Writes Sussex alumna Maddie Hunt, (BA Geography and International Development 2023)

*The views in the following article are the personal views of the author and are not an official position of the School.*

If someone asked you ‘how much corn do you eat’? you would probably be racking your brain trying to remember the last time you cracked open a tin of sweetcorn. Or maybe you mind would go straight to popcorn at the cinema, or even the tacos you had last time it was Mexican night. Your first thought probably wouldn’t be the High fructose corn syrup (HFCS) found in a whole host of sugary snacks and highly processed food items. HFCS is a derivative of corn starch which comes from the maize crop, and is a popular sugar alternative, particularly in the U.S where Americans are consuming it in larger quantities than ever before. Corn is present in US diets in ways that people aren’t even aware of – fruit juices, condiments, ice cream, breakfast cereals, crackers, and breads. While palm oil may be a more common ingredient in ultra-processed foods in the UK, there is much we can learn from how these processed and pre-packaged items take staple crops and turn them into something different altogether.

Corn, otherwise known as maize (Zea mays), is currently grown in greater volume than any other crop in history. In 2018 the production of maize was over 1,140 million tonnes, followed by rice (782 million) and wheat (734 million) (Dai, Ma and Song, 2021). Maize today is a staple food for more than 1.2 billion people and meets a third of calorie needs in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Sub-Saharan Africa. However, the United States is the world’s largest corn producer and consumer, planting an average of 90 million acres of corn each year. Over half of this is used as livestock feed or turned into ethanol, while the rest is processed into sweeteners, corn oil, and industrial alcohols,. With the help of biotechnology introduced in the 20th century, farmers were able to produce a maize crop that was high yielding and more starchy, but lower quality in terms of taste and nutritional value. In other words, perfect for producing corn syrup, low-cost animal feed, and fuel. However, corn was not always utilized in this way, and the story of its domestication and subsequent domination in our food system is one of livelihood struggle, silenced voices, and neoliberal politics. To understand the ubiquity of modern maize and its cultural significance, we need to start at the roots. Where did maize come from? How was it commercialised? And why was this evolution so detrimental to the people that started farming it in the first place?

Where it all began: the start of maize

There is a general consensus that maize originated in central Mexico about 7000 years ago (Ranum, Peña-Rosas and Garcia-Casal, 2014), and from what archaeologists understand, it was consumed in a variety of different ways across South America. In fact, according to a study by the Museum of Natural History in Washington, ancient Peruvians were consuming maize as popcorn around 6,700 years ago. Although the exact location is uncertain, maize cobs dating back to 5000 BCE were discovered in the Tehuacán Valley in the southeastern end of Puebla, prompting the region to be termed the ‘cradle of corn’ (Fitting, 2010). It has been suggested that there are several other locations where original maize domestication could have occured, and this continues to be debated as genetic research evolves. Nevertheless, we have strong archaeological evidence to suggest that maize is indeed from Mexico (Ranum et al. 2014).

