8 November, 2024 – David Henig is the Director of the UK Trade Policy Project at the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE).

8 November, 2024 – David Henig is the Director of the UK Trade Policy Project at the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE).

Just for a short time, all went quiet in the UK trade world. A Labour government meant the end of Conservative traumas over EU relations regularly resurfacing. President Biden didn’t do trade deals with anyone, and new UK Ministers made few swift decisions. Meanwhile, the EU reset has been more about smiles than substance.

To be fair, that wasn’t going to last. Though the secrecy instincts of Whitehall linger with a new government, there isn’t much point in a trade strategy shaped without extensive external input and some controversy over decisions. This will need to happen at some point (whether before or after publication) and is an inevitable consequence of choosing priorities.

Similarly, judging by ministerial visits, the only trade deal close to conclusion is with the Gulf Cooperation Council, which if agreed is likely to prove controversial, perhaps in terms of labour and environmental provisions, as well as making only a limited contribution to growth. Meanwhile, arguments over the level of ambition shown in the UK-EU reset are intensifying, as UK stakeholders advocating for ambition increasingly hear frustration from their contacts in Brussels.

President Trump’s re-election changes everything. Trade is a significant part of his agenda, specifically raising tariffs – which we know to be economically damaging. Suddenly commentators are talking about trade again, specialists are being invited to offer their views, and ministers are expected to give answers. Some raise the spectre of a 1930s-style trade meltdown or, more realistically in an age of international supply chains, of interlinked trade wars.

Around two-thirds of UK trade takes place with the US or EU, and these relationships are up for grabs. They are also interrelated in what we could call a new ‘great game’ between those two and the other major powers of world trade: China certainly, and India arguably. This is the geopolitics which the middle powers including the UK, Canada, Japan, and Mexico will need to navigate.

Starting with the basics of Trump’s plans, what is most discussed is a tariff on all goods imports, of 10-20%, with those from China charged higher at around 60%. There is no clarity as to whether this comes on top of MFN levels or not, and that probably doesn’t matter. This seems highly unlikely to be implemented.

Given that a large proportion of imports will be intermediate goods, and others, final consumer goods with no immediately available domestic substitutes, such a policy would be immediately economically damaging to the US. Large companies based in the US will already be making their cases for exemptions, and what we are more likely to see will be targeted or used as bargaining leverage.

More likely is the US starting a series of individual trade conflicts which need to be considered separately, but which could add up to potentially considerable economic damage. Given the integrated nature of global supply chains, it is hard to quantify that with any accuracy, but it will require constant UK government attention to manage.

The UK is likely to be affected in at least three ways: it is a flagrant breach of WTO rules, about which we generally care quite deeply. It may also lead to a global trade war. Finally, the US is our largest single trade partner.

Taking the last first, on UK figures only 30% of our exports to the US are goods. Yet that is still £59 billion, a little under 15% of our goods total. Our sales of whisky, Rolls Royce engines or medicines may well be at risk. No government can ignore this, and doubtless officials have prepared plans for retaliatory measures if necessary. Of course, there will also be talks of a deal, either a full trade agreement or something more partial. Trump is more of a deal-maker than Biden, but anything substantive would probably once again become stuck on agricultural standards on which UK and US approaches seem irreconcilable.

On the second, the UK has so far stood aside from trade conflicts with China. This may become increasingly difficult as the threatened Trump tariffs may be used as leverage for the UK to align more with the US against China. Equally Trump’s tariffs may also lead to EU-US conflict, with the UK as residual damage, or many other permutations. This won’t be a good time for investor certainty.

For world trade rules it is hard to be positive, and maintaining broad agreement outside of the US would seem to be the best case. This will not be a conducive environment for WTO reforms and new plurilaterals, such as on e-commerce. Survival will be the name of the game.

The UK response should be different this time. Unequivocally the UK government will ideally declare a continued commitment to fair global trade rules. Under Trump’s first Presidency there were suspicions that this would be abandoned if the US offered any kind of bilateral deal, which increased suspicion globally without any evident upside. It should also work hard with other like-minded middle powers to counterbalance Trump-induced turbulence.

