8 November, 2024 – David Henig is the Director of the UK Trade Policy Project at the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE).

8 November, 2024 – David Henig is the Director of the UK Trade Policy Project at the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE).

Just for a short time, all went quiet in the UK trade world. A Labour government meant the end of Conservative traumas over EU relations regularly resurfacing. President Biden didn’t do trade deals with anyone, and new UK Ministers made few swift decisions. Meanwhile, the EU reset has been more about smiles than substance.

To be fair, that wasn’t going to last. Though the secrecy instincts of Whitehall linger with a new government, there isn’t much point in a trade strategy shaped without extensive external input and some controversy over decisions. This will need to happen at some point (whether before or after publication) and is an inevitable consequence of choosing priorities.

Similarly, judging by ministerial visits, the only trade deal close to conclusion is with the Gulf Cooperation Council, which if agreed is likely to prove controversial, perhaps in terms of labour and environmental provisions, as well as making only a limited contribution to growth. Meanwhile, arguments over the level of ambition shown in the UK-EU reset are intensifying, as UK stakeholders advocating for ambition increasingly hear frustration from their contacts in Brussels.

President Trump’s re-election changes everything. Trade is a significant part of his agenda, specifically raising tariffs – which we know to be economically damaging. Suddenly commentators are talking about trade again, specialists are being invited to offer their views, and ministers are expected to give answers. Some raise the spectre of a 1930s-style trade meltdown or, more realistically in an age of international supply chains, of interlinked trade wars.

Around two-thirds of UK trade takes place with the US or EU, and these relationships are up for grabs. They are also interrelated in what we could call a new ‘great game’ between those two and the other major powers of world trade: China certainly, and India arguably. This is the geopolitics which the middle powers including the UK, Canada, Japan, and Mexico will need to navigate.

Starting with the basics of Trump’s plans, what is most discussed is a tariff on all goods imports, of 10-20%, with those from China charged higher at around 60%. There is no clarity as to whether this comes on top of MFN levels or not, and that probably doesn’t matter. This seems highly unlikely to be implemented.

Given that a large proportion of imports will be intermediate goods, and others, final consumer goods with no immediately available domestic substitutes, such a policy would be immediately economically damaging to the US. Large companies based in the US will already be making their cases for exemptions, and what we are more likely to see will be targeted or used as bargaining leverage.

More likely is the US starting a series of individual trade conflicts which need to be considered separately, but which could add up to potentially considerable economic damage. Given the integrated nature of global supply chains, it is hard to quantify that with any accuracy, but it will require constant UK government attention to manage.

The UK is likely to be affected in at least three ways: it is a flagrant breach of WTO rules, about which we generally care quite deeply. It may also lead to a global trade war. Finally, the US is our largest single trade partner.

Taking the last first, on UK figures only 30% of our exports to the US are goods. Yet that is still £59 billion, a little under 15% of our goods total. Our sales of whisky, Rolls Royce engines or medicines may well be at risk. No government can ignore this, and doubtless officials have prepared plans for retaliatory measures if necessary. Of course, there will also be talks of a deal, either a full trade agreement or something more partial. Trump is more of a deal-maker than Biden, but anything substantive would probably once again become stuck on agricultural standards on which UK and US approaches seem irreconcilable.

On the second, the UK has so far stood aside from trade conflicts with China. This may become increasingly difficult as the threatened Trump tariffs may be used as leverage for the UK to align more with the US against China. Equally Trump’s tariffs may also lead to EU-US conflict, with the UK as residual damage, or many other permutations. This won’t be a good time for investor certainty.

For world trade rules it is hard to be positive, and maintaining broad agreement outside of the US would seem to be the best case. This will not be a conducive environment for WTO reforms and new plurilaterals, such as on e-commerce. Survival will be the name of the game.

The UK response should be different this time. Unequivocally the UK government will ideally declare a continued commitment to fair global trade rules. Under Trump’s first Presidency there were suspicions that this would be abandoned if the US offered any kind of bilateral deal, which increased suspicion globally without any evident upside. It should also work hard with other like-minded middle powers to counterbalance Trump-induced turbulence.

Various commentators have suggested that the UK government acts as an honest broker between the US and EU, or perhaps trade one off against the other. These should be rejected as not credible. We are novices in the world of trade negotiations, and this will be a battle of heavyweights in which our goal should be not to be crushed by either. It is far better to try to stay out of the fray as much as possible.

Others have seen the election of President Trump as the perfect opportunity for the UK to get closer to the EU, and for the government to put energy into a reset that already shows signs of losing momentum. For some supporters, there will also be the fear of the US pressuring the UK to choose which rules we follow.

What should be the principle here is to follow the money, or rather the main trade flows. With around half our trade, the EU relationship is far more important than that with the US. That’s even been recognised by Robert Lighthizer – USTR under the first Trump term and still close to the President.

Such a commitment isn’t absolute, where the UK can be a rule setter as in financial services, we should do so. For goods, if we have to be followers, the EU is the better model. This makes more economic sense, similarly on climate change measures where we have broad political agreement. There’s no doubt that it is in the UK’s economic interests to seek smoother trade with the EU, but ideally, that shouldn’t come at the expense of wider trade to which we remain committed.

Trade policy is back, it hardly went away in truth. However, in starting with a realistic view of the world, this UK government is better prepared. That needs now to extend to thinking through the limits of what’s possible, in bilateral and multilateral terms. In some ways, it will be every country for themselves. In others, there will be a lot of coordination and discussion. Setting out a clear path in public – one that includes respect for global rules, open trade, and follows our main economic interests – would be a very good start in responding to the new times.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher November 8th, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

25 October 2024 – Erika Szyszczak is a Professor Emerita and a Fellow of the UKTPO. Will Disney is a sustainability researcher and independent consultant.

25 October 2024 – Erika Szyszczak is a Professor Emerita and a Fellow of the UKTPO. Will Disney is a sustainability researcher and independent consultant.

The European Union is using trade measures to achieve a host of policies – climate change, human rights, labour standards – but for one policy area the EU has been hit by a global backlash. Voices within and outside of the EU are calling for a delay, and a re-appraisal, of its ground-breaking anti-deforestation Regulation which came into force on 29 June 2023. The EU has been forced to consider delaying the implementation of the Regulation by 12 months (until 30 December 2025) for large operators and traders. It has also been delayed for micro and small enterprises: until 30 June 2026.

The Regulation aims to promote ‘deforestation-free’ products and reduce the EU’s impact on global deforestation and forest degradation, as part of the action plan embracing the European Green Deal, the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and the Farm to Fork Strategy. Firms trading in the EU have been preparing for the full implementation of the Regulation by exercising due diligence in their value chains. This has been done to ensure that any trading in cattle, cocoa, coffee, oil palm, rubber, soya and wood, as well as products derived from these commodities, does not result from any deforestation, forest degradation or breaches of local environmental and social laws that occurred from 31 December 2020. However, tracing supply chains in a global economy is difficult, and the Regulation is complex. The European Commission only published guidance on the Regulation on 2 October 2024. This guidance does not provide a steer on which non-EU countries may be seen as high risk, indicating where greater due diligence should be exercised. It only presented the methodology that will be used to benchmark countries and regions in terms of their deforestation risk. Thus, the Regulation will introduce new and onerous customs checks, creating new technical barriers to trade.

The responsibility to ensure compliance with the Regulation lies with the firm placing relevant products on the EU market or exporting such products from this market. Failure to comply will result in penalties: potential fines of up to 4% of the firm’s EU turnover, and confiscation or exclusion from public funding or contracts. Penalties for non-compliance will be set under national law. However, it is anticipated that breaches of the EUDR will lead to criminal penalties.

The Regulation has not garnered total support even within the EU. Requests to postpone the operation of the Regulation emerged from the United States, fearing shortages of sanitary products. The WTO Director General, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, called for a delay and reappraisal of the law, especially in light of developing countries seeing the Regulation as lacking an understanding of land use and the costs and expertise needed to map land use.

