1 April 2019

1 April 2019

Dr Ingo Borchert is Senior Lecturer in Economics and Julia Magntorn Garrett is a Research Officer in Economics at the University of Sussex. Both are fellows of the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

During the first round of the indicative voting process at Parliament, the motion that proposes a permanent customs union attracted the second highest number of Ayes and was rejected by the slimmest margin of all eight motions. This result shows the prevailing preoccupation with trade in merchandise goods. Amongst other things, a customs union alone does nothing for services trade. In this blog, we set out why the continued neglect of services trade is a major concern for the UK economy.[1] A twin-jet aircraft with just one engine on would ordinarily be bound for an emergency landing rather than for a smooth journey ahead.

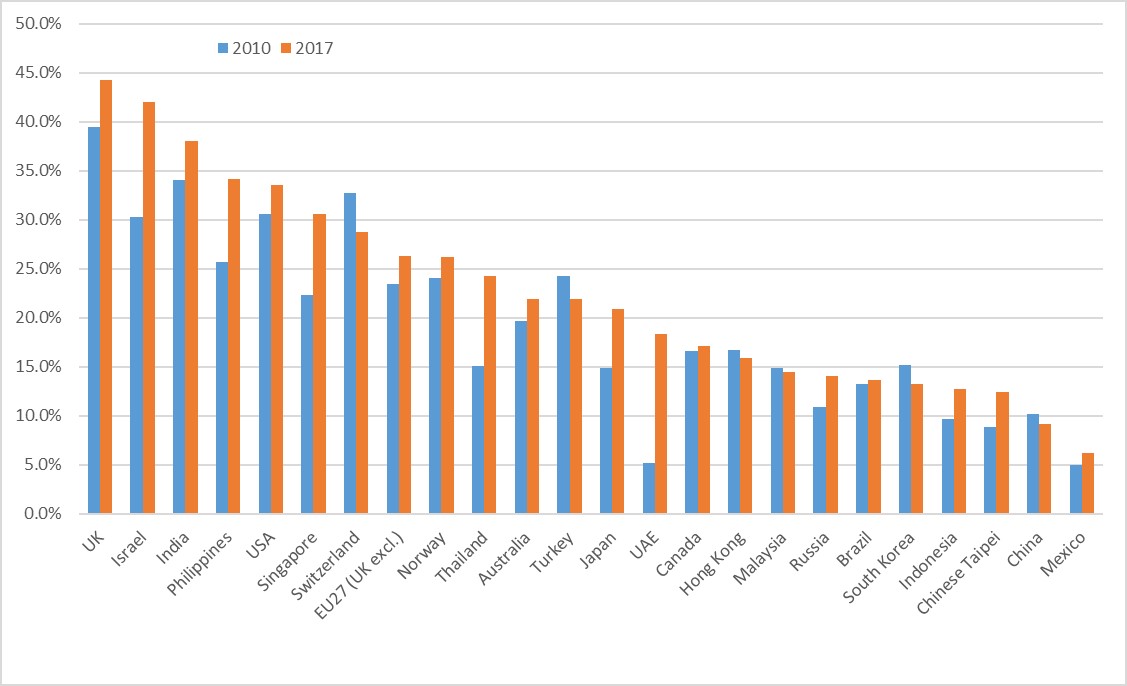

It is sometimes noted that the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world in spite of not being the second largest economy in the world. Yet even this statement does not do justice to the salience of services exports for the UK. In fact, the UK is the most services-export-intensive country of any major economy in the world. What does this mean? When looking at the combined value of services and goods exports, services account for nearly one half (44.3%) of total UK exports in 2017. In global comparison, this is an extraordinarily high share. It actually puts the UK right at the top of the league table of the 25 largest services exporters in the world (Figure 1). For instance, the UK share of services exports is appreciably higher—by 11 percentage points—than the corresponding share in the United States (33%) or the EU average share excluding the UK (26%). The same top spot for the UK obtains when only ‘Other Commercial Services’ exports are considered, which would exclude Transport services and Travel, respectively.

The UK economy has not always been in this position. Rather, the salience of services for UK exports is the result of a secular rise in the share of services in total trade over two decades. This share was only about 25% at the beginning of the 1990s, much in line with the stylised fact that services trade typically accounts for about one-fifth of the value of exports. Yet, from that point in time, the UK share rose to nearly 45% in 2017.

Figure 1: Share of Total Services Exports in Total Exports, 2010 and 2017

Source: WTO Services Trade Statistics as of February 2019. Total Exports denote the sum of services and merchandise goods exports, respectively. Macao excluded from the graph.