Various commentators have suggested that the UK government acts as an honest broker between the US and EU, or perhaps trade one off against the other. These should be rejected as not credible. We are novices in the world of trade negotiations, and this will be a battle of heavyweights in which our goal should be not to be crushed by either. It is far better to try to stay out of the fray as much as possible.

Others have seen the election of President Trump as the perfect opportunity for the UK to get closer to the EU, and for the government to put energy into a reset that already shows signs of losing momentum. For some supporters, there will also be the fear of the US pressuring the UK to choose which rules we follow.

What should be the principle here is to follow the money, or rather the main trade flows. With around half our trade, the EU relationship is far more important than that with the US. That’s even been recognised by Robert Lighthizer – USTR under the first Trump term and still close to the President.

Such a commitment isn’t absolute, where the UK can be a rule setter as in financial services, we should do so. For goods, if we have to be followers, the EU is the better model. This makes more economic sense, similarly on climate change measures where we have broad political agreement. There’s no doubt that it is in the UK’s economic interests to seek smoother trade with the EU, but ideally, that shouldn’t come at the expense of wider trade to which we remain committed.

Trade policy is back, it hardly went away in truth. However, in starting with a realistic view of the world, this UK government is better prepared. That needs now to extend to thinking through the limits of what’s possible, in bilateral and multilateral terms. In some ways, it will be every country for themselves. In others, there will be a lot of coordination and discussion. Setting out a clear path in public – one that includes respect for global rules, open trade, and follows our main economic interests – would be a very good start in responding to the new times.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher November 8th, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

25 October 2024 – Erika Szyszczak is a Professor Emerita and a Fellow of the UKTPO. Will Disney is a sustainability researcher and independent consultant.

25 October 2024 – Erika Szyszczak is a Professor Emerita and a Fellow of the UKTPO. Will Disney is a sustainability researcher and independent consultant.

The European Union is using trade measures to achieve a host of policies – climate change, human rights, labour standards – but for one policy area the EU has been hit by a global backlash. Voices within and outside of the EU are calling for a delay, and a re-appraisal, of its ground-breaking anti-deforestation Regulation which came into force on 29 June 2023. The EU has been forced to consider delaying the implementation of the Regulation by 12 months (until 30 December 2025) for large operators and traders. It has also been delayed for micro and small enterprises: until 30 June 2026.

The Regulation aims to promote ‘deforestation-free’ products and reduce the EU’s impact on global deforestation and forest degradation, as part of the action plan embracing the European Green Deal, the EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 and the Farm to Fork Strategy. Firms trading in the EU have been preparing for the full implementation of the Regulation by exercising due diligence in their value chains. This has been done to ensure that any trading in cattle, cocoa, coffee, oil palm, rubber, soya and wood, as well as products derived from these commodities, does not result from any deforestation, forest degradation or breaches of local environmental and social laws that occurred from 31 December 2020. However, tracing supply chains in a global economy is difficult, and the Regulation is complex. The European Commission only published guidance on the Regulation on 2 October 2024. This guidance does not provide a steer on which non-EU countries may be seen as high risk, indicating where greater due diligence should be exercised. It only presented the methodology that will be used to benchmark countries and regions in terms of their deforestation risk. Thus, the Regulation will introduce new and onerous customs checks, creating new technical barriers to trade.

The responsibility to ensure compliance with the Regulation lies with the firm placing relevant products on the EU market or exporting such products from this market. Failure to comply will result in penalties: potential fines of up to 4% of the firm’s EU turnover, and confiscation or exclusion from public funding or contracts. Penalties for non-compliance will be set under national law. However, it is anticipated that breaches of the EUDR will lead to criminal penalties.

The Regulation has not garnered total support even within the EU. Requests to postpone the operation of the Regulation emerged from the United States, fearing shortages of sanitary products. The WTO Director General, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, called for a delay and reappraisal of the law, especially in light of developing countries seeing the Regulation as lacking an understanding of land use and the costs and expertise needed to map land use.

As such, the Regulation is viewed by some as being discriminatory and punitive towards the global south. Certainly, the Regulation creates new technical barriers to trade, with criticisms that its compliance requirements are “overburdensome and ill-defined.”

