June 28, 2024 Anupama Sen is a Research Assistant in International Trade (Economics) at the UKTPO.

Anupama Sen is a Research Assistant in International Trade (Economics) at the UKTPO.

For nearly a decade, China has been the linchpin of global supply chains, thanks to its competitive labour costs and vast manufacturing prowess, earning it a moniker as the ‘factory of the world’. China’s strong manufacturing position extends to the automotive industry. Against that backdrop, starting on 4 July 2024, the EU will implement tariffs, in the form of countervailing duties (CVDs) ranging from 17% to 38%, on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs). These duties on Chinese EV imports will be on top of an existing 10% duty, thereby reaching a peak of 48%. The decision to levy further duties follows an investigation by the European Commission launched in October to investigate Chinese subsidies distorting EV prices and posing unfair competition risks to European carmakers. Thus, the tariffs are applied on a company-specific basis, tailored to the level of subsidies allegedly received by Chinese firms.

The EU’s tariffs on Chinese EVs could be seen as a strategic move aimed at reducing its dependency on China in this sector whilst at the same time stimulating domestic EV production. While some may view this policy as protectionist or neo-mercantilist, it could alternatively be seen as a prudent industrial strategy to foster economic resilience for the EU and to create a level playing field in the global market for EVs. This blog explores the necessity for such a strategy, supported by data illustrating the EU’s growing reliance on Chinese EV imports.

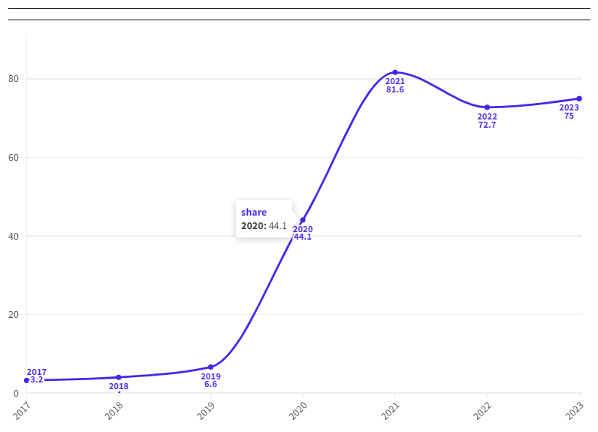

Imports of Chinese produced EVs into the EU market have increased significantly over recent years. Table 1 presents the import values for the car industry and electric vehicles (EVs) from 2017 to 2023, while Figure 1 shows the share of EVs within the total car industry imports. The share of EV’s in total car imports from China rose substantially from 3.2% in 2017 to 81.6% in 2021, with a slight rebound thereafter. While it is difficult to pin down any single specific factor that led to this surge in EV imports in 2021, by then China’s EV industry had grown substantially. This was in part due to substantial state subsidies that enabled manufacturers to offer EVs at competitive prices. Additionally, the EU’s commitment to green energy, including incentives from the 2019 Green Deal, had made the market more receptive to EV imports. Lower trade barriers for Chinese EVs in the EU compared to regions like the U.S. also facilitated this surge. However, EU imports from China have been rising in absolute terms throughout the entire period, in both EVs and non-EVs.

|

Year |

Car Industry (billion USD) HS 8703 |

Electric Vehicles (billion USD, HS 870380) |

|

2017 |

0.46 |

0.01 |

|

2018 |

0.61 |

0.02 |

|

2019 |

1.02 |

0.07 |

|

2020 |

2.06 |

0.91 |

|

2021 |

7.03 |

5.74 |

|

2022 |

9.94 |

7.23 |

|

2023 |

13.96 |

10.47 |

Source: UN Comtrade

Notes: Figures are in billion USD. HS code 870380 refers to: Motor cars and other motor vehicles principally designed for the transport of <10 persons, incl. station wagons and racing cars, with only electric motor for propulsion (excl. vehicles for travelling on snow and other specially designed vehicles of subheading 8703.10).

