Why is Trade a ‘Good Thing’…But Not Necessarily For All?

Winners and Losers: What is the Evidence?

Watch: Briefing Paper Launch and Panel Discussion

Economists have long argued, and with good justification, that international trade brings overall benefits to economies. However, increasing trade is likely to create losers as well as winners. Indeed, within a broader context of rising inequality in many countries, recent years have seen growing public concern surrounding the negative consequences of trade and globalisation for certain sectors of society.[1] Those concerns, in turn, are seen as being partly responsible for the rise in populism in some developed countries.[2]

Given such developments, and as the UK prepares to leave the EU and have an independent trade policy, it is important to understand how future trade agreements, or policy changes, may affect economic outcomes such as prices, productivity and output, and through these, individuals and regions.

The aim of this Briefing Paper is, therefore, to sketch out how trade changes may result in ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ – be these consumers, workers, regions, or industries. Our focus is primarily on developed countries, and on within-country impacts rather than cross-country effects. We first provide a conceptual background which outlines the causal mechanisms which may lead to winners and losers. We then summarise the empirical evidence on these mechanisms and discuss potential policy responses.[3]

Most economic changes produce winners and losers, and this is also true for changes in trade. In this section we consider what drives international trade and why trade may have such distributional consequences.

Opening up to international trade (i.e. trade liberalisation) allows a country, and the consumers and firms in that country, to buy more goods from more countries. Not only does the value of imports rise, the increase in trade is typically accompanied by more specialisation. In 1965, for example, motor vehicles accounted for 1% of total UK goods imports, and by 2018 they accounted for over 11%; similarly, medicines and pharmaceutical products accounted for less than 0.2% of imports in 1965, and nearly 5% in 2018; and the import share for clothing grew from less than 1% to over 4%.[4]

Why do we buy these imported goods as opposed to those produced domestically?

(a) these goods may not be available from domestic sources,

(b) they may be cheaper, or

(c) of higher quality, or

(d) they may simply be ‘different’ from those produced domestically.

Consumers and firms who are now able to buy (cheaper) imported goods are obvious winners from trade: imagine being restricted to drinking only Welsh Claret! But increasing imports brings competitive pressures which may also result in domestic industries and sectors declining, and losing out from trade.

Opening up to trade also enables firms to sell to new buyers and markets. Again, not only does the value of trade rise, but the expansion of exports leads to increased specialisation. For example, aircraft accounted for around 1% of UK exports in the early 1960s and over 4% in 2018; the share of power generating machinery in exports was around 4% in the earlier period, rising to over 7% in 2018.[5] The firms which expand their sales from access to new export markets are therefore also winners, as are their workers.

Generally, more trade is beneficial for the overall economy, but unless there is some redistribution of the overall gains, there will likely be welfare losses for some.[6] Note that, typically, the gains are spread across many consumers, whereas the losses are much more concentrated – be this by worker type, industry or locality. Hence, while there are more winners than losers, an individual loser typically loses much more than any individual gains and thus the losers have the greater incentive to oppose the liberalisation.

1. Specialisation: The classic explanation is based on the principle that countries should specialise in what they are relatively better at, driven by countries being in some way different from each other. Countries with lots of skilled labour can produce skilled-labour-intensive goods and services relatively cheaply (aircraft, banking), those with lots of fertile land can produce agricultural products at lower cost, and those with better technology for producing industrial pumps, say, will have cheaper pumps.[7]

As trade increases, countries specialise more in those things that they are relatively good at and this increases the overall value of output and income. But as we have noted, some sectors will expand while others contract, cutting jobs or even driving some firms out of business. These changes may also affect wages within a country – if high-skill-intensive sectors expand, there will be increased demand for highly skilled workers, pushing up their wages. Conversely, if low-skill-intensive sectors contract, laying off their workers, this puts downward pressure on low-skill wages. In the short run there may also be increased unemployment depending on the net effects in any locality.

2. Within industry reallocations: In the preceding explanation, trade and the distributional impacts of trade, are driven by differences between countries (such as labour, land, capital or technology). However, trade also occurs even if countries are similar. Indeed, much of world trade is between similar developed countries (i.e. North-North) rather than between developed and developing countries (i.e. North-South).

As consumers, we like to have choice and variety. In addition, if there are economies of scale in production, then it makes sense for some firms to concentrate on some varieties (e.g. Ford cars), and for others to concentrate on a different range (e.g. Volkswagen), and these firms may well be located in different countries. Since some consumers want Fords, and others Volkswagens, trade will occur.

Opening up to more of this sort of trade also leads to winners and losers at the firm level, with less efficient firms contracting (or going out of business) and the more efficient expanding (or entering the industry). Therefore, even if there are no specialisation changes as described in (1) above, such that the share of an industry in imports or exports remains fairly constant over time, international trade can still lead to substantial changes within the industry. Substituting more efficient for less efficient firms increases average productivity and so is good for the economy as a whole. Consumers and firms buying intermediates benefit by getting products at lower prices, and their choice may increase as trade adds foreign varieties to the available range.

3. Productivity and growth: The previous two causal chains implicitly assumed given levels of technology and given sets of inputs such as land, capital, or labour. They were then concerned with the best way of organising who produces what, and sells to whom.[8] But over time there may also be trade-induced improvements in productivity, for example, from economies of scale or scope, from increases in investment and research and development stimulated by larger markets, from reductions in inefficiencies due to increased competition, or from positive spillovers between firms.[9]

Productivity change has complex effects on who gains and loses. There may be consumer gains through more product varieties, lower prices, or higher quality of goods and services, and gains from higher wages induced by higher productivity. But technological change may affect sectors’ competitiveness, and impinge differently on the owners of different inputs. For example, technological change could be biased against low-skilled labour, and hence reduce low-skilled wages across all sectors of the economy. Equally, it could increase the demand for some workers, e.g. computer programmers.

If technological change increases workers’ productivity this should be reflected in higher wages. However, such a change typically means getting more output for less input, which may, in turn, imply a need for fewer workers for the same level of output. So, while those working in such sectors might get higher wages, fewer workers might be demanded, which implies ambiguous effects for labour as a whole.