Musdalifah Machmud, the former Indonesian Deputy Minister at the Coordinating Ministry for the Economy (now Expert Staff for Connectivity, Service Development, and Natural Resources), sees the Regulation as taking a derogatory attitude towards attempts in the global south to counter de-forestation, and makes this appeal:

“… Indonesia’s efforts on deforestation, its environmental reforms and its certification systems must be recognised within the EUDR and by European stakeholders more broadly.

Indonesia’s deforestation rates are now at their lowest on record, and 90 per cent below their peak a decade ago. The tired narrative of Indonesia – and its commodity producers – as environmental vandals must be dispensed with.”

When the EU adopted the Regulation, it was motivated by environmental concerns. Yet, could it be seen as another example of geoeconomics where the EU is protecting its political and economic interests? Is the EU forging a new framework to control supply chains and define its responses to global threats in international trade? Is this another example of the EU extending its extra-territorial reach into the economies of third states?

Despite resistance from both the public and private spheres, there are also loud voices supporting the Regulation. A coalition of cocoa companies including Nestlé, Ferrero, Mondelēz, Mars, Tony’s Chocolonely and NGOs such as the Rainforest Alliance and Solidaridad, “strongly oppose” calls to reopen the substance of the EUDR.

Stakeholders argue that any renegotiation or further delays will hinder the ability of firms and suppliers to shape business activities to address and report on this complex issue.

Data from the World Benchmarking Alliance’s (WBA) Nature benchmark, an NGO that measures companies’ impact on nature and biodiversity topics, highlights only 7% of the companies currently publicly disclose where their suppliers are based. Beyond resistance from companies to report on this issue, this low figure can also be attributed to the lack of a globally recognised framework to disclose on the topic.

The EU has been criticised for its lack of support for affected stakeholders, particularly regarding the delay in the lack of clarification and guidance on the exact systems which should be implemented to satisfy the Regulation.

The EU must create roadmaps and provide more clarity around the expectations of firms headquartered in the EU, as well as explain the support they should provide to suppliers during the transition. For example, helping suppliers by covering the costs of obtaining certifications for globally recognised sustainability standards.

The consequences of not implementing the policy could be substantial. Analysis from the NGO Global Witness suggests that even a 12-month delay could lead to 150,385 hectares of deforestation linked to EU trade, an area more than fourteen times the size of Paris. Therefore, EU regulators must act urgently if the EU is to avert CO2 emissions related to its market and trade and, ultimately, meet the bloc’s climate goals through the EU Green Deal.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher October 25th, 2024

Posted In: UK- EU

04 October 2024 – Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School.

04 October 2024 – Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School.

The 2024 World Trade Organization (WTO) Public Forum was sure to be a fascinating occasion given the interest in the topic, inclusivity and green trade, and the stellar cast of speakers. But what of the future of the WTO itself? Many observers have come to feel that with the negotiating function and the Appellate Body (AB) both log-jammed, there wasn’t much for the WTO to do apart from hosting events like the Public Forum.

Despite the logjam in negotiations and the apparent death (certainly more than a very deep sleep) of the Appellate Body, the WTO is still delivering value to its members in its routine committee work. It continues to promote transparency etc, and Dispute Settlement Panels still operate, though more like the way they did in the GATT era. Among DS nerds there was sympathy for the idea put forward by Sunayana Sasmal and me[1] that concerns over judicial overreach could be assuaged if the AB (if there were one) could decline to rule if the law was genuinely unclear. But as several Indian experts told us, if there is no AB, it’s not an issue.

