by Harry Lewis

Safety at live music events has become an increasing concern in recent years, spurred by high-profile incidents that have attracted global attention. These incidents have driven calls for more government support and funding to improve crowd safety at live events, without which, experts argue, further incidents are inevitable.

Widely reported crowd disasters underscore the inherent risks of participation in large crowds. The dynamic nature of crowd events make it difficult to establish a hard and fast metric for safe crowd density. However, densities well exceeding the 5 people per square metre maximum recommended in some guidance regularly occur at live music events without causing a safety incident, and without diminishing attendees’ positive experiences. This raises the question: if safety isn’t purely about density, what other factors influence audience experiences of safety at live music events?

Over the past two years, we have been conducting research looking at people’s experiences of participation in crowds at live music events. As part of this, we have explored the factors which influence perceptions of safety. Our research combines insights from 26 interviews with regular attendees and event staff in the UK and USA, ethnographic observations at large-scale events, and survey responses from over 2,000 participants to uncover the factors influencing felt safety at live music events.

Feeling Safe in a Crowd

Research has previously shown the role of the crowd in influencing perceptions of a safe environment. Specifically, work adopting a social identity approach to crowd behaviour highlights how participating in a crowd can foster a sense of shared group identity, which in turn can influence the values and behaviours deemed acceptable within the crowd. These findings have been replicated in the context of live music events. For instance, Morton and Power (2021) demonstrated how shared identity and trust among festival attendees played a crucial role in fostering perceptions of safety when live events re-opened following closures imposed because of the COVID pandemic. Elsewhere, Drury and colleagues (2015) investigated a near disastrous outdoor music event, finding that that social identification within the crowd enhanced feelings of safety by fostering trust and expectations of mutual aid among attendees.

Similarly, across our interviews, we found that other members of the crowd were cited as one of the most important factors in perceptions of safety. Interviewees frequently mentioned that their sense of safety was influenced by the behaviour and perceived identities of those around them. Attendees felt safer when they shared identity with others in the audience—be it based on age, gender, or a shared love for the same genre of music.

Previous research on crowds at religious mass gatherings and mass demonstrations found that sharing identity with others can lead people to feel safe in a crowd, even where levels of density are very high and objectively dangerous. Echoing this, our survey found that participants who felt a stronger sense of identity with others in the crowd were more likely to report standing in a crowded location.

This is not to say that shared identity with other members of the crowd is the only factor influencing perceptions of safety. Many of our interviewees highlighted the role played by atmosphere in promoting feelings of safety: a positive and cohesive crowd mood — often inferred through interactions and responses to the music — can help foster a sense of community and security. Conversely, poorly managed events can lead to frustration and erode this sense of positive atmosphere, increasing feelings of vulnerability, and highlighting the importance of organisational factors in contributing to feelings of safety.

Our survey study provides further evidence of the role of organisational factors: alongside the friendliness of others in the crowd, both the appropriateness of security measures and the presence of staff were found to positively influence participants’ sense of safety. This was echoed in our interviews, where participants frequently emphasised the importance of contextually appropriate security measures. While visible security was reassuring at larger events, it could inhibit a sense of freedom and expression at smaller gigs. Striking the right balance between professionalism and relatability is crucial for staff to positively contribute to the overall event atmosphere.

Just as a common identity within the crowd is important for enhancing safety, so a common identity with staff and organizers is crucial. Of course, staff are not ‘the same’ as the audience, but at another level they can be seen as ‘our staff’ in a superordinate group identity. This inclusive sense of community or ‘family’ is something that successful festivals like Roskilde and Glastonbury promote, and it is key to their identity.

How does one create such a superordinate identity and how does it contribute to safety? Our survey found that the more that audience members felt that staff treated them in fair and supportive way, the more that they felt a sense of community with staff, which in turn predicted trust in staff and listening to them. In short, the more that audience members see staff as ‘part of our group’ the more likely they are to follow any safety instructions from them.

The Crowd as a Safety Resource

Despite the inherent risks associated with participation in dense crowds at live music events, crowds themselves can be an incredibly valuable safety resource. Multiple interviewees gave examples of support they had received in times of need in a crowd, again often tied to a sense of shared identity with others at the event.