4. Agglomeration: As opposed to being evenly spread across a country, economic activity concentrates geographically. Think of Silicon Valley in California, the concentration of car production in the Midlands or the North East of the UK, or the agglomeration of financial services in London. Such agglomeration raises aggregate efficiency, but can also lead to an uneven regional distribution of economic activity and incomes – a core-periphery pattern. The greater the mobility of labour and capital, the more likely this may be.[10]

Agglomeration occurs because there may be gains from: (a) being close to good infrastructure, such as ports or intra-city transport systems that improve firms’ access to national and international goods and factor markets; (b) being close to other firms in their industry – as this may generate knowledge spillovers or easier access to inputs; (c) being close to consumers to minimise the costs of accessing the market and also to improve knowledge about demand in the market; or (d) being close to conurbations as it gives access to a larger and possibly better pool of workers.

The breadth of the menu of possible gains from agglomeration generates complex trade-offs – for example, between being close to other firms or close to consumers – and changes in international trade policy can affect these in quite surprising ways. Improved port facilities may increase local production because products are more easily (cheaply) sold abroad, or reduce it because imports that are substitutes for local production become more easily available. HS2 may help Mancunians sell more services to London, or vice versa. Thus, while agglomeration and benefits thereof are real enough, the complex trade-offs make it difficult to predict the effects of any particular policy change.

There are two related issues which are worth underlining. First, the issue of export-led growth. A notable feature is that many of the preceding sources of gains from trade – specialisation, scale economies, increased competition, increased variety, spillovers and agglomeration – operate through facilitating imports. Exports are, of course, the means to affording increased imports, but the gains arise from increased imports. This does not mean there are no gains from exporting.

Indeed, some countries, both developed and developing, have pursued export-led strategies (e.g. Germany and Korea).[11] Having access to larger consumer markets encourages economies of scale and increases the returns to investment and innovation. Exporting may lead to productivity growth via technology diffusion and knowledge transfer from customers and competitors abroad. And being able to sell to several different markets can reduce risk, and provide a way of extending the life-cycle of a product. A pair of last-year’s sunglasses may no longer be fashionable in one market, but sell extremely well in another market.

Second, each of the above causal chains can occur over different time horizons and these time horizons will differ across sectors, industries, regions and people. In the short run, changes in trade policy can have an immediate impact. For example, the tariffs introduced by the US and China in the on-going trade war have already impacted on prices, output and workers in both America and China.[12]

Alternatively, consider Figure 1 which gives the share of cars in UK exports since the early 1960’s. This shows that the changes in specialisation have moved in both directions, with early decline followed by expansion. In 1962 the share was 11.7%, and in 2018 it was 11.6%. But the intervening years have seen dramatic changes with the share falling as low as 4.5% in the mid-1980’s.

Taking an even longer-run perspective, the 19th and 20th centuries witnessed the transformation of many economies from primarily agrarian to industrial. Concomitantly, there were big changes in the levels and patterns of trade. These were driven by a complex combination of changes in policy (land reform, political reform), and technological change impacting both on production techniques (mechanisation) and transportation (railways, steamships) leading to a significant lowering of national and international transport costs and the rapid expansion of trade. It is worth noting that while these factors were mutually reinforcing and led to dramatically higher average living standards, they also led to fundamental shifts in the distribution of incomes, leading to considerable disruption and at times social unrest.

Who is affected by changes in trade, by how much, and for how long will thus depend on the structure of each economy, the physical and institutional infrastructures, the ability of individuals and firms to adjust, the magnitude of any changes in trade, and on the short- and long-run policy responses.

Not surprisingly, this is complex and the outcomes varied. The relevant literature is substantial, and in this section we summarise a representative selection of key evidence on how economies have adjusted to changes in trade, with a focus on the impact on developed countries. We first consider the impact of trade liberalisation on people, and secondly on places.

People may be affected either as consumers and/or as workers, and the empirical literature has focused more on the latter as opposed to the former.

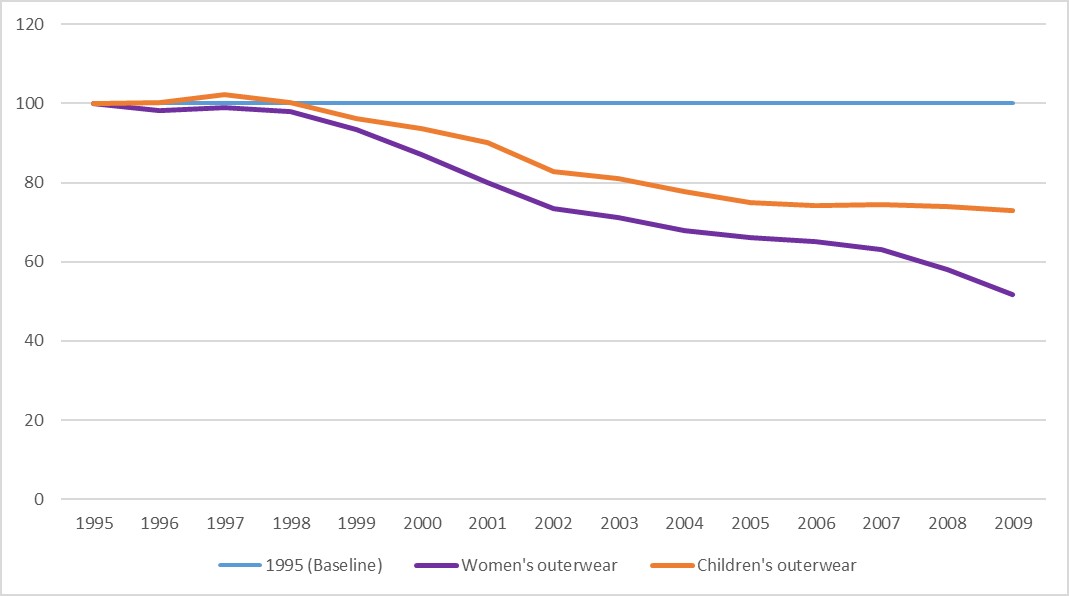

Source: ONS. Data has been re-based from 1987 to 1995, authors’ own calculations.

Take ‘people as consumers’. There is less empirical work on this as it is perhaps more obvious that lowering trade barriers decreases prices and increases the range of goods and possibly also their quality. Cross-country work suggests that trade leads to real income gains for consumers. For example, one study finds that real income in the UK could be as much as 33% lower in the absence of trade, with a similar figure for the US.[13] Alternatively if we look at specific sectors, trade in textiles used to be highly protected in the EU (and elsewhere) until the introduction of the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) in 1995. Evidence suggests that over the phase-out period of the ATC (1996-2005), consumer prices for clothing and footwear fell in the EU, on average, by 16.2% relative to the general price level, and by around 50% in the UK.[14]

Consider Figure 2 which depicts the price of ‘outerwear’ in the UK over time relative to the price of outwear in 1995 (given by the horizontal blue line). We see that the relative prices declined substantially. Of course this does not tell us why prices have declined, but it is highly plausible that the phase-out of the ATC is part of the explanation.

