By Khalifah Alfadhli.

Every year on June 20th (World Refugee Day), UNHCR updates their report on “global trends of forced displacement”. This shows how, in one year (2014/2015), five million people lost their homes and joined the diaspora nation that reached 65 million for the first time in modern history. Although the refugees crisis has had extensive media attention since 2014 (more than two years since the onset of the war in Syria), the mainstream media still propagate misconceptions about the refugees as either mainly in refugee camps in developing countries or as asylum seekers in Western countries. However, in reality, most refugees live in urban settings in developing countries (top 10 refugee hosts) where they are expected to stay for an average of 25 years, while developed countries are hosting less than 1% of the forced displaced people.

In this blogpost, I will try to shed light on the challenges of the exile environment and how social support available in the refugees’ community helps them to face such challenges, with hope that such understanding of these support mechanisms will lead to better policies and interventions.

Syrian students in Jordan, one of them wearing a UNICEF bag with donor’s flag (photo by the author).

Since 2011, the Syrian war has been a major contributor to the global forced displacement crises, with more than 5 million refugees and 6.5 million internally displaced people. The war is far from over but everybody seems to treat the refugee crises on a temporary basis! Refugees left their homes in a rush (in many cases walking) with hope to return within a few months; many relief programmes are designed for emergency response that succeeds in saving lives but fail in providing livelihood, and the neighbouring host countries (most of them are not part of the (1951 Refugees Convention) do not even consider integrating millions of refugees.

Refugees lose a sense of normal life as they live in a suspended situation where neither returning home nor starting a new life in exile is an option. They receive as little aid as $14/month and rarely find job opportunities, constantly moving from one apartment to another or sharing it with other families to save on rent, while some schools open their doors to refugee children after the regular hours, after the local children finish their school day.

This stagnated situation is not surprising considering the huge pressure on the fragile infrastructure of the hosting countries and the severely underfunded refugee response pledges (less than 10% in Lebanon), which highlights the need for a fresh approach to stressors facing refugees in exile and support resources available for them.

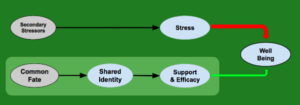

The bad and the good

In an ethnographic study we conducted among a Syrian refugee community in a Jordanian city by the Syrian borders, we were able to identify a spectrum of secondary stressors (i.e., stressors arising from exile, not directly from war). We found refugees to suffer from financial stressors (e.g., loss of income and life expenses), social stressors (e.g., separation from relatives & discrimination) in addition to environmental stressors (e.g., instability and legal issues). Studies have shown that daily stressors have a direct negative effect on mental health of refugees of war, in addition to increasing the chance of psychological problems (e.g., PTSD and depression) among individuals exposed to war trauma. However, the picture is not all grim as the literature about refugees of war in developing countries also shows that the refugees have an innate system of social support to face such challenges which might help in protecting them from the negative effect on their wellbeing. From observations and interviews with Syrian refugees in Jordan, we found many examples of support (on collective and personal levels) in the refugee community, most of which were based on a sense of membership in the ‘refugee’ group. This finding was in line with a rich literature of the role of emergent shared social identity in facilitating social support among people affected by mass emergencies and disasters.

“I do not discriminate between any Syrian refugees regardless of where they came from, Homs or Aleppo or Daraa, we all Syrians… We have same problems, same worries, we open our hearts to each other […] I noticed that my circle of relations has expanded a lot comparing to what it used to be in Syria, as now I have relations with all of Syrian society spectrum (intellectuals, teachers, doctors… etc.). My relations used to be restricted within my region [of origin], but now.. in one place, I would be with people from Homs, Aleppo and Damascus … people I wouldn’t meet back in Syria”

(Syrian Refugee)

A closer look

In a recent survey we conducted among Syrian refugees in Jordan, we found that shared social identity plays a similar role in the support mechanism found among people affected by disasters, where a shared social identity appears to stem from a sense of common fate and leads to social support (practical, emotional and collective) in addition to a sense of collective efficacy. In addition to confirm the existence of shared social identity-based support mechanism among refugees of conflict, we found a positive effect of such mechanism on the wellbeing of the refugees, that appears to – relatively – counter the negative effect of secondary stressors.

These results are preliminary, and further analysis is continuing.

Leave a Reply