Written by Oliwia Kaczmara

Spending a week in Indian-administered Kashmir is nowhere near enough time needed to fully appreciate the beauty of the breath-taking mountains and enchanting lakes. Having such little time there in August 2023, what became very apparent to me was the striking around-the-clock surveillance that hits you in the face straight upon arrival. The countless roadblocks and military checkpoints on the way into the Kashmir Valley, do not calm the fear from a 15-hour long drive on winding roads through the pitch-black night, where all you can see is hundred feet tall cliffs on your side, waiting for a deadly boulder to tumble down at you at any moment. The helplessness in the face of nature’s grandiosity, however, is nothing compared to the powerlessness of witnessing human-inflicted suffering that the Indian occupation has forced onto Kashmiris, ever since British India’s 1947 partition.

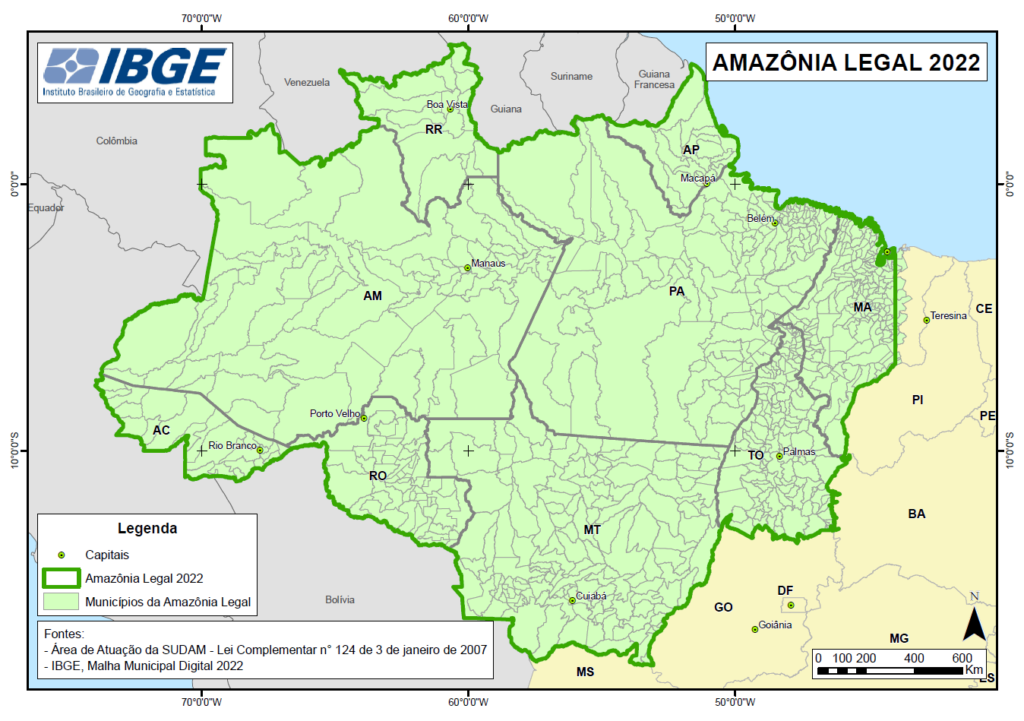

When the once princely state of Kashmir, which refers to the Kashmir Valley that is about 90-miles long, was divided up between India and Pakistan in 1949 after their 2-year war over the region, two-thirds of the territory landed in India’s hands, and one-third in Pakistan’s. The Line of Control (LoC)[1], drawn up by the UN, still remains in place today and it is the Indian two-thirds of the Kashmir region that this blog refers to.

The continuous assertion of land control over Kashmir by the Indian state has been historically characterised by a series of different mechanisms that have all aimed at compromising Kashmiri bodies’ ability of resisting the occupation, whether it be at a physical level, by excessive use of pellet guns (Zia, 2019), or at a psychological level by capitalising on the trauma and PTSD of Kashmiris (Duschinski et al., 2018). However, what I will discuss in this blog is what I consider the ‘new frontier’ of India’s land control – sand extraction – and ecocide as its consequence. Analysing this through the lens of ‘extractivism’ – “a regime based on the capture of value from nature in which production occurs without reproduction” (Ojeda et al., 2022: 2) – brings a new ecological dimension to understanding the conflict, alongside the physical and psychological. Here, the ‘killing’ of the natural environment merely becomes a tool for reproducing the vision of the occupation forces in the Himalayan foothill terrain. Viewing extractivism and ecocide as mechanisms of India’s settler colonialism, highlights the coming together of dreams of control and capitalism, which will continue to devalue Kashmiri lives and land, as long as the occupation lasts (Crook and Short, 2021).