Meanwhile, I only found one panel focussing on how to restore negotiations: our very own CITP panel on “Responsible Consensus”, i.e. persuading countries not to use their power to block decisions. It didn’t generate a lot of optimism. India, as well as the US, attracted quite a lot of criticism for its vigorous use of its legal right to veto moves that could affect its interests – even where there was a big majority of supporters. India’s position was elegantly and forcefully explained and defended by Prof Abhijt Das, an old friend of Sussex. He argued that even where other states might want to agree amongst themselves, India had a right to object to Plurilateral deals which might affect them adversely even when no actual obligations were created for them. But, interestingly, despite the delight of seeing many old friends from Delhi, there was little open official Indian engagement. It was striking that the Indian Foreign Minister chose last week to visit Geneva, to consult with UN agencies, but he didn’t visit the WTO. And there was no visible official US profile. On the other hand, China’s CGTN was listed as a Forum sponsor and hosted a lecture by Jason Furman, former senior adviser to Barack Obama. On CGTN, the Chinese DDG Zhang Xiangchen stated how the public Forum, “is a platform for all to make their voices heard” and he “encourages more communication among stakeholders and calls on the active participation of developing countries for a balanced outcome.”

This echoed the message that WTO DG Dr Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala pushed in the sessions she spoke at. It was spelled out in the first ever WTO Secretariat Strategy document.

The WTO Secretariat as a body is seeking to do more than just service the wishes of the Member States. It is seeking to act as a facilitator, convenor and broker, in the absence of, and perhaps to recreate, the missing consensus. Inclusivity and sustainability were being pushed in sessions organised by the Secretariat. The message was that we cannot assume globalisation will benefit everyone without action being taken. This was the underlying theme: the Forum offered Public Diplomacy on behalf of the organisation. Was it just bland PR? One senior legal official told Sunayana and me that the WTO did seem to have found a way to create a new role and a new narrative for itself. The WTO had been very closely involved in the efforts to keep vaccine supply chains and some border crossings open during Covid, at the request of concerned parties and had brokered important agreements. It was “more important than ever”. The Secretariat is beginning to be more proactive and encouraging global dialogue.

Following these conversations, many of the observers we spoke to were somewhat sceptical, but not all. One of the UK’s leading trade specialists thought that this message of pro-active broader engagement was real and had been effective during the COVID period. Dr Ngozi has called for action on carbon pricing in an FT interview. If it could work, seeking to mobilise soft power rather than being the home of rulemaking and rule enforcement would be an excellent strategy. But there are pitfalls. Would it be too controversial in the face of division among members? Is there a risk that the Secretariat could be seen as overreaching its legitimacy in the same way as the Appellate Body? Can the WTO really survive without its key rulemaking and enforcing role? And what if Trump wins?

[1] https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/files/2024/02/Holmes_Sasmal_Not-Liquet-UKTPO-WP.pdf

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher October 4th, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

Tags: WTO

27 September 2024 – Ana Peres is a Lecturer in Law at the University of Sussex and a member of the UKTPO.

27 September 2024 – Ana Peres is a Lecturer in Law at the University of Sussex and a member of the UKTPO.

Lawyers, economists and political scientists are increasingly using a new term to frame discussions on current trade relations and policies: geoeconomics. This means that countries are intervening in strategic economic sectors not primarily for profit but to ensure autonomy, build resilient supply chains and secure access to valuable capabilities. Such approach contrasts with the ideals of free trade, market access and interdependence that shaped international trade for decades. These traditional ideals, even when supported by a so-called ‘rules-based system’, always posed challenges for developing countries to meet their objectives. So, what does geoeconomics mean for developing countries? Unfortunately, it threatens to sideline them even more.

Consider one of the main areas where geoeconomic strategies are at play: the development of clean technologies. Governments are implementing industrial policies to secure access to critical raw materials, an input for electric batteries, and to protect domestic production of electric vehicles (EVs). Such policies often require substantial subsidies. Recent discussions at the WTO Public Forum highlighted that a clear distinction between “bad” and “good” subsidies is not only desirable but essential to deal with many of the new and standing issues in the organisation. Beyond the question of their legality, we need to consider which countries have the financial resources to engage in this new wave of industrial policies – and what happens to those that do not. For instance, the UK’s former Conservative Secretary of State for Business and Trade, Kemi Badenoch MP, stated that the UK government would provide “targeted support (…) looking at what we can afford (…)”. If the UK, as a G7 economy, is concerned about affordability, developing countries face even greater challenges in this context.