In a similar vein, a study of the impact on the UK of the EU’s Free Trade Agreements implemented over 1993-2013 finds a 26% increase in the quality of UK imports and a 19% reduction in quality-adjusted prices.[15] Other work finds that the US gained up to 2.6% of GDP over 1972-2001 from being able to import more varieties of goods.[16]

Another way to look at this is that introducing barriers to trade tends to harm consumers. A recent study on the welfare impacts of the 2018 US trade war with China shows that the burden of the US tariffs on China has so far fallen on US importers and consumers: the tariff increases have been almost entirely passed on through higher prices, rather than being absorbed by Chinese exporters. By November 2018, the total US welfare loss was estimated to be $6.9 billion, or $1.4 billion per month. In addition, the tariffs were found to have reduced the number of imported varieties, raising the cost of the tariffs further.[17] This study also provides estimates of the extent to which curtailing import competition allowed domestic producers to raise their prices.[18]

Finally, while consumers typically benefit from trade liberalisation, evidence supports the idea that low-income consumers tend to gain more because they tend to concentrate their spending in sectors that are traded more.[19]

It is well documented that in most developed economies the share of manufacturing, and therefore manufacturing jobs has been declining over the last 20 years or more.[20] These structural shifts impact on the composition of demand for labour, which in turn has consequences for relative wages. The compositional changes in demand for labour suggest an increased share of both high skill and low skill occupations in employment, with a decline in relative demand for medium skill workers. This is sometimes referred to as the hollowing out of jobs.[21] The structural shifts could be driven by several factors, notably changes in technology, changes in demand (as income levels rise consumers typically spend a higher proportion of income on services), or changes in trade.

In the context of the US, for example, a number of studies focused on understanding the changes in US skilled and unskilled wages in the 1980s. In this period, the US saw a decline in wage rates relative to other countries, a decline in manufacturing employment, especially among less-skilled workers, and a widening of income inequality between skilled and unskilled workers. This also occurred at a time when US engagement in international trade and investment rose substantially, raising the question of whether there was a connection between these developments.

The evidence suggested that the different changes to skilled and unskilled labour were primarily driven by changes in labour demand (as opposed to labour supply), and that both trade and technological changes were contributory factors. Studies differ on the relative importance of each. Some posit that the changes in trade were insufficient to have had such large effects, and that technological change was the more important driver, while others argue that trade was more important.[22] A twist to the story is that the changes in technology may have been in good part induced by the changes in trade.[23] The more significant role of technology in driving the observed structural changes across a wide range of countries is supported by other evidence.[24]

More recently, US manufacturing employment fell by just under 6 million between 1999-2011,[25]and, over this time, differences between skilled and unskilled wages grew.[26] This was also a period with significant changes in trade, with the growth in Chinese exports, increased offshoring, and increased fragmentation of supply chains. Again, this raises the question of the extent to which trade may have been a driver of these changes in employment. For example, there is some evidence that offshoring to low-income countries, as well as increased import competition, contributed to some of the job losses, especially in low-wage, low-skilled (routine) occupations, and for older workers.[27] Such impacts will be felt in both manufacturing and services, and in both cases the losers are more likely to be the low-wage, low-skill intensive industries or occupations, and conversely for the winners.[28] There is also some evidence, that while increased import penetration in final goods may negatively impact on manufacturing employment, increased imports of intermediates may have the reverse effect as it is associated with increased engagement in value-chains, and consequent exports of those goods higher up the value chain.[29]

While economics tells us that there will be winners and losers from trade liberalisation, a priori we do not know how different groups (people, places, or industries) will be affected or by how much. There are various ways of conducting such evaluations. These can be broadly categorised into two strands – those that look at what has happened previously (ex post) and those that simulate what might happen following a change in policy (ex ante).

Ex post methods: (i.e. ‘after the event’) involve assessing the effects of a policy change after it has taken place – e.g. to estimate the effects of a free trade agreement once it has been in force for a period of time.

Ex post studies require data on the variables of interest before, and after, the event occurred, which can constitute data from surveys, interviews and/or official statistics. For example, information on the levels of trade before and after, the levels of trade costs and tariffs before and after, and any other factors (control variables) that the analyst considers may have impacted on trade.

There are then a range of statistical techniques, notably econometric models such as gravity models, which can be used with the aim of identifying the causal impact of the policy change, or shock. Many of the results and papers summarised in this Briefing Paper are based on this approach. For example, the paper by Amiti et al. (2019) examines the impact on prices in the US following the US administration’s introduction of ‘trade war’ tariffs. Similarly, there is a substantial literature examining how growth of international trade may impact on the wages on different categories of labour.

Ex ante methods: (i.e. ‘before the event’) encompasses tools such as Partial Equilibrium (PE) models and Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) models. These simulate the economic effects of a shock or policy change prior to it taking place, such as before a Free Trade Agreement has entered into force. The method involves taking existing data on trade, production and trade costs, and then changing the trade costs and simulating what the impact on trade and output would be from those cost changes.

Such models are normally focussed on giving an indication of the impact on different industries or sectors, as opposed to different categories of labour, or regions within countries, or different types of consumers / households. They can, however, still be used to shed light on who might be the winners and losers. For example, embedded in some models are different categories of labour (e.g. skilled vs unskilled), and the models can simulate what might happen to the demand for those different categories and what might happen to wages. Even where models do not have the labour / household / regional dimension embedded, the results on the changes in output by sector can then be used to infer what might be the impact on these categories. This requires information on labour usage by industry, or on the regional distribution of production, and /or on expenditure patterns by different household types.

Ex ante models are often used for impact assessment of trade agreements, and there are numerous studies with such assessments. Partly because of space constraints, and partly because the results are highly specific to the event being modelled we do not summarise this literature in this Briefing Paper. However, for an indication of the breadth of this work, for example with regard to the impact on the UK from leaving the EU, the interested reader is encouraged to look at Tetlow and Stojanovic (2018).

A lot of recent literature has focused on the ‘China effect’. This reflects the significant growth in Chinese sales to the US and other developed countries. The growth in exports was unexpected and rather than being primarily demand-driven, it stemmed from changes in Chinese policy (both domestic and international such as China’s accession to the WTO in 2001) and the resulting increases in productivity, and also from a distinct change in the access that the US allowed China to its market – the introduction of so-called ‘normal trading relations’.[30] The share of China in US imports was 2.6% in 1989, 8.3% in 1999, and 19.4% by 2009. For the UK the share of China was 0.43% in 1989 and 9.5% by 2009. These represent substantial changes in a short space of time.