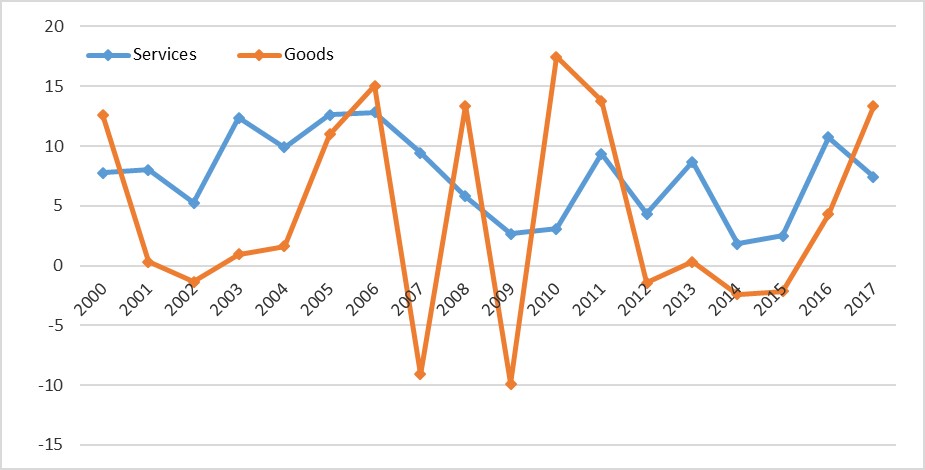

Not only are services uniquely important for the UK in terms of export magnitudes, services exports also exhibit higher and more stable growth rates. This became most apparent during the recent global financial crisis of 2007-10, as services exports proved much more resilient than goods trade. Figure 2 shows that, during the crisis, the value of goods exports fell massively in 2007 and 2009. During the same period, services exports continued to grow, albeit at temporarily lower rates. The reasons are manifold – ranging from not being dependent on trade finance to a presumably lower demand elasticity – but in any event services exports proved considerably more stable during times of economic distress.

The relatively less volatile performance of services exports was also accompanied by more buoyant growth. Over the entire period 2000-17 depicted in Figure 2, UK services exports grew at an average annual rate of 7.4% as opposed to the average growth rate for goods exports of 4.0%. Clearly, resilience and growth rates are related. The lower average growth rate of goods exports is at least in part a consequence of its higher susceptibility to economic fluctuations.

Figure 2: Annual Growth Rates of UK Goods and Services Exports, 2000-2017

Source: ONS Pink Book 2018, Chapter 9. Authors’ calculations.

The success story of services comes from a combination of structural factors as well as policy reform, especially in the European context. As for the former, many services are relatively skill-intensive to produce compared to goods, and the UK’s highly skilled workforce – not all of whom are UK nationals – have contributed to the services success story. In addition, (and this is a major factor for the London and South East region) certain service sectors also benefit from co-location with other service activities, such as professional business services related to finance and insurance, or the creative industries that cater for various aspects of the digital economy.

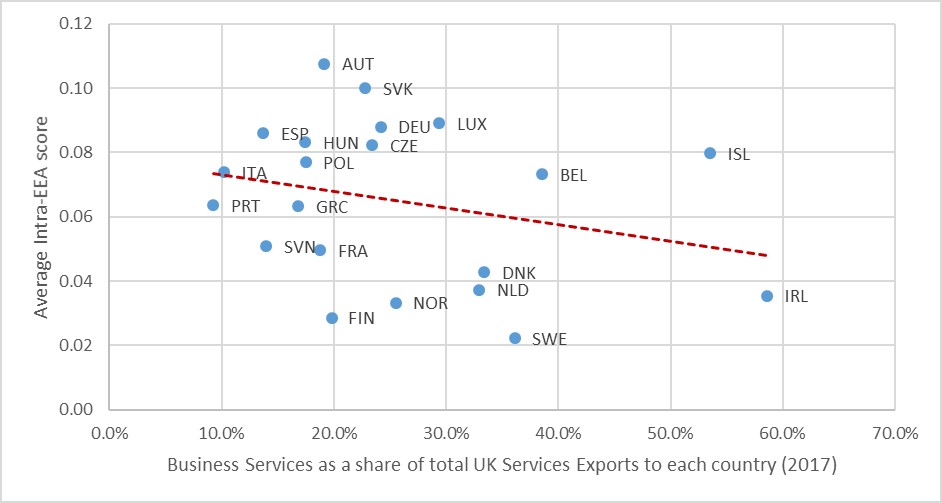

At the same time, policy efforts to facilitate services trade have been equally important. The international integration of service activities within the EU Single Market has enabled the UK’s position as a services exporter in a major way. This can be seen ever more clearly since the OECD has recently published a measure of services trade policy restrictiveness that would distinguish between policy barriers that apply to providers from outside the EU (say Japan) versus those from inside the EEA such as the UK.[2] One headline result from these new data is that, according to the OECD’s methodology of quantifying trade policy restrictiveness, the impediments for service suppliers from outside the Single Market are nearly four times as high as for a supplier domiciled within the EU (see Alan Winters: “Not Fit for Service: The Future UK-EU Trading Relationship”).