Source: Author’s Calculation on Import data from 2017 to 2021 using UN Comtrade

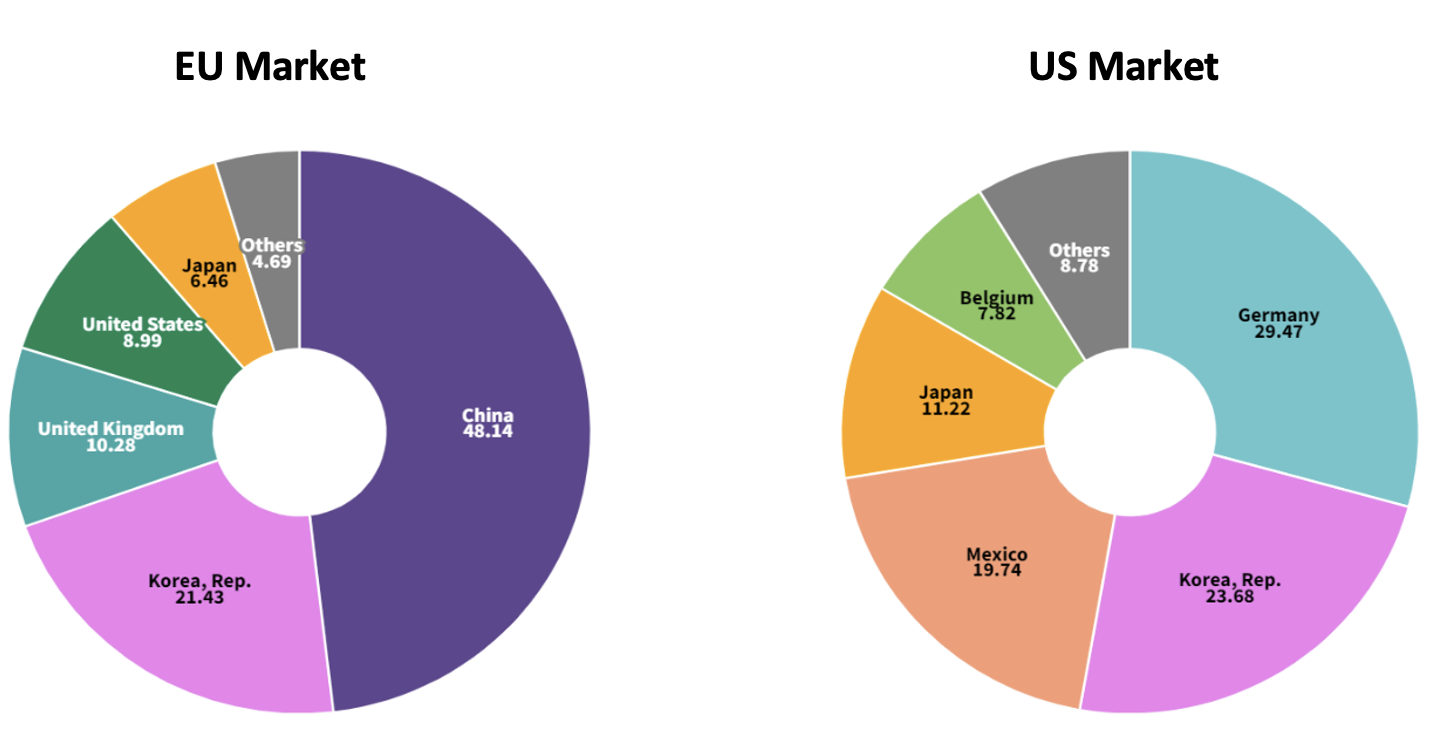

Whereas the EU has implemented tariffs on Chinese EVs in the face of a huge surge in imports, the United States has imposed even higher tariffs of up to 100% on Chinese EV imports despite minimal penetration of these vehicles in its market. Unlike the EU with its heavy reliance on China, the US has diversified its EV supply chain primarily through suppliers in Germany, Korea, and Mexico. This difference underscores how the EU’s approach is potentially consistent with addressing concerns about economic vulnerabilities and promoting local industry growth. In contrast, the US strategy focuses more on safeguarding its existing supply chain diversification.