via Flickr

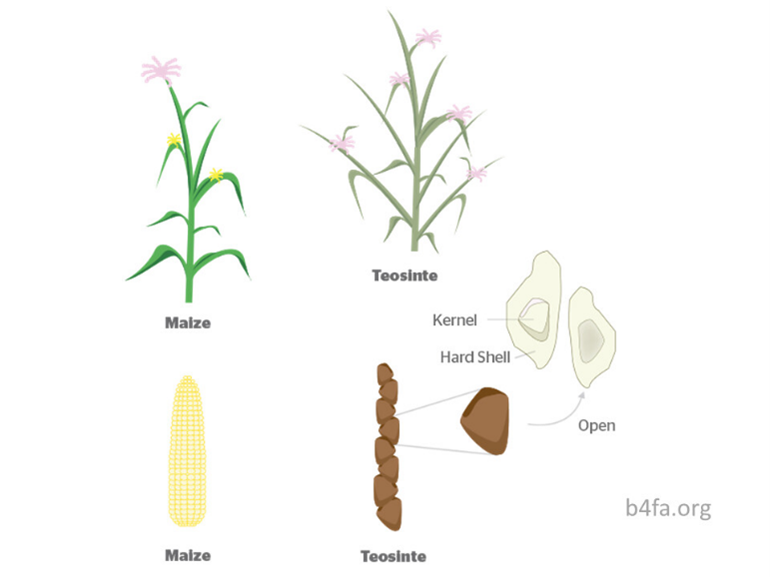

Since its discovery all those years ago, maize has undergone a dramatic transformation. Through centuries of domestication humans have turned corn into a crop that barely resembles its ancestor to make it more suitable for industrial food production. According to the USDA, maize started out as a wild grass called teosinte, a plant that differed from modern maize in many ways. Visually, it would have been quite different to the corn grown today – more bushy, more branches, and the seeds stacked on top of each other surrounded by a hard fruit case, making it difficult to harvest. Over thousands of years, by systematically cultivating the plants with the most desirable traits, Native Americans transformed maize into a viable food source (Ranum et al. 2014). Seed size was an important trait targeted in this domestication because it provided indigenous people with enough calories to feed them for an extended period of time, meaning they wouldn’t have to move locations as frequently (Ranum et al. 2014). Maize was spread by tribes in Central America to other regions of Latin America, the Caribbean and then up north to the US and Canada. In addition, maize was taken to areas of Asia and Africa by traders, and to Europe by European explorers (Ranum, et al. 2014). Due to its ability to adapt to different climates, altitudes, and day lengths, maize successfully spread across the world. In doing so, it crossed with other wild and cultivated varieties, eventually giving birth to locally adapted varieties known as landraces, relied on by communities for thousands of years.

Maize had become a dietary staple for many people in parts of Central and South America by about 3000 years ago, and was on the path towards high productivity (Blake, 2015).Fast forward a few thousand years, through a long process of artificial selection of desirable traits and cross breeding of landraces, we now rely on a handful of hybrid varieties of maize which have consistent kernels and high yields. The domestication of maize to suit the needs of mass production may seem like something to be celebrated, but this success in terms of yield, has come at a cost.

Adios Mexican maize, howdy American corn!

Thanks to the advances in high-yield crops, a staggering 99% of corn grown in the US today is from hybrid seeds. These trends, however, stretch beyond the country’s borders. Since the 1930s, Mexico has lost 80% of its maize varieties, leaving us with a fragile genetic base buttressing our entire food system. The industrialisation of maize production, facilitated by agricultural trade liberation, has a major part to play in this genetic diversity loss. Research shows that the use of local landraces has been decreasing in recent decades, specifically in areas where there has been a shift from subsistence to commercial agriculture (Keleman, 2010).

Small-scale farming in Mexico has been hugely impacted by neo-liberal economic policies such as the North American Free Trade Agreement, universally known as NAFTA, implemented in 1994. This trilateral trade agreement had a momentous socio-economic impact on rural Mexico, particularly affecting the livelihoods of maize farmers (Wise, 2007). NAFTA was the catalyst for financial struggles felt by millions of Mexico’s small-scale maize producers and many were forced to abandon their farms completely due to economic pressure from rising imports of US corn (Wise, 2007). Under regulations designed to boost economic growth, import restrictions on maize were scrapped and full trade liberalisation took place, resulting in US corn imports three times greater than they were pre-NAFTA. Subsequently, corn prices dropped by almost half and rural migration rates were drastically on the rise (Wise, 2007). Agricultural liberalization under NAFTA also made it more difficult for small-scale farmers to adapt to periods of environmental or market change, meaning that genetic diversity conservation projects run by communities were unlikely to be fruitful. The inflated rates of rural poverty due to failure of neoliberal policies to protect small-scale farmers and the loss of genetically diverse maize varieties are two of the most significant problems that post-NAFTA Mexico must face, and both are intimately linked.

When industrially produced US corn waltzed into the Mexican maize market, not only were livelihoods under threat, but so was the genetic heritage of maize. This was not only because rural farmers were forced to produce maize as a commodity for export, but because locally adapted landrace varieties, which have taken thousands of years of evolution, were contaminated by genetically modified US corn (Wilson, 2012). The cross-pollination of imported US transgenic corn with local landraces has the potential to seriously damage the region’s agro-biodiversity, according to anthropologist Elizabeth Fitting, who writes extensively about what she terms the ‘neoliberal corn regime’ (Fitting, 2010). This regime, in bulldozing rural farming and replacing it with industrialised agricultural methods has created losses that are environmental, economic, and cultural.

