by Ceri Oeppen, Senior Lecturer in Human Geography, Sussex Centre for Migration Research

*The views in the following article are the personal views of the author and are not an official position of the School.*

In today’s Queen’s Speech to Parliament, the UK Government lays out their agenda for the coming year. One of those agenda items is their ‘New Plan for Immigration’.

The speech will likely make much of the Plan’s stated aims to ‘promote legal pathways to protection’ and ‘protect UK borders’, but in reality, the Plan is full of discriminatory proposals that are highly unethical, and, I predict, will be subject to legal challenge.

The Government’s ‘New Plan for Immigration Policy Statement’ sets out their plans, and was subject to a public consultation, which closed just three working days ago*. We, at the at the Sussex Centre for Migration Research (SCMR), responded to this consultation in detail, in discussion with community partner Sanctuary on Sea, who also responded, because we are so concerned at the New Plan’s content.

We are not the only ones worried. The UN Refugee Agency wrote a 35-page document covering their observations (the summary is here), concluding that “many aspects of the Plan do not respect fundamental principles of refugee law” (pg. 34). Countless other refugee, migrant and asylum seeker rights groups, and migration studies academics have also expressed distress at the New Plan’s content.

So, what are we so worried about?

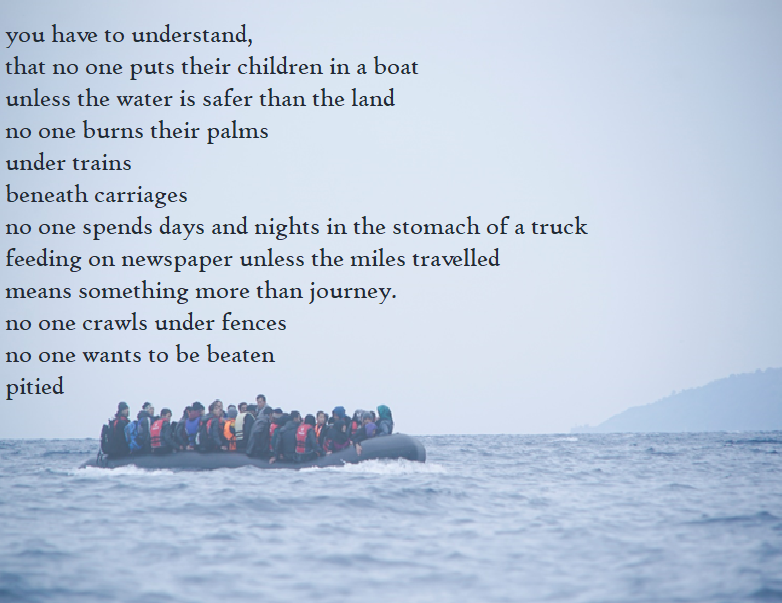

Whilst the Plan proposes a number of changes to British immigration policy, most worryingly, it shows the government aims to penalise those refugees who arrive in the UK through irregular means (e.g. with smugglers) rather than recognising that, for many people from conflict-torn countries, this is the only possible way to enter the UK. This is unethical, and in contravention of a good faith interpretation of the UN’s Refugee Convention (signed and ratified by the UK in 1951), making it potentially illegal too.

According to the Refugee Convention, asylum seekers should not be penalised based on their manner of arrival, and those recognised as refugees should receive the same rights and support as citizens during their stay.

The UK Government’s New Plan for Immigration proposes lesser support, rights and protection to those who arrive in the UK via irregular means (i.e. smuggled into the UK), versus those who arrive through formal resettlement or family reunification.

This will create a two-tier system, reifying the image of the ‘good refugee’ (one of the tiny minority who arrive through resettlement – 5,610 in 2019) vs. the ‘bad’ (those who through lack of other options arrive in the UK via the use of people smugglers).