Empirical work suggests that the impact of increased Chinese import penetration may have been directly responsible for about 10% of the US job decline in manufacturing between 1999-2011, and once linkages and multiplier effects are taken into account that figure almost doubles.[31] Detailed research on the ‘local labour market’ impacts of the China effect at the level of ‘commuting zones’ suggests that workers in the zones most exposed to import competition from China experienced considerably larger reductions in manufacturing employment and more job churning than others.[32] Lower income workers, and those with lower labour force attachment and shorter job tenure tended to see larger losses of earnings and employment. In addition, workers with less than a college qualification were more likely also to see reductions in employment in non-manufacturing industries, indicating the presence of negative local demand spillovers.

These results are largely consistent with earlier work on the local labour market impact of NAFTA on the US from increased Mexican imports,[33] and also with studies on China’s ‘local labour market’ effects in countries such as Norway, the UK, France and Germany.[34] This evidence suggests that Chinese import competition explains about 10% of the reduction in the manufacturing employment share in Norway between 1996-2007, and up to a third of the reduction in the UK manufacturing share over 2000-15. Evidence for the UK also suggests that low-paid workers were more adversely affected by Chinese import competition.[35]

An important insight from these studies is that adjustment to trade shocks can be slow, and the costs largely fall on the trade-exposed local markets rather than being dispersed nationally, resulting in persistently low local labour force participation rates and high unemployment. The slow adjustment, in turn, might be linked to longer run secular changes in the international competitiveness of industries.[36]

Having said that, losses in import-competing sectors and areas should be balanced against job gains due to increased exports. Evidence for Germany indicates that while import competing manufacturing sectors suffered job losses due to increased competition from China, this was more than offset by job gains in export-oriented manufacturing units who increased their exports primarily to Eastern Europe.[37] This is in contrast to the results discussed above for the US, and similar analysis for the UK.[38] Other evidence for the US, however, shows that within-firm reorganization and export expansion, particularly in services sectors, may serve to more than offset the job losses in import-competing manufacturing sectors.[39] Among the sectors that fared well were manufacturing industries which were more intensive users of services, in which, of course, the US has a strong advantage.[40]

While the above suggests that trade played some part in the US manufacturing job losses, evidence shows the main explanation seems to lie in increased productivity growth.[41] Technological change, and notably ‘computerization’, also helps to explain the increase in wages of skilled relative to unskilled workers in the US. Indeed, increased demand for occupations requiring computer skills are found to have contributed to roughly 80% of the rise in the skill premium, while the contribution of international trade was modest, increasing the skilled-wage premium by 2 percentage points, over 1984-2003.[42]

Further, increased import competition could also result in skill upgrading. Evidence from Belgian manufacturing firms suggests that both Chinese import competition and offshoring to China resulted in considerable within-firm skill upgrading, with Chinese import competition accounting for 27% and 48% respectively of the total observed increase in the share of non-production and highly educated workers in low-tech firms.[43]

The preceding examined changes in employment and wages across industries/sectors. However, there are also important within industry effects. Within industry effects arise because within any given industry there is substantial heterogeneity between firms, such as in terms of size and productivity. There is a very large empirical literature, which attempts to identify the links between firms and trade, and the circumstances under which firms are more likely to become ‘winners’. The evidence shows that exporting firms tend to be substantially bigger, and may become more efficient through learning from export markets and international knowledge spillovers, and from importing higher quality intermediates, economies of scale, higher levels of investment, or from increased competition in export markets.[44]

Rising productivity, which may in part be trade induced, could result in either lower or higher demand for labour by firms. This is because on the one hand it leads to lower prices and hence increased demand, but it also leads to a reduced demand for labour inputs. Evidence suggests that the latter effect has dominated.

Differences between firms rather than within firms in turn leads to considerable wage inequality within sectors and within occupations, and is partly driven by exporting firms paying higher wages than non-exporting firms. This could simply be a selection effect (i.e. that more productive firms are more likely to export and can pay higher wages), or that the act of exporting leads to more wage inequality. The evidence suggests that both factors are present and hence that trade can widen within industry inequalities.[45]

Secondly, the entry/exit of firms within an industry leads to labour market churning with both job creation and job destruction. While the net impact on employment may be small, this may conceal important labour market dynamics as the process of reallocation impacts on firm or sectoral level job losses. A high rate of labour market churning can imply greater uncertainty for workers through less job and wage security. While the literature on this is relatively small, evidence suggests that increased trade leads to more job-churning, with higher import exposure increasing job destruction, and higher exports leading to job creation. However, this does simply mean that import penetration leads to job losses, some evidence shows that cheaper imports can lead to productivity increases which in turn increases output.[46]

Trade may impact on male and female workers differently. There is some cross-country evidence that, for high-income countries, the gender wage gap tends to decrease with increased trade through a combination of a reduction in discrimination and an increase in the relative demand for female labour.[47] One explanation for this is that discrimination becomes more costly with increased competition from imports, and therefore discriminatory behaviour should be driven out with increased trade in the long run. Indeed, evidence on the gender wage gap in US manufacturing industries between 1976 and 1993 suggests that previously ‘concentrated’ industries (industries with little competition) saw larger reductions in the gender wage gap from more trade, relative to competitive industries.[48] Another aspect is that increased trade can incentivise firms to upgrade their technology to new automatic or computerized machinery, which reduces the physical requirements needed in blue-collar occupations, and increases demand for female workers.[49]

Research on the impact of increased competition from China on the US gender wage gap indicates that the gains were higher for women than for men. The driving force behind this was partly that manufacturing sectors, which were hardest hit by competition from China, were relatively more male labour intensive, and also that men faced relatively higher barriers to enter into services sectors compared to women. Combined, these factors lead to higher wage and welfare gains for women than men.[50] Conversely, and perhaps counter-intuitively, the gender wage gap could widen when trade expands sectors which are relatively more female intensive, as appears to have been the case in the US following the introduction of NAFTA.[51]

To summarise, while there is a consensus that trade generates gains overall, recent literature highlights that the impact of trade, particularly from increased competition from developing countries, has created winners and losers. Workers in sectors particularly exposed to increased import competition tend to be adversely affected through job losses and falling wages, and some evidence suggests that the impact is felt more severely by low-income workers. In contrast, sectors and firms able to take advantage of the growing export market, such as services sectors, have benefitted. Further, while consumers on the whole have benefitted from trade through lower prices and increased variety and quality of products available, evidence suggests that low-income consumers may have benefitted relatively more.

In the same way that not all individuals gain from trade, the same applies to places. There are two aspects to this. First, changes in trade impacts differentially on regions depending on which industries/sectors are located where. Second, as trade changes, this impacts on the agglomeration incentives discussed earlier, and the longer run location of industries/sectors. Each of these aspects contribute to the uneven distribution of economic activity across and within countries and also of relative incomes in different locations.[52]

However, it is hard to predict, a priori, the geographical pattern of economic activity. The impact of trade liberalisation on regional inequality depends on each region’s specific geography, on the existing structure of economic activity,[53] and on the trade-offs between trade costs and benefits from agglomeration. For example, if high tariffs are reduced for an industry which is located in a particular region, then the direct effects on that region will be larger. In the longer run one might suppose that, all else being equal, regions with better access to foreign markets may emerge as economically stronger regions, and thus that trade may deepen spatial inequalities. On the other hand, comparative advantage changes over time, and industry-region combinations which are economically strong now, may face rising competitive pressure as these changes occur.

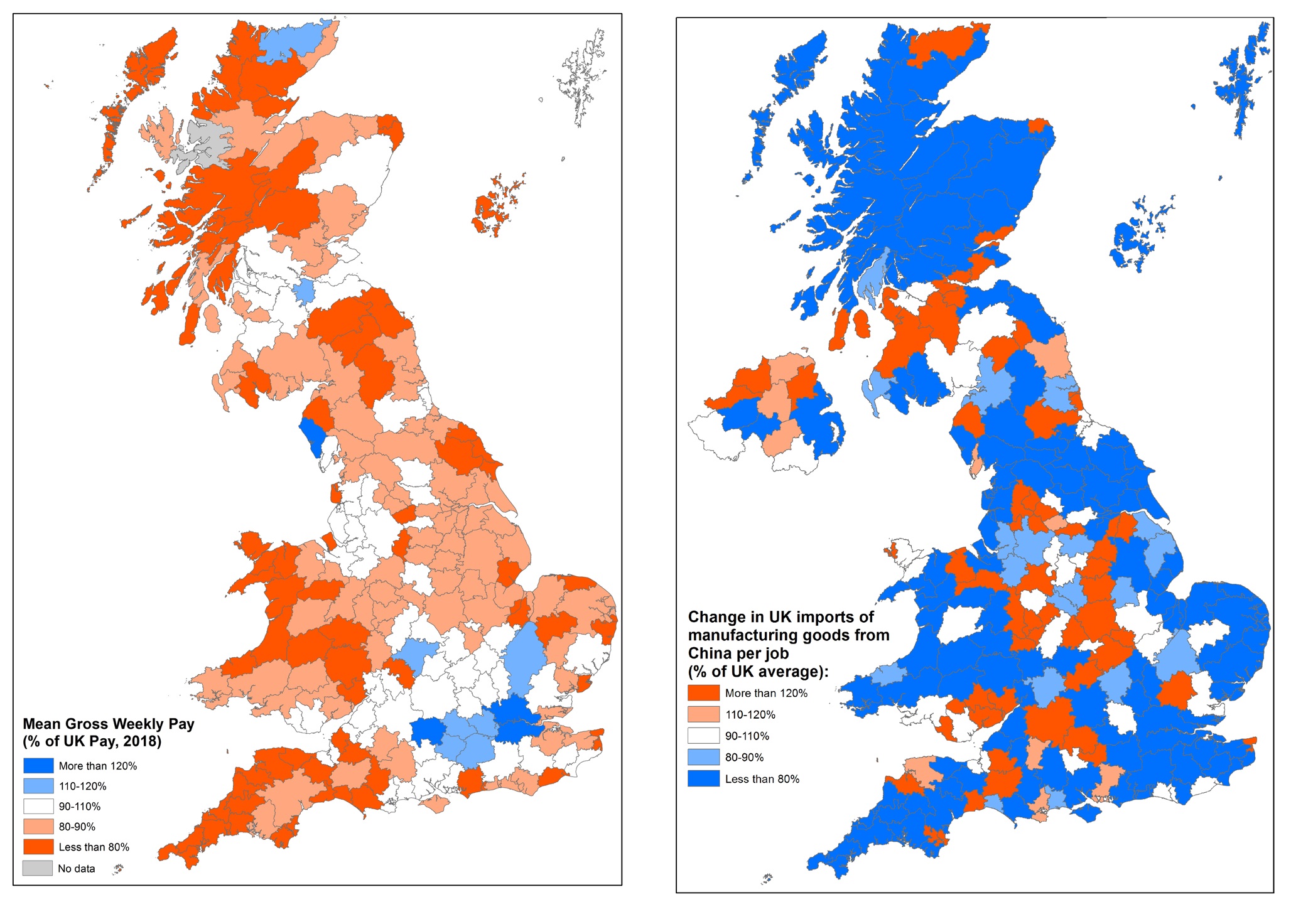

By international standards, the UK has some of the largest geographical inequalities among developed economies,[54] and some of this will have been trade-induced.[55] The geographical inequality in the UK can be seen in the left-hand map of Figure 3, which gives the distribution of the UK’s richer and poorer Travel to Work Areas (TTWAs),[56] and which shows that the poorer regions tend to be the more peripheral, such as West Wales, the South West of England, and some of Scotland.[57]

The right-hand map of Figure 3 looks at which UK regions have been most subject to import competition from China over 2000-2015.[58] Those regions with the biggest increase in import penetration are in orange, and the darker the orange the greater the increase. There is no obvious correlation between the two maps: the poorer TTWAs are not necessarily those that have been most exposed to import competition from China. For example, the South West of England is one of the poorer regions, but the impact of China per job is relatively low. So while trade impacts on the real incomes of regions, there are many other factors at play. As discussed above, the regional dispersion of any impact depends more on which import-competing industries are located where, such that we see a more substantial negative impact, for example, in the Midlands, or in Ayrshire and Lanarkshire.

The direct impacts from changes in trade or trade policy on the spatial distribution of economic activity has also been considered in other contexts. For example, recent work on the impact of US trade war tariffs has explicitly considered the regional dimension by examining which counties or states are most affected.[59] Similarly, the literature discussed earlier on the China effect also looks at which regions within countries (such as the US, France or UK) have been most exposed to import competition.[60]

Source: Map Left: Mean gross weekly pay by Travel To Work Area for all employee jobs (2018) relative to UK weekly pay (ONS, 2019); contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right, 2019. Map Right: Data are from Foliano and Riley (2017).