Corny diets and neoliberal nutrition

Maize diversity | Maize ears from CIMMYT’s collection, showi… | Flickr

The deterioration of traditional farming, and genetic diversity of maize were not the only consequences of the commercialisation of farming in Mexico. Modern-day maize production threatens to deepen food insecurity and worsen nutritional outcomes for the communities that cultivate maize, as well as the wider population who consume products made with the nutritionally inferior US corn. The birthplace of the maize crop has witnessed a long process of domestication, contamination of GMOs, loss of traditional landraces and an overall loss of species diversity. This brings us to the corn we know today – yellow, high yielding, large kernelled, and perfect for processing. Corn in the 21st century seems to be merely a commodity, but this is not the case for many parts of Meso-America. For many indigenous groups, the maize plant represents the origin of life, (Keleman, Hellin and Bellon, 2009) and is still an essential part of the Mexican diet for both rural and urban consumers alike, particularly the poor (Bellon and Hellin, 2011). Tortillas are one of the most common ways that corn is eaten in Mexico today, but now the consumption of tortillas is hitting a record low, mainly due to the convenience and lower prices of processed, pre-packaged foods. The diminishing demand for tortillas represents a shift facilitated by globalisation away from traditional diets towards fast foods.

Rafael Mier is the founder of an activist non-profit organisation called Organización de Tortilla de Maíz Mexicana, which aims to educate people in Mexico about tortillas and indigenous corn species. He believes that Mexico is in a corn crisis and hopes to raise awareness about the dwindling maize diversity, informing people that the country’s heirloom corn varieties are heading towards extinction10. Another organisation known as IXIM (meaning corn in the indigenous Mayan language of Tzeltal) is working to build resilience in the southern state of Chiapas by encouraging farmers to become more self-reliant rather than buying imported products. Through helping local farmers find buyers for their harvests, IXIM are facilitating the growth of indigenous corn species and thereby increasing the availability of diverse species of corn for the whole community10. Not only is corn less diverse and lower in nutritional value, but people are also generally consuming less of it due to the uptake of highly processed convenience foods, which are steering people away from traditional dishes. This is having adverse impacts on health outcomes in Mexico, and a 2017 study based in south American found that two thirds of the population of Mexico are either overweight or obese. Nutrition experts are mainly pointing towards high fructose corn syrup as the culprit of these changes, especially regarding increases of chronic diseases such as diabetes. A study found that countries with higher availability of HFCS have a 20% increased rate of type 2 diabetes (Goran, Ulijaszek and Ventura, 2013).

It has been assumed that supposed rise in income associated with commercial production would contribute to improved levels of nutrition amongst rural families, but this has not necessarily been the case. A study of rural families in Tabasco assessed how the transformation from smallholder farming to modern commercial agriculture impacted the nutritional status of children (Dewey, 1981). This study was based in the Chontalpa area, which has seen a significant change in farming practices away from traditional farming, associated with self-sufficiency, towards growing crops for export, which is associated with higher reliance on store-bought foods. Kathryn Dewey (1981) highlights that when food is produced for home consumption, the goal of the grower is to cultivate diversity to ensure a varied and nutritious diet, whereas when production is solely for an exchange value, the cash received may be insufficient to support a diet of adequate nutrition. Overall, the study (which uses a nutritional survey of 149 rural families) finds that the nutritional status of preschool children is negatively associated with lower crop diversity and increased dependence on purchased foods (Dewey, 1981). As with so many shifting diets across the world, this highlights the risks of relying on highly processed, store-bought food products and the benefit of consuming a diversity of foods, based on local production. While Mexico provides a similar cautionary tale, it also points to potential alternatives.