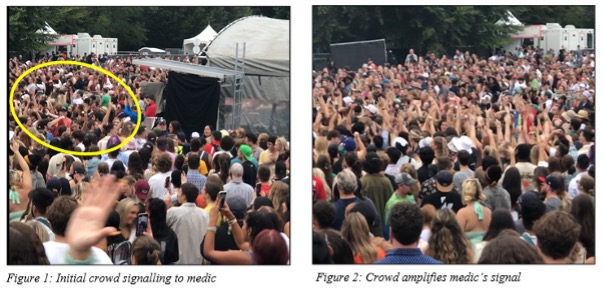

In fact, we observed this capacity of the crowd to act as a safety resource during our ethnographic work at a three-day festival in Atlanta, USA. During a performance, we noticed a medic walking through the crowd to attend to an audience member, with a few attendees in the area appearing to signal to the medic the precise location (see Figure 1, below). Interestingly, once at the scene, the medic appeared to signal towards the front of the stage, both waving and using what looked like a flashlight. This resulted in a large number of attendees in the immediate vicinity joining in the signalling to the front by waving (Figure 2), thereby amplifying the medic’s signal, and ultimately resulting in an acknowledgement from the artist, who proceeded to check with the group in that area:

Artist: “Can we get someone in the middle here? We’ve got someone down. [Asks audience] They’re coming? They’re coming? Oh they’re good, they’re good.”

Figures 1 and 2: Members of the crowd work together to collectively signal for medical assistance

The Artist’s Role in Crowd Safety

The above example points to a further factor in experiences of safety in crowds at live music events – the role of the artist. Artists emerged as significant influencers of crowd behaviour and safety perceptions. Many interviewees highlighted the duty of care artists hold in setting the tone for events, highlighting how artists have the capacity to carefully choreograph crowd interactions and crowd movement, as well as establish general safety norms such as one example where the lead singer of a band requested audience members to wear masks in relation to the COVID pandemic to reduce health risks.

Artists can also undermine safety. Some interviewees described incidents where artists encouraged risky behaviour, such as ignoring venue rules, leading to crowd management challenges. Others described how an artist turning up late led to a feeling of restlessness and aggression within the crowd – something again observed in our ethnographic research, where crowd members waiting for a late artist took to throwing bottles of water into other areas of the crowd.

The power of the artist to shape crowd behaviour, and the limits of that, is further evidenced in our survey study. When participants were asked which factors most influence crowd behaviour, the artist was listed as number 1, above the organisation of the event and even levels of intoxication of other crowd members. This appears to be particularly the case for participants who identify strongly as a fan of the artist – those who identify as fans more strongly are more likely to respond to calls for action which come from the artist, including potentially unsafe behaviours such as jumping up and down, crowd surfing or participating in a ‘wall of death’.

What This Means for Practice

Our findings have several practical implications for event organisers, artists, and staff:

Foster a Positive Crowd Atmosphere: Facilitating a sense of shared identity and mutual respect within the crowd, and between the crowd and staff, can significantly enhance safety perceptions and objective safety. This can be achieved through communication of event values beforehand, fostering inclusive environments, and forms of (fair and supportive) interaction with staff during the event (informative, engaging/ listening, empathizing, respectful).

Consider Pre-Event Organisation: The perception of safety begins long before attendees arrive at the venue. Transparent communication about safety protocols — such as health measures or ticketing procedures — can reassure attendees that organisers take their safety seriously. We know safety and service are linked – both in audience experience and in underlying psychology. So link these procedures to audience experience: ‘this is how we care for each other’.

Leverage the Crowd as a Safety Resource: Crowds can act as a valuable safety resource through their capacity to coordinate actions like signalling for help or maintaining order (collective self-regulation). Event organisers should ensure that staff are trained to recognise and respond to such signals effectively, through knowing group psychology.

Equip Artists with Awareness: Artists should recognise and understand their influence on crowd behaviour and receive guidance on how to set positive behavioural norms. Small actions, such as acknowledging safety concerns or addressing inappropriate behaviour, can make a significant difference. Just as staff need to understand the group psychology underlying audience behaviour and experience, so do artists.

Conclusion

Felt safety at live music events is not solely determined by logistical factors but is deeply intertwined with the behaviour and identities of the crowd, artists, and staff. By fostering shared purpose and trust among all parties involved, event organisers can create environments that not only feel safer but also enhance the overall experience for attendees. As the live music industry continues to evolve, these insights offer valuable guidance for creating safer and more enjoyable events for everyone.

Acknowledgements

The research described in this blogpost was the work of Harry Lewis, John Drury, Hanna Eldarwish, Danielle Evans, Fiona Green, Sanj Choudhury and Lewis Doyle.

Leave a Reply