An analysis of the proposed “Clean Energy Marshall Plan” suggests that a Harris administration in the US could use industrial policies to make developing countries dependent on US exports of clean technologies. Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) to Latin America is shifting to “new infrastructure” sectors, such as energy transition. The EU signed a memorandum of understanding with Chile to promote sustainable raw materials value chains. All these developments reflect the geoeconomic trend, by prioritizing autonomy, resilience and access for wealthy countries, at the expense of those objectives for poorer countries.

Resource-rich developing countries are not defenceless in this geoeconomic world. For instance, Chile is one of the world’s largest suppliers of lithium (around 80% of all EU imports). The Chilean government’s response, creating the National Lithium Strategy to strengthen control over its reserves and maximise their benefits, offers a glimpse of one path resource-rich developing countries may follow. Similarly, Southeast Asian countries like Indonesia and Malaysia are trying to capitalise on the EV industrial policies of the US and China.

These examples show the power dynamics underlying international trade flows. While geoeconomics brings power and politics to the fore of current trade relations, it does not introduce them to the existing trade order. The process leading to the creation of the WTO and the surge of free trade agreements during the 1980s and 1990s reaffirmed the rule of law as central to promoting trade liberalisation. A rules-based framework should favour the stability and predictability of the global trading system, enabling countries to negotiate new topics and settle trade disputes. However, even in this ‘traditional’ WTO-led approach, law and power are closely linked. Restricting the role of power in trade agreements and institutions does not eliminate it from trade rules and negotiations. Developing countries have long struggled to have their voices heard in trade rulemaking and negotiations. For them, it has always been political.

The novelty of the geoeconomic framework is the recognition that economic and geopolitical powers are intertwined in policymaking. Governments are implementing policies beyond trade, covering areas like environmental protection, defence, health, and digital technologies. Geoeconomics shows how states use their economic and political power to achieve domestic goals and assert or maintain global leadership.

While geoeconomics is useful for describing the current context, it has not yet adequately addressed the position of developing countries. Like many frameworks applied to international trade, geoeconomics explains trade relations and trends from the perspective of the main players. In this case, the US, China and, to a lesser extent, the EU. Tensions between the US and China are driving a new division between allies and adversaries. This raises important questions: who decides which countries are friends or foes? Can – or should – developing countries take sides? What are the potential consequences? Could developing countries leverage the conflict between the world’s two largest economies to strengthen their positions? What will happen to developing countries that are not resource-rich? These will become defining questions for developing countries in the era of geoeconomics.

During the Cold War, the polarisation of global powers led third world nations to advocate for a New International Economic Order. They understood that their interests were sidelined in the global debate driven by ideological and political conflicts between the two superpowers. At the WTO Public Forum, the possibility of “third nations” or “middle powers” guiding multilateral trade efforts was raised, as an alternative to overcome the stalemate created by the clash between the US and China. However, such a heterogeneous group will have to find common ground if they move forward without the two biggest world economies. That is no easy task. This is why including developing countries in discussions about the geoeconomics of trade is so important today – to ensure their concerns are not overlooked or marginalised as they once again risk being caught in the middle of power struggles that threaten to leave them powerless.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher September 27th, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

Tags: Geoeconomics, WTO

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

23 September 2024 – Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School.

23 September 2024 – Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School.

In recent weeks Sir Keir Starmer has visited Germany, France, Ireland and Italy, each in the name, he says, of turning a corner on Brexit, resetting the UK’s relationship with Europe and – most importantly – raising economic growth. The OBR estimates Brexit in its current form to be costing the UK a permanent non recoverable 4% of GDP pa.

So far, the PM’s visits to the EU have been good symbolism. Recent UK opinion polling shows increased public support for building back closer ties with the EU, reflecting that there are many in the UK, including a growing contingent of “Bregretters”, who would like to repair the economic and political damage done since 2016. On the European side the optics of welcome have been decently warm, although perhaps this is not so very surprising after almost ten years of dealing with EU-shy Conservative governments.

