19 May 2023

Michael Gasiorek is Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy. He is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Nicolo Tamberi is Research Officer in Economics at the University of Sussex and Fellow of UKTPO.

Michael Gasiorek is Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy. He is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Nicolo Tamberi is Research Officer in Economics at the University of Sussex and Fellow of UKTPO.

Earlier this week Vauxhall announced it may withdraw from producing electric vehicles in the UK owing to difficulties from meeting ‘rules of origin’ on EU exports. The car manufacturer called for a revision to the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) between the EU and then UK, notably regarding rules of origin (ROOs). Ford and Jaguar Land-Rover have also warned of the difficulties and called for a revision to the TCA and German producers have also expressed concerns about the meeting these ROOs.

The issue is the following: The Trade and Cooperation Agreement with the EU allows for tariff-free trade between the EU and the UK, providing that the goods being exported originate (i.e. are sufficiently produced) in each country. There are different rules regarding batteries and cars. Some of the key elements are in relation to the maximum value of non-originating materials:

The current struggle to meet the ROOS for electrical vehicles is in part due to the need to import the batteries for those vehicles, which typically constitute 30-40% of the cost of an electric car, and because of the rise in raw materials costs. If the ROOs cannot be met, then a tariff of 10% would be levied on the exports of those cars from the UK and the EU, and vice versa. Note that, paradoxically, tariffs would be levied on electric vehicles, while less environmentally friendly petrol/diesel vehicles would remain exempt.

In the short term there is an obvious remedy to this problem: extend the deadlines for the current, and more generous, ROOs regime. Importantly, this would not require any renegotiation of the TCA. Article 68 of Chapter 2 (Rules of Origin) states that “The Partnership Council may amend this Chapter and its Annexes”. Similarly, Article 519 states that “The Partnership Council may: (a) adopt decisions to amend: (i) Chapter 2 of Title I of Heading one of Part two and its Annexes, in accordance with Article 68”.

Unlike so many Brexit-related issues, this problem can be relatively easily overcome if there is political goodwill from both the UK and the EU. As Kemi Badenoch, the Trade and Business Secretary acknowledged in Parliament yesterday, the difficulties in meeting the ROOs apply to both sides. One might hope the economic concerns and political incentives may be strong enough for this to be resolved. There is of course the possibility that the EU perceives the issue to be more important for the UK and may ask for other concessions in return.

If a resolution is not found, there will be material consequences for the UK car industry. It is worth also considering how important this is for the UK. Overall, cars (technically, HS8703 in the trade classification) accounted for over 8% of UK exports in 2022, and over 6% of imports. Out of over 1,200 products defined at this (four-digit) level, cars are the UK’s 5th most significant export and its 2nd most important import. From the total UK car exports and imports in 2021, the share of electric / hybrid cars was 36% and 38% respectively.[1]

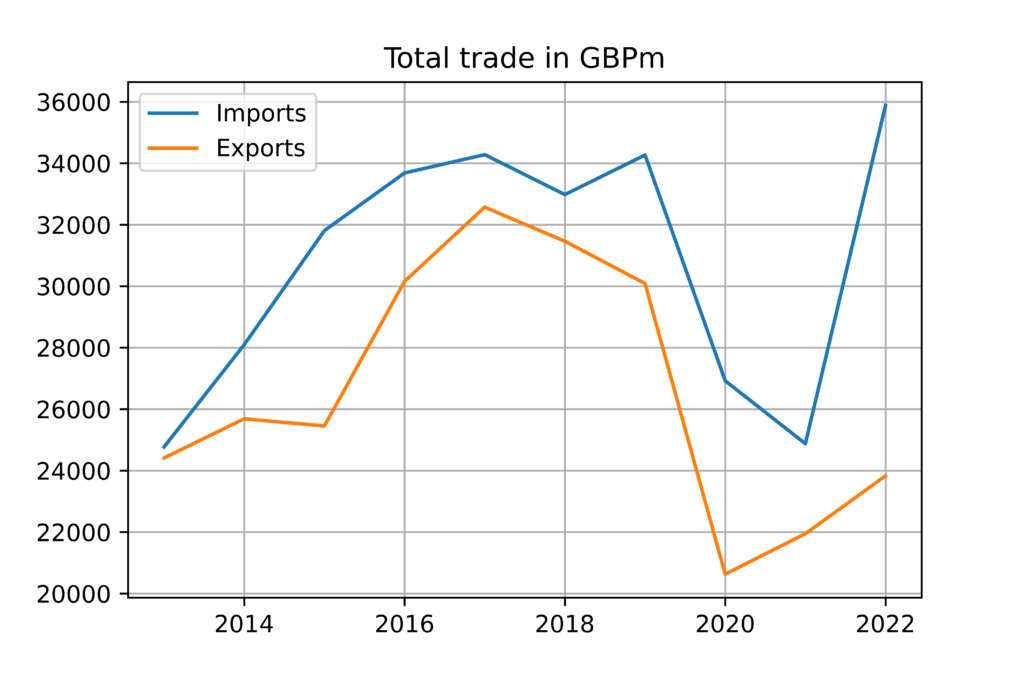

Over the last 10 years, an average of 86% of UK imports came from the EU, while 38% of UK exports were sold to the EU. Overall, as the graph below shows, UK exports have significantly declined since 2017, while the share of exports to the EU declined from 42% in 2016 to below 36% in 2022. Up to 2021, imports also declined substantially, with a rise in 2022 – although this needs to be interpreted carefully since there were concurrent changes in the recording of UK imports. The share of imports from the EU declined from over 90% to just over 76%. Our formal (econometric) analysis suggests that imports of cars from the EU (relative to non-EU sources since the introduction of the TCA) were down by nearly 60% by the end of 2021, and by close to double that by the end of 2022. In contrast, while exports to the EU appear to have declined by over 5% by the end of 2021, and nearly 12% by the end of 2022, these results are not statistically significant.

In short: both the car industry and the EU market matter to the UK. Recent years have already seen substantial changes in trade, both overall and with the EU. If producers such as Vauxhall relocate, this could indeed have substantial repercussions. There is a strong case for, at a minimum, extending the existing arrangement, which is possible within the existing framework between the UK and the EU.

Where others (such as the US with the Inflation Reduction Act) are actively intervening to try and ensure domestic battery resilience, rightly or wrongly, there is little evidence of such an approach in the UK. This does not bode well for the longer-term future of the car industry in the UK, nor its move towards a lower-carbon world. Ensuring that, at least, supply chains with the EU are maintained, even in the interim, would be a key first step.

[1] EV/hybrid vehicles are those described as HS products 870340, 870350, 870360, 873070, 870380.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

[…] UK automotive industry may have declined from its 1970s peak but it is still an important part of our economy and employs 800,000 people. In 2022, cars were the UK’s fifth most important export and its […]