This advantage of being inside the Single Market is particularly pronounced across a range of regulation intensive professional services sectors such as legal advice, accounting, or engineering. UK professional services providers have clearly taken advantage of these liberalisation efforts. Figure 3 shows that the share of ‘business service exports’ in total services exports per destination country is higher the more open this particular trading partner is in terms of services trade policies (i.e. the lower the intra-EEA services trade restrictiveness score on the vertical axis).[3] For instance, Ireland exhibits an intra-EEA STRI of only 0.035, i.e. policy barriers to exporting business services to Ireland are lower compared to most other markets, and partly as a result of this, 58.6% of all UK services that go to Ireland are in fact business services (Figure 3). That is, the behind-the-border regulatory measures encapsulated in the STRI make a material difference to the success ofUK services export.

Figure 3: Intra-EEA STRI and the Share of Business Services Exports in Total UK Services Exports, 2017

Source: Benz and Gonzales (2019) and ONS Pink Book 2018; authors’ calculations. Business services consist of Architecture, Engineering, Legal services and Accounting, and the average intra-EEA STRI across these sectors is a trade-weighted average using 2017 UK export values in these sectors. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania are omitted from the Figure because no bilateral business services exports to these destinations are reported in the Pink Book 2018 as trade values are either disclosive or too small.

Given that conditions for exporting services to the EU are substantially more restricted for third-country providers (roughly, 4x more difficult) and that services make more of a contribution to overall exports in the UK than in any other economy in the world, future trading conditions for services matter for the UK. Better look after that other jet engine too.

[1] The ongoing ‘UK trade in services inquiry’ by the House of Commons International Trade Committee is a notable exception.

[2] Benz and Gonzales (2019), “Intra-EEA Stri Database: Methodology and Results”, OECD Trade Policy Papers, No. 223.

[3] We use the share of business service exports in the UK total services exports to an individual economy in order to mitigate against the forces of gravity, which affect services exports much in the same way as they affect goods trade. For example, the reason that UK firms export a lot of business services to the Republic of Ireland has much to do with its geographic proximity as well as linguistic and cultural affinity. In order to isolate the effect of ease of exporting services to Ireland relative to other countries, we use business services’ share in total services exports to Ireland as gravity forces will affect both the numerator and the denominator of that share in roughly the same way.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

[…] cent of total UK exports, making it the most specialised exporter of services in the world – the corresponding EU average share, excluding the UK, is only 26 per cent (for the US it is 33 per cent). Though […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] totali dal 12% al 9% nel decennio pre-pandemia). Nessuno lo celebra, ma il Regno Unito lo è La seconda fonte più grande di servizi nel mondo. Né la nostra specializzazione nei servizi è alla base della nostra recente […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] δεν το γιορτάζει, αλλά το Ηνωμένο Βασίλειο είναι το δεύτερος μεγαλύτερος εξαγωγέας των υπηρεσιών στον κόσμο. Και η εξειδίκευσή μας στις […]

[…] Teil der Gesamtexporte 12 % bis 9 % im Jahrzehnt vor der Pandemie). Niemand außer England feiert Zweitgrößter Exporteur Dienstleistungen in der Welt. Unsere Servicespezialisierung ist nicht hinter unserer jüngsten […]

[…] fell from 12% to 9% in the decade before the pandemic). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our specialization in services is not behind our recent […]

[…] abfiel 12 % bis 9 % im Jahrzehnt vor der Pandemie). Niemand feiert es, aber Großbritannien ist das zweitgrößter Exporteur von Dienstleistungen in der Welt. Und unsere Dienstleistungsspezialisierung liegt nicht hinter […]

[…] exports has fallen) 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). Nobody celebrates it, but the UK is The second largest source of services in the world. Nor is our service specialization behind our recent underperformance: on […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialization does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports has fallen) 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). Nobody celebrates it, but the UK is The second largest source of services in the world. Nor is our service specialization behind our recent underperformance: on […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell 12% to 9% in the decade before the pandemic). Nobody celebrates it, but Britain is second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialization is not behind our recent underperformance: […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports has fallen) 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). Nobody celebrates it, but the UK is The second largest source of services in the world. Nor is our service specialization behind our recent underperformance: on […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] total exports) from 12% to 9% ten years before the pandemic).No one celebrates it, but the UK is second largest exporter Worldwide service. Our service expertise is not the reason for our recent underperformance: […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] exports fell from 12% to 9% in the pre-pandemic decade). No one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]

[…] one celebrates it, but the UK is the second largest exporter of services in the world. And our service specialism does not lie behind our recent […]