement legislation in the UK, as a consequence of the devolution settlement of 1998. Such increased regional diversity could operate to undermine competition, transparency and value for money within UK public procurement markets, as well as detracting from a strong and unified external negotiating strategy.

One way of checking and balancing some of these developments is to establish cooperation and coordinated measures to foster competition and value for money in public procurement policies. This could include, at the limit, integrating the competition and public procurement agencies together within a single agency competent to address anti-competitive practices such as bid rigging, merger control and State aid, which affect both open and public procurement markets across the UK. This agency could monitor and supervise regional horizontal policy objectives, such as SMEs or sustainable development, in public procurement processes. This would provide some centralised coordination to assess whether such measures are proportionate to their stated objectives and ensure that they do not undermine the very policy objective they intend to meet. Centralised surveillance mechanisms could also assess whether such measures are legally compliant with international and regional trade and procurement obligations.

This briefing paper therefore concludes by hoping that what could be a relatively straightforward discussion concerned with improving transparency, competition and value for money when awarding public procurement contracts, is not overshadowed by complex sequencing of negotiations, intra-UK jurisdictional divergences, and intractable political legacies with the EU.

This document was written by Kamala Dawar, University of Sussex Law School. The author acknowledges the useful comments from members of UKTPO, particularly Alasdair Smith, as well as Albert Sanchez Graells and J.H. Mathis.

Kamala Dawar asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this publication. Readers are encouraged to reproduce material from UKTPO for their own publications, as long as they are not being sold commercially. As copyright holder, UKTPO requests due acknowledgement. For online use, we ask readers to link to the original resource on the UKTPO website.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Benchmarking Public Procurement. 2016. World Bank Group. Available at: http://bpp.worldbank.org/~/media/WBG/BPP/Documents/Reports/Benchmarking-Public-Procurement-2016.pdf

[2] Lorna Booth. Public Procurement. House of Lords Briefing Paper Number 6029, 3 July 2015.

[3] Department for Business, Innovation and Skills) (2012a) No Stone Unturned in Pursuit of Growth. BIS, London. Cited in Barbara Morton, Gregg Paget, Carlos Mena. What role does Government procurement play in manufacturing in the UK and internationally and how? Cranfield University October 2013. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/283898/ep24-government-procurement-manufacturing.pdf

[4] Article 26. Pacta Sunt Servanda Every treaty in force is binding upon the parties to it and must be performed by them in good faith. Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. 1969.

[5 ] L. Bartels. The UK’s Status in the WTO after Brexit (September 23, 2016). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2841747

[6 ] P. Eckhout. House of Commons Briefing Paper: Brexit: the options for trade. ¶192.

[7] This is approximately £85 million. Albert Sanchez Graells. Written evidence for UK Parliament. (TAS0083) http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/eu-internal-market-subcommittee/brexit-future-trade-between-the-uk-and-the-eu-in-services/written/44483.pdf

[8] Albert Sanchez Graells. Id.

[9] The United States and European Union are the Two Largest Markets Covered by Key Procurement Related Agreements. Report to Congressional Requesters. US Government Accountability Office. GAO-15-717. p1.

[11] The coverage of the Agreement is set out for each signatory party in Appendix I, which is divided into Annexes concerning the specific coverage of the obligations. The Annexes address: 1) central government entities covered by the Agreement; 2) covered sub-central government entities; 3) “other” covered entities (e.g. utilities); 4) goods; 5) services coverage; 6) coverage of construction services; and 7) General Notes.

[12] For discussion, see S. Arrowsmith, ‘The Purpose of the EU Procurement Directives: Ends, Means and the Implications for National Regulatory Space for Commercial and Horizontal Procurement Policies’ (2012) 14 Cambridge Yearbook of European Legal Studies 1-47.

[13] https://e-gpa.wto.org/report/coverage

[14] Department of Trade and Industry Report (2000, December) ‘A new future for communications’. HMSO, London.