As such, the Regulation is viewed by some as being discriminatory and punitive towards the global south. Certainly, the Regulation creates new technical barriers to trade, with criticisms that its compliance requirements are “overburdensome and ill-defined.”

Musdalifah Machmud, the former Indonesian Deputy Minister at the Coordinating Ministry for the Economy (now Expert Staff for Connectivity, Service Development, and Natural Resources), sees the Regulation as taking a derogatory attitude towards attempts in the global south to counter de-forestation, and makes this appeal:

“… Indonesia’s efforts on deforestation, its environmental reforms and its certification systems must be recognised within the EUDR and by European stakeholders more broadly.

Indonesia’s deforestation rates are now at their lowest on record, and 90 per cent below their peak a decade ago. The tired narrative of Indonesia – and its commodity producers – as environmental vandals must be dispensed with.”

When the EU adopted the Regulation, it was motivated by environmental concerns. Yet, could it be seen as another example of geoeconomics where the EU is protecting its political and economic interests? Is the EU forging a new framework to control supply chains and define its responses to global threats in international trade? Is this another example of the EU extending its extra-territorial reach into the economies of third states?

Despite resistance from both the public and private spheres, there are also loud voices supporting the Regulation. A coalition of cocoa companies including Nestlé, Ferrero, Mondelēz, Mars, Tony’s Chocolonely and NGOs such as the Rainforest Alliance and Solidaridad, “strongly oppose” calls to reopen the substance of the EUDR.

Stakeholders argue that any renegotiation or further delays will hinder the ability of firms and suppliers to shape business activities to address and report on this complex issue.

Data from the World Benchmarking Alliance’s (WBA) Nature benchmark, an NGO that measures companies’ impact on nature and biodiversity topics, highlights only 7% of the companies currently publicly disclose where their suppliers are based. Beyond resistance from companies to report on this issue, this low figure can also be attributed to the lack of a globally recognised framework to disclose on the topic.

The EU has been criticised for its lack of support for affected stakeholders, particularly regarding the delay in the lack of clarification and guidance on the exact systems which should be implemented to satisfy the Regulation.

The EU must create roadmaps and provide more clarity around the expectations of firms headquartered in the EU, as well as explain the support they should provide to suppliers during the transition. For example, helping suppliers by covering the costs of obtaining certifications for globally recognised sustainability standards.

The consequences of not implementing the policy could be substantial. Analysis from the NGO Global Witness suggests that even a 12-month delay could lead to 150,385 hectares of deforestation linked to EU trade, an area more than fourteen times the size of Paris. Therefore, EU regulators must act urgently if the EU is to avert CO2 emissions related to its market and trade and, ultimately, meet the bloc’s climate goals through the EU Green Deal.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher October 25th, 2024

Posted In: UK- EU

04 October 2024 – Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School.

04 October 2024 – Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School.

The 2024 World Trade Organization (WTO) Public Forum was sure to be a fascinating occasion given the interest in the topic, inclusivity and green trade, and the stellar cast of speakers. But what of the future of the WTO itself? Many observers have come to feel that with the negotiating function and the Appellate Body (AB) both log-jammed, there wasn’t much for the WTO to do apart from hosting events like the Public Forum.

Despite the logjam in negotiations and the apparent death (certainly more than a very deep sleep) of the Appellate Body, the WTO is still delivering value to its members in its routine committee work. It continues to promote transparency etc, and Dispute Settlement Panels still operate, though more like the way they did in the GATT era. Among DS nerds there was sympathy for the idea put forward by Sunayana Sasmal and me[1] that concerns over judicial overreach could be assuaged if the AB (if there were one) could decline to rule if the law was genuinely unclear. But as several Indian experts told us, if there is no AB, it’s not an issue.

Meanwhile, I only found one panel focussing on how to restore negotiations: our very own CITP panel on “Responsible Consensus”, i.e. persuading countries not to use their power to block decisions. It didn’t generate a lot of optimism. India, as well as the US, attracted quite a lot of criticism for its vigorous use of its legal right to veto moves that could affect its interests – even where there was a big majority of supporters. India’s position was elegantly and forcefully explained and defended by Prof Abhijt Das, an old friend of Sussex. He argued that even where other states might want to agree amongst themselves, India had a right to object to Plurilateral deals which might affect them adversely even when no actual obligations were created for them. But, interestingly, despite the delight of seeing many old friends from Delhi, there was little open official Indian engagement. It was striking that the Indian Foreign Minister chose last week to visit Geneva, to consult with UN agencies, but he didn’t visit the WTO. And there was no visible official US profile. On the other hand, China’s CGTN was listed as a Forum sponsor and hosted a lecture by Jason Furman, former senior adviser to Barack Obama. On CGTN, the Chinese DDG Zhang Xiangchen stated how the public Forum, “is a platform for all to make their voices heard” and he “encourages more communication among stakeholders and calls on the active participation of developing countries for a balanced outcome.”

This echoed the message that WTO DG Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala pushed in the sessions she spoke at. It was spelled out in the first ever WTO Secretariat Strategy document.

The WTO Secretariat as a body is seeking to do more than just service the wishes of the Member States. It is seeking to act as a facilitator, convenor and broker, in the absence of, and perhaps to recreate, the missing consensus. Inclusivity and sustainability were being pushed in sessions organised by the Secretariat. The message was that we cannot assume globalisation will benefit everyone without action being taken. This was the underlying theme: the Forum offered Public Diplomacy on behalf of the organisation. Was it just bland PR? One senior legal official told Sunayana and me that the WTO did seem to have found a way to create a new role and a new narrative for itself. The WTO had been very closely involved in the efforts to keep vaccine supply chains and some border crossings open during Covid, at the request of concerned parties and had brokered important agreements. It was “more important than ever”. The Secretariat is beginning to be more proactive and encouraging global dialogue.

Following these conversations, many of the observers we spoke to were somewhat sceptical, but not all. One of the UK’s leading trade specialists thought that this message of pro-active broader engagement was real and had been effective during the COVID period. Dr Ngozi has called for action on carbon pricing in an FT interview. If it could work, seeking to mobilise soft power rather than being the home of rulemaking and rule enforcement would be an excellent strategy. But there are pitfalls. Would it be too controversial in the face of division among members? Is there a risk that the Secretariat could be seen as overreaching its legitimacy in the same way as the Appellate Body? Can the WTO really survive without its key rulemaking and enforcing role? And what if Trump wins?

[1] https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/files/2024/02/Holmes_Sasmal_Not-Liquet-UKTPO-WP.pdf

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher October 4th, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

Tags: WTO

27 September 2024 – Ana Peres is a Lecturer in Law at the University of Sussex and a member of the UKTPO.

27 September 2024 – Ana Peres is a Lecturer in Law at the University of Sussex and a member of the UKTPO.

Lawyers, economists and political scientists are increasingly using a new term to frame discussions on current trade relations and policies: geoeconomics. This means that countries are intervening in strategic economic sectors not primarily for profit but to ensure autonomy, build resilient supply chains and secure access to valuable capabilities. Such approach contrasts with the ideals of free trade, market access and interdependence that shaped international trade for decades. These traditional ideals, even when supported by a so-called ‘rules-based system’, always posed challenges for developing countries to meet their objectives. So, what does geoeconomics mean for developing countries? Unfortunately, it threatens to sideline them even more.

Consider one of the main areas where geoeconomic strategies are at play: the development of clean technologies. Governments are implementing industrial policies to secure access to critical raw materials, an input for electric batteries, and to protect domestic production of electric vehicles (EVs). Such policies often require substantial subsidies. Recent discussions at the WTO Public Forum highlighted that a clear distinction between “bad” and “good” subsidies is not only desirable but essential to deal with many of the new and standing issues in the organisation. Beyond the question of their legality, we need to consider which countries have the financial resources to engage in this new wave of industrial policies – and what happens to those that do not. For instance, the UK’s former Conservative Secretary of State for Business and Trade, Kemi Badenoch MP, stated that the UK government would provide “targeted support (…) looking at what we can afford (…)”. If the UK, as a G7 economy, is concerned about affordability, developing countries face even greater challenges in this context.

