June 25 2024

June 25 2024

Sahana Suraj is a UKTPO Research Fellow in International Trade.

With less than two weeks until the United Kingdom elects its 59th parliament, campaigning efforts by contesting political parties intensified with the recent publication of party manifestos.[1] The UK is the fourth largest exporter of goods and services, so it is particularly important to shine light on the next government’s stance for developing a robust trade policy that maximises the benefits of trade consistent with domestic policy objectives.

While clearly there is a degree of overlap, the approaches to trade (policy) by the main parties—Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats, Green Party, Reform UK—can be broadly categorised into three different groups.

One group, consisting of the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats, appears to align trade policy with industrial strategy. Concerned with building a resilient and secure economic future, their proposed course of action aims at capitalising on the UK’s existing economic strengths, including in services trade. This approach entails a focus on the depth and quality of agreements, forging strategic partnerships to create a pro-business and pro-innovation environment, and making trade more accessible.

This orientation to trade policy can be characterised as going beyond a conventional focus on Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). Labour, for instance, also recognises the importance of Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) and standalone agreements to promote services trade and digital trade. Agreements of this nature can have strong trade promotion effects and can be effective in reducing non-tariff barriers to trade. The Liberal Democrats have stressed the importance of human rights, labour rights, and environmental standards while negotiating trade deals. This indicates their commitment to using trade policy to achieve benefits in other areas of public policy. They propose renegotiating existing trade agreements with Australia and New Zealand to achieve more favourable outcomes for the UK in health, the environment, and in animal welfare.

Both parties are focused on promoting deeper cooperation in trade policy by expanding markets for British exporters and deepening trade partnerships. Labour also endorse the ongoing FTA negotiations with India and are open to negotiating agreements with the United States and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Moreover, they recognise the importance of African economies and multilateral institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Another group consists of manifestos whose approach to trade policy derives from their commitment to sovereignty above all. This includes the Conservatives and to a lesser extent Reform UK. They focus on the imperative for the UK to independently dictate its course on all trade policy matters, as well as protecting the UK’s internal market. The Conservatives propose heavy reliance on FTAs to extend ties to Switzerland, the Middle East (GCC, Israel), Asia (India, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia) and the United States, the rationale being an expansion of trading relationships post-Brexit. The aim of these agreements is largely to increase cooperation in trade, technology, and defence that will eventually allow the UK to become the largest defence exporter in Europe by 2030. These strategies exemplify their strong emphasis on linking trade policy with economic security.

As part of the focus on sovereignty, the Conservatives and Reform UK both assign importance to agriculture. Ending UK quotas for EU fishers, creating opportunities for the domestic food and drink industry, and recognising the importance of farmers while negotiating FTAs are issues raised by the parties. There are also detailed plans to promote intra-UK trade. While Reform UK proposes a rather radical approach by abandoning the Windsor Framework, the Conservatives recommend the establishment of an Intertrade body to promote Scottish exports and partnerships with British Overseas Territories.

Lastly, the Green Party’s stance on trade policy incorporates elements found in the preceding two groups with policies that encourage trade agreements to take account of worker’s rights, consumer rights, animal protection, and environmental standards, and a traditional focus on agriculture. They advocate the ending of what the party perceives as unfair deals related to food and agriculture and rather place emphasis on encouraging domestic food production.

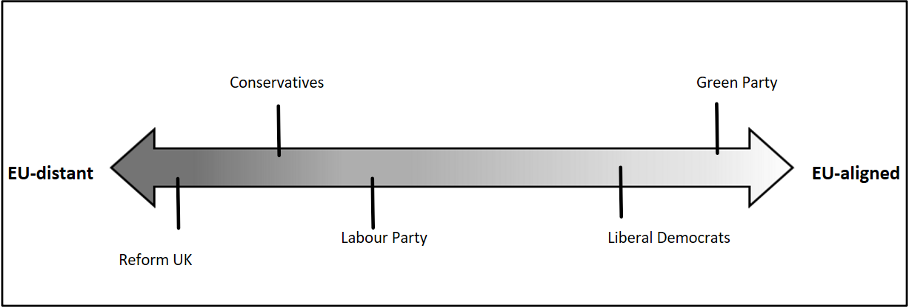

The question of the UK’s future relations with Europe is arguably of central importance from a trade perspective. On this aspect, the parties exhibit much greater divergence between each other, than their general stance on trade. Each of the parties proposes varying levels of engagement with the European Union as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Level of closeness to the EU as proposed by the parties’ manifestos.

Both main parties—the Conservatives and Labour—are against Britain’s return to the European Union. However, they differ on future trade relations with Europe. Labour advocates closer ties with the EU and wants to take advantage of Britain’s geographical proximity to the region. It intends to negotiate a mutual recognition agreement with European counterparts on professional qualifications and services exports. Labour is also in agreement with the EU’s approach to transition to Net Zero by adopting a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and they aim at negotiating a veterinary agreement with the EU to reduce the burden of border checks.

In contrast, the Conservatives place legal sovereignty above other interests and accept a gradually growing regulatory distance from the EU as a result. They are keen to repeal EU laws that have been transposed into UK law since Brexit and ensure that the EU’s commitments are met under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA). They intend to dub the UK as the largest net exporter of electricity and implement a new carbon import pricing mechanism by 2027.

The position towards the EU of the other parties—Green, Reform, and Liberal Democrats—fall at either end of the spectrum. While Reform staunchly advocates for a complete renegotiation of the TCA and seeks to distance themselves completely from Europe, the Green Party and Liberal Democrats propose an eventual re-integration into the European Union. The Liberal Democrats especially want to align the UK’s and EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) and also align the UK’s food standards with that of Europe.

From the outset, trade policy does seem to be on the agenda of contesting parties, albeit still considered in conjunction with Brexit. That being said, there is a significant degree of uncertainty attached to the UK’s future trade policy, as the main parties present starkly opposite proposals on EU relations. And yet, the UK is an open economy that relies on international trade for economic prosperity and jobs. Therefore, the next government’s approach to trade policy and trade governance will matter a great deal, and the more clarity voters have over the parties’ intentions, the better.

[1] Party manifestos can be accessed by visiting the following links:

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.