[15] For example, in the provisions on framework agreements and competitive dialogue introduced in 2004 and in the introduction or adoption of measures that were of concern to the UK in the 2014 reform process such as the “mutual” exemption and wider use of award procedures involving negotiation. See: Sue Arrowsmith. Brexit Whitepaper: The implications of Brexit for the law on public and utilities procurement. Achilles Briefing paper 2016. https://www.achilles.com/images/locale/en-EN/buyer/pdf/UK/sue-arrowsmith-brexit-whitepaper.pdf

[16] Crown Commercial Services. Procurement Policy Note – Reforms to make public procurement more accessible to SMEs Information Note 03/15 18th February 2015. Available at: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/405020/PPN_reforms_to_make_public_procurement_more_accessible_to_SMEs.pdf

[17] “Strategic use of public procurement in promoting green, social and innovation policies” Final Report DG GROW Framework Contract N° MARKT/2011/023/B2/ST/FC for Evaluation, Monitoring and Impact Assessment of Internal Market DG Activities.

[18] A caveat with these figures is the variable quality of information in the different Member State’s TED files.

[19] Appellate Body Report, Canada – Measures Relating to the Feed-In Tariff Program, 6 May 2013, WT/DS412/AB/R and WT/DS426/AB/R, ¶1.31. Report of the Appellate Body. India – Certain Measures Relating to Solar Cells and Solar Modules AB-2016-3 Report of the Appellate Body. WT/DS456/AB/R. 16 September 2016 ¶5.32.

[20] The implementation of the Public Contracts Regulations took effect from February 2015. See www.gov.uk/government/organisations/crown-commercial-service

[21] The CMA derives most of their powers from the Enterprise Act 2002 and the Competition Act 1998. See: www.gov.uk/government/organisations/competition-and-markets-authority

[22] Albert Sánchez Graells. “Public Procurement and State Aid: Reopening the Debate?” 21(6) Public Procurement Law Review. 2012:205-212.

[23] Weishaar, S.E., Cartels, Competition and Public Procurement. Edward Elgar. June 2013.

[24] See for example, Laffont, J-J. and J. Tirole (1994) A Theory of Incentives in Procurement and Regulation, MIT Press, London. They contend that procurement is a special case of regulation in which the roles of principal (regulator or designer of contract mechanisms) and buyer are combined; The UK Office of Fair Trading. Assessing the impact of public sector procurement on competition. Volume 2 – case studies (OFT742b). September 2004.

[25] The Commission published this definition on DG Competition’s web-site at: http://ec.europa.eu/comm/competition/general_info/u_en.html#t62

[26] Höfner and Elser v. Macrotron GmbH [1991] ECR I-1979 (C-41/90).

[27] See AG Jacobs, Albany International BV (1999).

[28] A dominant influence of public authorities is in particular presumed when they: a) hold the major part of the undertaking’s subscribed capital, b) control the majority of the votes attached to shares issued by the undertaking or c) are in a position to appoint more than half of the members of the undertaking’s administrative, managerial or supervisory body.

[29] Judgment in EasyPay and Finance Engineering, C-185/14, EU:C:2015:716.

[30] See Sanchez-Graells, Albert and Herrera Anchustegui, Ignacio, Revisiting the Concept of Undertaking from a Public Procurement Law Perspective – A Discussion on EasyPay and Finance Engineering (November 26, 2015). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2695742

[31] Judgment in FENIN v Commission, C-205/03 P, EU:C:2006:453; Judgment in Selex Sistemi Integrati v Commission, C-113/07 P, EU:C:2009:191

[32] See Stadt Halle (C-26/03)

[33] Arriva the Shires Ltd v London Luton Airport Operations Ltd [2014] EWHC 64 (Ch)

[34] Sue Arrowsmith. Brexit Whitepaper: The implications of Brexit for the law on public and utilities procurement. Achilles Briefing paper 2016. https://www.achilles.com/images/locale/en-EN/buyer/pdf/UK/sue-arrowsmith-brexit-whitepaper.pdf