writes Leverhulme Fellow Alice Corble

*The views in the following article are the personal views of the author and are not an official position of the School.*

This blog post summaries and reflects on collaborative work between three members of University of Sussex Library staff who have different roles in different but intersecting library teams: Danny Millum, Collection Development Librarian in the Collections team; Tim Graves, Systems Librarian in the Digital Discovery team; and myself, Alice Corble, Teaching and Learning Supervisor and RLUK-AHRC Research Fellow in the Student Experience team[1].

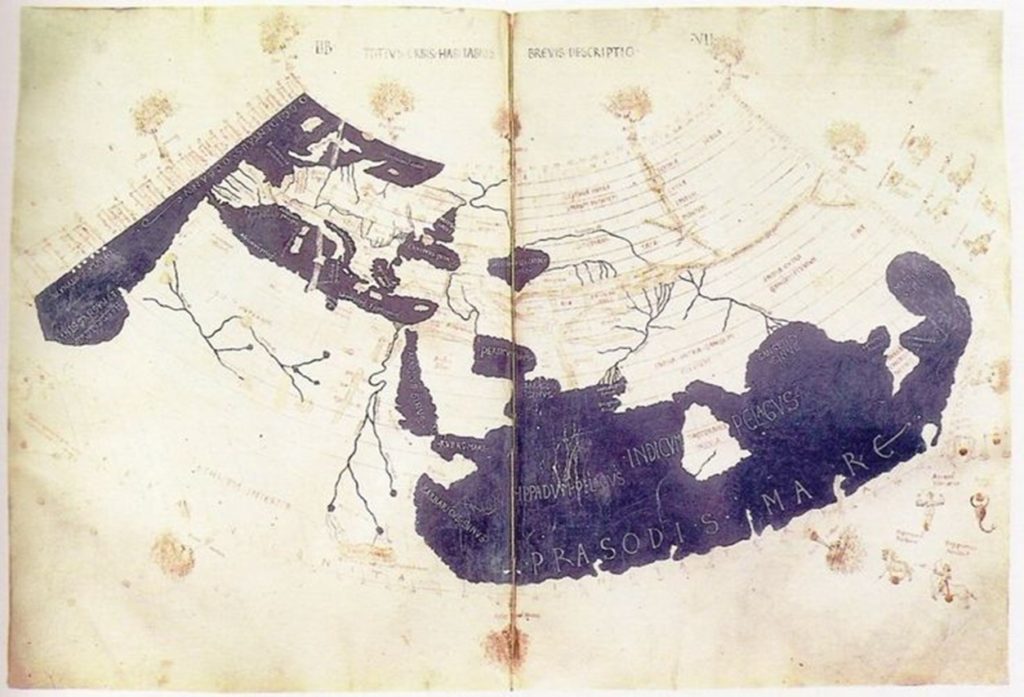

What joined us together through this collaboration is a shared enthusiasm for improving and diversifying discoverability and usage of library collections via innovative approaches to mapping, visualizing and analysing collections data. The British Library for Development Studies (BLDS) Legacy Collection is the perfect vehicle for these converging interests, with particular relevance for my research focus on postcolonial landscapes of library learning and collection development. We came together in a pilot project to explore innovative ways of digitally mapping BLDS catalogue metadata, in order to experiment with alternative catalogue discovery tools that would inform and expand user experience, as well as to highlight the geopolitical distinctiveness of this unique collection.

Being explorers ourselves in a new university, explorers with ample maps of other universities but with none of our own, we wanted to make our students into explorers also, to encourage them to find relations between subjects where we did not see them ourselves, and to dispute some of our own conceptions. Given the huge changes which are taking place both in the formulation of new knowledge and in the world of action where the knowledge is being applied, we did not want to be confined to our own original territory even though the boundaries within it were being knocked down. We recognized that we would also have to move into outer space. The main interest was in planning not for present change but for future change. There are likely to be immense rearrangements in the map of learning during the next fifty years…

(Asa Briggs, 196

The University of Sussex (UoS) Library houses the BLDS Legacy Collection via a partnership with the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). This vast and diverse collection charts global knowledge landscapes of international development politics, policies, ideas, movements, and actions, which emerged in the aftermath of the British Empire. Sourced and developed by IDS Librarians and Fellows between the mid-1960s and early-2000s, this re-developed historical collection comprises 250,000 items in 56 languages, from 150 countries.