Extractivism and Ecocide in Settler Colonialism

Sand mining is not a widely known form of extractivism such as oil or precious stones, yet it is the single most mined commodity and the most exploited substance after water (UNEP, 2022[2]). If, like me, you haven’t heard about sand mining before, then you may not know that sand is used in production of concrete, and so effectively in every one of our construction or manufacturing processes and is even used as an ingredient in our toothpastes. The amount of daily sand consumption equates to 20kg per person and currently “we are extracting sand more than three times faster than nature can replenish it” (Hall, 2020[3]).

Sand extraction in India has gained significant traction in the past decade due to the country’s construction boom, however it’s important to distinguish between ‘extraction’ and ‘extractivism’, as it is the latter that is destroying the riverbanks of Kashmir in irreversible ways. Junka-Aikio and Cortes-Severino differentiate the two by defining extractivism as “a paradigm of severe exploitation” (2017: 177). Extractivism as a product of capitalism prioritizes monetary gain and monopoly control, benefiting the resource exporters more than the resource rich countries (Ye et al., 2020). It is a relentless process that doesn’t respect natural rhythms of regenerations, leaving behind nothing except ‘negative externalities’ such as disadvantaged local populations and toxic pollution (Ye et al., 2020). It is a process of ecocide in the name of profit.

Environmental degradations caused by military presence is a big issue in conflict zones around the world, most recently for example, Palestinian soil becoming infertile and biohazardous thanks to countless Israeli bombardments. There have been many comparisons made between the situations of Kashmir and Palestine, most notably by Ather Zia (2020) who outlines the main similarities between the two states as following; both countries were under the control of the British Empire in 1947, they both have been portrayed as lawless Islamic terrorist states in the public eye, and the motif of ‘suffering’ is deeply ingrained within both national identities. In both cases, there is a lot to learn about ecocide not only as a byproduct of war, but also how it is used in extractivist regimes as a strategy of occupation.

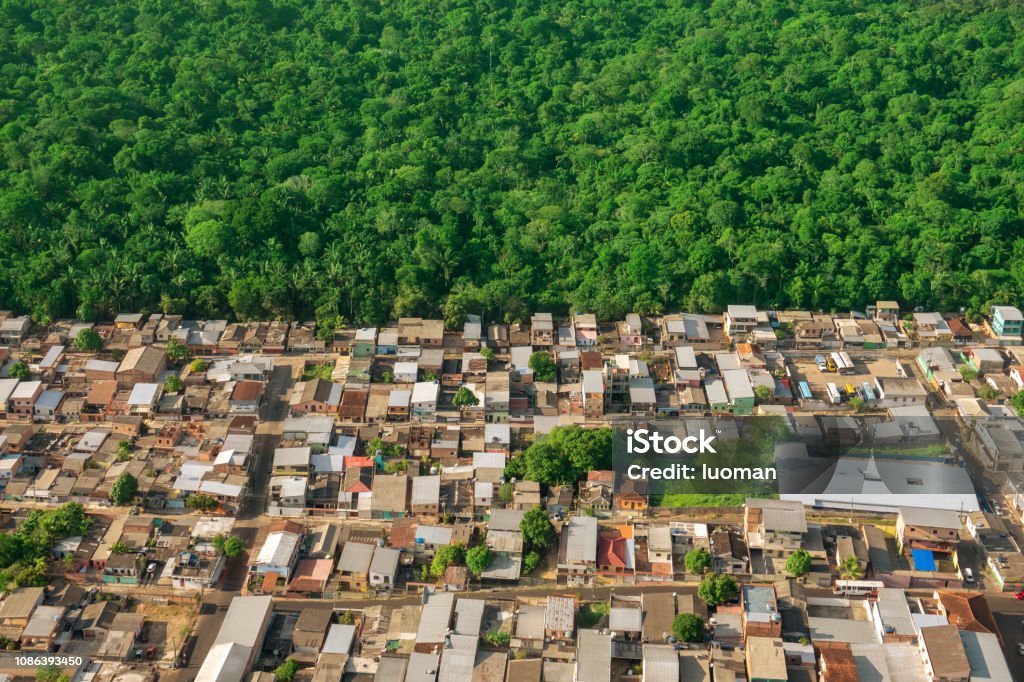

As proposed by Jaber (2019), settler colonialist ideologies aim to erase traces of previous indigenous life which involves the people and their culture, but also their physical and ecological conditions. Jaber (2019) argues in their research that settler ‘spaces’ built upon Zionist ideologies are inherently ecocidal towards Palestinian land. This framework of thought can also be seen in the Hindutva and Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) homogenizing ideologies with regard to Kashmiri land. The creation of a settler exclusive space is simultaneous with ecocide because “the ability to dominate and manipulate an ecology for power benefits, contributes to the settler goal of native elimination” (Jaber, 2019: 142), which in the case of Kashmir is exemplified through the occupational forces deliberately disadvantaging locals from land access and bringing in outsider sand extraction businesses that fulfil the BJP’s goals of ‘development’ for the unified ‘Rising India’.

The environmental impacts of sand mining

In India, the sand extracted in the peripheries doesn’t leave the nation’s borders and is mostly used for the development of the country’s core financial centres, like Delhi and Mumbai, with no trickle-down effect back to the original extraction locations. This is especially evident in the city of Shopian which is surrounded by two rivers – the Rimbiara and the Veshav – of which both have been exploited by heavy machinery since 2019 for their untouched, sandy riverbeds. The intense and endless digging that followed the abrogation of Article 370 which revoked the special autonomous status of Jammu and Kashmir, integrating it fully into India as two separate Union Territories; Jammu & Kashmir and Ladakh, has had severe environmental and social implications that, in Kashmir, are as much to do with the conflict as the profit motive.

Sand mining has enormous and catastrophic effects on the ecosystem, affecting every living organism. From erosion of riverbanks, loss of biodiversity and a threat to livelihoods through disrupted water supplies, food production and fisheries. Most of all, the deep puncturing of the riverbeds from sand digging produces a very high risk of climate-related disasters because there is no longer enough sediment to protect the nearby areas against flooding. In the words of a Shopian local, Mukhtar Ahmed; “Tractor owners, who extracted sand with hands, did not damage the river as much in fifty years as machinery has done in six months”[4].

As per local rules and agreements, extraction can only occur up to three to four feet in depth, however external mining businesses have illegally dug more than 50 feet, causing serious danger of floods for nearby residents. The deep punctures in the waterbed caused by the extraction from heavy machinery have made the damages irreversible and now it is impossible to bring back the original freshwater flow. Disturbing the riverbeds has also severely damaged water canals that supply fresh tap water. Locals have been reportedly receiving a Rs 1,000 water bill every month, despite the fact they have not had a supply of fresh water for months.

The Jammu & Kashmir district is also the primary source of apples in India, providing 80% of all apples in the country[5], and the apple crops destroyed by sand mining or the water-starved soil create financial losses for the local farmers that are disastrous for their livelihoods. A local apple orchard owner, Bashir Ahmad[6], notes that the freshwater quality is so bad that even the fungicide they spray on the trees has now become futile and the crops are beyond saving.

Where local farmers struggle, companies have stepped in to take advantage and many of the new landowners in Kashmir are corporate actors. As reported by Mukhtar Ahmed[7], these groups have been engaging in various acts of bribery in order to keep the locals away from the rivers. The firms, which earn remarkably more than locals, regularly bribe local administrations with Rs. 50,000 so that they receive mining priority. The local miners that do manage to still extract sand with their hands and tractors and earn around Rs. 1,000 daily, are often forced to pay a bribe ten times bigger to the local authorities to transport the manually dug out sand. Knowing how absurd the price difference becomes, many of the locals abandon their hard-earned sand as they simply cannot afford it. Around 10,000 manual sand mining labourers from 10 to 15 villages around Shopian have also been made unfairly redundant by the new big sand mining companies that, according to Abdul Ahmed Dar[8] – a local mining worker – use violence or bribing to kick local workers out of their sites.

The combination of dispossession and income loss, on top of already hard living conditions for all the rest of the residents – no fresh tap water, the possibility of your house being washed away and living in one of the most militarised areas of the world – are not conditions that should be imposed upon a person just because they were born one Himalayan valley away from peace. Not only has then the sand extractivism directly seized basic water supply but also indirectly removed people’s main sources of income and a stable life.

Kashmir in the public eye

The ecocide caused by the sand mining boom and the political factors behind the Indian occupation of Kashmir are not however isolated events, but are deeply intertwined. Since coming into power in 2014, the BJP party’s aims have been mainly pro-big business and winning their voters through propagating their idea of a ‘Rising India’, a reason for the major construction boom around that time. The country has been flooded with ‘development projects’ such as extremely long flyovers and expressways that relieve commuters from having to travel through slum neighbourhoods. As of today, India has 47 expressways that total 3,466 miles in length[9], which is exactly the distance between London and New York in a straight line. Of course, to build all those new development projects and all of these roads, sand is needed, and so more intense sand mining than ever is needed, making the abolition of Article 370 and within it, article 35(A) an ideal gateway into Kashmir’s riverbeds.

Modi’s justification for scrapping almost all of Article 370, was a pretext for integrating Kashmir with the rest of India and not giving it any special treatment so that it can resemble other Indian states. However, to Kashmiris, this decision was a step towards complete annexation of the territory (Zia, 2019: 778) which is precisely what followed. Article 35(A)[10], which is a section of Article 370, pointed out specific domicile laws regarding residency statuses in Kashmir. However, with its demolition and a new law in its place, Indian nationals living outside of Kashmir who meet specific requirements can be granted domicile status, giving them the right to apply for government employment and land in the area. This new law has led to up to 25,000[11] new people being granted residency certificates, explaining the sudden influx of external sand mining businesses.

The abrogation of Article 370 was thus a neoliberal economic policy that allowed for state territorialization to take place. Peluso and Lund (2011) explain ‘territorialization’ as various means of controlling territory and land for a bigger purpose of people and resource control. In short, simply “power relations written on land” (Peluso and Lund, 2011: 673). In the context of Kashmir, the government’s prioritization of access to the territory for mass sand extraction also served the bigger aim of developing a ‘united’ India.

To assert the claim over Kashmiri soil even further, the government chose to auction the first 200 mining areas online in February 2020. Ironically, 4G internet connection has been completely cut off in Kashmir since the abrogation of Article 370 and within the first year, any internet connection was also cut off from access 50 times in total (Zakaria and Baba, 2020). Therefore, Kashmiris became disadvantaged with regards to purchasing their own land whilst anyone outside of Kashmir had a strategic, better advantage. Assigning Kashmir’s territories to new owners through systems that disadvantaged Kashmiri locals from equal land access also simultaneously dispossessed them from the land that has sustained them for many centuries and has effectively turned them into ‘illegal’ ‘poachers’ in the eye of the state.

The framing of the Kashmiri people as dangerous and undeveloped citizens in the public eye, also legitimises sand mining’s exploitations. Prior to India’s security concern of the Kashmiri insurgency, Kashmir has been highly romanticized and portrayed as a place of escapism, and often a perfect location for the setting of many famous Bollywood movies[12]. This however changed from the 1990s onwards, when Kashmiris intensified their demands for independence and consequently their portrayal became ‘the other’, and potential terrorists.

As highlighted by Nitasha Kaul (2018), the exoticisation of the Kashmir territory also has a gendered aspect to it that drives the military goals of India’s possession of the territory. As Kaul explains, the feminisation of Kashmir is crucial for “the ‘strong’ hegemonically masculinist neoliberal state of India” (2018: 119), as it turns Kashmir’s ownership and governance into a vital component of Indian nationalism’s self-image.

These series of environmental, social, economic and political changes have all worked against Kashmiri people and in favour of big corporations and government control. Apple farmers and manual sand miners have lost their incomes, their families have lost a stable life, freshwater and internet access have become limited and the riverbeds irreversibly damaged, all in the name of ‘development’ fuelled by extractivism. These policies not only chip away at the viability of local lives, but also attempt to rob people of the hope of a peaceful future.

The paths to a solution

It is clear from the example of Kashmir that local sand extraction is not an issue itself, as people have been doing it harmlessly for decades. However, when enrolled in an extractivist regime, with the objective of capital accumulation and state control, irreversible damage is caused with no regard for the environment.

From a demand side, moving our societies and communities towards a circular economy for concrete, and creating a more rigorous recycling infrastructure would decrease the need for new sand extractivism. Studies have found that using recycled glass and plastic in concrete production instead of sand, would reduce CO2 emissions by 18% and we could save 820 million tonnes of sand per year (Hall, 2020[13]). To cut down on extractivism however, we must challenge the very logic of capitalism and colonialism.

As this blog has shown, in Kashmir, extractivism and ecocide are key mechanisms of settler colonialism that will continue to cheapen Kashmiri lives and land (Crook and Short, 2021). Therefore, extractivism in Kashmir will continue for as long as the occupation continues, and the root of the solution certainly needs to be about the liberation of Kashmiris at its forefront, and not just about better ways of mining.

Bibliography

Crook, M. and Short, D. (2021). Developmentalism and the genocide–ecocide nexus. Journal of Genocide Research, 23(2), pp.162-188.

Duschinski, H., Bhan, M., Zia, A. and Mahmood, C. (eds), (2018). Resisting occupation in Kashmir. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Falk, R.A. (1973). Environmental warfare and ecocide—facts, appraisal, and proposals. Bulletin of peace proposals, 4(1), pp.80-96.

Hall, M. (2020). 6 things you need to know about sand mining. Mining Technology. Available at: https://www.mining-technology.com/features/six-things-sand-mining/?cf-view [Accessed 11 May 2024].

Harvey, D. (2017). The ‘new’ imperialism: accumulation by dispossession. In Karl Marx (pp. 213-237). Routledge.

Higgins, P., Short, D. and South, N. (2013). Protecting the planet: a proposal for a law of ecocide. Crime, Law and Social Change, 59, pp.251-266.

Jaber, D.A. (2019). Settler colonialism and ecocide: case study of Al-Khader, Palestine. Settler Colonial Studies, 9(1), pp.135-154.

Junka-Aikio, L. and Cortes-Severino, C. (2017). Cultural studies of extraction. Cultural studies, 31(2-3), pp.175-184.

Kaul, N. (2017). Rise of the political right in India: Hindutva-development mix, Modi myth, and dualities. Journal of Labor and Society, 20(4), pp.523-548.

Mar, T.B. and Edmonds, P. (2010). Introduction: Making space in settler colonies. In Making settler colonial space: Perspectives on race, place and identity (pp. 1-24). London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Peluso, N.L. and Lund, C. (2011). New frontiers of land control: Introduction. Journal of peasant studies, 38(4), pp.667-681.

UNEP (2022). Sand and sustainability: 10 strategic recommendations to avert a crisis. GRID-Geneva,

United Nations Environment Programme, Geneva, Switzerland

Ye, J., Van Der Ploeg, J.D., Schneider, S. and Shanin, T. (2020). The incursions of extractivism: moving from dispersed places to global capitalism. The Journal of Peasant Studies, 47(1), pp.155-183.

Zakaria, A. and Baba, W. (2020). The false promise of normalcy and development in Kashmir. Al Jazeera. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/8/5/the-false-promise-of-normalcy-and-development-in-kashmir [Accessed 11 May 2024].

Zia, A. (2019). Blinding Kashmiris: The right to maim and the Indian military occupation in Kashmir. Interventions, 21(6), pp.773-786.

Zia, A. (2020). “Their wounds are our wounds”: a case for affective solidarity between Palestine and Kashmir. Identities, 27(3), pp.357-375.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Line_of_Control

[2] https://www.unep.org/resources/report/sand-and-sustainability-10-strategic-recommendations-avert-crisis

[3] https://www.mining-technology.com/features/six-things-sand-mining/?cf-view

[4] https://youtu.be/FeFWBSu1PKM?si=JbXZggTAXvx4K6Jt&t=76

[5] https://kashmirobserver.net/2021/03/22/apple-economy-in-jammu-kashmir-changing-paradigm/

[6] https://youtu.be/FeFWBSu1PKM?si=A1Qm1MySTZVG8kWT&t=256

[7] https://youtu.be/FeFWBSu1PKM?si=PUOVx7PUsvJucW7-&t=99

[8] https://youtu.be/FeFWBSu1PKM?si=A680dYhDv0Uj0jLQ&t=124

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Expressways_of_India

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Article_35A_of_the_Constitution_of_India

[11] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/6/28/kashmir-muslims-fear-demographic-shift-as-thousands-get-residency

[12] https://thediplomat.com/2019/08/bollywood-and-indias-evolving-representation-of-kashmir/

[13] https://www.mining-technology.com/features/six-things-sand-mining/?cf-view