23 June 2017

L. Alan Winters CB, Professor of Economics and Director of UKTPO and Ilona Serwicka, Research Fellow at UKTPO

One year ago the British people voted to leave the EU. Out of 33.5 million votes cast, 51.9 per cent were for ‘leave’, albeit in the absence of any statement about what ‘leaving’ might mean. The government is still vague about what the UK’s post-Brexit trade policy should be – even after triggering the formal leave process – but the general election has pressured Theresa May to soften her Brexit stance. Even though Brexit negotiations are now formally under way, the options suddenly again seem wide open for debate.

In terms of options the UK is back at square one, but following a year’s analysis, it is now clearer what these options amount to. Over the year, the UK Trade Policy Observatory (UKTPO) has discussed many of the options and this note draws on some of that analysis to try to light the path forward.

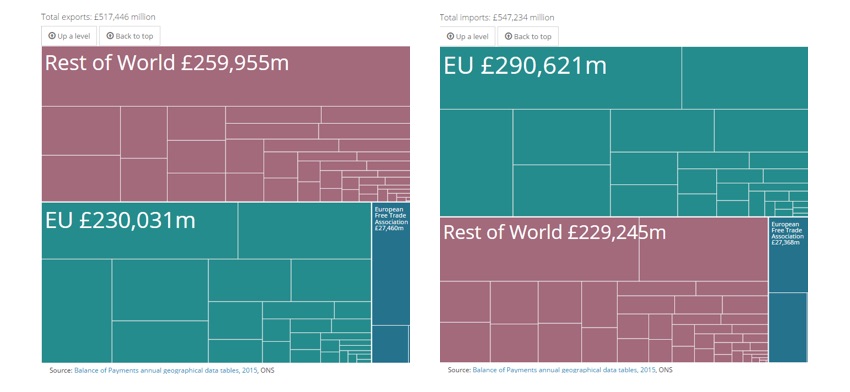

Trade with the EU accounted for 44 per cent of total UK exports and 53 per cent of total UK imports in 2015. All of this was carried out with zero tariffs and with very low non-tariff barriers courtesy of the Single Market. The EU is large, rich, close and similar to the UK; it will inevitably remain a hugely important trading partner.

In 2015 services accounted for 43 per cent of the UK’s total exports and 24 per cent of the UK’s total imports. The UK runs a sizeable trade surplus in services – equivalent to some 5 per cent of the national income.

The UK has a hung Parliament and suddenly it has become acceptable again to talk about membership of the European Single Market and/or the Customs Union and the nature of a possible Free Trade Agreement. No-one has actively advocated ‘no deal’ – but even that cannot be ruled out because the complexity and contentiousness of Brexit may prevent reaching an agreement in time. What do these options entail?

The European Single Market is a ‘regulatory union’ that covers both goods and services. Because members of the European Single Market apply equivalent regulations (and this is enforced by a strong common legal system culminating at the European Court of Justice, ECJ), goods and services that satisfy one member satisfy the rest; there is no need to check at the border that imported goods conform with required standards, and purchasers of services can be confident of redress should anything go wrong with their transactions. Based on the Single Market, EU members have progressed further towards integrating their services markets than any other multi-country group.

The EU’s stated view is that membership of the European Single Market – restricted to EU Member States, plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland – is not compatible with a dilution of the freedom of movement of labour.

The UK could try to negotiate a new Customs Union (CU) with the EU, which would apply to trade in goods but not in services. Such a Customs Union would commit the UK to zero tariffs on trade with other EU Member States and a common external tariff with non-EU countries, including having the same set of free trade agreements as the EU has with non-EU countries. This would mean that the UK could not have an independent trade policy for goods.

To maintain the freedom to negotiate its own goods trade deals with third countries, the UK could opt for negotiating a new Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU, which would keep UK-EU tariffs at zero. Because the FTA members can set different tariffs on goods originating from third countries, an FTA would also require the efficient control and application of Rules of Origin (ROOs) on the UK-EU border in order to distinguish between goods originating within the FTA (which pay zero tariffs) from those originating in third countries, which pay a tariff.

In both the CU and FTA cases, the UK would be free to negotiate agreements with third countries on trade in services.

This is the ‘hard Brexit’ scenario, whereby UK-EU trade is subject to the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) terms that they have agreed with WTO members – sometimes referred to as ‘WTO rules’. There would be high tariffs on trade in certain goods (e.g. cars), high regulatory barriers to trade in many goods including incurring the costs of testing and certification that UK goods meet EU standards (and vice versa), and high regulatory barriers to services trade, such as requiring banks to hold reserves within both the UK and the EU and limiting the right of lawyers to practice in other countries.

If the rejection of the free movement of labour, freedom from the jurisdiction of the ECJ and freedom to negotiate new trade deals with third countries are political ‘red lines’ for the UK, the most attractive feasible Brexit outcome would be a new (deep and comprehensive) Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU-27 with a variety of special sectoral arrangements. But a deep UK-EU FTA cannot be achieved in 21 months – and even a weaker agreement would still take more than 21 months to negotiate. The UK will thus need a transitional agreement with the EU-27. This has to be simple model that can be adopted without much negotiation (it is necessary precisely because there is no time for negotiation), and something close to the status quo will minimise a disruption.

Some new investment will be needed even if the UK negotiates a new CU (for example, to check compliance with standards and levy Value-Added Tax) or a new FTA (to efficiently control and apply the ROOs). And in any case, the UK will need to work in close cooperation with the EU to smooth the passage of goods to the maximum extent possible.

Different sectors depend on the CU and SM to different extents and so, depending on what follows, will be disrupted to different degrees by leaving them. Because different regions have different sectoral profiles and different degrees of dependence on EU links within sectors, any disruption to EU trade will have quite heterogeneous effects.

Negotiations to ‘regularise’ the UK’s position in the WTO and to establish a new trade relationship with the EU-27 are the most urgent issues. Until these are settled no other significant trading partner is likely to want to sign an FTA. The WTO relationship defines the UK’s ‘default’ trade policies that an FTA would seek to improve upon, and the EU relationship affects the probable value of getting access to the UK market.

The UK is a member of the WTO and does not need to reapply on leaving the EU, but it does need to separate a UK schedule of commitments from the EU schedule. While this is generally straightforward there are some gritty little details in agriculture that need to be settled. This is a job for diplomacy.

One further complication is that leaving the EU will cause the UK to lose its membership of the WTO’s Government Procurement Agreement (GPA). Negotiating accession is desirable both to keep UK procurement markets open to competition from abroad and to give UK firms access to other members’ markets. Designing its own procurement policy will also provide the opportunity to improve procurement policy in the UK.

In both these cases, Brexit will also disturb the EU’s relationships within the WTO. Hence finding solutions will be easier cooperatively, and a joint UK-EU diplomatic effort in the WTO could provide a useful balm for the negotiating rivalry that will define most of their interactions over the next two years.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex.

Republishing guidelines

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to he original resource on the our website. We do not however, publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

[…] to square one?Even though Brexit negotiations are now formally under way, the options for Brexit still seem wide open for debate, although it is now clearer what these options amount to, according […]