Figure 2 shows the largest suppliers of EVs to the EU and US markets, respectively. We can observe how heavily reliant the EU is on China as the largest supplier of EVs by a wide margin, whereas the US has been able to diversify its supply chain sufficiently among other exporters.

Source: Author’s Calculation from UN Comtrade Data

Beyond the economic implications, China has complained that the EU duties contravene WTO rules. The WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement) provides the legal framework for these actions, allowing member countries to impose countervailing duties on subsidized imports harming domestic industries. While differentiating duties by firm is common in anti-dumping cases, it is less familiar in the context of subsidies. This differentiation might initially raise concerns about discrimination. Article 15(2) of Regulation (EU) 2016/1037 allows the EU to impose firm-specific countervailing duties. The SCM Agreement’s silence on this practice implies its likely permissibility due to the absence of an express prohibition.

Moreover, the EU’s regulation includes a separate procedure for calculating duties in cases of non-cooperation, potentially resulting in higher tariffs for such firms. Nevertheless, the basis for selecting specific Chinese companies under investigation remains unclear. Chinese firms receive various forms of support, including preferential interest rates, directed credit, tax credits, and cross-subsidies. The methodology for calculating tariffs has only been circulated to the sampled firms thus far. Until the EU publishes its methodology, it is difficult to fully assess the legal validity of the EU’s differentiated tariffs and how subsidies for each firm have been accounted for, as well as the injury to the EU industry caused by each firm.

The EU’s tariffs on Chinese EVs will have varied economic repercussions. They may serve as a catalyst for Chinese manufacturers to relocate production to the EU. For instance, Chinese carmaker BYD has established EV plants in Hungary, and Geely has shifted production to Belgium. This shift has the potential to attract investment, bolster local manufacturing, stimulate job creation, and enhance EU technological capabilities.

However, the immediate consequence of higher tariffs could be increased costs for consumers as part of the tariff rise will most likely be passed on to them. In addition, more protection for EU producers might shift their focus away from innovating and seeking efficiency gains. Finally, the tariffs may strain EU-China trade relations and prompt retaliatory measures.

Imposing tariffs on Chinese EVs may also jeopardize the EU’s ambitious climate goals, as outlined in the European Green Deal. Higher tariffs are almost surely set to slow down EV adoption rates in the EU, delaying the transition away from fossil fuel-powered vehicles and hindering progress towards achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Additionally, efforts to boost local EV production in response to tariffs may temporarily raise CO2 emissions during manufacturing, particularly in energy-intensive battery production. Striking a balance between trade policies and environmental objectives is crucial to ensure that measures such as CVDs support rather than hinder the EU’s carbonization progress.

As the US and EU pivot away from heavy reliance on Chinese manufacturing, they are integrating ASEAN nations (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) into their supply networks. These efforts are bolstered by frameworks such as the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)[1]. This strategic shift underscores the imperative of diversifying supply chains to enhance economic resilience amidst global uncertainties.

In this recalibration, cultivating strategic partnerships—often termed friendshoring—takes on critical significance. These alliances aim to deepen economic collaboration while mitigating risks associated with overreliance on single suppliers. As part of such initiatives, the EU may aim at strategically diversifying its EV supply chain by investing in economies such as Mexico, Japan, and South Korea, thereby enhancing supply chain resilience and reducing dependency on China. India, with its burgeoning EV market, represents a significant opportunity. Notably, in 2023, India surpassed China in three-wheeler EV sales, underscoring its potential as a key player in the global EV industry[2].

The EU’s impending tariff hike on Chinese EVs presents a complex challenge touching on economic, environmental, and geopolitical dimensions. While aimed at protecting European industries from unfair competition, these measures may strain EU-China relations and potentially undermine the EU’s climate goals. Balancing the need to diversify supply chains with environmental goals and political costs is crucial to mitigate risks and ensure sustainable economic growth.

[1] Neither the EU nor the US are part of CPTPP, even though the agreement is shaped on the provisions negotiated for the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP). This latter was heavily influenced by the US, although it withdrew from it in 2017 and CPTPP came into effect between 11 signatories in 2018. The UK signed an accession protocol in 2023.

[2] https://www.cnbc.com/2024/04/26/india-says-new-ev-policy-will-open-up-market-to-global-players-.html

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 28th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

June 25 2024

June 25 2024

Sahana Suraj is a UKTPO Research Fellow in International Trade.

With less than two weeks until the United Kingdom elects its 59th parliament, campaigning efforts by contesting political parties intensified with the recent publication of party manifestos.[1] The UK is the fourth largest exporter of goods and services, so it is particularly important to shine light on the next government’s stance for developing a robust trade policy that maximises the benefits of trade consistent with domestic policy objectives.

While clearly there is a degree of overlap, the approaches to trade (policy) by the main parties—Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats, Green Party, Reform UK—can be broadly categorised into three different groups.

One group, consisting of the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats, appears to align trade policy with industrial strategy. Concerned with building a resilient and secure economic future, their proposed course of action aims at capitalising on the UK’s existing economic strengths, including in services trade. This approach entails a focus on the depth and quality of agreements, forging strategic partnerships to create a pro-business and pro-innovation environment, and making trade more accessible.

This orientation to trade policy can be characterised as going beyond a conventional focus on Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). Labour, for instance, also recognises the importance of Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) and standalone agreements to promote services trade and digital trade. Agreements of this nature can have strong trade promotion effects and can be effective in reducing non-tariff barriers to trade. The Liberal Democrats have stressed the importance of human rights, labour rights, and environmental standards while negotiating trade deals. This indicates their commitment to using trade policy to achieve benefits in other areas of public policy. They propose renegotiating existing trade agreements with Australia and New Zealand to achieve more favourable outcomes for the UK in health, the environment, and in animal welfare.

Both parties are focused on promoting deeper cooperation in trade policy by expanding markets for British exporters and deepening trade partnerships. Labour also endorse the ongoing FTA negotiations with India and are open to negotiating agreements with the United States and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Moreover, they recognise the importance of African economies and multilateral institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Another group consists of manifestos whose approach to trade policy derives from their commitment to sovereignty above all. This includes the Conservatives and to a lesser extent Reform UK. They focus on the imperative for the UK to independently dictate its course on all trade policy matters, as well as protecting the UK’s internal market. The Conservatives propose heavy reliance on FTAs to extend ties to Switzerland, the Middle East (GCC, Israel), Asia (India, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia) and the United States, the rationale being an expansion of trading relationships post-Brexit. The aim of these agreements is largely to increase cooperation in trade, technology, and defence that will eventually allow the UK to become the largest defence exporter in Europe by 2030. These strategies exemplify their strong emphasis on linking trade policy with economic security.

As part of the focus on sovereignty, the Conservatives and Reform UK both assign importance to agriculture. Ending UK quotas for EU fishers, creating opportunities for the domestic food and drink industry, and recognising the importance of farmers while negotiating FTAs are issues raised by the parties. There are also detailed plans to promote intra-UK trade. While Reform UK proposes a rather radical approach by abandoning the Windsor Framework, the Conservatives recommend the establishment of an Intertrade body to promote Scottish exports and partnerships with British Overseas Territories.

Lastly, the Green Party’s stance on trade policy incorporates elements found in the preceding two groups with policies that encourage trade agreements to take account of worker’s rights, consumer rights, animal protection, and environmental standards, and a traditional focus on agriculture. They advocate the ending of what the party perceives as unfair deals related to food and agriculture and rather place emphasis on encouraging domestic food production.