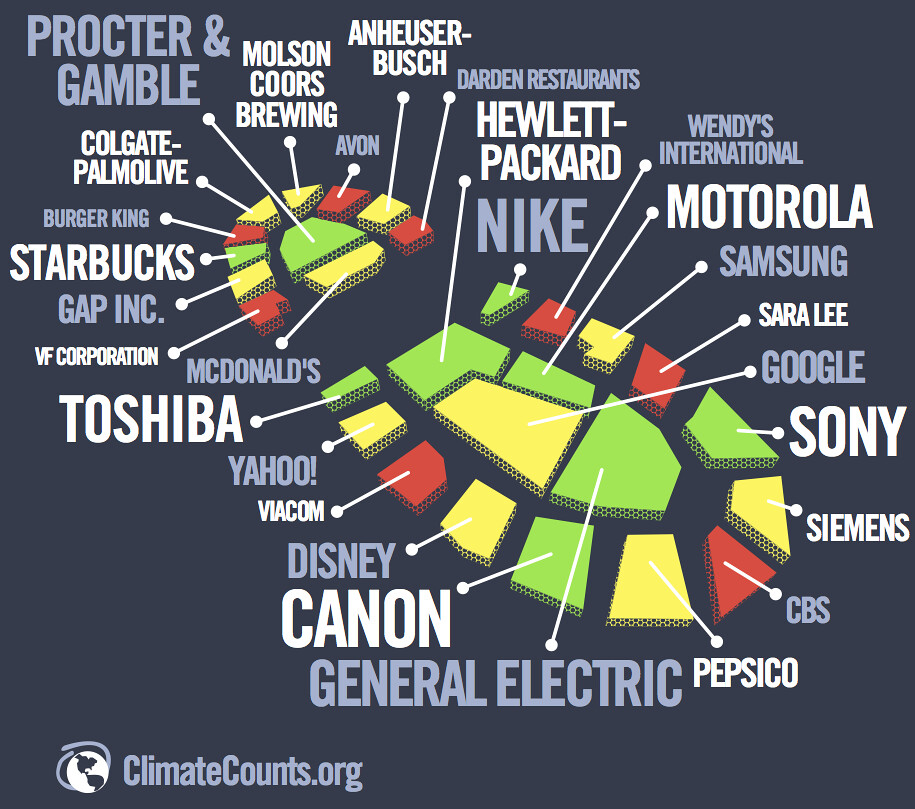

Whilst the New Plan claims that they aim to “break the business model of the people smugglers”, it is clear from countless first person, academic and journalist accounts that it precisely the existence of border controls, border policing and the lack of safe, regularised, routes that drives the business model of people smugglers. They are the only option for all but the 0.5% of global refugees who are resettled from refugee settlements in lower/middle-income countries to higher-income countries.

If you live in a country like Afghanistan, Syria or Somalia, or you’re ‘stranded’ in a detention centre in Libya or a refugee camp in Greece, you cannot just apply for asylum in the UK, even if you speak English and have family or others to support you in the UK. You can only apply for asylum on arrival in the UK, and as you will not be granted an entry visa (precisely because you come from Afghanistan, Eritrea, Syria etc), your only option is to arrive through irregular means. The more aggressively borders are enforced, the more likely you are to need the help of smugglers to enter the UK in order to exercise your right to claim asylum, despite the risks both financially and in terms of physical safety. The New Plan for Immigration proposes to penalise those who arrive in this manner, even if their asylum claim is accepted and their status determined as a refugee, by providing only temporary protection, and reduced access to other rights and support. This is in contravention of the Refugee Convention.

There are other issues with the New Plan: it does nothing to address the issues we see faced by those in the asylum system (destitution, a culture of disbelief, hostile environment, unsafe/unsanitary accommodation, serious damage to health and mental well-being), makes ample use of xenophobic divisive language, and conflates terms (asylum seeker, refugee, illegal immigrant, foreign national offender). It also states aims to amend previous immigration acts, in order to enable the possibility of future ‘offshore’ asylum processing and accommodation. Much like the extensively-criticised Sewell Report on race, the policy statement about the New Plan makes virtually no use of academic, or other independent research evidence about the impacts and feasibility of immigration policy, and fails to build on best practice advice from international bodies like the UN.

The vast majority of refugees remain in their country and region of origin. If the UK government wants to live up to its aspirational image of ‘Global Britain’, the least it can do is support and protect those people who do arrive in the UK and claim asylum, no matter the manner of their arrival, and do so in line with the international standards of protection for refugees that the UK helped draft in the 1951 Refugee Convention.

*The consultation process itself has also been widely criticised, not least for closing just days before the Queen’s Speech, but also for not allowing enough response time, for pushing respondents to an unwieldy, unfriendly, internet platform, for asking (mis)leading questions and not enabling responses from those most affected (i.e. migrants, asylum seekers and refugees).