An analysis of the proposed “Clean Energy Marshall Plan” suggests that a Harris administration in the US could use industrial policies to make developing countries dependent on US exports of clean technologies. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) to Latin America is shifting to “new infrastructure” sectors, such as energy transition. The EU signed a memorandum of understanding with Chile to promote sustainable raw materials value chains. All these developments reflect the geoeconomic trend, by prioritizing autonomy, resilience and access for wealthy countries, at the expense of those objectives for poorer countries.

Resource-rich developing countries are not defenceless in this geoeconomic world. For instance, Chile is one of the world’s largest suppliers of lithium (around 80% of all EU imports). The Chilean government’s response, creating the National Lithium Strategy to strengthen control over its reserves and maximise their benefits, offers a glimpse of one path resource-rich developing countries may follow. Similarly, Southeast Asian countries like Indonesia and Malaysia are trying to capitalise on the EV industrial policies of the US and China.

These examples show the power dynamics underlying international trade flows. While geoeconomics brings power and politics to the fore of current trade relations, it does not introduce them to the existing trade order. The process leading to the creation of the WTO and the surge of free trade agreements during the 1980s and 1990s reaffirmed the rule of law as central to promoting trade liberalisation. A rules-based framework should favour the stability and predictability of the global trading system, enabling countries to negotiate new topics and settle trade disputes. However, even in this ‘traditional’ WTO-led approach, law and power are closely linked. Restricting the role of power in trade agreements and institutions does not eliminate it from trade rules and negotiations. Developing countries have long struggled to have their voices heard in trade rulemaking and negotiations. For them, it has always been political.

The novelty of the geoeconomic framework is the recognition that economic and geopolitical powers are intertwined in policymaking. Governments are implementing policies beyond trade, covering areas like environmental protection, defence, health, and digital technologies. Geoeconomics shows how states use their economic and political power to achieve domestic goals and assert or maintain global leadership.

While geoeconomics is useful for describing the current context, it has not yet adequately addressed the position of developing countries. Like many frameworks applied to international trade, geoeconomics explains trade relations and trends from the perspective of the main players. In this case, the US, China and, to a lesser extent, the EU. Tensions between the US and China are driving a new division between allies and adversaries. This raises important questions: who decides which countries are friends or foes? Can – or should – developing countries take sides? What are the potential consequences? Could developing countries leverage the conflict between the world’s two largest economies to strengthen their positions? What will happen to developing countries that are not resource-rich? These will become defining questions for developing countries in the era of geoeconomics.

During the Cold War, the polarisation of global powers led third world nations to advocate for a New International Economic Order. They understood that their interests were sidelined in the global debate driven by ideological and political conflicts between the two superpowers. At the WTO Public Forum, the possibility of “third nations” or “middle powers” guiding multilateral trade efforts was raised, as an alternative to overcome the stalemate created by the clash between the US and China. However, such a heterogeneous group will have to find common ground if they move forward without the two biggest world economies. That is no easy task. This is why including developing countries in discussions about the geoeconomics of trade is so important today – to ensure their concerns are not overlooked or marginalised as they once again risk being caught in the middle of power struggles that threaten to leave them powerless.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher September 27th, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

Tags: Geoeconomics, WTO

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

23 September 2024 – Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School.

23 September 2024 – Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School.

In recent weeks Sir Keir Starmer has visited Germany, France, Ireland and Italy, each in the name, he says, of turning a corner on Brexit, resetting the UK’s relationship with Europe and – most importantly – raising economic growth. The OBR estimates Brexit in its current form to be costing the UK a permanent non recoverable 4% of GDP pa.

So far, the PM’s visits to the EU have been good symbolism. Recent UK opinion polling shows increased public support for building back closer ties with the EU, reflecting that there are many in the UK, including a growing contingent of “Bregretters”, who would like to repair the economic and political damage done since 2016. On the European side the optics of welcome have been decently warm, although perhaps this is not so very surprising after almost ten years of dealing with EU-shy Conservative governments.

However, it is quite striking that, at the time of writing, Starmer has not yet made a visit to Brussels. He may be waiting for Ursula von der Leyen to launch her second term Commission. However, his absence to date has been noted at the Berlaymont and his immediate rebuff of an EU proposal for a youth mobility scheme went down badly. EU officials are reported to be asking how serious about a Brexit reset he really is. There is doubt he has a clear strategy beyond his “red lines”[1].

While the new Commission awaits final confirmation, the UK has a breathing space which it can use to clarify its own strategy. But by the time the new Commission starts to plan its five-year agenda, in early 2025, the UK needs to have put together a clear proposal for the EU to react to. To be good enough to deliver an economic upturn for Britain, it will have to be more than just a few cherry-picked ideas and restatement of what the UK doesn’t want.

But even as he enthused about a bilateral deal with Germany on his Berlin trip, Starmer doubled down on his red lines of “no single market”, “no customs union” and “no rejoining the EU within his lifetime”. If he intends to stick to these red lines, he may find they hinder his goal to boost the UK economy, a point also made by the Resolution Foundation.[2]

EU officials have always insisted that the first requirement for improved relations with the UK would be a renewal of trust, and a willingness by the UK to adhere to the commitments it made in Boris Johnson’s 2020 hurried and flawed “get Brexit done” deal – the treaty formally known as the Trade & Co-operation Agreement (TCA).

The TCA is due for its first 5 yearly review in 2026. Although the EU has repeatedly made clear that they do not want to review the body of this agreement, the treaty does contain provisions for modifying some of its rules without modifying the treaty itself or making a new one. For example, the TCA Title X provides for “Regulatory Co-operation” which would allow UK and EU regulators to discuss and agree potential areas of joint interest, with a fairly open-ended agenda, and it includes concrete provisions for cars, aviation and medicines in annexes. They could then extend the models in other areas. Similarly, the UK-EU Joint Partnership Council which oversees the treaty can agree to change the rules of origin, and has already done so for electric vehicles.

Ahead of the 2026 review the EU has made it clear that the original Barnier red line of “no cherry-picking” no longer apply. Side agreements or “mini-deals” can be signed at any time. Their youth mobility proposal[3], for now declined, was a mini-deal and they have also proposed an SPS [4] mini-deal which would allow meat, fruit and vegetables and flowers to move between the UK and the EU more quickly. To get recognition of our food safety rules we need to make binding commitments to total equivalence, (including how we check third country imports). The British ambition of a comprehensive agreement on Mutual Recognition on Conformity Assessment is unrealistic. Piece by piece might work, including rejoining EU regulatory agencies as associates, eg EFSA and EASA.[5] There is scope for the signature of new UK-EU mini-deals on a range of topics including carbon pricing, aerospace and mutual recognition of professional qualifications. These could require formal endorsement by the Council of Ministers and even possibly the European Parliament, but they are a key avenue to explore. The UK government is placing its hopes in a deal on defence and security, which, although contrary to the Conservatives’ views, Labour hopes will have the broadest economic security dimension.

The UK also has the option to voluntarily match certain EU rules, to ease the burden of compliance on UK businesses. Known as “voluntary dynamic alignment”, it could be a useful approach in principle. It could also help reduce paperwork and the number of border checks faced by UK goods going into the EU. However, this would not eliminate paperwork and checks entirely – in order to do so, we would need to rejoin the EU or at least something like the EEA. On CBAMs, UK firms are unlikely to face any charges if the UK voluntarily aligns fully with the EU. However, unless we agree to be legally bound to apply ETS rules and carbon prices virtually to the EU’s (including coverage and how we have treated third country good that may enter value chains), UK firms will be subject to the need to prove compliance. It may be that the UK way of treating electricity in the ETS might be better than the EU’s plan but this is unlikely to be worth facing the CBAM process.

Often performative divergence such as the UKCA or UK REACH regimes, in the name of “sovereignty” deliver nothing to business except regulatory duplication. The gains to admitting the need to follow the “Brussels Effect” will be at least as much domestic, simplifying business and generating certainty that is needed to restore investment. However, the EU will not automatically recognise the validity of our rule enforcement, even though we have no choice but to accept EU quality certification. An EU negotiator said to me: “We’ll be like India”, i.e. tough on the UK. And they will get to pick more cherries than the UK.

As David Henig[6] points out, there is still appetite on the EU side for a better relationship. Yet, for the UK to benefit, it will need to be prepared to negotiate in all of the above areas. As part of quickly pulling together a new strategic plan, the UK must figure out what it can offer that the EU wants. At the same time, the UK must decide on its own top aims; identify where it can make offers that cost little but will show goodwill; and consider what it is prepared to give up, even though there may be some gain from regulatory autonomy in that sphere. It will not be all or nothing, but there has to be a package.

Unfortunately, the improvements to Brexit that would make the biggest and quickest difference for the UK’s economy are the ones that are currently off-limits, behind Starmer’s red lines. This does not mean the UK can’t do anything at all. There is some low-hanging fruit, including some sort of youth mobility deal. But to make a big difference in reducing border frictions and the uncertainty created by Brexit, the UK will have to go further than Starmer is willing to admit. Making this policy flex work is going to require engaging with the public openly. He could even try one of his now-familiar messages, along the lines of “the Brexit situation was a lot worse than we thought”.

The new EU Commission will start in January 2025. By that time, it would make sense to have dispel any doubts about the UK’s commitment to improved relations, and to be ready – after considering what the UK can offer the EU – to put some attractive proposals on the table. If we take the lead and find areas of mutual interest that generate visible benefits quickly, we can create the political momentum to go further.

[1] Poltiico https://www.politico.eu/article/keir-starmer-european-union-brexit-relationship-reset/?

[2] https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2024/09/Growth-Mindset.pdf

[3] See https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/sep/20/eu-youth-mobility-proposal-uk

[4] Sanitary and Phyto Sanitary ie Food safety.

[5] European Aerospace Safety Agency, European Food Safety Authority.

[6] https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/ECI_24_PolicyBrief_17-2024_LY04.pdf

Peter Holmes would like to thank Karen Triggs for her support in creating this blog post.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher September 23rd, 2024

Posted In: UK- EU

23 July 2024

23 July 2024

Minako Morita-Jaeger is Policy Research Fellow at the UK Trade Policy Observatory, a researcher within the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and Senior Research Fellow in International Trade in the Department of Economics, University of Sussex. She currently focuses on analysing UK trade policy and its economic and social impacts.

The UK is a services economy which accounts for 81% of output (Gross Value Added) and 83% of employment.UK services exports (£470 billion in 2023) are the world’s second largest after the US and 75% of its services exports are digitally delivered. The UK is ranked as world-leading in terms of data governance. Under the new Labour government, it is time to take the initiative on data flow governance at the global stage to achieve a sustainable and accountable digital environment. With the set back in the US negotiations on free data flows at the WTO, the UK can take the initiative to collaborate with the EU and Japan.

The EU-Japan EPA, which entered into force in 2019, lacked provisions on free data flows and personal data protection. This has now been addressed with the signing of the new protocol on 31 January this year which is incorporated into the EU-Japan EPA. The new EU-Japan protocol can be seen as game changers. First, they strike a balance between free data flows and legitimate public policy objectives. Under Article 8.81, measures that prohibit or restrict cross-border data flows, such as localisation requirements of computing facilities or network elements, are restricted. These provisions are similar to the existing digital trade provisions under FTAs/digital trade agreements led by the Asia-Pacific countries, such as the CPTPP.

Yet a significant difference with the Asia-Pacific style FTAs is the scope and definition of “legitimate public policy objective” (Art. 8.81.3 and its footnotes). The new protocol reflects the EU’s approach under the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) which provides more detail compared to the Asia-Pacific led digital trade agreements.

Another striking difference is that personal data protection is set as a fundamental right. The provisions regarding cross-border data transfers go together with the new provisions regarding protection of personal data (Art. 8.82). The clause is comprehensive and could be seen as the highest standard among existing digital trade agreements, including the EU-UK TCA. It underlines the importance of maintaining high standards of personal data protection to ensure trust in the digital economy and to develop digital trade. Such deep commitments between the EU and Japan were enabled by ongoing policy dialogues, including the EU-Japan Digital Partnership Council.

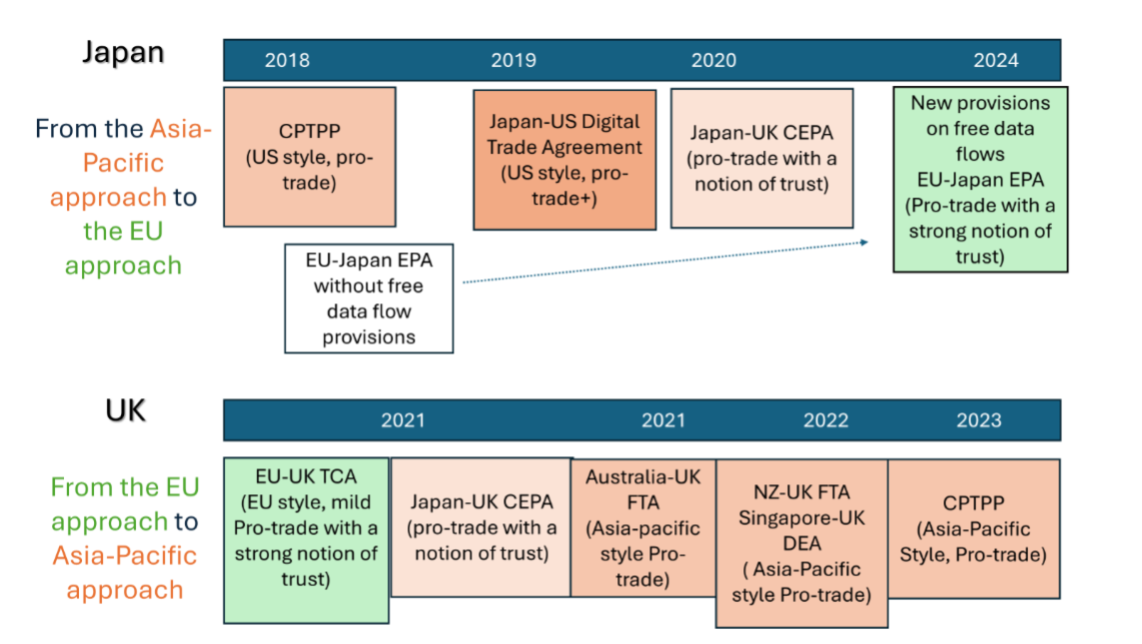

An interesting aspect here is Japan’s policy journey on digital trade agreements, which reflects a shift from the US or Asia-Pacific style pro-trade approach to the EU-style human-centric approach. The starting point of Japan’s policy journey was the CPTPP e-commerce chapter (originally the TPP e-commerce chapter) which strongly reflected US tech-companies’ desire for a laissez-faire international digital environment. The agreement prioritises free data flows with a very narrow public policy space. Under the Japan-US Digital Trade Agreement (DTA), the Japanese government accepted the US approach, which leans even more towards business interests than the CPTPP.

Subsequently Japanese policy preference shifted more towards the EU’s human-centric approach. The Japan-UK Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) signed October 2020, which reflects both the CPTPP and the EU-UK TCA, could be seen as a first step in this direction.

Why the change? At the domestic level, data privacy regimes have been legally and institutionally strengthened over the last decade. At the international level, the Japanese government has been advocating the new norm of “Data Free Flow with Trust” from 2019 through G7, G20, OECD and beyond.[1] The Japanese government considers that the new EU-Japan protocol, incorporating the principle of “DFFT”, will contribute to a more balanced approach to digital trade and could become a model of a 21st century digital trade agreement.

In contrast, the UK’s policy journey has unfolded in the opposite direction (Figure 1). Other than the EU-UK TCA, the UK has tended to depart from the EU style digital governance approach. With the tilt to the Indo-Pacific, the UK has aligned itself more to the Asia-Pacific style market-driven approach to digital trade governance. The digital trade rules under the Australia-UK FTA, UK-New Zealand FTA, and Singapore-UK DEA are modelled on the CPTPP.

Indeed, the Conservative UK government’s efforts to reform of the UK data protection regime (Data Protection and Digital Information Bill), reflects a drift away from EU-style data governance. It has also enabled the UK to strike these digital trade deals. The reforms prioritised data-driven innovation with an ambition of making the UK an international data hub, but legal experts raised concerns over their ethical, social and legal implications.

The Labour Party manifesto was silent about digital trade governance, and the approach of the new government to digital trade is an important question as it will, in part, shape tomorrow’s world.

At the multilateral level, we have entered a new phase of negotiations. It seems that cross-border data flows provisions are being dropped from the on-going WTO Joint Statement Initiative (JSI) negotiations on e-commerce. This is because of the lack of support, if not opposition, from the US as it wants stronger tech regulation. Although there was not a consensus over the balance of free data flows and public policy objectives even before the US’s objections, the US’s position has proved a key obstacle to multilateral rules on data flows. Under such circumstances, promoting a new digital trade model like the EU-Japan new agreement and the UK-EU TCA could help mitigate US’s concerns over limited public policy space.

The quality of the UK’s data governance is ranked as world-leading according to the Global Data Governance Mapping Project. This means that the UK is well positioned to show the best practice to its trade partners while enhancing the trust side of digitisation and promoting digital trade at the bilateral, plurilateral and multilateral levels.

With the new UK government, there is an opportunity to revisit its role at the international level. Given that the Labour government values individual / human rights while promoting innovation, the UK could play an active role in forging a broader consensus on the balance between free data flows and public policy space. As part of it, it seems natural for the UK to collaborate with Japan and the EU to promote the balanced approach achieved under the EU-UK TCA and the EU-Japan EPA. This could help regain support from the US administration for the WTO negotiations and other international forums.

[1] As for “DFFT” and its relation with trade policy, see “Can trade policy enable “Data Free Flow with Trust?“

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher July 23rd, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

June 28, 2024 Anupama Sen is a Research Assistant in International Trade (Economics) at the UKTPO.

Anupama Sen is a Research Assistant in International Trade (Economics) at the UKTPO.

For nearly a decade, China has been the linchpin of global supply chains, thanks to its competitive labour costs and vast manufacturing prowess, earning it a moniker as the ‘factory of the world’. China’s strong manufacturing position extends to the automotive industry. Against that backdrop, starting on 4 July 2024, the EU will implement tariffs, in the form of countervailing duties (CVDs) ranging from 17% to 38%, on Chinese electric vehicles (EVs). These duties on Chinese EV imports will be on top of an existing 10% duty, thereby reaching a peak of 48%. The decision to levy further duties follows an investigation by the European Commission launched in October to investigate Chinese subsidies distorting EV prices and posing unfair competition risks to European carmakers. Thus, the tariffs are applied on a company-specific basis, tailored to the level of subsidies allegedly received by Chinese firms.

The EU’s tariffs on Chinese EVs could be seen as a strategic move aimed at reducing its dependency on China in this sector whilst at the same time stimulating domestic EV production. While some may view this policy as protectionist or neo-mercantilist, it could alternatively be seen as a prudent industrial strategy to foster economic resilience for the EU and to create a level playing field in the global market for EVs. This blog explores the necessity for such a strategy, supported by data illustrating the EU’s growing reliance on Chinese EV imports.

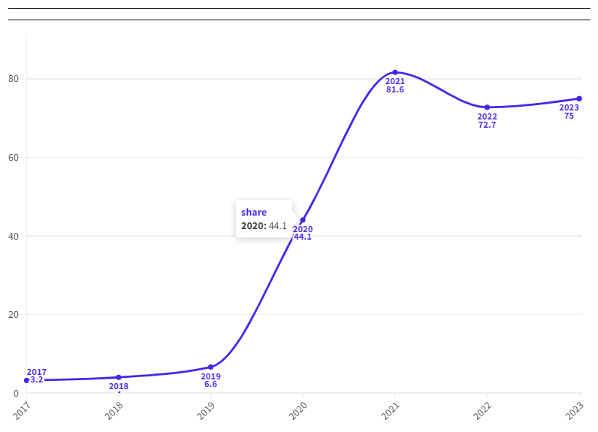

Imports of Chinese produced EVs into the EU market have increased significantly over recent years. Table 1 presents the import values for the car industry and electric vehicles (EVs) from 2017 to 2023, while Figure 1 shows the share of EVs within the total car industry imports. The share of EV’s in total car imports from China rose substantially from 3.2% in 2017 to 81.6% in 2021, with a slight rebound thereafter. While it is difficult to pin down any single specific factor that led to this surge in EV imports in 2021, by then China’s EV industry had grown substantially. This was in part due to substantial state subsidies that enabled manufacturers to offer EVs at competitive prices. Additionally, the EU’s commitment to green energy, including incentives from the 2019 Green Deal, had made the market more receptive to EV imports. Lower trade barriers for Chinese EVs in the EU compared to regions like the U.S. also facilitated this surge. However, EU imports from China have been rising in absolute terms throughout the entire period, in both EVs and non-EVs.

|

Year |

Car Industry (billion USD) HS 8703 |

Electric Vehicles (billion USD, HS 870380) |

|

2017 |

0.46 |

0.01 |

|

2018 |

0.61 |

0.02 |

|

2019 |

1.02 |

0.07 |

|

2020 |

2.06 |

0.91 |

|

2021 |

7.03 |

5.74 |

|

2022 |

9.94 |

7.23 |

|

2023 |

13.96 |

10.47 |

Source: UN Comtrade

Notes: Figures are in billion USD. HS code 870380 refers to: Motor cars and other motor vehicles principally designed for the transport of <10 persons, incl. station wagons and racing cars, with only electric motor for propulsion (excl. vehicles for travelling on snow and other specially designed vehicles of subheading 8703.10).