Cross-country studies show little evidence that trade liberalisation leads to a concentration of economic activity or regional inequality. In contrast, within-country studies suggest a greater degree of trade-induced regional economic divergence. The evidence suggests that proximity to the rest of Europe had some impact on the spatial distribution of UK manufacturing following accession to the European Economic Community (EEC), with more activity relocating towards ports in the South East.[61] The opposite was observed when East and West Germany were split.[62] West German cities close to the new border performed worse than other cities in West Germany because they lost half their traditional markets: they went from being at the centre of an integrated Germany to being on the periphery of West Germany. Border effects have also been examined for the trade liberalisation between Mexico and the US, with Mexican economic activity shifting towards the border.[63]

Direct evidence on trade and spillover effects, such as those discussed earlier, is harder to find although, for example, there is some evidence that where exporting requires specialised knowledge of foreign markets and contacts abroad, such information asymmetries may incentivise exporters to agglomerate in order to make information-pooling easier.[64]

Interesting also is the presence of regional multiplier effects. There is evidence that tradable sectors and exporters pay higher wages and the expansion of exports leads to the creation of jobs in other non-tradeable sectors, through a ‘local employment multiplier effect’.[65] Evidence for the US suggests that, on average, for every 10 manufacturing jobs created in a US city there are 16 additional jobs created in the wider economy. In the ‘innovation sector’ the multiplier effect may be much bigger with up to 40-50 additional jobs. Related work for the UK suggests much smaller multipliers where, for every 10 jobs created in advanced industries, a further 6 jobs are created in the wider economy.[66]

From the previous discussion it is clear that the impact of trade on an economy, and on winners and losers, is complex. The losers from international trade tend primarily to be the firms, the workers within those firms, and the places the firms are located in, that are directly affected by increased import competition from abroad. Conversely, the winners are consumers and users of imported intermediate goods, and also the firms, workers, and locations associated more with exporting activity. The losers tend to be fewer and more concentrated, while there are typically many more winners but more widely dispersed. The impacts are complex, and in turn it means that there are no easy policy prescriptions. Indeed, while it has been recognised that countries’ ability to realise the full potential gains from trade depends, at least partly, on the accompanying supporting policies,[67] it is also true that there is no one-size-fits-all policy strategy to achieve this.[68]

Generally, there are two principal justifications for policy intervention: market failure and equity. If markets are in some way imperfect they will not generate the most efficient outcomes, and there may be scope for governments to intervene to address those ‘market failures’. For example, if firms lack knowledge about export opportunities abroad, or about the procedures required to access particular markets, then government action might be able to address these information and coordination problems. Second, even if markets are working well, societies may be concerned about the distributional implications, and hence desire intervention to ensure the gains from trade are spread more equally. That is the role of a progressive taxation system, which in turn funds social security and labour market adjustment programs.

However, it is important to note that getting government intervention right is tricky: governments may lack sufficient information, may be subject to capture by interest groups, and may lack policy flexibility in various dimensions (time, place, sector). Bad policy can create further distortions and problems. In addition, policy in response to trade, is not necessarily the same thing as trade policy. Trade policy is inherently concerned with (economic) relations with other countries – be this tariffs, quotas or regulatory requirements.

This section looks in more detail at some of the policy responses that could potentially help losers from international trade adjust, and ensure that the winners can take advantage of the new opportunities created by trade liberalisation.

Firms: Negative impacts on firms could arise from long run changes in competitiveness (e.g. the decline of textiles, or iron and steel industries in the UK); from within-industry competitive pressure even in apparently competitive industries (e.g. Honda closing its Swindon plant); or from sudden import surges which could be the result of other countries’ trade practices or trade sanctions (such as with US trade war tariffs).

The appropriate policy responses will depend on the underlying causes and industrial structure. If the cause of the disruption derives from clearly identifiable unfair trade practices or unexpected import surges, there may be an argument for use of trade defence instruments (e.g. anti-dumping, countervailing or safeguard duties). However, first, identifying what constitutes an ‘unfair’ trade practice can be difficult, and the use of anti-dumping duties, for example, is complex and contentious in the World Trade Organisation. Second, such instruments can be misused and may not even be well targeted to help the negatively impacted industries. Third, in a world of integrated supply chains governments should be careful to ensure that policy interventions do not disrupt those supply chains. Finally, such policies favour producer interests, often at the expense of consumers who have gained from cheaper imports. Hence, even if there are unexpected import surges or evidence of unfair trade practices, the use of trade remedies may not be the best response.

If the underlying cause is a longer-run secular decline in competitiveness, such as the example of the UK car industry in the early 1980s given earlier, then policy might be more focussed on adjustment assistance, fostering the growth of alternative activities, or policies to increase productivity and reinvigorating competitiveness. In other circumstances, policy might focus on longer-run support for investment, finance, or research and development. This may be sector-specific but the necessary precursors to such interventions should be an assessment of the long-run competitiveness and viability of the industry concerned, and a good understanding of why the private sector is not responding sufficiently. Modern thinking about industrial policy has focussed more on facilitating particular activities and tasks regardless of sector, and allowing market forces to determine where these are taken up. Thus, for example, government might seek to facilitate the acquisition of skills through education or communications by providing modern infrastructure.

Workers: Labour markets experience shocks for various reasons such as changes in technology and/or changes in demand, some of which have little to do with trade. While changes in trade appear to have had a bigger negative impact on lower-skilled workers, other factors such as changes in technology have played an important role. Most governments have various labour market safety net policies, such as social insurance or re-training. It is not obvious that there should be a different set of policies for trade-induced shocks to wages and/or employment because these are, in many ways, the same as other labour market shocks and separating them in order to determine eligibility for policy-support is a major analytical challenge.

However, where trade induced shocks are substantial (e.g. the China effect) and identifiable, there may be a case for specific trade related adjustment assistance programs. Indeed, several countries already have these types of programmes in place, such as the Trade Adjustment Assistance programme in the US and the European Globalisation Adjustment Fund. In practice evidence suggests these programmes can be difficult for workers to access and are often under-utilised.[69] Recent work on the US suggests that trade adjustment assistance did have a positive impact on workers, both in terms of how quickly workers became re-employed, and also in terms of higher incomes, with a bigger impact in the more disrupted regions.[70] What is less clear is the extent to which it is unemployment insurance, retraining, or relocation assistance which results in these outcomes. It appears however, that successful adjustment assistance programs need to be easily accessible, flexible and encourage retraining and re-entry into labour markets as well as labour mobility.[71]

The preceding in turn raises the question, and difficulty, of identifying what constitutes a trade-induced shock and how to identify its impact. Additionally, in the future there may be more significant disruptions for workers driven by (in part trade-related) changes in technology and automation.[72] This will affect what is traded, by whom and where and so may call for adjustment assistance.