The fight back

In resistance to the poor conditions created by NAFTA, and more generally in opposition to globalisation and the rise of neoliberalism, an indigenous armed organisation called The Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) was formed. The struggle for indigenous autonomy is deep rooted in Mexico’s history, but in 1994 the EZLN declared war on the Mexican government to end segregation and oppression of indigenous communities. The EZLN is predominantly made up of people from diverse indigenous communities in Chiapas, a southern Mexican state. In terms of natural resources, Chiapas is one of the wealthiest states in Mexico, but the indigenous population of over 1.1 million suffer some of the highest levels of marginalisation in the country. Over 50% of the indigenous population of Chiapas report having no income at all, according to International Service for Peace, and 42% make less than $5 per day. The state’s economic crisis is considered to have been the most severe during the period from 1970 to 2000, a period which saw the demise of the plantation economy due to declining commodity prices and soaring cost of inputs (Washbrook, 2007). Since Mexico’s transition from a state-led to a market-orientated economy towards the end of the 20th century, social movements such as the Zapatista uprising have empowered civil society and given a sense of hope to Indigenous communities who have suffered social injustice for so long.

The Zapatistas provided a blueprint for rejecting the imposition of neoliberal markets, methods and diets, and indigenous rights were yet again put to the forefront in 2002 when a broad coalition of Mexican environmentalists, indigenous rights groups and campesinos (peasants) established the ‘In Defence of Maize’, campaign (Wilson, 2012). In Defence of Maize recognises that the debate is not merely an argument concerned with the risks associated with yield and agricultural (bio)technology, but one which is innately tied to the cultural significance of traditional farming, the consequences of neoliberal trade policies, and the dismissal of indigenous knowledge (McAfee, 2008). By challenging the delegitimisation of traditional and agroecological methods in national debates, the campaign brings much needed attention to rural social movements calling for ecologically informed farming practices and places their demands before capital.

Despite significant losses in maize varieties – not all diversity has been lost. There are still many traditional landraces found in Latin America, and gene banks such as the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT) near Mexico City hold thousands of samples of traditional maize. Importantly, it is the small-scale producers in Mexico who are largely responsible for the maintenance of maize diversity, cultivating over 40 distinct landraces and supporting the country’s agro-biodiversity (Wise, 2007). In situ conservation of genetic diversity is also vital for crops to evolve and adapt to changing climatic conditions and new diseases, which is not possible in germplasm banks (Dyer et al., 2014). The Mexican government now requires the political will to support maize farmers and protect vital agricultural biodiversity by building polices based on values that already exist in traditional farming (Wise, 2007).

Corn today, gone tomorrow

Regardless of how it is being consumed, maize is a vital source of life. Humanity now relies on only three plant species for 50% of its calories, maize being one of them. Over time we have indulged in more than 6,000 plant species to satisfy our hunger, but transformation of agriculture has led to the dominance of a tiny fraction of these plants, and the extinction of many others, leading to a uniformity in our diets that is unprecedented.

We can observe this lack of diversity in more than just the grains we grow. Homogeneity is the norm in what we eat – half of the world’s cheeses are produced with enzymes manufactured by a single company, and global pork production is based on the genetics of a single pig. The globalisation of food production has thus given us the paradox of choice; it seems as though we are eating a higher variety of foods than ever before. After all, we can eat whatever we want whenever we want. But the reality is that all over the world, our diets have become unified, and we are all consuming the same foods, from the same genetic base. This dependence on such few plant species puts humans in a very precarious position – in 1970 a disease called Southern Corn Leaf Blight wiped out 15% of maize crops in the US and southern Canada, with overall losses estimated at 1 billion US dollars. This outbreak was the result of the exposure of a widely grown hybrid maize variety (which had a vulnerable common genetic background) to an infectious pathogen in environmentally favourable conditions (Bruns, 2017). This was a disastrous epidemic for North American agriculture, but an important lesson regarding crop species diversity. It is imperative to grow more than just a single hybrid variety of corn if we want to prevent a maize apocalypse. Plant diversity helps spread the risk of disease because certain varieties are resilient to certain pathogens, meaning we are able to preserve at least a portion of our essential food source if another outbreak were to occur. The same goes for our two other life-supporting grains wheat and rice; both of which were whittled down to a few varieties during their process of ‘modernization’ to meet our calorie demands.

The future of food is uncertain, but one thing we can say for sure is that there is no future of Mexico without maize. There are people fighting to protect and preserve the heritage of maize and remind us of the cultural power the crop holds in Mexican society. Organisations such as Organización de Tortilla de Maíz Mexicana and IXIM are doing vital work to raise awareness of the threat to corn species diversity and provide support to local farmers. The promotion of landrace corn varieties is a step in the right direction towards securing the future of Mexican maize and giving power back to the indigenous communities whose voices have been silenced and cultivation practices disregarded. The battle is far from over, and it remains pertinent to ask: will we further transform our food system to protect crop species diversity and sustain human life on earth, or will we eat ourselves to extinction? Either way, maize remains a large piece of the food system puzzle, and maybe you will think about its story the next time you are at a barbeque and someone offers you a corn on the cob.

This blog was written as part of the third-year International Development module ‘Political Ecology and Environmental Justice’.

References

Bellon, M.R. and Hellin, J. (2011) ‘Planting Hybrids, Keeping Landraces: Agricultural Modernization and Tradition Among Small-Scale Maize Farmers in Chiapas, Mexico’, World Development, 39(8), pp. 1434–1443. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.12.010.

Blake, M. (2015) ‘The Archaeology of Maize’, in Maize for the Gods. 1st edn. University of California Press (Unearthing the 9,000-Year History of Corn), pp. 17–36. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctv1xxzkr.6 (Accessed: 6 April 2023).

Bruns, H.A. (2017) ‘Southern Corn Leaf Blight: A Story Worth Retelling’, Agronomy Journal, 109(4), pp. 1218–1224. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2134/agronj2017.01.0006.

Carro-Ripalda, S. and Astier, M. (2014) ‘Silenced voices, vital arguments: smallholder farmers in the Mexican GM maize controversy’, Agriculture and Human Values, 31(4), pp. 655–663. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-014-9533-3.

Dai, D., Ma, Z. and Song, R. (2021) ‘Maize kernel development’, Molecular Breeding, 41(1), p. 2. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11032-020-01195-9.

Dewey, K.G. (1981) ‘Nutritional consequences of the transformation from subsistence to commercial agriculture in Tabasco, Mexico’, Human Ecology, 9(2), pp. 151–187. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00889132.

Dyer, G.A. et al. (2014) ‘Genetic erosion in maize’s center of origin’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(39), pp. 14094–14099. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1407033111.

Fitting, E. (2010) The Struggle for Maize: Campesinos, Workers, and Transgenic Corn in the Mexican Countryside. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Goran, M.I., Ulijaszek, S.J. and Ventura, E.E. (2013) ‘High fructose corn syrup and diabetes prevalence: A global perspective’, Global Public Health, 8(1), pp. 55–64. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2012.736257.

Keleman, A. (2010) ‘Institutional support and in situ conservation in Mexico: biases against small-scale maize farmers in post-NAFTA agricultural policy’, Agriculture and Human Values, 27(1), pp. 13–28. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-009-9192-y.

Keleman, A., Hellin, J. and Bellon, M.R. (2009) ‘Maize diversity, rural development policy, and farmers’ practices: lessons from Chiapas, Mexico’, The Geographical Journal, 175(1), pp. 52–70. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4959.2008.00314.x.

McAfee, K. (2008) ‘Beyond techno-science: Transgenic maize in the fight over Mexico’s future’, Geoforum, 39(1), pp. 148–160. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2007.06.002.

Ranum, P., Peña-Rosas, J.P. and Garcia-Casal, M.N. (2014) ‘Global maize production, utilization, and consumption’, Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1312(1), pp. 105–112. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12396.

Washbrook, S. (2007) Rural Chiapas Ten Years after the Zapatista Uprising. Oxford: Routledge.

Wengronowitz, R.J. (2013) ‘Elizabeth Fitting: The struggle for maize: campesinos, workers, and transgenic corn in the Mexican countryside’, Agriculture and Human Values, 30(3), pp. 483–484. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-013-9454-6.

Wilson, A.B. (2012) ‘Elizabeth Fitting: The Struggle for Maize: Campesinos, Workers, and Transgenic Corn in the Mexican Countryside’, Human Ecology, 40(2), pp. 331–333. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-012-9467-6.

Wise, T.A. (2007) ‘Policy Space for Mexican Maize:Protecting Agro-biodiversity by Promoting Rural Livelihoods’, GDAE Working Papers [Preprint]. Available at: https://ideas.repec.org//p/dae/daepap/07-01.html (Accessed: 7 April 2023).

Leave a Reply