28 June 2019

Nicolo Tamberi is a Research Assistant in Economics for the UK Trade Policy Observatory. Dr Ingo Borchert is Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of Sussex and a fellow of the Observatory.

On Wednesday, the Department for International Trade (DIT) released its official statistics on inward foreign direct investments (FDI) for the financial year 2018-19.[1] As stated by the DIT, these data measure the inflow of ‘new investment, expansion, and mergers & acquisition’ projects, both publicly announced and not.

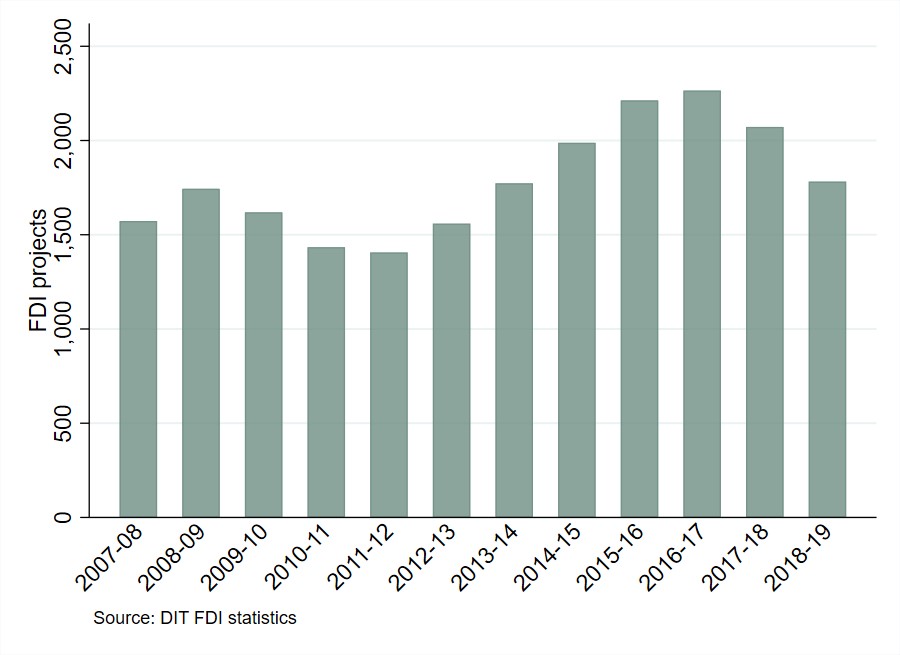

The number of FDI projects coming to the UK every year has been growing vigorously since the financial crisis ended in 2011/12. However, that trend ground to a halt in 2016/17, and for the past two years the number of incoming projects has shrunk (Figure 1). Compared to the previous year, FDI was down by 9% in 2017-18, and by another 14% in 2018-19. In comparison, last year’s fall even exceeds the one that occurred in 2010-11 during the global financial crisis.

The reversal of the trend coincides uncannily with the Brexit referendum, so we may just be seeing the chilling effect of Brexit uncertainty on the flow of inward investment to the UK. In fact, two studies had predicted such a decline in FDI as a consequence of the UK potentially exiting the Single Market. In the UKTPO Briefing Paper 23, we had estimated that the number of FDI projects would fall by about 16% in the period after the referendum result, relative to what might have happened in the absence of the vote. An LSE study came to similar conclusions employing a comparable methodology.

However, whilst DIT official statistics show the number of inward FDI projects in dramatic decline, the numbers are not directly comparable to the studies just mentioned. First, the DIT figures also include mergers & acquisitions projects. Second, the DIT figures show only the drop in FDI projects over time and so could reflect global investment conditions such as the slowing of economic growth or the hostile trade war atmosphere, as well as UK-specific factors like Brexit. By contrast, the LSE and UKTPO studies tried to isolate the impact of Brexit by looking at differences between the UK and a bundle of similar countries that resemble the UK but are not afflicted by uncertainty over leaving the EU. These differences notwithstanding, however, the way in which actual figures have begun to shape up is broadly consistent with the previous predictions (mentioned above) of the impact of Brexit.