Places: As already discussed many factors influence regional inequality and trade is one such factor. However, evidence shows that firms and individuals in regions with high concentrations of import-competing industries are more likely to be negatively impacted by policies that increase trade. One of the clear results from the empirical literature is that negative shocks can be long lasting (i.e. the East German regions still lagging behind the West German regions) and it may take a long time for localities and regions to adjust to such shocks. This in turn can lead to negative spillover effects for example on crime, health and schooling. This suggests that governments may need to mitigate the speed of market opening, for example by phasing in new trade agreements over a number of years, in order to reduce the shock to the local economy and give it time to adjust. It may also require policies to improve the attractiveness of ‘disadvantaged’ regions, be this through improvements in infrastructure, through fiscal incentives, or through improving (re)training opportunities in those regions.

Most trade-oriented policy focuses on exports and hence on helping firms (and by extension the workers within those firms) to become winners from trade.[73] To the extent that trade leads to higher productivity (as opposed to simply the more productive firms exporting), and to the extent that there are market failures which prevent firms from exporting, there may be grounds for government intervention.

The grounds for such intervention may be that firms have imperfect information (e.g. on sales or investment opportunities in foreign markets, on investment opportunities for foreign firms in the domestic market, or on policy and the business practices in those markets); that there may be spillovers between firms; the existence of institutional or procedural entry barriers, and possibly ad hoc discriminatory policies; or finally just to provide more certainty for firms (for example as a guarantee of stable political relations with a trade partner).

Such interventions could take various forms, ranging from direct assistance to firms, interventions with host government/officials, or to broader policy steps such as signing or negotiating Free Trade Agreements, raising issues in the WTO, or conditionality linked more broadly to economic diplomacy.

Trade policy can (and should) also form part of a broader industrial strategy. Economies evolve and governments have an important role in guiding and responding to that evolution and in considering how policy can be appropriately used to facilitate and even nudge trade in a given direction. Conceptually, this is consistent with the UK Government’s ‘sector deals’ which form part of its Industrial Strategy, but in practice this will depend on the actual form that policy takes because there are some risks involved.[74] Governments typically have a bad record in identifying firms which are likely to be successful, or indeed industries which are likely to be successful. What is important, therefore, is to provide an environment (information, long-run incentives, financing) which make it easier for firms/industries to be more successful in the longer term. In good part, this also involves understanding the conditions and constraints under which firms operate, and what those conditions and constraints are in comparison to competitors abroad.

International trade has grown significantly over the last century as countries have become more integrated, and as cross-border shipping of goods and providing of services have become easier and cheaper.

Most economists have argued – rightly so – that, overall, growing international trade has benefitted countries, and within them consumers, workers, and businesses. International trade leads to greater specialisation and more efficient resource allocation, and this often leads to lower prices, more output, and improvements in productivity.

However, increased competitive pressures also result in industries and sectors declining, less efficient firms closing down and workers being made redundant. Such losses from trade are typically much more concentrated than the gains, which has fed concerns about the perceived disproportionate impact from trade, and globalisation more widely.

For example, the literature examining the rapid rise of Chinese trade, suggests that increased Chinese import penetration may have been responsible for about 1 million out of the roughly 6 million job losses in US manufacturing between 1999 and 2011. On the other hand, increased US exports over the period are believed to have increased employment in other sectors, such as services, by even more. It is important, therefore, to understand who gains and who loses, by how much, and under what circumstances.

The wider evidence for developed countries suggests that low-income consumers benefit more from trade-induced lower prices than do high-income consumers because a higher share of their income is spent on traded goods. At the same time, if we take people as workers, those in high-skill/high-wage occupations may have gained more than the less-skilled. This is because the latter face more significant import competition from developing countries, and their inputs may be easier to replace and/or offshore.

While some less efficient firms in import-competing industries may be crowded out of the market, increased export opportunities may bring significant benefits to firms that successfully export as they increase their productivity and their international competitiveness. This will tend also benefit the workers within those firms.

In the same way that not all people and firms benefit from trade, the same applies to places. The mechanisms which impact on regional economic activity involve complex trade-offs between the positive forces for agglomeration and the costs of moving goods, people and knowledge. The literature is inconclusive as to whether trade liberalisation leads to growing or declining regional inequalities. This depends on the specific geography of each country and the regions within it, as well as existing economic, physical and institutional structures.

In this context, making good (trade) policy is complicated. It involves complex trade-offs between, for example, different groups, different places and different time-scales, as well as the targeting of scarce public resources. For example, in the short run one may wish to relax international competitive pressures to ease adjustment and address distributional concerns. On the other hand, long-run prosperity requires that adjustment towards more competitive and higher growth sectors occurs. This may be fostered by policies to address the factors that hinder the development of new activities and at times may also call for policy focussed on specific sectors. Policy also needs to address the skills and training for those needed in the emerging sectors, as well as the adjustment assistance and retraining needs of those negatively affected and at risk of being marginalised. The consequences of trade policies are also hard to predict. This suggests that we should place less faith in tailoring them precisely to a set of objectives than to keeping them simple and robust and recognising that sometimes countervailing policies are required to share the gains from trade fairly. We leave all these discussions for a later occasion.

[1] See, for example, Helpman (2016) for a discussion of the rise in inequality in developed countries since the mid-1970s and for a review of the impact of trade on inequality.

[2] See, for example, Feigenbaum and Hall (2015), or Jensen et al. (2016).

[3] This Briefing Paper is based on a review of existing literature. We have tried to minimise detailed referencing. The interested reader can find the accompanying full bibliography on our website.

[4] Motor cars defined by the SITC 3-digit code 732; medicines and pharmaceutical products by ISIC code 541; clothing by ISIC 841. Source: UN Comtrade

[5] Aircrafts defined by the SITC 3-digit code 734 and power generating machinery by ISIC code 711. Source: UN Comtrade

[6] It is possible that the net effects of an act of trade liberalisation are negative, but the evidence suggests that this is rare.

[7] This is the principle of comparative advantage, which arises when there are differences in relative costs across countries.

[8] This is sometimes referred to as ‘allocative efficiency’.