The type of material includes government reports, censuses, newsletters, journals, books, pamphlets and other ephemera. The subject areas include all aspects of development studies, most notably economics, population and family planning, education, and health. It provides an unparalleled resource for better understanding the global postcolonial history of development.

Following the closure of the IDS Library in 2017 due to funding cuts, and a period of uncertainty and dormancy for the collection, in 2019 a £400,000 Wellcome Trust grant was awarded jointly to the UoS Library and IDS to improve its accessibility, with the aim being to create an invaluable and enduring research resource for a new generation of scholars. Thanks to the meticulous work of Caroline Marchant-Wallis, Danny Millum and colleagues over the past 3 years, the material has been preserved and catalogued, and is now being promoted and accessed. It has a dedicated website and can be browsed by theme or country via the University of Sussex Primo Library discovery platform.

The value of the BLDS Legacy Collection lies in both the breadth and scope of its contents, and the fact that the collection primarily derives from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) in the Global Majority, where limited funds and digital infrastructure, conflict, and/or environmental disasters have often led to substantial archival destruction. Amidst current concerns to decolonise both development studies and librarianship, the collection contains a wealth of research data latent with potential to (re)generate and diversify global knowledge connections. I’m interested in what kind of (de)colonial stories this data might tell.

Here’s a video clip of Danny talking about the collection and our metadata mapping pilot project, part of a lightning talk that he, Tim and I delivered for the CILIP Metadata Discovery Group annual conference earlier this month.

Sussex and IDS and their libraries were developed in the early 1960s at significant historical juncture of geopolitical change, with the forces of international development and decolonisation being shaped by neo-colonial logics of nation-building and knowledge-building. As the quote that opens this blog post illustrates, a key lens for my research is the vision of University of Sussex’s founding father Professor Asa Briggs to ‘draw a new map of learning’ via interdisciplinary schools of study and degree programmes, reflecting shifting geopolitical landscapes of knowledge and nationhood in a the rapidly changing global context of the Cold War and development agendas around decolonisation of Commonwealth nations.

Archival documents from early 1960s working party committee meetings on the establishment of the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) at Sussex clearly show how the “key to the success of the institution” was the development of its library collections, which were developed via close relationships with the Colonial Office Library and Ministry of Overseas Development, with ”ancillary libraries available material for the study of development administration on a world-wide scale.” As one committee member argued, the need for this was urgent since “…if action is not taken promptly, Britain will no longer hold its position as a centre where there is available material for the study of development administration on a world-wide scale.”[ii]

The earliest records in the BLDS Legacy collection are from the 1860s, a century before IDS was established, which demonstrates the legacy connections with the former Colonial Office libraries and government administrations in the British colonies. The collection really explodes in size and types of documentation in the second half of the 20th century, with many items from liberation groups and organisations, highlighting the material culture and epistemic tensions of anti-colonial struggles and decolonial development.

I want to find out why and how these collections were acquired across these time periods and geographic regions, who used these documents, and for what purposes, throughout the institutional evolution of IDS and Sussex. Interactive maps are a really helpful and dynamic way of informing these research questions and connections as I interview IDS and Sussex alumni. My research methods are very qualitative, so I turned to colleagues like Tim and Danny to ask for help in exploring the more quantitative aspects of collections data. When I discovered they were experimenting with visual mapping prototypes to visualise BLDS Legacy collection, this was music to my ears and we began collaborating on how to develop these tools, with me being the person to ask lots of pertinent questions about why and how the collections data is configured the way it is.

Our collaborative BLDS metadata mapping experiments were spearheaded by the ingenuity of our interdisciplinary colleague Dr Ben Jackson, Research Fellow in Digital Humanities and the Library, whose expertise in Heritage Informatics and big data mapping enabled him to generate an alternative to the traditional library catalogue digital interface. Ben created a prototype interactive world map visualising all the catalogued items in the BLDS Legacy Collection based on the catalogue metadata fields for publication date and country of origin.

