2. Rationales for Official Export Credit Agencies – and for their Regulation

3. UKEF and International Competitiveness

3.1 Utilizing Flexibilities under the OECD Arrangement

3.2 OECD Arrangement Participants use of Non-Arrangement Covered Export Credit Support

3.3. Non-OECD Participants’ Export Credit Support

4. Regulatory Shifts in Official Export Credit Support Control

The first export credit agency (ECA) established in the world, the UK Export Finance (UKEF) is one hundred years old this year.[1] The UKEF’s stated mission is “to ensure that no viable UK export fails for lack of finance or insurance, while operating at no net cost to the taxpayer”.[2] Since the 2016 Brexit Referendum, the strategic importance of increasing UK exports to outside of the EU has been further heightened in the pursuit of new sources of future national growth.[3] With this aim, the UK Government has put renewed priority on developing the UKEF as a vital component of its new export strategy.

The difficulty is that the UKEF needs more export business to support; it has committed only £22bn of the available £50bn headroom.[4] UKEF increased its net operating income for the year ended 31 March 2019 to £128m.[5] This is up from £5 million for the year ended 31 March 2018, but still comparable with year ended 31 March 2015.[6] While the Commonwealth has been earmarked for renewed incentives to promote trade and investment, in 2017 only 7% of UK’s exports went to the ten largest Commonwealth markets, as compared with 42% to the EU.[7]

Yet securing new export opportunities to support is increasingly challenging in the current trading environment of global export stagnation.[8] From being the first ECA, the UKEF is now just one of over 110 ECAs operating to promote their domestic exporters. Together they provided approximately US$211 billion in total trade-related medium-to-long term (MLT) official export credit support in 2017.[9] With so many ECAs seeking to promote their domestic exporters, there is a real risk of an export credit race in which exporters compete on the basis of being granted the most favourable financing terms from their respective governments, rather than on the price or quality of the goods or services themselves. The terms of the support a foreign buyer can obtain from an ECA have become an increasingly important factor in its choice among different exporters.

So, although export credit support is seen as the fuel that powers the international trading system,[10] in competing for overseas contracts there is a potential for governments to use public resources to provide unfair subsidies to exporting firms in the form of export financing. This has been termed corporate welfare and simply “pads the profits of politically connected corporations on the taxpayer’s dime.”[11] That is, while export credit subsidies can be used to address market failures in international financing, they can also be used as general export-subsidizing instruments. They can divert business away from more efficient competitors, as well as trigger subsidies wars in which exporting nations waste resources competing with each other to confer a competitive advantage on exporters.[12] Indeed, ‘among the various forms of export subsidies, subsidized export credits arguably have the most immediate effect and thus greatest potential to distort trade flows.’[13]

Numerous policymakers and commentators have decried the potential economic distortions associated with government subsidies, including those implemented through export financing.[14] As a result, a range of legal disciplines on subsidies have evolved. At a ‘club’ level, the 1979 OECD “Arrangement” on Officially Supported Export Credits is a specialised instrument regulating the activities of ECAs. The OECD Arrangement seeks to create a level playing field among its Participants. Its objective is to encourage fair competition between exporters goods and services, rather than on the basis of more favourable support from their governments.[15] At the multilateral level, the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM) provides a binding framework for controlling export subsidies. Under the WTO SCM, export credit support is deemed to be a subsidy if it confers upon the foreign buyer an export credit at terms not available on the commercial market.

This Briefing Paper examines the export credit support options open to UKEF, with specific reference to its international legal obligations under the OECD and the WTO. Leaving the EU will not change the UK’s obligations under either, but the UK Government will make and defend its position towards official export credit support as a single country, rather than within a bloc. The options open for the UK raise compliance questions. In addressing these issues, this paper is set out as follows: It first examines the rationale for official export credit support, and the rationale for regulating any such public support. The paper then focuses on the UK ECA – the UKEF – from within the current international market for official export credit support which increasingly includes non-OECD Arrangement type programmes from its Participants, as well as more active ECAs that are not participants of the OECD Arrangement. This development has detracted from the role of the OECD Arrangement, and places more pressure on the WTO system to regulate official export credit support. However, the SCM does not provide the necessary specialised instruments for regulating export credit subsidies, and the need for stronger regulation comes at a time when the WTO system is already under strain.

ECAs are fundamentally mercantilist in nature – they seek to promote domestic exports to secure employment and create national wealth. Yet despite such economic nationalism, ECAs are seen to be legitimate and even encouraged, particularly during financial crises. This is because ECAs can address market failures or information asymmetries in the private export financing market. For some commentators, official export financing support can ameliorate distortions in domestic and international markets and may represent the best policy instrument for addressing distortions to the degree that they operate directly on the distorted margin.[16] More specifically, through ECAs, governments can offer support for export transactions not readily offered by the private sector either through lack of availability, or because the private capital market lacks sufficient information to properly assess the risks of the transaction. Governments on the other hand, are better positioned to access the necessary information to assess the risks of the transaction.[17]

Others argue that unbridled and competing national subsidies can undermine world prosperity and require regulation.[18] Indeed, competition among ECAs to offer their exporters the best support has significant budgetary implications and, by cancelling out other offers, could result in a zero-sum game. Moreover, no government can unilaterally decide to stop subsidizing export credits without its exporters losing sales. As such, preventing a subsidy war through export credit support requires international cooperation. Accordingly, a range of organizations and legal instruments have been developed over the past 60 years to provide a wider rules-based system for a more orderly market for export subsidies, including official export credit support.[19]

The OECD Arrangement is the most specialised legal instrument for controlling official export credit support. The Arrangement provides substantive conditions requiring that forms of officially supported export credits are subject to repayment requirements. Such support can take the form either of “official financing support”, such as direct credits to foreign buyers, refinancing or interest-rate support, or of “pure cover support”, such as export credits insurance or guarantee cover for credits provided by private financial institutions. The Arrangement’s Participants offering official financing support for fixed-rate loans through direct credits or interest rate support mechanisms must apply the relevant Commercial Interest Reference Rate (CIRR) as the minimum interest rate.[20] However, Participants are allowed to provide “pure cover” to export credits extended by private actors with interest rates that may be below the CIRR. OECD Arrangement Participants are also obliged under the Knaepen Package, to charge premia to cover the risk of non-payment of export credits, which must be risk-based and adequate to cover long-term operating costs and losses. Alongside setting out the financial conditions for export credit support, the OECD Revised Council Recommendation on Common Approaches on the Environment and Officially Supported Export Credits (the OECD Common Approaches) further requires OECD Participants’ ECAs to address anti-bribery, environmental, social and human rights (ESHR) impacts, and sustainable lending to heavily indebted poor countries, when they support exports through the provision of export credits.

