23 July 2024

23 July 2024

Minako Morita-Jaeger is Policy Research Fellow at the UK Trade Policy Observatory, a researcher within the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and Senior Research Fellow in International Trade in the Department of Economics, University of Sussex. She currently focuses on analysing UK trade policy and its economic and social impacts.

The UK is a services economy which accounts for 81% of output (Gross Value Added) and 83% of employment.UK services exports (£470 billion in 2023) are the world’s second largest after the US and 75% of its services exports are digitally delivered. The UK is ranked as world-leading in terms of data governance. Under the new Labour government, it is time to take the initiative on data flow governance at the global stage to achieve a sustainable and accountable digital environment. With the set back in the US negotiations on free data flows at the WTO, the UK can take the initiative to collaborate with the EU and Japan.

The EU-Japan EPA, which entered into force in 2019, lacked provisions on free data flows and personal data protection. This has now been addressed with the signing of the new protocol on 31 January this year which is incorporated into the EU-Japan EPA. The new EU-Japan protocol can be seen as game changers. First, they strike a balance between free data flows and legitimate public policy objectives. Under Article 8.81, measures that prohibit or restrict cross-border data flows, such as localisation requirements of computing facilities or network elements, are restricted. These provisions are similar to the existing digital trade provisions under FTAs/digital trade agreements led by the Asia-Pacific countries, such as the CPTPP.

Yet a significant difference with the Asia-Pacific style FTAs is the scope and definition of “legitimate public policy objective” (Art. 8.81.3 and its footnotes). The new protocol reflects the EU’s approach under the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) which provides more detail compared to the Asia-Pacific led digital trade agreements.

Another striking difference is that personal data protection is set as a fundamental right. The provisions regarding cross-border data transfers go together with the new provisions regarding protection of personal data (Art. 8.82). The clause is comprehensive and could be seen as the highest standard among existing digital trade agreements, including the EU-UK TCA. It underlines the importance of maintaining high standards of personal data protection to ensure trust in the digital economy and to develop digital trade. Such deep commitments between the EU and Japan were enabled by ongoing policy dialogues, including the EU-Japan Digital Partnership Council.

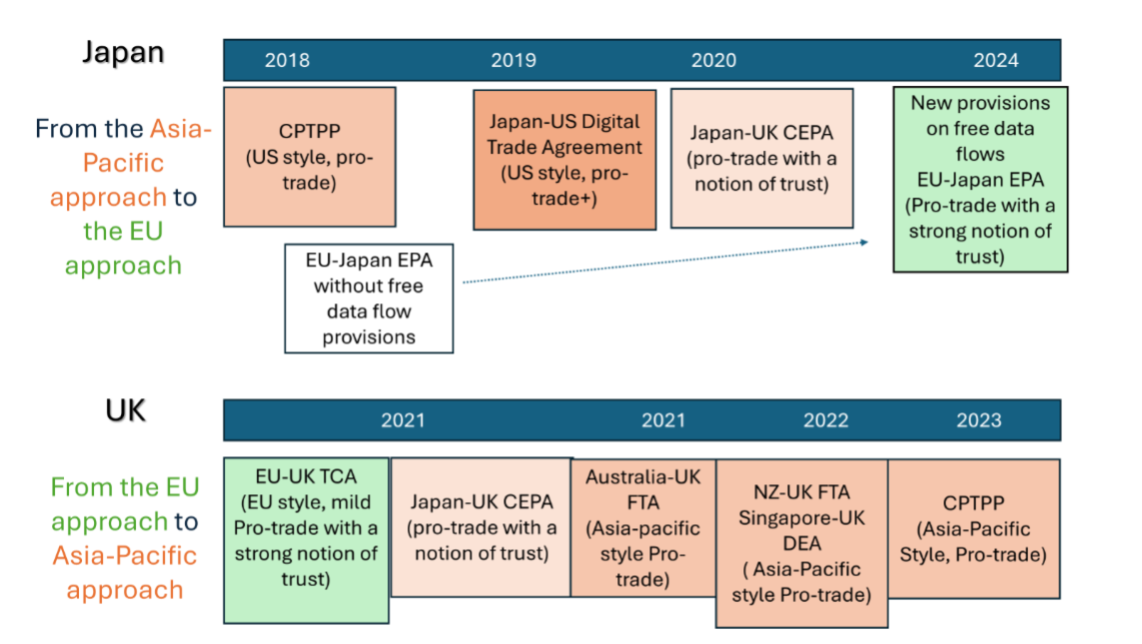

An interesting aspect here is Japan’s policy journey on digital trade agreements, which reflects a shift from the US or Asia-Pacific style pro-trade approach to the EU-style human-centric approach. The starting point of Japan’s policy journey was the CPTPP e-commerce chapter (originally the TPP e-commerce chapter) which strongly reflected US tech-companies’ desire for a laissez-faire international digital environment. The agreement prioritises free data flows with a very narrow public policy space. Under the Japan-US Digital Trade Agreement (DTA), the Japanese government accepted the US approach, which leans even more towards business interests than the CPTPP.

Subsequently Japanese policy preference shifted more towards the EU’s human-centric approach. The Japan-UK Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) signed October 2020, which reflects both the CPTPP and the EU-UK TCA, could be seen as a first step in this direction.

Why the change? At the domestic level, data privacy regimes have been legally and institutionally strengthened over the last decade. At the international level, the Japanese government has been advocating the new norm of “Data Free Flow with Trust” from 2019 through G7, G20, OECD and beyond.[1] The Japanese government considers that the new EU-Japan protocol, incorporating the principle of “DFFT”, will contribute to a more balanced approach to digital trade and could become a model of a 21st century digital trade agreement.

In contrast, the UK’s policy journey has unfolded in the opposite direction (Figure 1). Other than the EU-UK TCA, the UK has tended to depart from the EU style digital governance approach. With the tilt to the Indo-Pacific, the UK has aligned itself more to the Asia-Pacific style market-driven approach to digital trade governance. The digital trade rules under the Australia-UK FTA, UK-New Zealand FTA, and Singapore-UK DEA are modelled on the CPTPP.

Indeed, the Conservative UK government’s efforts to reform of the UK data protection regime (Data Protection and Digital Information Bill), reflects a drift away from EU-style data governance. It has also enabled the UK to strike these digital trade deals. The reforms prioritised data-driven innovation with an ambition of making the UK an international data hub, but legal experts raised concerns over their ethical, social and legal implications.

The Labour Party manifesto was silent about digital trade governance, and the approach of the new government to digital trade is an important question as it will, in part, shape tomorrow’s world.

At the multilateral level, we have entered a new phase of negotiations. It seems that cross-border data flows provisions are being dropped from the on-going WTO Joint Statement Initiative (JSI) negotiations on e-commerce. This is because of the lack of support, if not opposition, from the US as it wants stronger tech regulation. Although there was not a consensus over the balance of free data flows and public policy objectives even before the US’s objections, the US’s position has proved a key obstacle to multilateral rules on data flows. Under such circumstances, promoting a new digital trade model like the EU-Japan new agreement and the UK-EU TCA could help mitigate US’s concerns over limited public policy space.

The quality of the UK’s data governance is ranked as world-leading according to the Global Data Governance Mapping Project. This means that the UK is well positioned to show the best practice to its trade partners while enhancing the trust side of digitisation and promoting digital trade at the bilateral, plurilateral and multilateral levels.

With the new UK government, there is an opportunity to revisit its role at the international level. Given that the Labour government values individual / human rights while promoting innovation, the UK could play an active role in forging a broader consensus on the balance between free data flows and public policy space. As part of it, it seems natural for the UK to collaborate with Japan and the EU to promote the balanced approach achieved under the EU-UK TCA and the EU-Japan EPA. This could help regain support from the US administration for the WTO negotiations and other international forums.

[1] As for “DFFT” and its relation with trade policy, see “Can trade policy enable “Data Free Flow with Trust?“

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher July 23rd, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

3 July 2024

Tom Arnold is a Researcher at the Heseltine Institute for Public Policy, Practice and Place at the University of Liverpool; Patrick Holden is a Reader in International Relations at the University of Plymouth; Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School; and Ioannis Papadakis is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Inclusive Trade based at the University of Sussex.

Freeports have been a central part of the UK Government’s regional development policy over the last five years. The 2019 Conservative Party manifesto pledged to create “up to ten Freeports around the UK”,[1] emphasising their potential to create new jobs and additional income streams for local government. They were also promoted as key to improving the UK’s international trade prospects following its exit from the European Union. UK government has specified three economic objectives for Freeports: to establish them as hubs for global trade and investment; to promote regeneration and job creation; and to create hotbeds for innovation.[2]

Despite this, Freeports have not featured strongly in the current general election campaign. The 2024 Conservative manifesto includes a promise to “create more Freeports and Business Rates Retention zones”, emphasising their potential to create new jobs and provide additional income streams to local government.[3] While the opposition Labour Party pledges to develop Local Growth Plans aligned to national industrial strategy, there is no mention of Freeports.

The UK Freeport programme looks likely to continue in some form, regardless of the outcome of the election. The 2023 Autumn Statement extended tax relief funding for English Freeports from 2026 to 2031, meaning Freeport operators and occupiers will benefit from reliefs on stamp duty, business rates and employer national insurance until this ‘sunset date’. Nevertheless, several concerns will need to be addressed by the next government. This piece sets out the key issues for Freeports over the coming months and years, and suggestions for improving on the current model.

In April 2024, the House of Commons Business and Trade Committee published the findings of its inquiry into the performance of Freeports and investment zones in England, to which some authors of this article contributed evidence.[4] The report summarises the benefits and limitations of the UK Freeport model, highlighting evidence which suggests:

Despite these concerns, we argue that the UK Freeport experiment should not be abandoned, but may need modification. Given the limitations of the customs benefits associated with Freeports, the government should focus on the role they can play as part of an active, place-based industrial strategy. While Freeports have been portrayed as a central element of the government’s ‘Levelling Up’ regional development policy, the relationship with broader government objectives on key national issues such as net zero is unclear.

This confusion is partly a result of the dual purpose of the current UK Freeport model, which aims to both boost international trade and operate as traditional Special Economic Zones with a focus on attracting jobs and regenerating ‘left behind’ places. Aligning Freeports more closely with national policy targets and providing greater certainty about the purpose of regional policy could help to clarify their purpose. This could be particularly significant in places which continue to face acute socio-economic problems following the mass decline of industry in the second half of the 20th century.

To achieve this, we highlight five areas for improvement in the current government’s strategy for Freeports.

Align with other special economic zones. In addition to Freeports, there are two other main special economic zone (SEZ) programmes currently operational in the UK: Investment Zones (introduced in 2023, with 13 across the UK); and Enterprise Zones (introduced in 2011 and expanded in 2016, with 48 across England only). The presence of three different types of SEZ presents complexities for local government in attracting investment and developing industrial strategy, particularly in areas where all three are present (such as Liverpool City Region). As part of a broader industrial strategy, the government should be clear about the purpose of each SEZ and where possible align governance of SEZs under a single accountable body (such as a Mayoral Combined Authority. Where appropriate SEZs could be merged to create clusters with complementary activities – comprising universities, ports and dynamic SMEs. There is particular potential to align Freeport activity with national and local objectives to achieve net zero carbon emissions, particularly through decarbonisation of freight transport.

Assess the value of customs benefits. The government should review whether customs reliefs are worth retaining or should be wound down to save money and time for local authorities and to allow more focus on the place-based industrial policy elements of the programme. Policies and funding could be focused more narrowly on other Freeport priorities such as improving infrastructure and upskilling local workers. The UK Freeport model should be understood more accurately as a type of SEZ rather than a focus on international trade.

Enhance governance. The Business and Trade Committee report recommends that accountability for Freeports should be held by a single leader, in the form of an elected ‘metro mayor’. This can offer clarity for businesses, the public and other stakeholders. However, only three English Freeports are currently located in areas with a mayoral combined authority (East Midlands, Liverpool City Region and Teesside). For Freeports without an elected mayor, it is less clear who the single accountable figure should be, but local authority leaders may be most appropriate for this role. While Freeports should be enabled to exercise flexibility in shaping policies to align with local aims and objectives, the UK government should retain overall scrutiny of the Freeport programme in England.

Improve transparency. While fears about the disconnection of UK Freeports from democratic accountability are exaggerated, public concern is understandable given the shortage of publicly available information about their geographies and powers. Efforts should be made to ensure all Freeport bodies publish clear, accessible and easy to digest information about site locations, governance arrangements and mechanisms for allocating retained business rates.[10] Making this information publicly available will facilitate learning about the effectiveness of UK Freeports.

Improve evaluation. The government should work with Freeports to develop metrics tracking benefits to businesses, the effectiveness of Freeport policies, and the costs and benefits of tax reliefs. The current Freeport programme has a strong monitoring and evaluation system in place at the national level, but there are challenges in the provision of local data and developing sound counterfactuals.

While Freeports have not featured strongly in the 2024 general election campaign, the issues the current UK Government purports that they resolve – particularly improving economic prospects in ‘left behind’ places – will remain central to the success of the next government. We suggest not throwing the baby out with the bathwater but reassessing the UK Freeport model as part of a broader place-based industrial strategy, including due scepticism regarding the trade effects.

[1] Conservative Party manifesto (2019) https://assets-global.website-files.com/5da42e2cae7ebd3f8bde353c/5dda924905da587992a064ba_Conservative%202019%20Manifesto.pdf (p.57)

[2] HM Treasury (2020) Freeports: bidding prospectus. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/935493/Freeports_Bidding_Prospectus_web_final.pdf

[3] Conservative Party manifesto (2024) https://public.conservatives.com/static/documents/GE2024/Conservative-Manifesto-GE2024.pdf

[4] House of Commons Business and Trade Committee (2024) Performance of investment zones and freeport in England. https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/44455/documents/221158/default/

[5] Peter Holmes and Guillermo Larbalestier (2021) Two key things to know about Freeports. https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2021/02/25/two-key-things-to-know-about-Freeports/

[6] Peter Holmes, Anna Jerzewska and Gullermo Larbalestier (2022) ‘Exporting from UK Freeports: Duty Drawback, Origin and Subsidies.’ UKTPO Briefing Paper 69. https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/files/2022/09/BP-69-Freeports-FINAL-28.09.22.pdf

[7] House of Commons Business and Trade Committee (2024)

[8] Business and Trade Committee (2023) Oral evidence: the performance of investment zones and Freeports in England. https://committees.parliament.uk/oralevidence/13744/html/ (Q9)

[9] Tees Valley Review (2024) https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65ba58ec3be8ad0010a081a9/Tees_Valley_Review_Report.pdf

[10] Nichola Harmer, Patrick Holden and Guillermo Larbalestier (2023) Written evidence submitted to the Business and Trade Committee inquiry into the performance of investment zones and freeports in England. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/124415/html/

Additional Information

The authors would like to thank Guillermo Larbalastier for earlier research input and advice. Guillermo is not responsible for any views expressed in this article. The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Charlotte Humma July 3rd, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised