By Dermot Barr

In the recent violence in Northern Ireland, children as young as 12 have thrown petrol bombs, families have been forced out of their homes, and undercover British special forces have reportedly been deployed. In this blogpost I will focus on the role that toxic leadership has played in the violence that spread through Northern Ireland in the past month. I will use the terms PUL and CNR as shorthand. However, it is important to recognize that the Protestant/Unionist/Loyalist (PUL) and Catholic/Nationalist/Republican (CNR) labels simplify complex and diverse identities. Most people in Northern Ireland have these identities imposed upon them from birth rather than coming to them through reason. Furthermore, they obscure the central role that economic inequalities play. They are a problematic, but necessary, shorthand for understanding Northern Ireland.

The core of the argument is that a desire to reassert the British PUL identity in Northern Ireland led the DUP to facilitate a hard Brexit. In doing so, they dismissed the potential for violence, and ignored economic realities and decades of unionist betrayal by successive British Governments. Brexit revived the constitutional question in Northern Ireland and therefore increased salience of conflictual PUL and CNR identities. The British government initially denied a border existed, while the DUP claimed Brexit would facilitate a ‘best of both worlds’ position for Northern Ireland. However, empty supermarket shelves, delayed and cancelled deliveries, and most importantly drug seizures soon clarified the border did exist. This also clarified how the DUP facilitation of a hard Brexit damaged the very union they claimed to defend. This failure of leadership strengthened more extreme elements that legitimise political violence. A betrayed PUL identity narrative has since been marshalled by toxic identity entrepreneurs providing expectations of support for violent collective action.

The most recent violence began in Derry on 29th March as police prevented a Loyalist crowd armed with iron bars from entering a mainly nationalist housing estate. Police intervention to prevent sectarian violence led to the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) becoming the main targets of Loyalist violence. Over the following days violence spread to other Loyalist housing estates in Derry, then to other Loyalist areas of Northern Ireland. Some of the most serious violence was seen in Belfast where violent Loyalist protest moved to interface areas (where PUL and CNR communities live in very close proximity) sparking sectarian conflict. The initiation and spread of collective violence in terms of location and target requires explanation. While there are wider factors at play Brexit is at the heart of recent violence.

On the road to Brexit

A slow-motion car crash has unfolded over the past five years in the UK. During the Brexit referendum repeated warnings from former British Prime Ministers, Irish Taoiseach’s a former US president, British Politicians, former Chief Constable of the PSNI, Sinn Fein and more, that Brexit was a threat to peace in Northern Ireland (NI) were dismissed by DUP politicians as ‘project fear’, derided as scaremongering by the then Northern Ireland Secretary Theresa Villiers, and was largely ignored in the referendum campaign in Britain. After an unexpected Leave win, Northern Ireland became the central issue in the negotiations. Those previously warning of the threat to peace were soon joined by others such as the Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Stephen Pound, MI5 and perhaps most importantly Joe Biden.

Warnings of the threat to peace largely centred on the potential hardening of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic. However, David Cameron warned as early as 2016 that a border between NI and Great Britain (GB) was a distinct possibility. Indeed, the Northern Ireland Affairs Committee noted in May 2016 that

‘The UUP told us they had been told by the Government that it did not envisage policing the border with the Republic and that the Government’s preferred solution would be to put in place a more robust system of checks at relevant ports and airports on the mainland.’

Despite this possibility the DUP campaigned for a Leave vote in the referendum, arguably simply to assert their British identity. Dismissing the potential of an Irish Sea Border and campaigning to leave was the first of many bad moves by a toxic leadership which has brought the very violence Arlene Foster dismissed back to the streets of Northern Ireland since the end of March.

Brexit focused existing perceived injustices

Almost five years after the Brexit referendum, on the 26th March 2021, former DUP First Minister Peter Robinson wrote an ominous article warning of the potential of violence. He reported feelings of injustice and alienation within unionism:

PUL communities have experienced status loss in recent years as some of their former privileges in have been challenged. The Parades Commission placed restrictions on Orange Order and Apprentice Boys parades. Within CNR communities these parades were viewed as symbolic of PUL supremacy. In 2012, a decision was made to fly the Union Jack over Belfast City Hall on designated days rather than every day. This brought Northern Ireland into line with the rest of Britain but was viewed as an attack on PUL identities and resulted in a series of riots in the following months. Further moves to bring abortion laws, equal marriage and language rights into alignment with elsewhere in Britain have been opposed by the DUP. Despite making Northern Ireland more like the rest of the United Kingdom, these moves have been perceived as attacks on PUL communities. The toxic use of rhetoric can insure a loss of privilege can feel like oppression. There are heavily deprived PUL communities, but claims that PUL communities are more deprived than CNR communities are incorrect. However, as Peter Robinson pointed out perceptions of injustice ‘do not need to be right’ to motivate action.

Brexit has brought these perceived injustices to a head. The protocol has brought about an economic border between Northern Ireland and Britain. This betrayal of PUL communities by the British government after repeatedly promising not to place a border in the Irish Sea was a harmful blow to PUL communities’ sense of Britishness. Furthermore, the vote needed to pass the protocol is a majoritarian vote rather than requiring cross community support. The British government claim Brexit is an international treaty, not a devolved matter, and as such does not require cross community consent. While this may technically be true, it adds to a perception of injustice within PUL communities. Brexit has demonstrated the political vacuum in PUL leadership who ostensibly did not see the threat to peace. This vacuum arguably added to perceptions that politics did not work for PUL communities, legitimising calls for collective action.

The rhetoric of violence

There is a danger of overstating the extent of recent violence in Northern Ireland. The vast majority of Northern Ireland is not burning. The vast majority of people have no desire to see violence. However, one of the reasons this latest period of rioting is dangerous is that the LCC, an umbrella group for Loyalist paramilitaries, has renounced their support for the Good Friday Peace Agreement and signalled a willingness to use violence. A LCC spokesman warned ‘If Loyalists have to physically fight then so be it’.

Without competent and responsible leadership the potential for violent collective action from one community directed towards the state has the potential to descend into a spiral of sectarian violence between the two communities. The DUP have been accused of legitimising Loyalist terrorist groups by meeting with them earlier this year. However, the language from the DUP has arguably been more incendiary than the LCC. On the 28th February 2021 DUP MP Sammy Wilson called for guerrilla warfare in relation to opposing the protocol: “We will fight guerrilla warfare against this, until the big battle opportunity comes,”

Sammy went on to defend these comments but claimed he was speaking metaphorically. The congruence between paramilitary violence and DUP language arguably creates an expectation of support for violent collective action within Loyalist communities.

From rhetoric to reality

It is worth briefly reviewing the time line of how violence unfolded. The initial violence began in Derry on the 29th March and was sustained till at least 1st April. The move from the initial sectarian spark for political violence in Derry towards a more consistent focus on attacks on the PSNI in other Loyalist areas of Northern Ireland coincided with a decision by the Public Prosecution Service not to prosecute members of Sinn Fein for attending a large funeral of a former IRA member in breach of covid regulations last year. Arlene Foster called for the resignation of the of the Chief Constable on the 31st March as she believed the PPS decision was indicative of an unequal approach to policing that favoured Sinn Fein. Further anti-police violence began in Sandy Row, a Loyalist area of Belfast, on the 2nd April, spreading to Newton Abbey and Carrickfergus on the 3rd and 4th April; more violence was seen in Derry on the 5th of April; and masked Loyalist bands paraded in Portadown, Ballymena and Market Hill in a show of strength. Loyalist violence against the police continued until the death of Prince Philip when it was considered that further violence would be disrespectful. The violence was largely directed at the police. In a familiar pattern, burning barricades and hijacked and burnt out cars were used to attract the police who were then attacked with bricks petrol bombs and fireworks.

It is possible that this violence would have occurred without the DUP calling for the Chief Constables resignation. However, this call and the assessment of two-tier policing is likely to have created perceptions of widely shared grievances and increased expectations for support for collective action against the police. These perceptions and expectations are key to empowering people to engage in violent collective action.

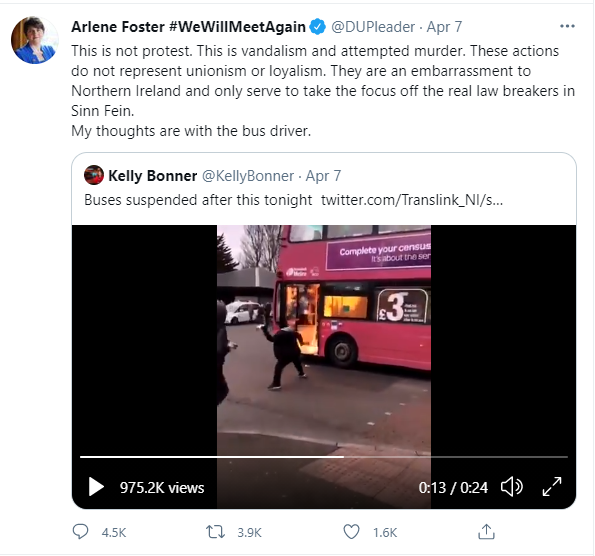

It must be said that Arlene Foster did call for calm and an end to the violence. However, Arlene Foster could be accused of speaking out of both sides of her mouth. Her use of incendiary language continued. On the 7th April a bus was hijacked and petrol bombed in Belfast. Arlene Foster’s tweet in response condemned the violence but argued that it only served to the take the focus of the ‘real law breakers in Sinn Fein’.

A dangerous escalation occurred that night as the focus of Loyalist violence towards the police reverted to violence focused on the CNR community (represented by Sinn Fein). Burning barricades were erected on Lanark Way near a peace line that separates PUL and CNR communities. Rioting then continued between young people with bricks, petrol bombs and fireworks being exchanged across the peace wall.

It must be said that violent protests moved to Lanark Way before the

DUP leader tweeted about losing focus on Sinn Fein and that anti police violence was occurring in some places in Derry before she called for the Chief Constable to resign. She did not direct this violence directly but her language reflected the views of those who were orchestrating violence. She later admitted the 7th April tweet was a clumsy use of language. However, her ‘clumsy’ use of language persists. In recent days the DUP leader has perpetuated the myth of Republicans waging a culture war on Unionists. In the midst of a period of serious political violence this language is at best unhelpful. A less generous interpretation would suggest she is dangerously deflecting attention from the DUP’s strategic incompetence towards sectarian divisions in efforts to demonstrate serious societal difficulties that could lead to Article 16 of the protocol to be invoked. Article 16 of the protocol allows the UK or the EU to act unilaterally to take safeguard measures in case of ‘ serious economic, societal or environmental difficulties’. While sectarian violence is not part of the official DUP plan to invoke Article 16, it is certainly consistent with its stated aim.

Conclusion

I hope to have outlined some observations of how toxic leadership has influenced the spread of violence in Northern Ireland. Brexit increased the salience of shared PUL and CNR identities. The imposition of the Irish Sea border is perceived as an existential threat to the PUL identity. Experiences of the consequences of the border demonstrated a failure of political leadership which legitimised those outside party politics calling for violent collective action. Brexit focused perceptions of shared injustices and arguably informed expectations of support for collective actions primarily against the police but also sectarian violence.

As ever, there are of course wider factors at play. Critics will understandably question the extent to which the young people rioting understand the details and consequences of international trade disputes or pay much attention to politicians. It is notable that rioting occurred during Easter school holidays and involved children. The excitement of engaging in recreational rioting is clear but so are its political overtones. To view rioting solely through PUL CNR divisions sidesteps issues of economic inequality. An excellent piece of writing in the Irish Times illustrates the complex influence intersecting issues of deprivation and the exploitation of children.

I have focused on toxic political leadership; however, there are clearly more practical influences at work too, such as the disruption to the importation of drugs that the Irish Sea border poses. However, the spread and maintenance of violence points to fundamental identity-based issues. It is impossible to adequately address all factors in a blogpost. I have argued that a DUP desire to maintain its own relevance through differentiating Northern Ireland from the Republic by facilitating a hard Brexit resulted in damaging the very union they claim to protect. They have attempted to deflect from this blunder through toxic rhetoric aimed at the PSNI and Sinn Fein. This toxic leadership has a role to play in explaining the occurrence, spread, and targets of recent rioting.

Leave a Reply