The resulting digital atlas displays the density of BLDS Legacy records associated with any one place in the world at any given historical point on the collection timeline. The interface also documents the number of records that have no geographic location data associated with them on the catalogue, which can read as forms of archival absence, an important concept in decolonial information studies [iii]

Armed with Ben’s coding formulas, Tim developed the maps from 2D atlas visualisations to 3D globes. Along the way, he encountered some puzzling issues that highlight colonial epistemic legacies hidden within the ways in which the collection metadata has been catalogued over time. Here’s Tim demonstrating this in his segment of the lightning talk video.

Tim’s 3D visualisation displays publications from countries like towering stacks, offering an instant understanding of data distribution across global territories. Tim’s visual exploration faced challenges due to inconsistencies in ‘MARC’ data. For instance, differences in country of publication naming conventions, like Rhodesia’s old name versus its present-day Zimbabwe, became problematic. This inconsistency complicates search functionalities, presenting a puzzle Tim believes might be solved with linked data in the future.

My first impressions of these metadata mapping visualisations underlines for me the importance of understanding not just the quantity but also the quality and origins of these collections items. The way the content is catalogued, through the Eurocentric prism of Library of Congress classification system and MARC21 bibliographic metadata coding, must be critically examined.

The original BLDS collection under the management of former IDS Librarians, did not use these Eurocentric ‘universal’ cataloguing and classification systems, but rather a bespoke catalogue that was tailored to the uniqueness of the collection and the needs of its users. This system of knowledge organization may also be subject to decolonial critique, however we can only speculate on this, as this institutional memory was lost when the library closed and the librarians were made redundant.

Here’s a clip from my segment of our conference lightning talk, in which I reflect on these epistemic (in)justice conundrums.

To add to my conclusion in this video, I will end this blog post on this thought: mapping collections is by no means an exact science; it is an experiment populated with the ghosts of imperial territories and dominions of knowledge building. On this we can gain wisdom from the most enigmatic of librarian-storytellers, Jorge Luis Borges [2]:

In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied the entirety of a City, and the map of the Empire, the entirety of a Province. In time, those Unconscionable Maps no longer satisfied, and the Cartographers Guilds struck a Map of the Empire whose size was that of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. The following Generations, who were not so fond of the Study of Cartography as their Forebears had been, saw that that vast map was Useless, and not without some Pitilessness was it, that they delivered it up to the Inclemencies of Sun and Winters. In the Deserts of the West, still today, there are Tattered Ruins of that Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in all the Land there is no other Relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

Jorge Luis Borges, 1946

Notes

[1] My Library teaching and fellowship roles at UoS Library will end on 30th September, and on 1st October I will commence a three year Leverhulme Early Career Fellowship in the Sussex School of Global Studies.

[2] This one-paragraph short-story by Borges titled On Exactitude in Science, published in 1946, is credited fictionally as a quotation from “Suárez Miranda, Viajes de varones prudentes, Libro IV, Cap. XLV, Lérida, 1658″.

References

[i] Ashley Glassburn Falzetti, ‘Archival Absence: The Burden of History’, Settler Colonial Studies, 5.2 (2015), 128–44; Pamela VanHaitsma, ‘Between Archival Absence and Information Abundance: Reconstructing Sallie Holley’s Abolitionist Rhetoric through Digital Surrogates and Metadata’, Quarterly Journal of Speech, 106.1 (2020), 25–47; Archival Silences: Missing, Lost and, Uncreated Archives, ed. by Michael S. Moss and David Thomas (London ; New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2021).

[ii] ‘Memorandum on possible procedure for developing and exploiting Afro-Asian library materials in the University of Sussex.’ M.H. Rogers, Subject Librarian, 8 June 1965. (University of Sussex Collection SxUOS1/1/3/5/11/13, The Keep).

[iii] In David Daiches, The Idea of a New University: An Experiment in Sussex (London: Andre Deutsch, 1964), p. 66.

Leave a Reply