In discussing the mutually reinforcing role of authoritarianism and ‘corrosive capital’, Tena Prelec argues that it is not enough to attract foreign investments to stimulate economic growth that will benefit the whole population; it is essential to guarantee the right environment for them to create real value.

For people studying, investigating and living corruption in the Western Balkans, the most frustrating aspect is its resilience. In spite of the great work done by investigative journalists and civil society in the region – and much of it is of top-notch quality, as the numerous international awards testify – it seems that nothing ever really changes at the top.

Look at Montenegro: its most recognisable political figure has been the very same for the past thirty years. The situation is not much different in neighbouring Serbia, whose president (before that, prime minister) forged his career as Slobodan Milošević’s Information Minister in the 1990s and then warmonger Vojislav Šešelj’s right-hand man – before rebranding his former mentor, and his own ex-party, as political opponents. North Macedonia has experienced some change in recent years (name included), but the EU’s recent failure to reward its efforts by opening EU accession talks puts a question mark against its future prospects.

Political elites in the Balkans have perfected a system of patronage and clientelism that facilitates their survival and perpetuation from one electoral cycle to the other. This is a composite picture that includes a well-oiled game to ensure dominance at elections, the abuse of state resources through politicised public procurement, a nepotistic hiring process, and several other angles. Path dependency plays a role: in the Balkans, the pitfalls of post-communist transition have been amplified by armed conflict and international sanctions, as brilliantly illustrated by Slobodan Georgijev’s account in this blog series. But the methodologies of state capture have also become more subtle and sophisticated than in the 1990s. Conflict is no longer raging on the streets, brazen embezzlement of customs money is no longer allowed – and yet, most of the region is experiencing a democratic involution towards autocratic practices.

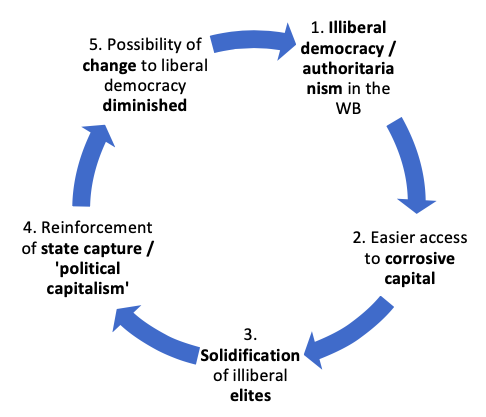

One of these more recent strategies is the use of non-transparent foreign investments to embolden sitting elites, while further walling off the wider public. As I argue in a forthcoming article for the Journal of Regional Security, the return to authoritarian tendencies in the region, especially marked in the 2010s, has facilitated access for a type of investment – equity or loans – that exploits governance weaknesses and exacerbates them: a phenomenon termed “corrosive capital”. Local actors in positions of power are co-opted, ending up working in the interests of foreign investors as well as their own pockets while damaging the state coffers. This further undermines citizens’ belief in the possibility of democratisation, as reflected in the increasing numbers leaving the Western Balkans, and this brain drain reinforces the dominance of the incumbent political and economic elites. Additionally, the lack of a clear European perspective adds to the disillusionment and helps, unwittingly, to reinforce a ‘vicious circle’.

Figure 1. The ‘vicious circle’ of competitive authoritarianism in the Western Balkans, as facilitated by the presence of corrosive capital

From: Prelec, T. (forthcoming), “Going beyond the ‘malign influence of foreign actors’ paradigm: The uneasy relationship between foreign investment and illiberalism in the Western Balkans”, Journal of Regional Security (foreseen publication: mid 2020).

Political cultures could be significant in understanding this phenomenon. Will Bartlett and I have argued that, the more a country’s political and business system allows for a top-down, non-transparent approach in the way its political leadership controls the state finances (for recipient countries) and the investments abroad (for investor countries), the more scope there is for such investments to raise red flags for corruption. Investments carried out behind closed doors by investors operating within a ‘sultanistic’ political culture (that is, one in which public and private resources are heavily blurred) heighten the risk of corrosive capital. This political culture ‘chimes’ with the top-down political-economic style present in several countries of the Western Balkans, many of which have experienced a retreat towards authoritarianism.

While this synergy of autocratic styles of leadership is usually (and, to a certain extent, not without reason) associated with non-Western countries’ malign influence in the region, corrosive capital does not necessarily map neatly on to non-Western vs Western investors. The presence of corrosive capital in the Balkans is as much a Western problem as a non-Western problem, as its facilitators (if not its actors) most often reside in the ‘global North’: the role of Western centres as enablers of non-transparent practices and transactions, including money laundering and reputation laundering, cannot be underestimated. This underlines how corrosive capital has the possibility to prosper, first and foremost, because the rule of law in the Western Balkan countries is extremely weak: the foreign influence can be malign only insofar as the inadequate rule of law provisions of the recipient countries make it so.

It is not enough to attract any old ‘foreign investments’. Investment only stimulates economic growth that benefits the whole population if the right environment exists to create real value. That is why the use of the phrase malign influence to address only non-Western actors in the Balkans is misguided. In other words: it is the situation on the ground, not the origin of the ‘foreign actor’, that really counts in guaranteeing the transparency and utility of foreign investments.

In designing a way forward in their engagement with the region, the EU and the US should be wary of engaging in the same game used by Russian, Chinese, Emirati or other non-Western investors. Rather than pursue informal practices that risk encouraging rent-seeking behaviour, they should provide alternatives and think about a renewed engagement with the Balkans that promises to be truly transformative.

The US special representative for the Balkans, Matt Palmer, has recently encouraged increased US business engagement: this is wholly positive, and should be accompanied by a call for Western companies to apply the same standards abroad that they apply at home – operating within the rule of law and thus acting as role models. Furthermore, a new approach to EU enlargement that prioritises strengthening the rule of law is desperately needed. Such a combination of integrity in practice and renewed conditionality could stimulate good governance, and start to turn the vicious circle into a virtuous one.

This is the sixth blog in a series hosted in the run-up to the event New Actors and Strategies for Fighting and Investigating Corruption in the Western Balkans at the Harriman Institute, Columbia University (7-8 November 2019).

Leave a Reply