4 May 2022

Minako Morita-Jaeger is Policy Research Fellow at the UK Trade Policy Observatory and

Senior Research Fellow in International Trade in the Department of Economics, University of Sussex

The UK Government is aiming to secure the UK’s status as “a global hub” of digital trade, using Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) as well as digital economy agreements. Driven by the UK’s Indo-Pacific tilt strategy, the UK has been signing FTAs that include specific chapters/agreements on digital trade (such as with Australia, New Zealand, and Japan) and a digital economy agreement with Singapore.

While these agreements are expected to create economic opportunities, with a strong focus on free data flow and technological developments and innovation, they pose wider policy challenges such as the interoperability of data privacy law, cooperation in competition policy and security.

Since the UK is also in the process of joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), it is important to improve our understanding of the level of digital economy and digital governance in the Asia-Pacific. There is a digital divide and divergence of digital governance in the region, hence it would be sensible for the UK to take a comprehensive approach beyond FTAs/digital-only agreements to promote regulatory cooperation with Asia-Pacific countries.

Digital divide and divergence in digital governance in the Asia- Pacific

FTAs and digital trade agreements increasingly play a major role in shaping global digital trade governance especially as progress on digital trade at the World Trade Organization (WTO) is slow. Some Asia-Pacific countries, such as Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand, are pro-actively engaging in creating digital agreements, such as the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) between Singapore, New Zealand, and Chile and the Australia-Singapore bilateral Digital Economy Agreements.

If we consider the levels of digital competitiveness and digital governance in the Asia-Pacific region there are three characteristics that emerge when comparing across CPTPP members, CPTPP acceding countries (Taiwan, China and South Korea), other ASEAN countries (Indonesia, Thailand and Philippines), India and the US.

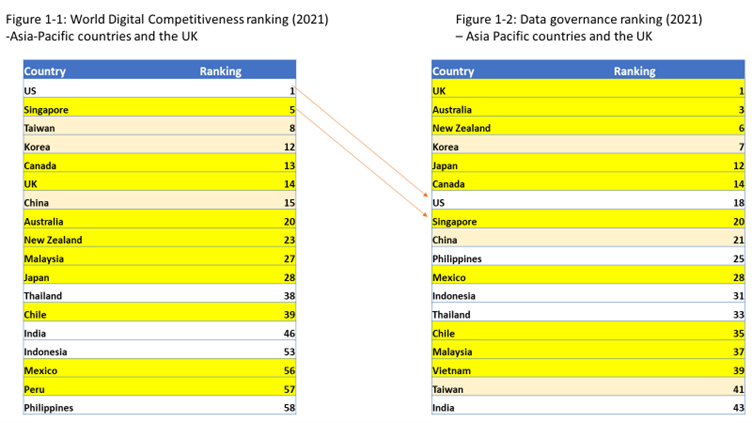

First, competitiveness in the digital economy varies across the Asia-Pacific. According to IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking (2021)[1], the USA is the most competitive data-driven country among selected 64 countries. Among CPTPP members, only Singapore, Canada) and Australia are ranked within the top 20 in the world. The three CPTPP acceding countries, Taiwan, Korea and China are also ranked within the top 20. CPTPP members that place in the middle of the board are: New Zealand, Malaysia and Japan. Low-performing includes Chile, Mexico and Peru (CPTPP countries); Thailand, Indonesia and the Philippines (non-CPTPP ASEAN countries); and India (Figure 1-1).

Source: Figure 1-1:“IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking 2021”, IMD World Competitiveness Center, p28. Figure 1-2 selected major Asia-Pacific countries from Figure 1-1. Figure 2-1: Global Data Governance Map

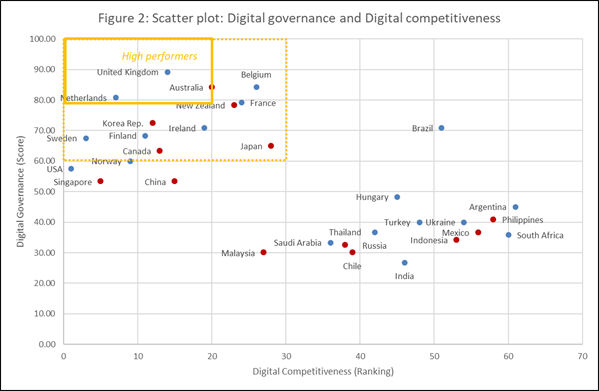

Second, countries with a high degree of digital competitiveness do not necessarily score highly on data governance. According to the Global Data Governance Map, which provides the metric that captures comprehensive data governance,[2] OECD countries show a high performance (Figure 2). Especially, European countries occupy the top performance group (UK, Germany, Netherlands, France, Ireland, Finland, and Sweden). In the Asia-Pacific, Australia, New Zealand, Korea, Japan and Canada belong to the high-performance group (Figure 1-2). As highlighted in yellow in Figure 2, these countries are good performers both in terms of digital competitiveness and digital governance.

The UK is one of the highest-ranked countries. Interestingly, the US and Singapore, the countries that show strong digital competitiveness, show relatively weak scores with regard to data governance. In the case of the US (18th), attributes of “Regulatory” (a legal regime around data’s types and/or uses), “Responsible” (the ethical, trust and human rights implications of data use and re-use) and “Participatory” (constituents’ participation to data governance) have a low score.[3] One example of a lack of regulatory attributes is that the US does not have a data privacy law at the federal level. As for Singapore (20th), the scores with regard to “Regulatory”, “Responsible” and “International” (international efforts to establish data governance rules and norms) are low. Although Singapore is active in creating digital agreements, its weakness lies in promoting ethical and trust frameworks such as providing a public sector data ethics framework and a trust framework for digital identity management.