[9] See Wagner (2012) for a review of the evidence on the impact of trade on firm performance; Silva et.al (2012) for a discussion of learning by exporting, and Burstein and Melitz (2013) or Aw et.al. (2011) and Bilir and Morales (2016) for a discussion of the relationship between trade and innovation, and Klenow and Rodríguez-Clare (2005) on impact of externalities on growth.

[10] This is sometimes referred to as the ‘new economic geography’. See for example, Fujita et.al. (2001) and Gardiner et al. (2012).

[11] See Perkins and Tang (2017) for a discussion of Korea.

[12] See for example Amiti et al. (2019) on the impact of US trade war tariffs on consumer prices and varieties and Fajgelbaum et al. (2019) on regional impacts of the trade war tariffs.

[13] See Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal (2016), Table IV, p.1150

[14] Francois et.al. (2007)

[15] Breinlich et.al (2016). See also Berlingieri et al. (2018) for a related study of the impact of EU trade agreements on a wider number of EU countries.

[16] Broda and Weinstein (2006). See also Hsieh et al. (2016) on consumer welfare effects in Canada from the Canada-US FTA, who find welfare gains overall from lower consumer prices but argue that any variety gains from imports are more than offset by variety losses from domestic firms exiting the Canadian market.

[17] Amiti et al. (2019)

[18] In this they build on Feenstra and Weinstein (2017) who suggest that competitive disciplines is an important source of the gains from trade as well as of their distribution.

[19] Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal (2016)

[20] OECD Economic Outlook (2017)

[21] OECD Employment Outlook (2017)

[22] See Lawrence and Slaughter (1993), Krugman and Lawrence (1994), Katz and Murphy (1992) for the former position and Sachs and Schatz (1994) and Borjas et.al (1992) for the latter.

[23] See for example Wood (1994).

[24] Swiecki (2017), OECD (2017).

[25] Autor (2018)

[26] Similarly UK manufacturing employment fell by 2.8 million over the period 1982-2018. See: House of Commons Briefing Paper (2018)

[27] Ebenstein et al. (2009).

[28] Jensen and Kletzer (2008) discuss this in the context of the US. See Görg (2011) for a broader discussion and review of slightly earlier empirical evidence.

[29] OECD (2017)

[30] Pierce and Schott (2016)

[31] Acemoglu et al. (2014)

[32] Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013, 2016); Autor, Dorn, Hanson, Song (2014)

[33] Hakobyan and Mclaren (2016)

[34] See Balsvik et al. (2015) on Norway; Foliano and Riley (2017) for the UK; Dauth et.al (2014) on Germany, and Malgouyres (2017) who looked at France.

[35] Pessoa (2016)

[36] See Eriksson et al. (2019) who link this to the product cycle underlying each good, and how competitiveness changes over the course of the product cycle.

[37] Dauth et.al. (2014)

[38] See Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013, 2016) for the US, Foliano and Riley (2017) does not find evidence that accounting for exports to China or Eastern Europe makes a significant difference to their results for the UK.o

[39] Feenstra et al. (2018), Dauth et.al. (2014), Magyari (2017)

[40] Bamieh et al. (2017)

[41] Devaraj and Hicks (2015)

[42] Burstein, Morales and Vogel (2016)

[43] Mion and Zhu (2013)

[44] See Greenaway and Kneller (2007), Wagner (2007, 2012), Redding (2010), and Silva et al. (2012), for reviews of the empirical literature.

[45] For early work on this see Bernard and Jensen (1995) who find that exporters are on average larger, more productive, more capital intensive and pay higher wages: exporting plants pay wages that are more than 14% higher than those paid by non-exporting plants. For more recent work see Akerman et.al, (2013), and Helpman et.al. (2017) provide evidence for Sweden and Brazil respectively, and Egger et.al (2013) analyse five European economies.

[46] Davidson and Matusz (2005), on the US and Canada, Kim and Sun (2009), Autor (2013b) as part of the China effect, Lo Turco et al. (2013) on Italy. See also Görg (2011).

[47] Oostendorp (2009)

[48] Black and Brainerd (2004)

[49] Juhn et.al (2014)

[50] Brussevich (2018)

[51] Sauré and Zoabi (2014)

[52] European Commission (2017) Reflection Paper on Harnessing Globalisation.

[53] See Brülhart (2011), or Rodríguez-Pose (2012)

[54] Carter and Swinney (2019)

[55] Foliano and Riley (2017)

[56] Unlike formal administrative boundaries such as counties, TTWAs aim to capture geographic areas where people both work and live. For a fuller definition, see: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/articles/traveltoworkareaanalysisingreatbritain/2016#definition-of-2011-ttwas

[57] The comparison is based on the mean weekly wages in a Travel to Work Area relative to the UK average weekly wage.

[58] We gratefully acknowledge Foliano and Riley (2017), who supplied us with the underlying data to enable us to replicate their map which appeared on p.9 of their article.

[59] See Fajgelbaum et.al (2019).

[60] See for example Autor et.al. (2013, 2016) for US, Malgouyres (2017) for France and Foliano and Riley (2017) for UK.

[61] Overman and Winters (2005, 2006)

[62] Redding and Sturm (2008)

[63] Seven out of 14 within-country studies of spatial effects of trade openness look at Mexico. Among them Hanson (1997, 1998) focusses on border effects and shows that trade liberalisation led to a shift of activity towards the Mexican border with the United States; these border regions were already richer and more industrialised than the national average leading to spatial divergence.

[64] Lovely et al. (2005). See also Ellison et.al (2010) who consider the forces for agglomeration in the US, in a non-trade context.

[65] See Moretti (2010)

[66] Clarke and Lee (2017).

[67] See Newfarrmer and Sztajerowska (OECD) (2012)

[68] See IMF (2017) for a discussion on policies to facilitate adjustment to trade.

[69] See for example Cernat and Mustilli (2017) on the European Globalisation Adjustment Fund and Autor (2018) on Trade Adjustment Assistance programme.

[70] See Hyman (2018) who finds a positive impact. In comparison D’Amico and Schochet (2012) suggest that the impact of trade adjustment assistance was minimal, although they recognise difficulties in their data which makes identification more difficult.

[71] Autor (2018)

[72] Baldwin (2019)

[73] This can be seen from the UK Government’s Export Strategy published in August 2018, and also in an earlier 2011 paper published by the then Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, entitled International Trade and Investment – the Economic Rationale for Government Support.

[74] Currently the UK Government has sector deals with 6 sectors: Artificial Intelligence, Automotives, Construction, Creative Industries, Life Sciences, and the Nuclear Sector.