The OECD Arrangement and Common Approaches are soft law instruments that do not create enforceable rights and duties.[21] Yet despite weak enforcement, the soft law approach has hitherto played a positive role within international negotiations between diverse parties seeking to respond to complex cross border export credit support issues that challenge domestic sovereignty.[22] The OECD Arrangement has been a rational choice for governments – but only as long as the benefits of deterring violations exceeds the costs of the expected loss from any violations. The Arrangement emerged as the most sensible option in an area where there was uncertainty about the appropriateness of hard rules on export credit activities due to unknown future circumstances. It provided the governments and industries of the major ECA countries with the essential knowledge and security that competition was based on the quality of products and services. Moreover, by incorporation into the WTO SCM through implicit reference (See Section 4), those ECAs following the Arrangement’s terms and conditions have been provided with a safe harbour from the WTO’s general prohibition on export subsidies.

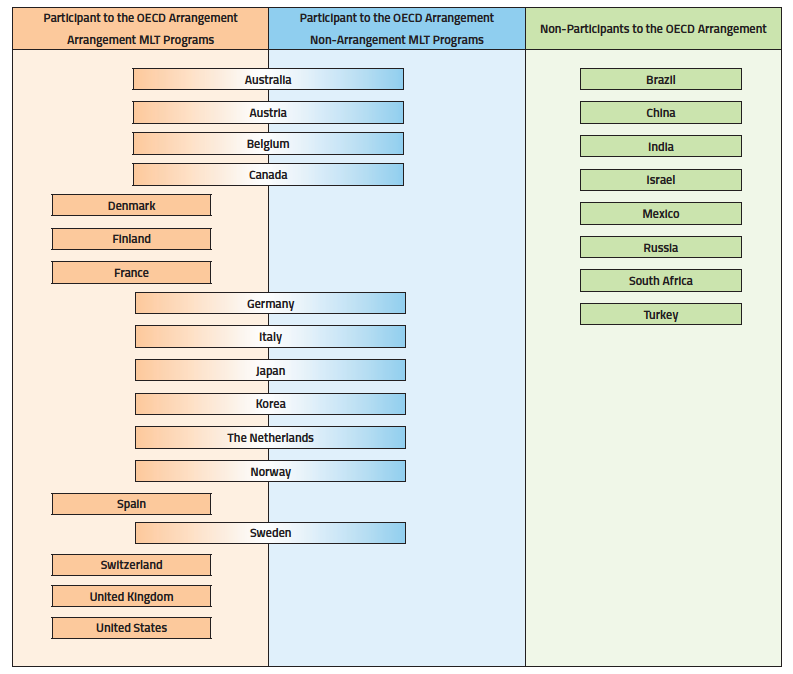

However, the OECD Arrangement is increasingly suffering from its limited membership. As of 2019, the 35 participants to the Arrangement include: Australia, Canada, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, the United States, the United Kingdom and all other the EU Member States except for The Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary, who are observers. Membership is only by invitation from the current Participants. New players in export financing such as China, India, Brazil[23] and Turkey, are not members and therefore do not have to abide by these guidelines. Moreover, while the Arrangement offers some flexibilities for its Participants to adapt more competitive programmes, export credit support mechanisms that lie outside of the OECD Arrangement’s scope have started to emerge. Consequently, the OECD Arrangement’s influence over export credit agencies is shrinking in relative terms, both geographically and in substance, just at a time when governments are increasingly seeking to spur domestic growth through exports.

The evolution of export credit support has implications for UKEF’s competitiveness as well as its compliance with its international obligations. The following sections look more closely at these developments.

The UKEF is competing to support UK exporters overseas activities within an export credit industry that has been undergoing a fundamental change. Traditionally, a public ECA was perceived to be the lender of last resort, operating only in cases of market failure, caused by a lack of resources or commercial appetite in the private financial sector. Indeed, as commercial financial markets became more robust in the 1990s, it was thought that the role and significance of ECAs would suffer a commensurate decline. However, after the onset of the 2007 financial crisis, ECAs were brought centre stage, once more as lenders of last resort. Official export credit support became critical to ensuring liquidity in the international trading system, as commercial banks retreated as funders and risk takers of medium and long-term export finance. Since then, ECAs have been redefining their activities as a crucial element of a strategic big picture of governments’ industrial policies.

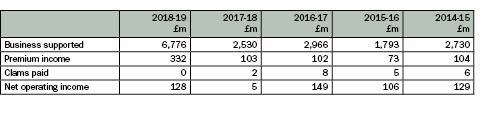

In the UK, the government is introducing new types of export financing via UKEF to provide the maximum available for commitments.[24] Yet Table 1’s Financial Overview of UKEF indicates that the value of business supported and premium between 2014-2018 was fairly static but both increased significantly over the past year 2018-2019 after a dramatic drop in 2017-2018. This is a positive signal that UKEF is succeeding in a challenging environment. Particularly given that since the Brexit referendum, the sterling depreciation that was expected by some to spark an export boom has not translated into faster-growing values of overall exports from the UK.[25]

Table 1 Financial Overview – 5 Year Summary[26]

One challenge to maintaining this increased business support is that against a backdrop of decreasing global exports, there is also increasing export finance emanating from the emerging economies. As a result, the UKEF is now competing not only against other OECD Arrangement Participants’ ECAs but also with newer ECAs in emerging economies that are not Participants to the OECD Arrangement. Moreover, rather than operating from a lender of last resort rationale or from a market failure rationale, ECAs are also increasingly competing with the private sector.

One challenge to maintaining this increased business support is that against a backdrop of decreasing global exports, there is also increasing export finance emanating from the emerging economies. As a result, the UKEF is now competing not only against other OECD Arrangement Participants’ ECAs but also with newer ECAs in emerging economies that are not Participants to the OECD Arrangement. Moreover, rather than operating from a lender of last resort rationale or from a market failure rationale, ECAs are also increasingly competing with the private sector.

Table 2 sets out the value of the 10 most active ECAs in 2017. The two largest providers, China and India, are not Participants to the OECD Arrangement. China was the world’s largest provider of Medium-Long Term (MLT) export credits at $36.3 billion—one-third the global MLT export credit total. China outstrips the value of export support provided by EU Member States’ ECAs by at least four times. By 2017, Chinese trade-related ECA activity had risen above the OECD Arrangement covered activity.[27] The absence of the US from this list is because for the past three years the EXIM board was without the necessary quorum of three members and unable to authorize transactions greater than $10 million.[28] In May 2019, the US Senate confirmed three new Members of the EXIM board, but EXIM’s authorisation expires on September 30th 2019. If Congress reauthorises the EXIM Bank,[29] it will further add to the competition among ECAs offering overseas business support.

Table 2: Top 10 ECA providers 2017[30]

| Country | Billion US$ | |

| 1 | China | 36.3 |

| 2 | India | 9.7 |

| 3 | Italy | 8.9 |

| 4 | Korea | 7.9 |

| 5 | Germany | 7.0 |

| 6 | France | 6.8 |

| 7 | Finland | 5.5 |

| 8 | Belgium | 3.1 |

| 9 | Netherlands | 2.4 |

| 10 | United Kingdom | 2.1 |

In response to greater competition, the UKEF, along with the other Participants to the OECD Arrangement, is recalibrating its export credit support programmes to better meet the needs of their exporters. Under the OECD Arrangement, Participants may finance up to 85% of an export contract’s value regardless of the level of domestic content that contract contains.[31] Subject to this rule, Participant ECAs are free to implement a foreign content policy that supports its own domestic economy. This flexibility under the OECD Arrangement has led to significant variation. Content requirements are one of the primary areas of flexibility that Participants’ ECAs can use to support national champions and to help internationalize domestic suppliers. Aggressive content policies give ECAs the ability to help pull sourcing to their own countries in sectors of strategic interest.

ECAs operating under the Arrangement have two content-related policies they can adjust to maximize flexibility. First, they can lower the minimum domestic content an export contract must contain in order to qualify for support. For example, in the UK, in all credit contracts, the maximum level of support for all Foreign Content is 80% of the contract value, thus requiring a minimum 20% UK content.[32] The US EXIM bank content policy, on the other hand, will support the lesser of either 85% of the value of goods or services within the US export contract, or of 100% of the US-produced or US-originated content within the U.S. export contract.[33] Second, ECAs operating under the Arrangement are also free to determine what qualifies as eligible domestic content. Some Participant ECAs use a content policy based on perceived national interest or value-creation. These are broader concepts than, for example, the US EXIM’s content policy, which uses domestic content as a proxy for U.S. jobs. In contrast, in using national interest or value-creation concepts other factors are considered, such as overall company exports, research and development, dividends and royalties associated with a given transaction, or an evaluation of how a given transaction will contribute to the long-term competitiveness of a national champion. A broader concept clearly offers a more flexible approach towards their transactional assessment for export support.

To take advantage of these Arrangement flexibilities, following consultations in 2019, the UK Government has introduced a principled approach to provide UKEF further flexibility in foreign content.[34] The maximum level of support for all foreign content remains 80% of the contract value, thus requiring a minimum 20% UK Content. However, the proportions of foreign content to UK content will apply to the value of UKEF’s support of a contract or a project which may consist of multiple contracts under a single supply chain, in addition to the traditional one-buyer/one-supplier/one-contract model. UKEF could consider the amount of UK content contained within related (but not directly financed or supported) contracts or projects when forming a view about a specific contract or provide support for a share of a contract where there is a specified amount of UK content.[35] This would facilitate the aggregation of UK content relative to a financing tranche. Additionally, UKEF may provide support if it can be demonstrated that the proposal is conducive to supporting or developing UK exports. Examples of this could include increasing future production in the UK, increasing the value or proportion of spend in the UK supply chain in the future, or increasing the number of jobs created in the UK in the future. [36]

UKEF has also utilized the flexibilities available under the OECD Arrangement to expand its risk appetite. Participants to the OECD Arrangement are required to charge a minimum premium for all relevant transactions based on two risk-related factors: a country rating, which is standardized; and a buyer rating, where the discretion is given to ECAs. In the case of the latter rating, there is significant inter-ECA variation in the assignment of buyer-risk ratings for the same buyer in the same country in a given year. A two-notch difference in risk rating can correspond to differences in up-front exposure fee pricing of more than 1.5%. Remaining in line with the Arrangement, UKEF has grown its risk appetite, doubling its maximum exposure limits from £2.5 billion ($3.4 billion) to £5.0 billion ($6.8 billion).[37] This change was supplemented by an expansion in the types of programmes UKEF offered in 2016, including its first long-term direct lending, euro-denominated loan for a gas-fired power plant in Turkey. This supported roughly €23 million in British exports. Additionally, UKEF expanded the number of local currencies in which it can provide support.[38]

However, the UKEF is not alone in re-designing its activities to take advantage of these flexibilities under the Arrangement. For example, in 2017, SACE in Italy agreed to fully provide support to buyers of Boeing 787 aircraft, despite the Boeing 787 only containing approximately 14% Italian content.[39] The government of France transferred its guarantee from COFACE, a private insurer, to Bpifrance, which is a government bank, in December 2016. Bpifrance now offers a direct state guarantee as opposed to COFACE’s guarantee on behalf of the French state. This enhances France’s export credit support, making it more accessible to commercial banks in the context of a challenging regulatory regime because it circumvents the capital adequacy rules applicable to commercial banks. Under the Basel III standards, commercial banks such as COFACE need to hold additional capital and to undertake initiatives to address maturity mismatches between their assets and liabilities. In Germany, Euler Hermes has increased its political and commercial risk coverage to the OECD Arrangement maximums of 100%. Germany has also made its content policy more streamlined and flexible, now allowing 49% foreign content for all transactions (including local costs) with room to negotiate the percentage even higher on a case-by-case basis.[40]

The UKEF also faces a rapid expansion of trade-related export support programmes that fall outside the scope of the OECD Arrangement rules altogether. These new mechanisms include most notably investment insurance and market window-arrangements. OECD mid-to-long term (MLT) activity was approximately $66 billion in 2016, down 15% compared with the year prior.[41] This fall continued the trend of declining MLT official export credits under the Arrangement that began in 2013, with a corollary surge in trade-related activity occurring outside Arrangement terms.[42]

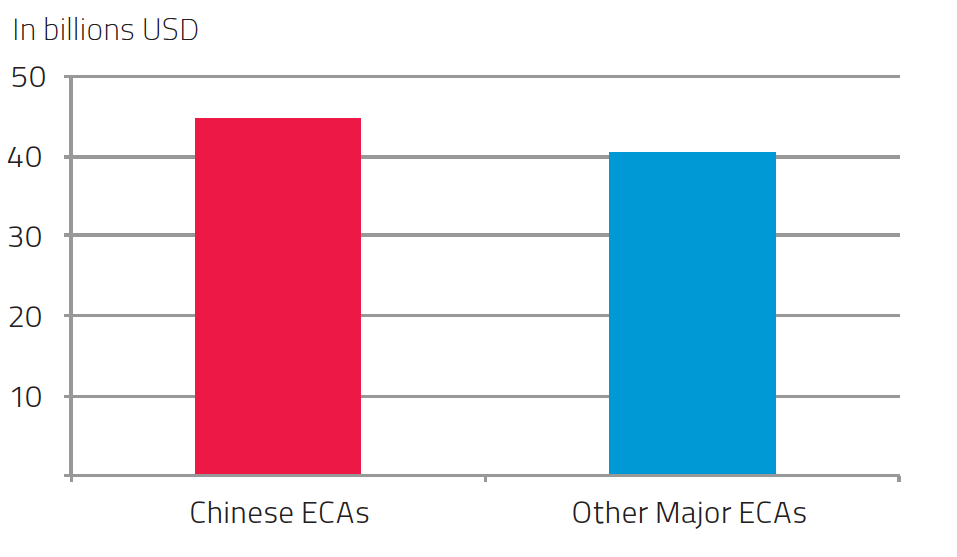

There has been a move towards providing untied investment financing by OECD Participants. Under this activity, an ECA provides support to a domestic company seeking to take an equity stake overseas. This investment is a form of untied support in that there may not be any international trade of goods or services. Technically, untied investment financing does not fall under the Arrangement and appears to be a reaction by some OECD Participants to promote national interest in the face of the increased activity by non-OECD Participants, such as China and India. In an untied financing programme, an ECA provides debt financing that facilitates international trade, but for which procurement from the ECA’s home country is not a prerequisite. As a result, untied financing can still lead to procurement or a host of other benefits, such as access to the natural resources resulting from an ECA-funded project. By taking an equity stake, domestic companies can potentially drive future procurement or play a role in the selection of an engineering, procurement, or construction contractor. Many programmes use strategic sourcing of raw materials or other national interests as their justification, versus the traditional export promotion model.

Figure 1 Comparison of Global Trade-Related Investment Support – Chinese ECA vis-à-vis Other Major ECAs in 2017[44]

There has also been a move towards creating export credit programmes operating under market-oriented principles, competing with commercial banks to support domestic exports rather than acting as a lender of last resort. These programmes are referred to as “market windows” and they also lie outside of the scope of the OECD Arrangement. In a market-window programme, an ECA offers pricing competitive with the commercial market; as such a market window does not necessarily result in lower financing costs compared with financing provided under the OECD Arrangement. However, ECAs have more flexibility on amortization structures, down payments, and fees or allow for local cost financing in excess of 30%, as the transaction is not covered by OECD rules. The UKEF does not operate a market window, while historically Canada’s export credit agency (EDC) and the German KfW/IPEX Bank – both OECD Participants – have offered such commercial approaches to official financing. Total EDC and KfW IPEX-Bank market window activity increased in 2013, with both market window players seeing increases in activity between 2012 and 2013. Japan and Korea are also now following such an approach.

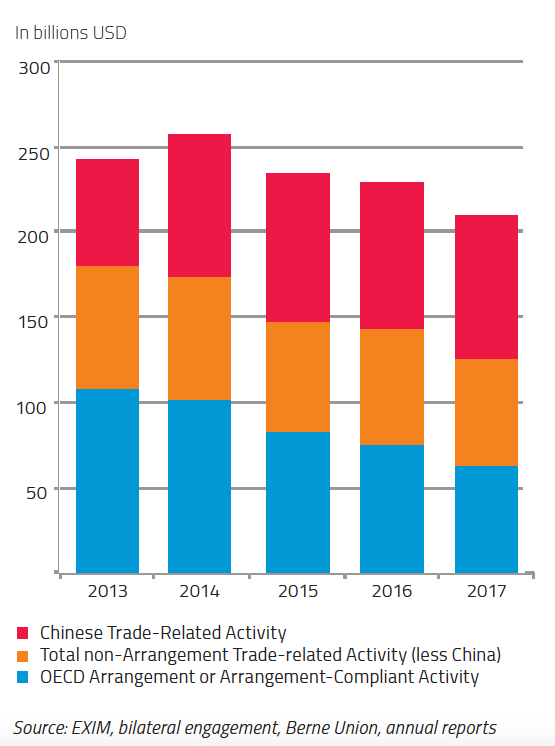

Figure 2 indicates the extent to which OECD Arrangement Participants have been shifting towards non-Arrangement activity since 2013. It highlights that between 2013 and 2017, activity covered by the OECD Arrangement dropped 6% to just under 55% of total activity, with a commensurate gain in non-arrangement covered export support. This shift has occurred at the same time as the total value of export support has decreased by approximately $60 billion.

Figure 2 Arrangement vs. Non-Arrangement Activity By Participants to the OECD Arrangement[45]

In addition to competing against these new non-OECD Arrangement export credit support programmes implemented by OECD Participants, UKEF is also facing the pressure from non-OECD Participants such as China, India and Brazil. For example, in China, the CEXIM Preferential Export Buyer’s Credit offers a 2% interest rate, 5-year grace period and a 10-20 year repayment period. It will finance 85% of the contract value and the denominated currency is US dollars. Alternatively, a Government Concessional Loan also offers a 2% interest rate, 5-year grace period and 10-20 year repayment period, but finances 100% of the contract value and is denominated in Renminbi (the official currency of China). CEXIM is able to offer these loans in combination with standard loans depending on what gives Chinese exporters the best chance to win an export contract in line with China’s foreign policy strategy. The features of these programmes can also be modified, such as extending the grace period, to further attract the borrower.

Figure 3 indicates the relative size of OECD Arrangement compliant activity; non-Arrangement compliant activity by both OECD Participants and non-Participants less China, and China’s trade-related export support activity. It suggests that in less than 5 years, OECD arrangement compliant activity has been displaced as the primary source of export support, by China and non-Arrangement activity.

Figure 3 Total Official Trade Related Support[46]

UKEF is thus faced with a strategic dilemma in the context of uneven global competition. The expansion of non-Arrangement activities increases the pressure on UKEF to create their own OECD Arrangement avoidance programmes. However, this further jeopardizes the level playing field and contributes to an export subsidy race. Figure 4 sets out the distinction between the three models of ECA operating and indicates that as yet, the UKEF operates only export credit activities that fall under the OECD Arrangement. It is among a minority of seven ECAs that have not expanded their Non-Arrangement activities. This expansion of non-Arrangement export credit support programmes has implications not only for the level playing field, but also for the regulatory framework governing export credit support and the compatibility of some of these new programmes with the obligations under the WTO SCM. The following section focuses on this issue of compliance.

Figure 4 Major ECA Countries by Programme Type[47]

Given the relatively declining scope and membership of the OECD Arrangement, the weight of regulating export credit activities is gravitating towards the multilateral WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM) with binding rules, enforced through a dispute settlement mechanism entrusted to respect the obligations of the Agreement. These rules, however, are not as detailed as the OECD Arrangement, for example, they do not address the environmental, social and human rights concerns of the OECD Common Approaches, and nor do they cover trade in services.

Article 3 SCM stipulates, in relevant part, that a Member shall neither grant nor maintain subsidies contingent, in law or in fact, whether solely or as one of several other conditions, upon export performance, including those illustrated in Annex I. Under the SCM, export subsidies are defined as those targeted to directly affect exports by assisting the domestic producer against its competitors in foreign markets. As they inherently favour domestic goods that are exported over competing foreign goods in export markets, there is no burden of proof as to its specificity or adverse effects. A prohibited subsidy must be withdrawn.[48]

The Annex I’s Illustrative List of export subsidies referred to under Article 3.1(a) SCM further clarifies what can be considered to be a prohibited “export subsidy.” The relevant provisions from Annex I are (j) and (k).[49] In the WTO Brazil- Export Financing Programme for Aircraft case, the Panel stated that: “The second paragraph of Item (k) provides that ‘an export credit practice’ which is in conformity with the “interest rate provisions” of the OECD Arrangement shall not be considered an export subsidy prohibited by the SCM Agreement.”[50] The Appellate Body’s Article 21.5 Implementation Report provided further clarity, stating that while Article 15 of the OECD Arrangement defines the minimum interest rates applicable to the officially-supported export credits as the CIRRs, it is not the only benchmark to assess the material advantage of an export subsidy. However, the Member has to provide evidence from comparable transactions in the marketplace.

On the other hand, any WTO member may use the ‘safe harbour’ exception allowed by the second paragraph of Item (k) – when applying the OECD standards. This includes the whole content of the Arrangement and its annexes, which is to be understood in its dynamic negotiation. For any new arrangement in the OECD and its Annexes replacing the 1979 undertaking is to be considered by the WTO.[51] However, this application of the Item (k) paragraph two ‘safe harbour’ is not unequivocal, most significantly in the area of ‘matching’ clauses. Under Article 18 of the OECD Arrangement, Participants are provided the possibility of matching the terms of an offer from an ECA operating both inside and outside the Arrangement.[52] This is seen as a form of ‘self-help’ for the Participants, and a deterrent against undercutting OECD Arrangement terms.[53]

In the Brazil-Export Financing Programme for Aircraft dispute, Canada argued that its contested subsidies were permitted because they fell within the safe harbour of paragraph 2 of Annex I Item (k) in the SCM Agreement. Further, that the OECD Arrangement permitted matching of concessional interest rates, either those offered by a competing country on the basis of provisions of the OECD Arrangement, or as was relevant here, in derogation from the Arrangement, through matching. The Panel, however, opined that while it recognized that matching of derogations is permitted under the OECD Arrangement, this did not alter the fact that both the original derogation and the matching remain, by the Arrangement’s own terms out of conformity with the provisions of the Arrangement.[54] Matching can only be permitted under the safe harbour if the matched export credit support did not derogate from the OECD Arrangement. The Panel further reasoned that if the OECD Arrangement was incorporated into the SCM Agreement such as to permit matching of derogations of Participants, non-participants in the OECD Arrangement would be at a disadvantage, as they would lack knowledge of such derogations and therefore the opportunity for matching them.[55]

The relevant findings of the Brazil – Export Financing Programme for Aircraft dispute indicate that the Item (k) paragraph 2, safe harbour, has been interpreted narrowly. It is available only for those forms of export credit support to which the interest rates provisions of the OECD Arrangement are applicable – that is, direct credits. It does not apply to export credit support in the form of pure cover (Item (j)), when it is provided to exporters on terms more favourable than the market rate. This is even if it conforms fully to the minimum premium and other disciplines in the OECD Arrangement. As such, matching is no defense to export subsidy claims in a WTO dispute. Some commentators argue that in theory, export credit support benefiting from the safe harbour remains vulnerable (i) to WTO challenge if it causes certain enumerated forms of economic harm to other WTO Members’ interests – so-called adverse effects; and (ii) to unilateral countervailing duty action if injury to another country’s domestic industry is shown.[56]

For a ‘matched offer’ permitted under the OECD Arrangement’s Article 18 derogation for its Participants to be assessed under the WTO SCM, a separate challenge would need to be brought by an injured party as a Member of the WTO. To bring a successful WTO challenge to suspected export credit subsidy programmes, the requesting party needs to make a prima facie case that: first, the other government provides export financing, second, that the financing is contingent on export performance, and third, that the rates at which the financing is provided are below market rates. Having made this case, the burden of demonstrating that the official export credits comply with the WTO SCM, or qualify for the safe harbour, procedurally shifts on to the responding party.

Yet disputes over export credit subsidies in the WTO remain rare. Although the US has been vocal in its criticism of China’s export support programmes, it has yet to bring a case to the WTO Dispute Settlement Mechanism (DSM) nor has it attempted to countervail an export credit subsidy. This may be partly because of the lack of transparency surrounding financial details of specific transactions. It may also be due to the time-consuming nature of the WTO dispute settlement procedure, increasingly unable to respond effectively to the fast pace of negotiated trade finance transactions.

Instead, the US and other countries with major ECAs have chosen diplomacy rather than litigation with China. In 2012, the US launched negotiations with China, through the Strategic and Economic Dialogue[57] to try to come to an agreement on guidelines to govern export credit financing. The International Working Group on Export Credits (IWG) was established: “To make concrete progress towards a set of international guidelines on the provision of Official Export Financing that, taking into account varying national interests and situations, are consistent with international best practices, with the goal of concluding an agreement by 2014”. The first plenary meeting of the IWG took place in 2012.[58] Many delegations in principle supported the view that the overall objective should be to eventually agree on a “successor undertaking” to the current OECD Arrangement, in sense of Item (k) of Annex I of the SCM. However, by 2019 no clear consensus over these issues had emerged from the IWG.[59] Meanwhile, it is becoming increasingly clear that the OECD Arrangement no longer regulates most of the export credit support programmes from most of the ECA countries, while enforcement under the WTO SCM does not address the official export credit support to trade in services nor the sustainability concerns of the OECD Common Approaches.

UKEF is operating in a highly aggressive yet increasingly unruly environment for official export credit support. In order to secure the export contracts necessary to absorb the maximum£50bn headroom, both industry and UKEF need to increase their competitiveness while abiding by the rules of the trading system, or risk contributing to the disruption of the level playing field. After Brexit, depending on the final agreement, the UK may transpose EU competition and State aid rules into UK domestic legislation. The Competition and Markets Authority would then have the UK-wide role of enforcing and supervising State aid. The UK will need to apply to be an individual Participant of the OECD Arrangement but will continue as an individual Member of the WTO.

Other non-economic legal frameworks are also applicable to the UKEF, including the OECD Common Approaches, the Equator Principles.[60] Alongside the compliance concerns surrounding official export credits and subsidy control, ensuring compliance with sustainability objectives may also not be an easy task in light of the search for more export opportunities in such an overcrowded arena. Several complaints have been raised,[61] including by Ban Ki Moon, that the UK’s export credit agency had provided billions of pounds in recent years to support businesses involved in oil and gas schemes around the world, which are difficult to reconcile with the UK’s commitments under the Paris Agreement.[62]

UKEF initiatives all currently fall under the scope of the OECD Arrangement and are compliant, such as increased risk appetite, the proposed changes to foreign content requirements and the new General Export Facility (GEF) which allows UKEF to support exporters’ overall working capital requirements, rather than linking support to specific export contracts. However, the expansion of non-Arrangement export credit support programmes, which raise WTO compliance questions, places strategic pressure on UKEF to devise similar initiatives to secure more export opportunities. One controversial proposal for changing the UK financing approach is the renewed call for the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID) to link some of its annual £13bn foreign aid budget with export credit.[63] Under its bailout programme, the IMF and World Bank subject indebted countries to strict limits on the amount they can borrow on a non-concessional basis. However, UK export finance is not concessional. UK companies are therefore locked out of those developing country projects that require concessional finance. As a development agency, DfID does not want to facilitate the poorer economies getting into debt through borrowing. UK exporters, however, point out that they are losing opportunities because this is not the case in most other ECA countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, Italy and France where their ECAs combine loans with a grant or aid element. However, such a strategy could be seen as a move away from the market failure rationale for official export credit support.

Indeed, the UK government generally, rather than UKEF specifically, could more usefully work directly with businesses to strengthen their competitiveness through providing skills training to match the needs of the international digital economy, start-up incentives and strengthen the ability of small businesses to identify and enter international supply chains. This would serve the UK’s long-term competitiveness, rather than contribute to unsustainable support through combining export credit financing with development aid.

In the event of Brexit, the UK Government will also have an important independent role to play in the call for a more level playing field in export credit support. This could be achieved through advocacy and proactive negotiations in the International Working Group (IWG) on Export Credits. International cooperation is required to supplement and clarify the rules to address these new market developments, as well as the blurred lines around aid and trade, and concessional finance and export credit. These are needed to maintain the benefits of transparency and competition. Pursuit of a level playing field could also be sought through a new wave of WTO litigation in the area of non-OECD Arrangement covered export credit support. There may, however, be reluctance to take such an approach. The world of official export credit support is fast moving, opaque and unashamedly mercantilist. The attraction of the OECD’s soft law approach was that while it may not have a strong enforcement arm to clarify interpretative ambiguities and bring rogue measures into conformity, it has provided the self-help deterrent of matching. In this way, the Participants were able to operate a relatively stable environment behind closed doors, through matching or the threat of matching overly generous offers from other Participants.

Yet while significant and increasing volumes of export credit support do not conform to the OECD approach, the strategy of litigating in the WTO has not been chosen. Perhaps such an approach is viewed as lifting the lid too far off this bastion of economic nationalism. There is a dilemma in pursing disputes in the WTO for those countries seeking to design new export credit support programmes that do not fall under the OECD Arrangement, because it is unclear whether they are compliant with the SCM. To litigate against another ECA may be opening a Pandora’s box, with the potential for retaliation. Moreover, the WTO is as yet unable to address the environmental, due-diligence, social and human rights issues that are involved in supporting overseas exports. In such a situation, the option of promoting the work of the IWG with a view to replacing the OECD Arrangement with a more universal and comprehensive instrument is both rational and desirable for the UK.

UKEF is recalibrating its finance packages to meet the changing needs of businesses seeking contracts overseas and entering international supply chains, through flexible foreign content requirements and taking on riskier contracts. Yet alongside implementing flexible and competitive terms and conditions for export support through the UKEF, the UK Government also needs to work closely with the private sector and through education and social policies to improve the international competitiveness of UK businesses; meeting the skills shortage and building their capacity to enter into new international supply chains. This is unlikely to be achieved through export credit support.

The other challenge lies externally. The most recent surge in aggressive competition in official export credit support has been accompanied by a weakening of the complex legal framework that operated to prevent a race to the bottom in terms and conditions of export financing. The OECD Arrangement no longer controls as much of the current export activity as before, nor the major ECA players of today. Previously, the linkages between the more detailed but soft law OECD Arrangement and the binding prohibitions for export subsidies under the WTO SCM operated dynamically to contain most export credit support, most of the time.

As the new major players are not Participants in the OECD Arrangement and Common Approaches, the WTO SCM agreement has become the main legal deterrent, despite its weakness in not covering trade in services or the sustainable development dimensions of official export credit support. Yet there has been a reluctance on the part of WTO Members to challenge official export credit support. This may be partly because the increasingly time-consuming WTO dispute settlement procedure is inadequate to respond to the fast pace of trade finance transactions. It could also be partly because of the overall opacity surrounding officially supported export credit programmes and the fear of retaliation. A dilemma may have emerged for Members seeking to prevent unfair competition in the provision of export credits, for fear that they also may well be operating non-compliant export support in order to secure overseas contracts for domestic industries. This could either be through matching, or through operating programmes that do not fall under the narrow interpretation of safe harbour under Item (k) Annex 1 to the SCM.

In this changing financial and regulatory environment, the UK Government is faced with the strategic choice of taking a strong pro-competition position domestically, as well as within international bodies such as the WTO, OECD and the IWG, or by fighting fire with fire and developing its own non-Arrangement type export credit programmes that may be in conflict with the SCM. This paper argues that the former option is preferable for economic efficiency considerations and long-term competitiveness, even though it may result in a reduced role for the UKEF. There is, therefore, a two-fold challenge for the UK Government. First, the UK Government needs to identify new ways to promote economic efficiency and competitiveness while avoiding corporate welfare. This is necessary to secure UK export markets for UKEF to support, whilst respecting international rules on subsidies and environmental, social, human rights and ethical standards. Second, the current economic slowdown in export growth along with the rise of unruly export credit support programmes and clearly calls for heightened cooperation among ECA governments. A chill on WTO enforcement of export credit support rules and the declining relevance of the OECD Arrangement could potentially spur on new forms of international cooperation, such as the negotiations in the IWG for export credits. For there is a long-term collective interest in preventing publicly-funded yet opaque subsidy wars in export credit terms and conditions, with known negative economic, political, social and environmental repercussions.

[1] UK Export Finance is the operating name of the UK’s Export Credits Guarantee Department.

[2] See: UKEF homepage https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/uk-export-finance/about.

[3] Liam Fox plans to increase UK export target after Brexit. Financial Times. August 21 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/116c588c-a487-11e8-8ecf-a7ae1beff35b

[4] This £50bn limit is an HMT exposure control.

[5] UKEF Annual Report 2018-2019. p24.

[6] Half the decrease was the result of a foreign exchange loss of £65 million for 2017-18. UKEF Annual Report 2017-2018. p16.

[7] Brexit Britain looks to Commonwealth 2.0. Euractiv.com: https://www.euractiv.com/section/uk-europe/news/brexit-britain-looks-to-commonwealth-2-0/

[8] In 2017 world trade growth stood at 4.6%, dropping to 3% in 2018 and is expected to drop further to 2.6% in 2019. See https://www.wto.org/english/news_e/spra_e/spra255_e.htm (accessed July 3 2019).

[9] Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition. EXIM Bank. June 2018. p30. https://www.exim.gov/sites/default/files/reports/competitiveness_reports/2018/EXIM-Competitiveness-Report_June2018.pdf (accessed July 3 2019).

[10] Hidehiro Konno, From Simple to Sophisticated. OECD (1998), The Export Credit Arrangement: Achievements and Challenges 1978/1998, OECD Publishing, Paris. p95.

[11] Corporate Welfare Wins Again in Trump’s Washington. New York Times Opinion. May 7 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/07/opinion/export-import-bank-trump-corporate-welfare.html

[12] Bagwell, Kyle, & Robert W. Staiger. 2002. The Economics of the World Trading System. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. 2006. Bagwell, Kyle, & Robert W. Staiger. Will International Rules on Subsidies Disrupt the World Trading System? 96 Am. Econ. Rev. 877–895.

[13] WTO Panel Report, Canada – Measures Affecting the Export of Civilian Aircraft – Recourse by Brazil to Article 21.5 of the DSU (Canada – Aircraft (Article 21.5 – Brazil)), WT/DS70/RW, adopted 4 August 2000. para 5.137.

[14] For a discussion on the desirability of subsidy control see: Alan O. Sykes. The Questionable Case for Subsidies Regulation: A Comparative Perspective. Fall 2010: Volume 2, Number 2. Journal of Legal Analysis.

[15] The Arrangement applies to all official support for exports of goods and/or services, or to financial leases, which have repayment terms of two years or more. This is regardless of whether the official support for export credits is given by means of direct credit/financing, refinancing, interest rate support, guarantee or insurance. Special sectoral Guidelines apply to ships, nuclear power plant, aircraft and project finance transactions. The Arrangement does not apply to military equipment and agriculture products.

[16] Johnson, Harry G. 1965. Optimal Trade Intervention in the Presence of Domestic Distortions. In Richard Caves, Harry Johnson, & Peter Kenen, eds., Trade, Growth and the Balance of Payments. New York: Rand McNally, Johnson (1965) cited in Sykes footnote 11.

[17] D. Coppens. How Much Credit for Export Credit Support under the SCM Agreement? Journal of International Economic Law 12(1), 63–113. 2009 p.66.

[18] Hufbauer, Gary Clyde, & Joanna Shelton Erb. 1984. Subsidies in International Trade. Washington: Institute for International Economics; Gary Clyde Hufbauer, Meera Fickling and Woan Foong Wong. Revitalizing the Export-Import Bank. Peterson Institute of International Economics. Policy Brief 11-6. May 2011

[19] This includes institutions such as the IMF, Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) and Development Finance Institutions (DFIs), the OECD Development Assistance Committee (DAC), the OECD, the Paris Club and the WTO.

[20] CIRRs should represent final commercial lending interest rates in the domestic market of the currency concerned and closely correspond to the rate for first-class domestic borrowers.

[21] R.R. Baxter. International Law in Her Infinite Varieties. 29 International & Comparative Law Quarterly. 549, 1980.

[22] Andrew T Guzman, Timothy L Meyer. International Soft Law. Journal of Legal Analysis. Spring, 2010: Volume 2, Number 1.

[23] Brazil is only Participant to OECD Arrangement in respect of Aircraft Transactions.

[24] Liam Fox plans to increase UK export target after Brexit. Financial Times. August 21, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/116c588c-a487-11e8-8ecf-a7ae1beff35b

[25] Industry data confirm this. For example, car exports decreased to both EU and non-EU countries in the three months to December 2018. See: Josh De Lyon and Swati Dhingra. UK economy since the Brexit vote: slower GDP growth, lower productivity, and a weaker pound. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/europpblog/2019/03/22/uk-economy-since-the-brexit-vote-slower-gdp-growth-lower-productivity-and-a-weaker-pound/

[26] UKEF Annual Report 2018-2019. p24. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/718043/ukef-annual-report-2017-to-2018.pdf

[27] Chinese MLT Tables are composed of CEXIM’s Buyer’s and Seller’s Credit programmes and Sinosure’s MLT activity. Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition. EXIM Bank. June 2018. p 19.

[28] The Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition. noted: “As of June 6, 2018, there are nearly $43 billion in transactions in Ex-Im’s pipeline that require a vote by Ex-Im’s Board of Directors that could support an estimated 250,000 U.S. jobs.” EXIM Bank, June 2018. p3.

[29] See: One More Item for the 2019 ‘To Do’ List: Reauthorize the Export-Import Bank. US Chamber of Commerce. https://www.uschamber.com/series/above-the-fold/one-more-item-the-2019-do-list-reauthorize-the-export-import-bank

[30] Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition. EXIM Bank. June 2018. p22.

[31] Foreign content consists of any portion of an export that originates outside the ECA’s, the exporter’s, and the foreign buyer’s countries.

[32] Government response to the Consultation on UKEF’s Foreign Content Policy: https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/public-consultation-on-foreign-content-policy

[33] Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition. EXIM Bank. 2017. p31.

[34] UK Export Finance. Foreign Content Policy Consultation Document April 3 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/public-consultation-on-foreign-content-policy

[35] Such a commitment would involve a statement by the applicant justifying the application of this Principle, which in UKEF’s determination justifies UKEF’s provision of support. UK Export Finance. Guidance on the UKEF’s Approach to Foreign Content https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/public-consultation-on-foreign-content-policy/outcome/guidance-on-ukefs-approach-to-foreign-content

[36] Such a commitment would involve a statement by the applicant justifying the application of this Principle, which in UKEF’s determination justifies UKEF’s provision of support. UK Export Finance. Foreign Content Policy Consultation Document April 3 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/public-consultation-on-foreign-content-policy/foreign-content-policy-consultation-document.

[37] Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition. EXIM Bank. 2018. p26.

[38] Ibid. p28

[39] Ibid. p19

[40] Ibid. p19

[41] Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition. EXIM Bank. 2017. p18

[42] Activity under the Arrangement was not down across the board. For example, UKEF increased its activity under the Arrangement (+198%), along with France (+24%), Italy (+93%), Sweden (+141%) growth in their MLT programmes. Although this growth was offset by falling volumes in the US (-97%), Japan (-63%), Germany (-39%), and Korea (-23%). Ibid. p18

[43] Japan Bank for International Cooperation. Annual Report. 2017.

[44] Reproduced from The Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition. EXIM Bank. 2018. p19.

[45] Reproduced from The Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition. EXIM Bank. 2018. p19

[46] Reproduced from The Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition. EXIM Bank. 2018. p20.

[47] Reproduced from The Report to the U.S. Congress on Global Export Credit Competition. EXIM Bank. 2017. p10.

[48] However, derogation from this provision has been provided to the countries falling under Annex VII list of the ASCM till they reach a GNI per capita of US$ 1000 for consecutive three years.

[49] Item (j) The provision by governments (or special institutions controlled by governments) of export credit guarantee or insurance programmes, of insurance or guarantee programmes against increases in the cost of exported products or of exchange risk programmes, at premium rates which are inadequate to cover the long‑term operating costs and losses of the programmes. Item (k) The grant by governments (or special institutions controlled by and/or acting under the authority of governments) of export credits at rates below those which they actually have to pay for the funds so employed (or would have to pay if they borrowed on international capital markets in order to obtain funds of the same maturity and other credit terms and denominated in the same currency as the export credit), or the payment by them of all or part of the costs incurred by exporters or financial institutions in obtaining credits, in so far as they are used to secure a material advantage in the field of export credit terms. Provided, however, that if a Member is a party to an international undertaking on official export credits to which at least twelve original Members to this Agreement are parties as of 1 January 1979 (or a successor undertaking which has been adopted by those original Members), or if in practice a Member applies the interest rates provisions of the relevant undertaking, an export credit practice which is in conformity with those provisions shall not be considered an export subsidy prohibited by this Agreement.

[50] Panel Report ((14 April 1999)). Brazil – Export Financing Programme for Aircraft. WT/DS46/R. WT/DS46/R. ¶¶1.1-1.10.

[51] Brazil – Export financing programme for aircraft: Recourse by Canada to Article 21.5 of the DSU; Report of the Appellate Body (WT/DS46/AB/RW) and Report of the Panel (WT/DS46/RW)

[52] Article 18. Matching. Taking into account a Participant’s international obligations and consistent with the purpose of the Arrangement, a Participant may match, according to the procedures set out in Article 45, financial terms and conditions offered by a Participant or a non-Participant. Financial terms and conditions provided in accordance with this Article are considered to be in conformity with the provisions of Chapters I, II and, when applicable, Annexes I, II, III, IV, V, VI and VII.

[53] See D. Coppens. How Much Credit for Export Credit Support under the SCM Agreement? Journal of International Economic Law 12(1), 63–113. 2009.

[54] Panel Report, Canada – Aircraft (Article 21.5 – Brazil), para 5.125; Panel Report, Canada – Aircraft Credits and Guarantees, ¶7.169.

[55] Panel Report, Canada – Aircraft Credits and Guarantees. ¶7.177.

[56] Dominic Coppens and Todd Friedbacher. A tale of two rules: The intersection between WTO and OECD disciplines on export credit support. The Future of Foreign Trade Support – Setting Global Standards for Export Credit and Political Risk Insurance.’ 2015. https://www.globalpolicyjournal.com/blog/26/11/2014/tale-two-rules-intersection-between-wto-and-oecd-disciplines-export-credit-support

[57] https://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/hp1037.aspx

[58] Altogether 15 major export credit providers attended the plenary, including the OECD Participants as well as China, Brazil, the Russian Federation, Turkey, Malaysia and Israel.

[59] The EU, for example, favours a horizontal approach that look first at general provisions on maximum repayment terms, down payments, interest rates, premia etc. applicable to all export credit transactions irrespective of the industrial sector concerned. China on the other hand, prefers the option of starting the process by looking at sectors, such as medical equipment and shipping. See: A Brief Background Note on the ongoing negotiations of the International Working Group (‘IWG’) on Export Credit. CAPEXIL. http://capexil.org/background-note-iwg-on-export-credit/

[60] https://equator-principles.com/

[61] The UKEF has been the subject of criticism by UK-based NGOs; The Corner House has claimed that the ECGD has in effect provided public subsidy for bribery; Campaign Against Arms Trade has argued that the UKEF provides excessive levels of support for arms sales; Jubilee Debt Campaign has argued that the cancellation of debts owed to the ECGD should not be counted towards UK Official Development Assistance Tables; World Wide Fund for Nature argues that excessive greenhouse gases are emitted from UKEF-supported projects and that this is inconsistent with wider UK environmental policy.

[62] Ban Ki-moon tells Britain: stop investing in fossil fuels overseas. The Guardian Newspaper. February 24 2019. See: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/feb/24/ban-ki-moon-britain-stop-invest-fossil-fuels-overseas

[63] Rundell, S, Levelling the playing field: UK exporters want more. Global Trade Review. 13/03/2019. https://www.gtreview.com/supplements/gtr-uk-2019/levelling-playing-field-uk-exporters-want/).