Source: Digital governance: Global Data Governance Map. Digital competitiveness ranking :“IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking 2021”, IMD World Competitiveness Center.

Note: Since IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking does not provide scores, we use rankings. Thus, the scatter plot shows that countries in the higher left column are the best performers (high digital governance score with higher digital competitiveness) and that the lower right column are low-performing countries.

Third, countries with a low level of digital competitiveness are also low on digital governance. Among CPTPP members, Mexico, Chile, Malaysia and Vietnam belong to this group. ASEAN countries, (the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand) and India also show low performance (Figure 2). For example, Vietnam scored zero on “Responsible” performance since there are no legal frameworks that support ethical, trust and human rights aspects of data use and re-use. The performance of Chile, which is one of the signatories of the Digital Economy Partnership Agreement, shows high performance on the international attribute. However, it scored zero on “Responsible” and “Strategic” attributes. Like Vietnam, it lacks ethical, trust and human right related governance. Also, it lacks a long-term strategy or plan for how data should be used for society, such as a national data strategy, public administration data strategy, and AI strategy.

What does it mean for the UK?

It is worth noting that the UK is the best performer of data governance by attributes. The UK had high scores on every aspect of six attributes (“Structural”, “Regulatory”, “Participatory”, “International”, “Strategic”, and “Responsible”). It achieved a full score in “Strategic”, “Responsible” and “International attributes”.[4]

How, then, should the UK – surveyed as the world’s top performer of data governance – promote regulatory cooperation in digital trade with Asia-Pacific countries? There are two things to be noted. First, it would be in the UK’s interest to advocate that Asia-Pacific countries promote a regulatory regime that can enhance trust. Like Singapore, many Asia-pacific countries are relatively weak in promoting legal frameworks in recognising and mitigating risks and potential harms of a data-driven economy[5] and in considering the implications of data-driven changes on trust, equity and human rights into policy.[6] The UK could encourage its trade partners to strengthen these policy areas.

Second, especially for developing countries – that are left behind both in terms of digital governance and digital competitiveness – the UK could assist to level up digital governance. Although the e-commerce chapter in the CPTPP promotes free cross-border data flow, a digital divide and divergence of digital governance exist among CPTPP members. Also, non-CPTPP members, such as ASEAN countries and India, with which the UK is seeking to extend economic relations, are behind in digital governance. Technical cooperation and capacity building to enhance legal frameworks and institution building could be a way to improve digital governance in the Asia-Pacific and the UK could play a role in these areas.

A comprehensive multi-stakeholder approach beyond FTAs/digital-only agreements could be seen as a way to enhance digital trust in the region for long-term social and economic prosperity. The UK could make use of its experience and knowledge to widely improve digital governance and promote regulatory cooperation in the Asia-Pacific.

Footnotes

[1] IMD World Digital Competitiveness Ranking (2021) surveyed 64 countries. Among CPTPP members, Vietnam and Brunei are not included. The Ranking defines digital competitiveness into three factors and each factor is further divided into 3-sub-factors: “Knowledge” (sub-factors: talent, training and education, scientific concentration), “Technology” (subfactors: Regulatory framework, capital, technological framework), and “Future readiness” (sub-factors: adaptive attitudes, business agility and IT integration). See methodology in detail: World Digital Competitiveness Rankings – IMD. IMF World Digital Competitiveness Ranking does not provide scores.

[2] The Global Data Governance Map surveyed data governance of 51 countries plus the EU both at the national and international levels using six attributes: “Structural”, “Regulatory”, “Participatory”, “International”, “Strategic”, and “Responsible” and subdivided 26 indicators. Among CPTP members, Peru and Brunei are not included. See the methodology in detail in Aaronson, S. et all (2020). DataGovHub Paradigm for a Comprehensive Approach to Data Governance Year 1 Report.

[3] Sub-categories (26 indicators) of six attributes are as follows: “Strategic”: national data strategy, public administration data strategy, national guidelines for private sector data sharing, and AI strategy. “Regulatory”: law for the protection of personal data, open data law for the proactive release of government information by default, freedom of information act ensuring citizens can access government documents, right to be protected from automated decision-making, and right to data portability. “Responsible”: digital charter, public sector data ethics framework or guidance, AI ethics framework, and trust framework for digital identity management. “Structural”: data protection body, open data portal, open data body, public sector data governance body, and international data affairs body. “Participatory”: public consultation on personal data protection, public consultation on public data, expert advisory body on ethics and expert advisory body on data-driven technical change and its impact on society. “International”: Convention 108, open government Partnership, OECD AI Principles, and trade agreements with binding provisions on cross-border data flows. See the explanation in detail at Global Data Governance Map.

[4] “Participatory” is relatively weak among the six attributes. For example, the UK is not well performing with regard to expert advisory body on data-driven technical change and its impact on society (DataGovHub – The United Kingdom (letsnod.com)).

[5] For example, protection of personal data, freedom of information act to ensure citizens’ access to government documents, and right to be protected from decision-making.

[6] For example, digital charter, AI ethics framework, and trust framework for digital identity management.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

[…] trust,” said Minako Morita-Jaeger, Policy Research Fellow at the UK Trade Policy Observatory, in a UKTPO blog posted on Wednesday (4 […]