Source: Author’s Calculation on Import data from 2017 to 2021 using UN Comtrade

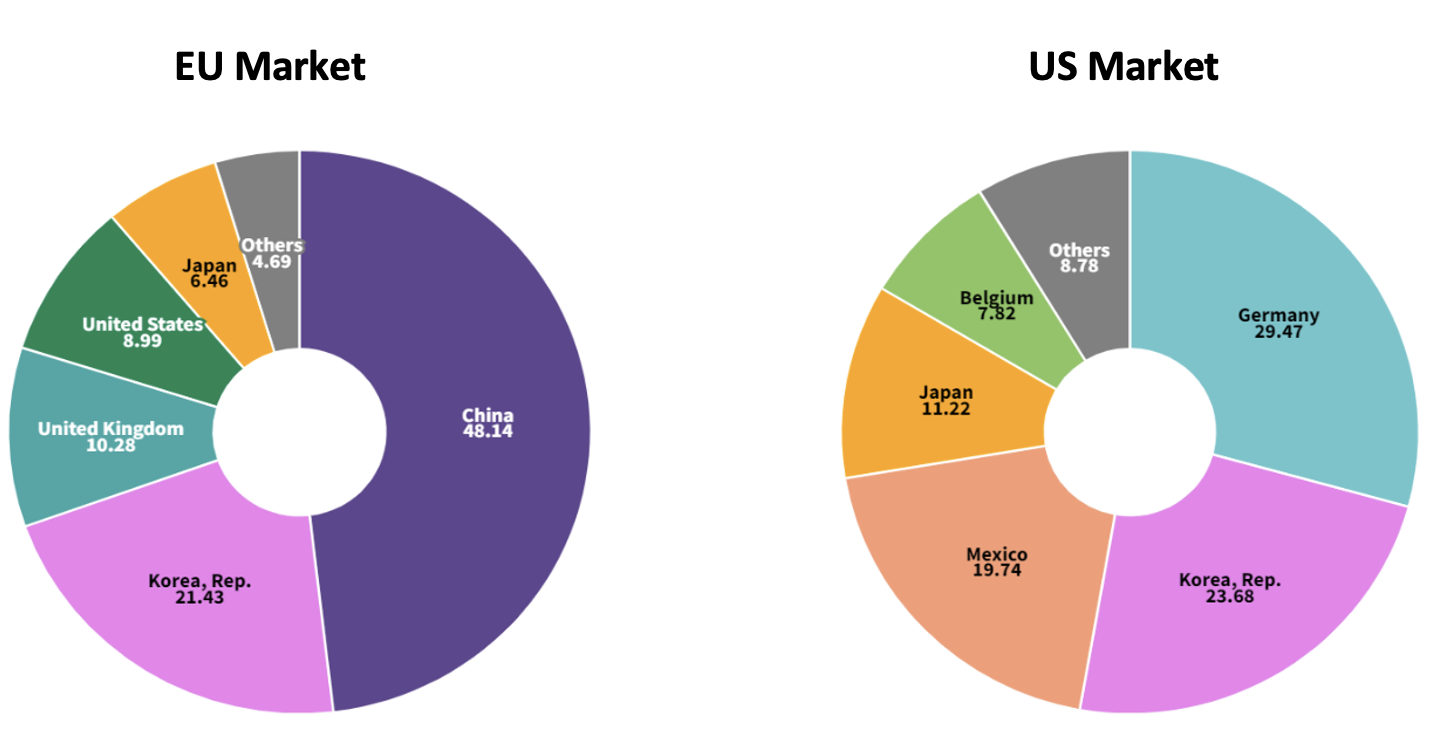

Whereas the EU has implemented tariffs on Chinese EVs in the face of a huge surge in imports, the United States has imposed even higher tariffs of up to 100% on Chinese EV imports despite minimal penetration of these vehicles in its market. Unlike the EU with its heavy reliance on China, the US has diversified its EV supply chain primarily through suppliers in Germany, Korea, and Mexico. This difference underscores how the EU’s approach is potentially consistent with addressing concerns about economic vulnerabilities and promoting local industry growth. In contrast, the US strategy focuses more on safeguarding its existing supply chain diversification.

Figure 2 shows the largest suppliers of EVs to the EU and US markets, respectively. We can observe how heavily reliant the EU is on China as the largest supplier of EVs by a wide margin, whereas the US has been able to diversify its supply chain sufficiently among other exporters.

Source: Author’s Calculation from UN Comtrade Data

Beyond the economic implications, China has complained that the EU duties contravene WTO rules. The WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement) provides the legal framework for these actions, allowing member countries to impose countervailing duties on subsidized imports harming domestic industries. While differentiating duties by firm is common in anti-dumping cases, it is less familiar in the context of subsidies. This differentiation might initially raise concerns about discrimination. Article 15(2) of Regulation (EU) 2016/1037 allows the EU to impose firm-specific countervailing duties. The SCM Agreement’s silence on this practice implies its likely permissibility due to the absence of an express prohibition.

Moreover, the EU’s regulation includes a separate procedure for calculating duties in cases of non-cooperation, potentially resulting in higher tariffs for such firms. Nevertheless, the basis for selecting specific Chinese companies under investigation remains unclear. Chinese firms receive various forms of support, including preferential interest rates, directed credit, tax credits, and cross-subsidies. The methodology for calculating tariffs has only been circulated to the sampled firms thus far. Until the EU publishes its methodology, it is difficult to fully assess the legal validity of the EU’s differentiated tariffs and how subsidies for each firm have been accounted for, as well as the injury to the EU industry caused by each firm.

The EU’s tariffs on Chinese EVs will have varied economic repercussions. They may serve as a catalyst for Chinese manufacturers to relocate production to the EU. For instance, Chinese carmaker BYD has established EV plants in Hungary, and Geely has shifted production to Belgium. This shift has the potential to attract investment, bolster local manufacturing, stimulate job creation, and enhance EU technological capabilities.

However, the immediate consequence of higher tariffs could be increased costs for consumers as part of the tariff rise will most likely be passed on to them. In addition, more protection for EU producers might shift their focus away from innovating and seeking efficiency gains. Finally, the tariffs may strain EU-China trade relations and prompt retaliatory measures.

Imposing tariffs on Chinese EVs may also jeopardize the EU’s ambitious climate goals, as outlined in the European Green Deal. Higher tariffs are almost surely set to slow down EV adoption rates in the EU, delaying the transition away from fossil fuel-powered vehicles and hindering progress towards achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. Additionally, efforts to boost local EV production in response to tariffs may temporarily raise CO2 emissions during manufacturing, particularly in energy-intensive battery production. Striking a balance between trade policies and environmental objectives is crucial to ensure that measures such as CVDs support rather than hinder the EU’s carbonization progress.

As the US and EU pivot away from heavy reliance on Chinese manufacturing, they are integrating ASEAN nations (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam) into their supply networks. These efforts are bolstered by frameworks such as the US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) and the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)[1]. This strategic shift underscores the imperative of diversifying supply chains to enhance economic resilience amidst global uncertainties.

In this recalibration, cultivating strategic partnerships—often termed friendshoring—takes on critical significance. These alliances aim to deepen economic collaboration while mitigating risks associated with overreliance on single suppliers. As part of such initiatives, the EU may aim at strategically diversifying its EV supply chain by investing in economies such as Mexico, Japan, and South Korea, thereby enhancing supply chain resilience and reducing dependency on China. India, with its burgeoning EV market, represents a significant opportunity. Notably, in 2023, India surpassed China in three-wheeler EV sales, underscoring its potential as a key player in the global EV industry[2].

The EU’s impending tariff hike on Chinese EVs presents a complex challenge touching on economic, environmental, and geopolitical dimensions. While aimed at protecting European industries from unfair competition, these measures may strain EU-China relations and potentially undermine the EU’s climate goals. Balancing the need to diversify supply chains with environmental goals and political costs is crucial to mitigate risks and ensure sustainable economic growth.

[1] Neither the EU nor the US are part of CPTPP, even though the agreement is shaped on the provisions negotiated for the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP). This latter was heavily influenced by the US, although it withdrew from it in 2017 and CPTPP came into effect between 11 signatories in 2018. The UK signed an accession protocol in 2023.

[2] https://www.cnbc.com/2024/04/26/india-says-new-ev-policy-will-open-up-market-to-global-players-.html

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 28th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

June 25 2024

June 25 2024

Sahana Suraj is a UKTPO Research Fellow in International Trade.

With less than two weeks until the United Kingdom elects its 59th parliament, campaigning efforts by contesting political parties intensified with the recent publication of party manifestos.[1] The UK is the fourth largest exporter of goods and services, so it is particularly important to shine light on the next government’s stance for developing a robust trade policy that maximises the benefits of trade consistent with domestic policy objectives.

While clearly there is a degree of overlap, the approaches to trade (policy) by the main parties—Conservatives, Labour, Liberal Democrats, Green Party, Reform UK—can be broadly categorised into three different groups.

One group, consisting of the Labour Party and Liberal Democrats, appears to align trade policy with industrial strategy. Concerned with building a resilient and secure economic future, their proposed course of action aims at capitalising on the UK’s existing economic strengths, including in services trade. This approach entails a focus on the depth and quality of agreements, forging strategic partnerships to create a pro-business and pro-innovation environment, and making trade more accessible.

This orientation to trade policy can be characterised as going beyond a conventional focus on Free Trade Agreements (FTAs). Labour, for instance, also recognises the importance of Mutual Recognition Agreements (MRAs) and standalone agreements to promote services trade and digital trade. Agreements of this nature can have strong trade promotion effects and can be effective in reducing non-tariff barriers to trade. The Liberal Democrats have stressed the importance of human rights, labour rights, and environmental standards while negotiating trade deals. This indicates their commitment to using trade policy to achieve benefits in other areas of public policy. They propose renegotiating existing trade agreements with Australia and New Zealand to achieve more favourable outcomes for the UK in health, the environment, and in animal welfare.

Both parties are focused on promoting deeper cooperation in trade policy by expanding markets for British exporters and deepening trade partnerships. Labour also endorse the ongoing FTA negotiations with India and are open to negotiating agreements with the United States and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). Moreover, they recognise the importance of African economies and multilateral institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

Another group consists of manifestos whose approach to trade policy derives from their commitment to sovereignty above all. This includes the Conservatives and to a lesser extent Reform UK. They focus on the imperative for the UK to independently dictate its course on all trade policy matters, as well as protecting the UK’s internal market. The Conservatives propose heavy reliance on FTAs to extend ties to Switzerland, the Middle East (GCC, Israel), Asia (India, South Korea, Vietnam, Singapore, Indonesia) and the United States, the rationale being an expansion of trading relationships post-Brexit. The aim of these agreements is largely to increase cooperation in trade, technology, and defence that will eventually allow the UK to become the largest defence exporter in Europe by 2030. These strategies exemplify their strong emphasis on linking trade policy with economic security.

As part of the focus on sovereignty, the Conservatives and Reform UK both assign importance to agriculture. Ending UK quotas for EU fishers, creating opportunities for the domestic food and drink industry, and recognising the importance of farmers while negotiating FTAs are issues raised by the parties. There are also detailed plans to promote intra-UK trade. While Reform UK proposes a rather radical approach by abandoning the Windsor Framework, the Conservatives recommend the establishment of an Intertrade body to promote Scottish exports and partnerships with British Overseas Territories.

Lastly, the Green Party’s stance on trade policy incorporates elements found in the preceding two groups with policies that encourage trade agreements to take account of worker’s rights, consumer rights, animal protection, and environmental standards, and a traditional focus on agriculture. They advocate the ending of what the party perceives as unfair deals related to food and agriculture and rather place emphasis on encouraging domestic food production.

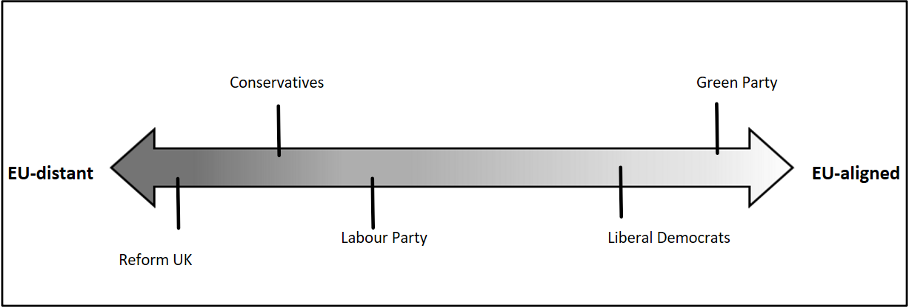

The question of the UK’s future relations with Europe is arguably of central importance from a trade perspective. On this aspect, the parties exhibit much greater divergence between each other, than their general stance on trade. Each of the parties proposes varying levels of engagement with the European Union as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Level of closeness to the EU as proposed by the parties’ manifestos.

Both main parties—the Conservatives and Labour—are against Britain’s return to the European Union. However, they differ on future trade relations with Europe. Labour advocates closer ties with the EU and wants to take advantage of Britain’s geographical proximity to the region. It intends to negotiate a mutual recognition agreement with European counterparts on professional qualifications and services exports. Labour is also in agreement with the EU’s approach to transition to Net Zero by adopting a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), and they aim at negotiating a veterinary agreement with the EU to reduce the burden of border checks.

In contrast, the Conservatives place legal sovereignty above other interests and accept a gradually growing regulatory distance from the EU as a result. They are keen to repeal EU laws that have been transposed into UK law since Brexit and ensure that the EU’s commitments are met under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA). They intend to dub the UK as the largest net exporter of electricity and implement a new carbon import pricing mechanism by 2027.

The position towards the EU of the other parties—Green, Reform, and Liberal Democrats—fall at either end of the spectrum. While Reform staunchly advocates for a complete renegotiation of the TCA and seeks to distance themselves completely from Europe, the Green Party and Liberal Democrats propose an eventual re-integration into the European Union. The Liberal Democrats especially want to align the UK’s and EU’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) and also align the UK’s food standards with that of Europe.

From the outset, trade policy does seem to be on the agenda of contesting parties, albeit still considered in conjunction with Brexit. That being said, there is a significant degree of uncertainty attached to the UK’s future trade policy, as the main parties present starkly opposite proposals on EU relations. And yet, the UK is an open economy that relies on international trade for economic prosperity and jobs. Therefore, the next government’s approach to trade policy and trade governance will matter a great deal, and the more clarity voters have over the parties’ intentions, the better.

[1] Party manifestos can be accessed by visiting the following links:

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 25th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

18 June 2024

18 June 2024

Alasdair Smith is a UKTPO Research Fellow, a researcher within the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP), Emeritus Professor of Economics and Former Vice-Chancellor at the University of Sussex.

The 2019 General Election focused on the one issue of Brexit, and Boris Johnson’s victory enabled the UK to leave the EU. The evidence analysed by UKTPO and many others since then has confirmed the general expectation among expert economists at the time that Brexit would have negative economic effects. And recent opinion poll evidence is that a majority of voters think Brexit was a mistake.

To say that Brexit was a mistake does not imply it could or should be simply reversed. Yet, it is reasonable to expect the political parties to address the issue in their current election campaigns.

The Labour Party’s ambition for the future EU-UK relationship is set out in two paragraphs in their manifesto published on 13 June:

“With Labour, Britain will stay outside of the EU. But to seize the opportunities ahead, we must make Brexit work. We will reset the relationship and seek to deepen ties with our European friends, neighbours and allies. That does not mean reopening the divisions of the past. There will be no return to the single market, the customs union, or freedom of movement.

Instead, Labour will work to improve the UK’s trade and investment relationship with the EU, by tearing down unnecessary [my emphasis] barriers to trade. We will seek to negotiate a veterinary agreement to prevent unnecessary border checks and help tackle the cost of food; will help our touring artists; and secure a mutual recognition agreement for professional qualifications to help open up markets for UK service exporters.”

A firm commitment to stay out of the EU for the next Parliament is surely wise. The UK-EU relationship has been bruised by the experience of the last 8 years. Rebuilding the relationship will take time and patience, and the opportunity to solidify the long-term relationship lies some way in the future. The incoming government faces formidable challenges in many areas and even a long-term plan to rejoin the EU would be a diversion from more immediate priorities.

Since there is no plan to rejoin, it follows that a new government must indeed seek to “make Brexit work”. It’s also right to aim for the removal of any unnecessary border checks and other barriers to trade that have damaged the UK economy.

This is a more positive and less dogmatic approach to the UK-EU relationship than the Conservative manifesto whose main concern is to rule out “dynamic alignment” to EU rules and “submission to the CJEU [the Court of Justice of the EU]”.

Dynamic alignment means sticking to EU rules even when they change. There’ s a strong case for dynamic alignment in many areas, to create a climate of regulatory predictability in place of the regulatory uncertainty and instability of recent years. In any case, firms have to satisfy EU regulations for products they sell in the EU. In many important sectors of the economy (like chemicals and motor vehicles) that means virtually all their production has to meet EU requirements, so separate UK regulations are a deadweight cost.