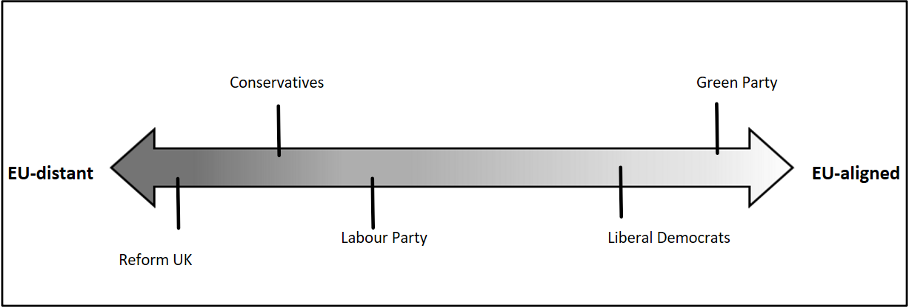

The question of the UK’s future relations with Europe is arguably of central importance from a trade perspective. On this aspect, the parties exhibit much greater divergence between each other, than their general stance on trade. Each of the parties proposes varying levels of engagement with the European Union as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Level of closeness to the EU as proposed by the parties’ manifestos.

Both main parties—the Conservatives and Labour—are against Britain’s return to the European Union. However, they differ on future trade relations with Europe. Labour advocates closer ties with the EU and wants to take advantage of Britain’s geographical proximity to the region. It intends to negotiate a mutual recognition agreement with European counterparts on professional qualifications and services exports. Labour is also in agreement with the EU’s approach to transition to Net Zero by adopting a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and they aim at negotiating a veterinary agreement with the EU to reduce the burden of border checks.

In contrast, the Conservatives place legal sovereignty above other interests and accept a gradually growing regulatory distance from the EU as a result. They are keen to repeal EU laws that have been transposed into UK law since Brexit and ensure that the EU’s commitments are met under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA). They intend to dub the UK as the largest net exporter of electricity and implement a new carbon import pricing mechanism by 2027.

The position towards the EU of the other parties—Green, Reform, and Liberal Democrats—fall at either end of the spectrum. While Reform staunchly advocates for a complete renegotiation of the TCA and seeks to distance themselves completely from Europe, the Green Party and Liberal Democrats propose an eventual re-integration into the European Union. The Liberal Democrats especially want to align the UK’s and EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) and also align the UK’s food standards with that of Europe.

From the outset, trade policy does seem to be on the agenda of contesting parties, albeit still considered in conjunction with Brexit. That being said, there is a significant degree of uncertainty attached to the UK’s future trade policy, as the main parties present starkly opposite proposals on EU relations. And yet, the UK is an open economy that relies on international trade for economic prosperity and jobs. Therefore, the next government’s approach to trade policy and trade governance will matter a great deal, and the more clarity voters have over the parties’ intentions, the better.

[1] Party manifestos can be accessed by visiting the following links:

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 25th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

18 June 2024

18 June 2024

Alasdair Smith is a UKTPO Research Fellow, a researcher within the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP), Emeritus Professor of Economics and Former Vice-Chancellor at the University of Sussex.

The 2019 General Election focused on the one issue of Brexit, and Boris Johnson’s victory enabled the UK to leave the EU. The evidence analysed by UKTPO and many others since then has confirmed the general expectation among expert economists at the time that Brexit would have negative economic effects. And recent opinion poll evidence is that a majority of voters think Brexit was a mistake.

To say that Brexit was a mistake does not imply it could or should be simply reversed. Yet, it is reasonable to expect the political parties to address the issue in their current election campaigns.

The Labour Party’s ambition for the future EU-UK relationship is set out in two paragraphs in their manifesto published on 13 June:

“With Labour, Britain will stay outside of the EU. But to seize the opportunities ahead, we must make Brexit work. We will reset the relationship and seek to deepen ties with our European friends, neighbours and allies. That does not mean reopening the divisions of the past. There will be no return to the single market, the customs union, or freedom of movement.

Instead, Labour will work to improve the UK’s trade and investment relationship with the EU, by tearing down unnecessary [my emphasis] barriers to trade. We will seek to negotiate a veterinary agreement to prevent unnecessary border checks and help tackle the cost of food; will help our touring artists; and secure a mutual recognition agreement for professional qualifications to help open up markets for UK service exporters.”