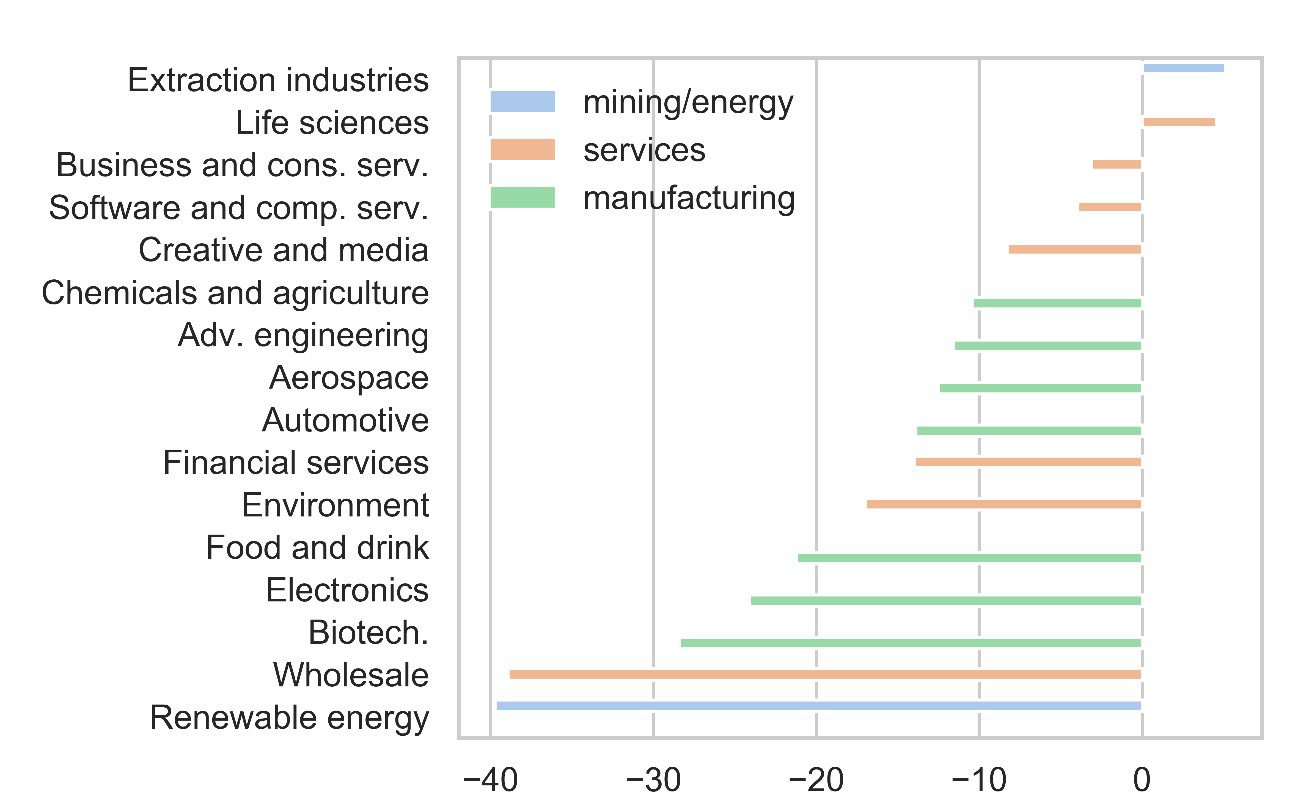

At the end of the day, though, whether the downturn is a consequence of Trumponomics or Brexit, it is simply bad news for the economy. It is not uniformly bad, though, since it appears that some large services sectors emerge as quite resilient amidst the general downturn.

The fact that financial services projects have been affected badly should not be surprising; however, two large and important services sectors—‘business and consumer services’ and ‘software and computer services,’ respectively—have barely been affected; they exhibit declines of 3% and 4% respectively. Between them, these two sectors account for 35% of all incoming projects. Creative and media services have also declined much less than the average. By contrast, most manufacturing sectors have seen their new FDI projects fall by a double-digit figure in the most recent data. The largest percentage declines are in wholesale and renewable energy, but these are relatively small sectors in terms of FDI and between them account for only 8% of 2018/19 total inflow of projects.

The relative resilience of services sectors in terms of inbound FDI flows bears some resemblance to the resilience of services trade flows, compared to goods trade. Over the period 2000-17, UK services exports grew at a higher rate and more smoothly than UK goods exports. Given these features, one would hope that trade and investment in services sectors receive the appropriate attention in UK trade policy formulation when the post-Brexit negotiations commence.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/department-for-international-trade-inward-investment-results-2018-to-2019

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

[…] How to Avoid a No-Deal Brexit → Politico: Experts propose alternative to Brexit backstop UKTPO: The Writing on the Wall: FDI Inflows and Brexit →‘No deal’ means ‘no deal’ →Brexit and global value chains: ‘No-deal’ is still […]