The Labour manifesto’s red lines are clearly drawn: “no return to the single market, the customs union, or freedom of movement”. The political pressure for such clear lines is understandable. However, they will constrain the objective of reducing border checks and other barriers to trade.

The European single market (which encompasses some non-EU countries like Norway) is the regulatory framework which removes barriers to trade within Europe. Members of the single market adopt common regulations, common processes for assessing conformity with these regulations, and a common legal framework under the umbrella of the CJEU. Members of the customs union similarly have a common policy towards goods imported from non-member countries. Checks on trade between EU countries are unnecessary.

However, if the UK remains outside the single market and the customs union, checks on UK exports to the EU are necessary to make sure that EU rules are satisfied. It’s not enough for UK producers to satisfy EU rules – their products still need to be checked for conformity. However much trust and goodwill are built up with our EU partners and no matter how much alignment there is with EU rules, the scope for removing “unnecessary” barriers to UK-EU trade may be frustratingly limited in practice.

The main political barrier to UK membership of the single market is, of course, the additional single market requirement for the free movement of labour. But post-Brexit restrictions on labour mobility between the EU and the UK has had adverse effects in many important UK sectors: including business services, agriculture, hospitality, social care, and the creative industries.

It’s understandable that the Labour manifesto rules out free movement, but notable that it is silent on the recent EU offer on youth mobility: proposals which emphatically do not imply freedom of movement (not least because they involve visa controls). These proposals would restore to young Europeans in the UK and the EU some of what they lost as a result of Brexit, and would also help address some of the problems of the sectors most affected by Brexit. Surely an incoming government should take a more positive approach to the EU offer.

Opinion poll evidence is that a clear majority of the UK electorate favour a return to EU-UK freedom of movement. A new government may find the political constraints changing quite quickly, so that rejoining the single market becomes thinkable.

A manifesto commitment not to rejoin the single market applies to the next Parliament but doesn’t stop the government from preparing to rejoin in the following Parliament. The path to re-entering the single market would in any case be a long one, probably via the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) into the European Economic Area (the EEA). This path requires preparation and negotiation.

That preparation should include addressing the fact that the single market requires free movement of labour not free movement of citizens. The UK could develop rules for a regime in which EEA citizens are not unconditionally free to come to the UK but are free to relocate to the UK (with their families) in order to work.

The Liberal Democrat manifesto, in contrast to the Labour manifesto’s red lines, makes a positive commitment to rejoining the single market:

“Finally, once ties of trust and friendship have been renewed, and the damage the Conservatives have caused to trade between the UK and EU has begun to be repaired, we would aim to place the UK-EU relationship on a more formal and stable footing by seeking to join the Single Market.”

Realistically, the timetable suggested by these words could well extend beyond the 4-5 years of the next Parliament. In this case, the difference between the Labour and LibDem manifestos may be presentational, rather than real. The single market issue will not go away, even if it cannot be settled before another general election at which a proposal to rejoin the single market could be put to the electorate.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 18th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

30 May 2024 – I

30 May 2024 – I

ngo Borchert is Deputy Director of the UKTPO, a Member of the Leadership Group of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and a Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex. Michael Gasiorek is Co-Director of the UKTPO, Co-Director of the CITP and Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex. Emily Lydgate is Co-Director of the UKTPO and Professor of Environmental Law at the University of Sussex. L. Alan Winters is Co-Director of the CITP and former Director of the UKTPO.

ngo Borchert is Deputy Director of the UKTPO, a Member of the Leadership Group of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and a Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex. Michael Gasiorek is Co-Director of the UKTPO, Co-Director of the CITP and Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex. Emily Lydgate is Co-Director of the UKTPO and Professor of Environmental Law at the University of Sussex. L. Alan Winters is Co-Director of the CITP and former Director of the UKTPO.

A general election is underway, and the parties are making various promises and commitments to attract voters, and both the main parties – the Conservatives and Labour – are keen to persuade the country that they have a credible plan. Now it might just be that the authors of this piece are trade nerds, but one key aspect of economic policy has not yet been clearly articulated, or even mentioned – and that is international trade policy.

In our view, this is a mistake. As a hugely successful open economy, international trade constitutes a significant share of economic activity, supports over 6 million jobs in the UK, spurs innovation, and enhances consumption choices. In short, trade and investment flows are an important element in leading to higher economic growth and welfare. In addition, trade and investment relations intertwine considerably with increasingly fraught geopolitics. Against this backdrop, the UK cannot afford to give trade policy short shrift.

Admittedly, though, trade policy is complex. It is also, more than ever, linked to other dimensions of public policy – and that does make it harder to have simple soundbites. That is no doubt part of the explanation why trade hasn’t been mentioned. The other part is that discussions of trade policy are closely intertwined with the ‘B’ (Brexit) word, and those discussions have become somewhat toxic.

Nevertheless, we argue that sound trade policy is a high priority for the UK. Listed below are some practical, feasible, and specific policy proposals that would help to ensure a better and more coherent UK trade policy, and thus lead to more equity in trade outcomes as well as higher rates of economic growth for the UK.

Process and consultation

1. Publish a Trade Strategy, which should elucidate principles as well as concrete policy objectives and intentions. Recognise the importance of both goods and services trade policy for the UK economy, nationally and across the regions.

2. Reduce executive power over trade policy, through establishing an independent Board of Trade, strengthening Parliamentary oversight over Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and improving consultative processes with devolved nations and with stakeholders in trade.

3. Ensure and commit to transparency in UK trade data, good access to data for researchers and be transparent about the analyses undertaken by government.

Policy Areas:

4. Plurilateral / Multilateral / World Trade Organization (WTO):

a. Ensure that UK trade policy remains consistent across its various partner countries and across the different free trade agreements notably with regard to regulatory approaches.

b. Ensure that trade policy supports the rules of the multilateral trading system. Work on policy areas, such as supply chain security, bilaterally and multilaterally in ways which are at a minimum consistent with this, if not designed to strengthen multilateral cooperation.

c. In the absence of an effective WTO dispute settlement mechanism, join the Multi-party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA).

5. Bilateral trade relations:

a. Do not expect too much from further, notionally comprehensive, free trade agreements with more countries. Focus more on improving the workings and utilisation of existing agreements.

b. Work to reduce costs of trade with the EU in both goods and services, e.g. by mutual recognition agreements on standards, qualifications and certification and negotiating an EU-wide youth mobility scheme. As a first step seek a veterinary agreement.

c. Seek to cooperate with the EU on environmental regulation that impacts upon trade, most immediately by linking ETS schemes with the EU and introducing a compatible CBAM.

d. Review rules of origin with the EU and seek improvements where there may be benefits to both parties (eg. Electric vehicles and car batteries).

6. Domestic:

a. Provide better resourcing and introduce more robust border checks to uphold the UK’s high food standards and prevent the introduction of pest and animal diseases.

b. Work closely with industry to make sure that the implementation of new border arrangements, including the Border Target Operating Model and the Windsor Framework/UK internal market, are understood by businesses and don’t create perverse incentives to UK internal trade, imports or exports. SMEs are likely to face particular challenges.

c. Have a clear digital strategy which deals both with the digitisation of trade transactions and processes, and the rise in digital trade. This strategy should set out the balance of objectives with regard to consumer protection, cyber security, and competitiveness.

This is by no means intended as a comprehensive list, but focusses on some key principles, and specific priorities which are feasible, would make a difference, and could be immediately focussed on. When the manifestos are published it will give an opportunity to assess the parties’ approaches to trade policy and to see whether proposals go beyond broad statements of intent by providing practical details and commitments in line with any of the above.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher May 30th, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

Tags: Brexit, General Election 2024, trade policy, UK Election