A firm commitment to stay out of the EU for the next Parliament is surely wise. The UK-EU relationship has been bruised by the experience of the last 8 years. Rebuilding the relationship will take time and patience, and the opportunity to solidify the long-term relationship lies some way in the future. The incoming government faces formidable challenges in many areas and even a long-term plan to rejoin the EU would be a diversion from more immediate priorities.

Since there is no plan to rejoin, it follows that a new government must indeed seek to “make Brexit work”. It’s also right to aim for the removal of any unnecessary border checks and other barriers to trade that have damaged the UK economy.

This is a more positive and less dogmatic approach to the UK-EU relationship than the Conservative manifesto whose main concern is to rule out “dynamic alignment” to EU rules and “submission to the CJEU [the Court of Justice of the EU]”.

Dynamic alignment means sticking to EU rules even when they change. There’ s a strong case for dynamic alignment in many areas, to create a climate of regulatory predictability in place of the regulatory uncertainty and instability of recent years. In any case, firms have to satisfy EU regulations for products they sell in the EU. In many important sectors of the economy (like chemicals and motor vehicles) that means virtually all their production has to meet EU requirements, so separate UK regulations are a deadweight cost.

The Labour manifesto’s red lines are clearly drawn: “no return to the single market, the customs union, or freedom of movement”. The political pressure for such clear lines is understandable. However, they will constrain the objective of reducing border checks and other barriers to trade.

The European single market (which encompasses some non-EU countries like Norway) is the regulatory framework which removes barriers to trade within Europe. Members of the single market adopt common regulations, common processes for assessing conformity with these regulations, and a common legal framework under the umbrella of the CJEU. Members of the customs union similarly have a common policy towards goods imported from non-member countries. Checks on trade between EU countries are unnecessary.

However, if the UK remains outside the single market and the customs union, checks on UK exports to the EU are necessary to make sure that EU rules are satisfied. It’s not enough for UK producers to satisfy EU rules – their products still need to be checked for conformity. However much trust and goodwill are built up with our EU partners and no matter how much alignment there is with EU rules, the scope for removing “unnecessary” barriers to UK-EU trade may be frustratingly limited in practice.

The main political barrier to UK membership of the single market is, of course, the additional single market requirement for the free movement of labour. But post-Brexit restrictions on labour mobility between the EU and the UK has had adverse effects in many important UK sectors: including business services, agriculture, hospitality, social care, and the creative industries.

It’s understandable that the Labour manifesto rules out free movement, but notable that it is silent on the recent EU offer on youth mobility: proposals which emphatically do not imply freedom of movement (not least because they involve visa controls). These proposals would restore to young Europeans in the UK and the EU some of what they lost as a result of Brexit, and would also help address some of the problems of the sectors most affected by Brexit. Surely an incoming government should take a more positive approach to the EU offer.

Opinion poll evidence is that a clear majority of the UK electorate favour a return to EU-UK freedom of movement. A new government may find the political constraints changing quite quickly, so that rejoining the single market becomes thinkable.

A manifesto commitment not to rejoin the single market applies to the next Parliament but doesn’t stop the government from preparing to rejoin in the following Parliament. The path to re-entering the single market would in any case be a long one, probably via the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) into the European Economic Area (the EEA). This path requires preparation and negotiation.

That preparation should include addressing the fact that the single market requires free movement of labour not free movement of citizens. The UK could develop rules for a regime in which EEA citizens are not unconditionally free to come to the UK but are free to relocate to the UK (with their families) in order to work.

The Liberal Democrat manifesto, in contrast to the Labour manifesto’s red lines, makes a positive commitment to rejoining the single market:

“Finally, once ties of trust and friendship have been renewed, and the damage the Conservatives have caused to trade between the UK and EU has begun to be repaired, we would aim to place the UK-EU relationship on a more formal and stable footing by seeking to join the Single Market.”

Realistically, the timetable suggested by these words could well extend beyond the 4-5 years of the next Parliament. In this case, the difference between the Labour and LibDem manifestos may be presentational, rather than real. The single market issue will not go away, even if it cannot be settled before another general election at which a proposal to rejoin the single market could be put to the electorate.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 18th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised