What is the Most Favoured Nation (MFN) clause?

The wild world of EU MFN clauses

National Treatment & MFN combined

Asymmetric MFN clauses in goods trade

Comprehensive MFN clauses in services and investment

Impact on market access and national treatment commitments

Implications for a future UK-EU deal

Implications for improving on EU FTAs

We don’t yet know what the future trade relationship between the UK and the EU will look like. While some argue for a clean break from the EU, most proposals floated by the UK Government typically seek to achieve better access to the EU than other countries, such as Canada and Japan, have achieved in the past. With over two years of Brexit negotiations to date, we know that squaring this with the EU’s strong belief in no ‘cherry-picking’ is proving tricky. A more technical detail, the so-called Most Favoured Nation (MFN) clause contained in several of the EU’s existing trade agreements, could also limit the extent of concessions granted by Brussels to the UK.

This Briefing Paper explains what the MFN clause is and why it could be problematic for the UK. It maps out which EU agreements contain MFN clauses, their scope and the various exceptions they contain.

MFN clauses have been around for centuries,[1] and feature centrally in the WTO, primarily through Article I of WTO’s General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT, 1947), and Article II of the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS, 1994). In essence, these MFN clauses are designed to prevent a country from discriminating between WTO members, by requiring each country to extend to all other WTO members any preferential treatment granted to another party. More specifically, Article II of the GATS states:

“With respect to any measure covered by this Agreement, each Member shall accord immediately and unconditionally to services and service suppliers of any other Member treatment no less favourable than that it accords to like services and service suppliers of any other country.”

The WTO allows for some exceptions to this obligation. Particularly, if two or more countries enter into a broad trade agreement they are entitled to grant each other better treatment, without having to extend this to other countries.[2]

In addition to the WTO’s MFN clauses, the EU has included MFN clauses in a number of its own free trade agreements (FTAs). As we will see, the scope of these MFN clauses varies between agreements. In their most comprehensive form, they apply to different circumstances from their WTO equivalents; they act as safeguards to ensure that preferences granted in one trade agreement are not eroded by one of the parties subsequently granting better treatment to another country in a future trade agreement. In such cases, the MFN clauses stipulate that any further preferences granted in a future trade agreement must also be extended to the parties of the original agreement.

This requirement could limit the EU’s willingness to offer the UK better treatment in a future trade deal if it means that it must also extend the same treatment ‘for free’ to a number of its existing FTA partners. Further, it imposes an even larger constraint on the partners to the FTAs, which would be obliged to extend to the EU any more-favourable treatment offered to the UK. It is therefore important for UK negotiators to understand where these MFN clauses exist, what they cover and the potential exceptions that apply.

The EU has some 37 trade agreements in place with more than 60 countries and they differ in depth and scope. A few agreements have no MFN provisions at all but most contain MFN clauses to some extent. Navigating these can be tricky: the areas covered under MFN differ, the clauses can be complex and are typically accompanied by a number of qualifications and restrictions which take different forms. The analysis here focuses on outlining general MFN clauses for goods, services and investment. While many of the agreements under consideration also contain MFN provisions related to intellectual property rights, these are not covered here.

Although there is a degree of variation in the texts, Figure 1 approximately groups the EU’s agreements into five different categories of MFN.

The EU has a number of Association Agreements (AAs) in place with limited MFN obligations. Most of the EU’s AAs with its Euro-Mediterranean partners merely reiterate the MFN obligations of the GATS. Such MFN obligations apply to chapters on the right of establishment and supply of services, but do not apply to preferences granted in other trade agreements. The EU-Mexico agreement of 2000 has an MFN clause which resembles the GATS MFN, but goes further than the GATS by stipulating that, with respect to other FTAs, the parties shall “afford adequate opportunity to the other Party to negotiate the benefits granted therein”.[1]

A number of the EU’s other AAs, including all of the Stabilisation and Association Agreements (SAAs), have a combined National Treatment and MFN clause applying to chapters on the right of establishment. These clauses commit the parties to accord to the other party treatment no less favourable than that which is granted to its domestic companies or to any third country, whichever is better. These clauses suggest the possibility of more favourable treatment being accorded to foreign firms, but in reality, this is very rare, so the impact of these clauses is likely to be limited.[2]

The EU has 7 Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs) in force with 29 countries in Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific (ACP). These are reciprocal, but asymmetric, trade and development agreements. While the EU largely commits to duty-free and quota-free access for all goods (except arms and ammunition), the ACP parties’ commitments are generally less extensive and implemented gradually, often amounting to a reduction of tariffs for around 80-85% of EU imports and frequently excluding sensitive products such as agricultural and food products.

These agreements contain asymmetric MFN clauses with respect to customs duties on goods. Unlike their GATT equivalents, they are extended to also cover preferences granted by either party in future trade agreements. While the EU is required to accord to the relevant ACP party any more-favourable treatment that it grants in any future trade agreement, the ACP parties are only required to do so if more favourable treatment is granted to a ‘major trading partner’. This is defined as any developed country, any country accounting for at least 1% of world merchandise exports or any group of countries accounting collectively for at least 1.5% of world merchandise exports.[3] The MFN obligations are relaxed further in CARIFORUM and SADC’s EPAs by simply committing the parties to enter into consultations if more favourable treatment is granted by the ACP party, with a view to deciding whether the same treatment should also be extended to the EU.[4]

Given that there is limited scope for the EU to liberalise tariffs further, the commitments in these MFN clauses have relatively little impact on the EU. In contrast, fears have been raised both by ACP countries and others, that these MFN clauses may hinder future trade agreements between the ACP and third countries. The ACP parties typically have scope to make further tariff concessions than have been committed in the EPAs, but the MFN clauses may limit their willingness to do so since they risk having to offer to the EU any further preferences granted to a third country. This clearly constrains the ACP parties, but may also discourage countries which would qualify as ‘major trading economies’ (such as Brazil, China and India) from engaging in trade talks with the ACP, because they would prefer to have uniquely privileged access to the ACP party market. If this is true, it will constrain the ACP from diversifying their trading partners. [5]

The MFN clauses in the EPAs are limited to customs duties on goods, except for the EU-CARIFORUM EPA. This is a comprehensive agreement which, in addition to goods trade, includes provisions on cross-border services and investment and contains similarly asymmetric MFN clauses in these dimensions.

The EU’s 2006 Global Europe trade strategy saw the launch of a ‘New Generation’ of trade agreements covering a broad set of issues, and generally including somewhat more extensive chapters on services and investment. Around the same time, it appears that the EU adopted a new strategy regarding its MFN provisions, perhaps as a result of the 2006 ‘Minimum Platform on Investment for EU FTAs’.[6] This provided a template for a chapter on ‘Establishment, trade in services and e-commerce’ and contained an MFN clause closely resembling those now observed in most of the EU’s new generation trade agreements.[7]

Similar to the EU’s MFN clauses in the EPAs, these MFN provisions commit both parties to granting the other party any more-favourable treatment accorded to a third country, irrespective of whether this is done through a trade agreement or not. The agreements with Canada, South Korea and Japan all contain such MFN clauses and, as mentioned, the EPA with CARIFORUM also has a similar clause, applying asymmetrically to the CARIFORUM parties. Further, judging from the draft texts, the EU’s proposed agreement with Vietnam as well as the updated EU-Mexico agreement currently under negotiation will both contain similar MFN provisions. All of these agreements have come into force, or are still being negotiated since the EU’s new strategy was launched. The one exception appears to be the EU-Singapore agreement (yet to be signed) which is part of the ‘new generation’ agreements but which does not appear to contain any general MFN clauses.[8]

Table 1 summarises the coverage and the relevant articles of the MFN clauses in the six trade agreements in this group.[9] Subject to a number of sectoral exceptions, all agreements apart from EU-Vietnam cover cross-border trade in services (modes 1 and 2) and all of the listed agreements cover right of establishment (mode 3). EU-Canada and EU-Japan further extend the MFN clauses from the investment and/or cross-border services chapters to the chapters on temporary entry and stay of natural persons (mode 4).[10] The CARIFORUM agreement also includes a general MFN clause applying to customs duties on goods, and EU-Japan, EU-Mexico and EU-South Korea all apply MFN to limited sections of goods trade. These applications are ‘necessary’ because in each case the free trade agreement leaves a few tariffs in place on imports from the EU. The latter does not want to face these tariffs if another party does not.

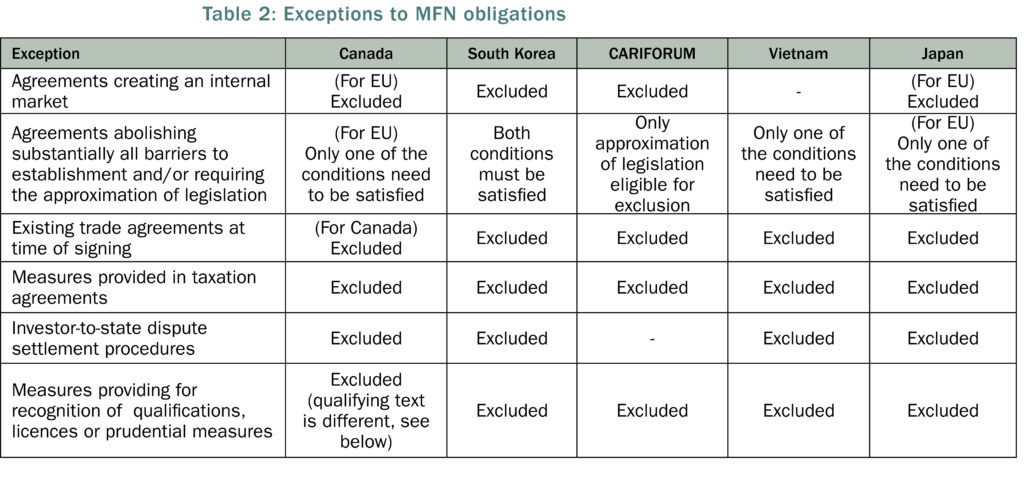

There are specific conditions under which the MFN clauses discussed above no longer apply, these are summarised in Table 2. The new EU-Mexico agreement has been excluded as the text is in an early draft stage and not comprehensive enough to reliably draw conclusions on the exceptions that may apply.

Overall, agreements related wholly or mainly to taxation are excluded from MFN in all the agreements in question. Further, all agreements except EU-Canada (“CETA”) exclude any existing trade agreements, whereas in CETA only Canada makes this exception.[1] This supports the notion that, at least at the point of signature, CETA really was the most comprehensive trade agreement with respect to services signed to-date by the EU, since if the EU had previously granted any better treatment to another country in an existing FTA, the same treatment would have had to be extended to Canada in the relevant dimensions.

Agreements creating an ‘internal market’ in services and investment are excluded in all agreements except in EU-Vietnam, and they all exclude agreements that abolish, in substance, all barriers to establishment and/or require the approximation of legislation. As can be seen in Table 2, in CETA and EU-Japan, these exceptions apply only to the EU and are made through specific reservations in separate Annexes. Further, in EU-South Korea both the right of establishment and approximation of legislation must be satisfied in order to be excluded from MFN, whereas the other agreements require only one of the conditions to be satisfied. These exceptions will be discussed in some more detail in the next section.

Finally, all five agreements in Table 2 contain exceptions for measures providing for recognition. All except CETA exclude the following:

“measures providing for recognition of qualifications, licences or prudential measures in accordance with Article VII of GATS or its Annex on Financial Services”[1]

The recognition exception is worded differently in CETA, stating that:

“ (…) treatment accorded by a Party under an existing or future measure providing for recognition, including through an arrangement or agreement with a third country that recognises the accreditation of testing and analysis services and service suppliers, the accreditation of repair and maintenance services and service suppliers, as well as the certification of the qualifications of, or the results of, or work done by, those accredited services and service suppliers.”[2]

In addition to these general exceptions, each agreement contains a number of specific sectoral reservations, limiting the MFN obligations in specific sectors and giving the parties more flexibility to grant better treatment in the future in these dimensions.[3]

MFN clauses typically apply to both market access provisions and national treatment commitments. Market access restrictions are potentially discriminatory – one partner could be favoured over another – and MFN clauses aim to assure partners that they will not suffer in this way as a result of a future trade agreement. National treatment measures, on the other hand, distinguish between domestic and foreign suppliers but not between the latter – they apply equally to all imports. Thus, if a trade agreement results in a more liberal national treatment rule (or liberalises the rule for both domestic and foreign suppliers) that change is automatically extended to suppliers from countries other than the negotiating partner. That is, MFN treatment arises automatically from the nature of the restriction and MFN clauses have no further effect. Thus, to the extent that services trade is restricted by national treatment issues, MFN clauses barely affect the incentives for liberalisation. But since it cannot be guaranteed that a party will never be able to grant a benefit to one country but not to another, MFN clauses offer some comfort.[4]

The EU typically liberalises close to 100% of tariffs on goods trade in its trade agreements, so it seems likely that the UK would be able to negotiate tariff-free access to the EU with relative ease. Services are a different story entirely, and FTAs tend to offer relatively little in these dimensions. Services are of great importance to the UK economy, accounting for 40% of the UK’s exports to the EU in 2017.[5] It should, therefore, be a priority for the UK to retain suitable access to the EU’s services market post Brexit, which is why the comprehensive MFN clauses with respect to services and investment are potentially problematic for the UK.

If the EU granted the UK significantly better access to its services markets, this would mean that the same treatment would need to be extended to Canada, South Korea, all CARIFORUM countries, Japan, Vietnam and Mexico ‘for free’ (assuming that Vietnam and Mexico’s agreements enter into force before a potential UK-EU deal). Although these countries may not be large enough to make such concessions to the UK impossible, they will surely be a discouragement. To avoid this, the UK could utilise the exceptions to MFN listed in Table 2. In particular, the following exceptions could be relevant:

In CETA, an internal market is defined as “an area without internal frontiers in which the free movement of services, capital and persons is ensured”. Thus, a ‘soft Brexit’, such as EEA membership whereby the UK remains part of the EU single market, would satisfy option one.

The approximation of legislation requires the alignment of the legislation of one party with the legislation of the other party, or the incorporation of common legislation into the law of the parties. The right of establishment requires, in substance, that all barriers to establishment be eliminated between the parties. FTAs rarely mandate such deep levels of integration and alignment, as evidenced in CETA, where both EU members and Canada maintain a number of barriers to establishment, such as foreign equity restrictions or requirements for a specific type of legal entity. Thus, similar to option one, satisfying these conditions would require an agreement stipulating much closer integration with the EU than any standard FTA would entail.

Exclusion 3 covers mutual recognition agreements. For example, if the UK and the EU agree to continue to mutually recognise each other’s professional qualifications post-Brexit, it would fall under this MFN exemption. Some argue that this exception would also cover passporting rights in financial services as this is based on mutual recognition, but would likely also require some form of regulatory alignment.[6] More generally, if the UK and the EU negotiate a mutual recognition agreement with respect to licensing or qualifications requirements, the MFN clauses would not require the EU to also extend mutual recognition unconditionally to Canada, South Korea, or Japan. Rather, the EU should simply offer adequate opportunity for these parties to negotiate mutual recognition on the same grounds as granted to the UK.[7] Both the British Prime Minister and the Chancellor have, in the past, advocated for a system of mutual recognition post-Brexit, in areas such as broadcasting and financial services.[8] However, unless the UK accepts EU oversight of its rules, the EU has so far ruled out this option from fears that UK regulations will diverge from EU rules over time.[9]

As mentioned above, each agreement contains numerous exceptions to the MFN clause, where a party reserves the right to afford better treatment to a third party in the future without invoking the MFN clause. Where the EU has made such exceptions it is technically free to offer the UK better treatment, although this, of course, does not guarantee that it would.

Outside the EU, the UK would be free to negotiate its own trade agreements, something which supporters of ‘Global Britain’ champion as a key benefit of Brexit. However, should the UK wish to re-negotiate the terms of the existing EU agreements post-Brexit, the MFN obligations discussed above appear to virtually prohibit the parties to these agreements from granting any better treatment, with respect to services and investment, to the UK than has already been granted to the EU. If they did, they would be required to extend the same concessions to the EU, an economy six times the size of the UK, ‘for free’. This seems like a price too high to pay.

For the same reason, given that the UK qualifies as a ‘major trading partner’, the MFN obligations in EU’s EPAs would almost certainly discourage the ACP parties from according any further tariff reductions to the UK than have already been granted to the EU. As a result, although after Brexit the UK will be able to negotiate on its own, where MFN clauses apply it seems unlikely that it will be able to improve on the terms of the existing agreements.

This Briefing Paper outlines which EU trade agreements contain MFN clauses, their scope and the various exceptions that apply. As we have seen, a number of the EU’s trade agreements contain MFN clauses. In particular, most of the EU’s recent trade agreements with partners such as Canada, South Korea and Japan include MFN obligations with respect to services and investment, areas of importance to the UK. While some exceptions and sectoral carve-outs exist, these are narrow in scope and typically require very close integration between the parties, more closely resembling the EEA than a ‘Canada-style’ FTA.

MFN clauses should not be viewed as a mere technical detail. MFN raises the cost of granting the UK further concessions in a future trade deal, as this would have to be granted for free to all existing FTA partners where MFN clauses apply. Unless the UK can utilise the exceptions to MFN, these clauses could well impede UK negotiations both with the EU, and, perhaps even more so, with the EU’s FTA partners.

[1] See: EU-South Korea Article 7.8.3(a), EU-CARIFORUM Article 70.3(a), EU-Japan Article 8.9.3(b), EU-Vietnam Article 8.6.4(c)

[2] EU-Canada Article 9.5.3. It is not entirely clear to us whether the difference in wording significantly changes the scope of this exception. CETA makes explicit that accreditation processes, as well as the certifications themselves, are excluded, which could be seen to expand, or clarify, the scope of the exception.

[3]For a summary of the sectoral MFN obligations in the EU-Canada agreement, see Magntorn, J., Winters, L. A. (2018) “European Union services liberalisation in CETA”. Working Paper Series 08-2018, Department of Economics, University of Sussex

[4] The fact that services trade is often governed by national treatment regulations and that these have an automatic MFN dimension, helps to explain why progress on liberalising services via trade agreements tends to be modest. The partner which is ‘buying’ the liberalisation by making its own concessions in negotiation is ‘buying’ it on behalf of all suppliers and thus gets only a part of the extra trade so created.

[5] Ward, M., (2018) “Statistics on UK-EU Trade” House of Commons Library, Briefing Paper Number 7851

[6] Barnard, C., Leinarte, E., (2018) “Most favoured nation principle: a problem for UK’s financial services?” The UK in a Changing Europe

[7] See: Oral evidence: The progress of the UK’s negotiations on EU withdrawal, HC 372, (Q1256) 21/03/2018 to Committee on Exiting the European Union

[8] See for example Theresa May’s Mansion House speech (02/03/2018) and Philip Hammond’s Canary Wharf HSBC speech (07/03/2018)

[9] Brunsden, J., (13 March 2018) “Barnier: UK yet to face up to ‘hard facts’ of Brexit” Financial Times

[1] See Reservation II-C-20 in Annex II of CETA, listing Canada’s reservations.

[1] See Article 5 of the EU-Mexico Economic Partnership, Political Coordination and Cooperation Agreement.

[2] Some exceptions may apply, for example with regards to investor-state dispute-settlement which is only available to foreign operators. Further, as discussed by Sébastien Miroudot, some countries may provide specific incentives to foreign investors such as subsidies or tax holidays which are not available to domestic firms. For more, see Miroudot,S. (2011) “Investment” in Chauffour, Jean-Pierre; Maur, Jean-Christophe (eds.) Preferential Trade Agreement Policies for Development : A Handbook, Washington, DC: The World Bank, pp. 307-26

[3] See for example Article 17.6 in the EU-Ghana EPA

[4] See Art. 19.5 in EU-CARIFORUM and Art. 28.8 in EU-SADC. In EU-SADC, according to Art. 28.7, the reverse also applies for the EU with respect to South Africa only.

[5] For more on this see discussion in Bartels. L, (2011) “The EU’s Economic Partnership Agreements with

African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries” ACLE Law & Economics Seminars Amsterdam

[6] In WTO, trade agreements on services are termed Economic Integration Agreements, but we continue here with the common, looser, usage that Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) can cover both goods and services.

[7] For a further discussion of the Minimum Platform and its impact on EU trade policy see Siles-Brügge, G., (2014) “Constructing European Union Trade Policy: A Global Idea of Europe” Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

[8] According to a European Parliament study there is a partial MFN clause in EU-Singapore in relation to banking licences. See European Parliament, Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies (2018) “Free Trade Agreement between the EU and the Republic of Singapore – Analysis” for more information.

[9] Table 1 outlines the coverage of the MFN clauses according to the 4 modes of supply. While some agreements cover all services sectors in the same chapters, other agreements, such as CETA and the new EU-Mexico agreement, contain separate chapters for certain services sectors (such as financial services). These chapters may consequently contain specific MFN clauses in addition to the Articles listed in Table 1. See for example Art. 13.4 in CETA (on Financial Services), and article XX.4 in the Financial Services chapter in latest draft of the new EU-Mexico agreement.

[10] The articles incorporating MFN to the chapters on temporary entry of natural persons in CETA and EU-Japan (Art. 10.6 in CETA and Art. 8.24 in EU-Japan) are complex and need to be evaluated carefully. The wording of the two articles differ slightly, which in return may result in differing scope of the articles.

[1] Hestermeyer, H. (2017) “What is the Most-Favoured-Nation Clause?” UK Trade Forum

[2] For further details on this, see Lydgate, E., and Winters, L.A., (2018) “Deep and not comprehensive? What the WTO rules permit for a UK-EU FTA” World Trade Review, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474745618000186, Published online: 29 May 2018