However, it is quite striking that, at the time of writing, Starmer has not yet made a visit to Brussels. He may be waiting for Ursula von der Leyen to launch her second term Commission. However, his absence to date has been noted at the Berlaymont and his immediate rebuff of an EU proposal for a youth mobility scheme went down badly. EU officials are reported to be asking how serious about a Brexit reset he really is. There is doubt he has a clear strategy beyond his “red lines”[1].

While the new Commission awaits final confirmation, the UK has a breathing space which it can use to clarify its own strategy. But by the time the new Commission starts to plan its five-year agenda, in early 2025, the UK needs to have put together a clear proposal for the EU to react to. To be good enough to deliver an economic upturn for Britain, it will have to be more than just a few cherry-picked ideas and restatement of what the UK doesn’t want.

But even as he enthused about a bilateral deal with Germany on his Berlin trip, Starmer doubled down on his red lines of “no single market”, “no customs union” and “no rejoining the EU within his lifetime”. If he intends to stick to these red lines, he may find they hinder his goal to boost the UK economy, a point also made by the Resolution Foundation.[2]

EU officials have always insisted that the first requirement for improved relations with the UK would be a renewal of trust, and a willingness by the UK to adhere to the commitments it made in Boris Johnson’s 2020 hurried and flawed “get Brexit done” deal – the treaty formally known as the Trade & Co-operation Agreement (TCA).

The TCA is due for its first 5 yearly review in 2026. Although the EU has repeatedly made clear that they do not want to review the body of this agreement, the treaty does contain provisions for modifying some of its rules without modifying the treaty itself or making a new one. For example, the TCA Title X provides for “Regulatory Co-operation” which would allow UK and EU regulators to discuss and agree potential areas of joint interest, with a fairly open-ended agenda, and it includes concrete provisions for cars, aviation and medicines in annexes. They could then extend the models in other areas. Similarly, the UK-EU Joint Partnership Council which oversees the treaty can agree to change the rules of origin, and has already done so for electric vehicles.

Ahead of the 2026 review the EU has made it clear that the original Barnier red line of “no cherry-picking” no longer apply. Side agreements or “mini-deals” can be signed at any time. Their youth mobility proposal[3], for now declined, was a mini-deal and they have also proposed an SPS [4] mini-deal which would allow meat, fruit and vegetables and flowers to move between the UK and the EU more quickly. To get recognition of our food safety rules we need to make binding commitments to total equivalence, (including how we check third country imports). The British ambition of a comprehensive agreement on Mutual Recognition on Conformity Assessment is unrealistic. Piece by piece might work, including rejoining EU regulatory agencies as associates, eg EFSA and EASA.[5] There is scope for the signature of new UK-EU mini-deals on a range of topics including carbon pricing, aerospace and mutual recognition of professional qualifications. These could require formal endorsement by the Council of Ministers and even possibly the European Parliament, but they are a key avenue to explore. The UK government is placing its hopes in a deal on defence and security, which, although contrary to the Conservatives’ views, Labour hopes will have the broadest economic security dimension.

The UK also has the option to voluntarily match certain EU rules, to ease the burden of compliance on UK businesses. Known as “voluntary dynamic alignment”, it could be a useful approach in principle. It could also help reduce paperwork and the number of border checks faced by UK goods going into the EU. However, this would not eliminate paperwork and checks entirely – in order to do so, we would need to rejoin the EU or at least something like the EEA. On CBAMs, UK firms are unlikely to face any charges if the UK voluntarily aligns fully with the EU. However, unless we agree to be legally bound to apply ETS rules and carbon prices virtually to the EU’s (including coverage and how we have treated third country good that may enter value chains), UK firms will be subject to the need to prove compliance. It may be that the UK way of treating electricity in the ETS might be better than the EU’s plan but this is unlikely to be worth facing the CBAM process.

Often performative divergence such as the UKCA or UK REACH regimes, in the name of “sovereignty” deliver nothing to business except regulatory duplication. The gains to admitting the need to follow the “Brussels Effect” will be at least as much domestic, simplifying business and generating certainty that is needed to restore investment. However, the EU will not automatically recognise the validity of our rule enforcement, even though we have no choice but to accept EU quality certification. An EU negotiator said to me: “We’ll be like India”, i.e. tough on the UK. And they will get to pick more cherries than the UK.

As David Henig[6] points out, there is still appetite on the EU side for a better relationship. Yet, for the UK to benefit, it will need to be prepared to negotiate in all of the above areas. As part of quickly pulling together a new strategic plan, the UK must figure out what it can offer that the EU wants. At the same time, the UK must decide on its own top aims; identify where it can make offers that cost little but will show goodwill; and consider what it is prepared to give up, even though there may be some gain from regulatory autonomy in that sphere. It will not be all or nothing, but there has to be a package.

Unfortunately, the improvements to Brexit that would make the biggest and quickest difference for the UK’s economy are the ones that are currently off-limits, behind Starmer’s red lines. This does not mean the UK can’t do anything at all. There is some low-hanging fruit, including some sort of youth mobility deal. But to make a big difference in reducing border frictions and the uncertainty created by Brexit, the UK will have to go further than Starmer is willing to admit. Making this policy flex work is going to require engaging with the public openly. He could even try one of his now-familiar messages, along the lines of “the Brexit situation was a lot worse than we thought”.

The new EU Commission will start in January 2025. By that time, it would make sense to have dispel any doubts about the UK’s commitment to improved relations, and to be ready – after considering what the UK can offer the EU – to put some attractive proposals on the table. If we take the lead and find areas of mutual interest that generate visible benefits quickly, we can create the political momentum to go further.

[1] Poltiico https://www.politico.eu/article/keir-starmer-european-union-brexit-relationship-reset/?

[2] https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2024/09/Growth-Mindset.pdf

[3] See https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/sep/20/eu-youth-mobility-proposal-uk

[4] Sanitary and Phyto Sanitary ie Food safety.

[5] European Aerospace Safety Agency, European Food Safety Authority.

[6] https://ecipe.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/ECI_24_PolicyBrief_17-2024_LY04.pdf

Peter Holmes would like to thank Karen Triggs for her support in creating this blog post.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher September 23rd, 2024

Posted In: UK- EU

23 July 2024

23 July 2024

Minako Morita-Jaeger is Policy Research Fellow at the UK Trade Policy Observatory, a researcher within the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and Senior Research Fellow in International Trade in the Department of Economics, University of Sussex. She currently focuses on analysing UK trade policy and its economic and social impacts.

The UK is a services economy which accounts for 81% of output (Gross Value Added) and 83% of employment.UK services exports (£470 billion in 2023) are the world’s second largest after the US and 75% of its services exports are digitally delivered. The UK is ranked as world-leading in terms of data governance. Under the new Labour government, it is time to take the initiative on data flow governance at the global stage to achieve a sustainable and accountable digital environment. With the set back in the US negotiations on free data flows at the WTO, the UK can take the initiative to collaborate with the EU and Japan.

The EU-Japan EPA, which entered into force in 2019, lacked provisions on free data flows and personal data protection. This has now been addressed with the signing of the new protocol on 31 January this year which is incorporated into the EU-Japan EPA. The new EU-Japan protocol can be seen as game changers. First, they strike a balance between free data flows and legitimate public policy objectives. Under Article 8.81, measures that prohibit or restrict cross-border data flows, such as localisation requirements of computing facilities or network elements, are restricted. These provisions are similar to the existing digital trade provisions under FTAs/digital trade agreements led by the Asia-Pacific countries, such as the CPTPP.

Yet a significant difference with the Asia-Pacific style FTAs is the scope and definition of “legitimate public policy objective” (Art. 8.81.3 and its footnotes). The new protocol reflects the EU’s approach under the UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) which provides more detail compared to the Asia-Pacific led digital trade agreements.

Another striking difference is that personal data protection is set as a fundamental right. The provisions regarding cross-border data transfers go together with the new provisions regarding protection of personal data (Art. 8.82). The clause is comprehensive and could be seen as the highest standard among existing digital trade agreements, including the EU-UK TCA. It underlines the importance of maintaining high standards of personal data protection to ensure trust in the digital economy and to develop digital trade. Such deep commitments between the EU and Japan were enabled by ongoing policy dialogues, including the EU-Japan Digital Partnership Council.

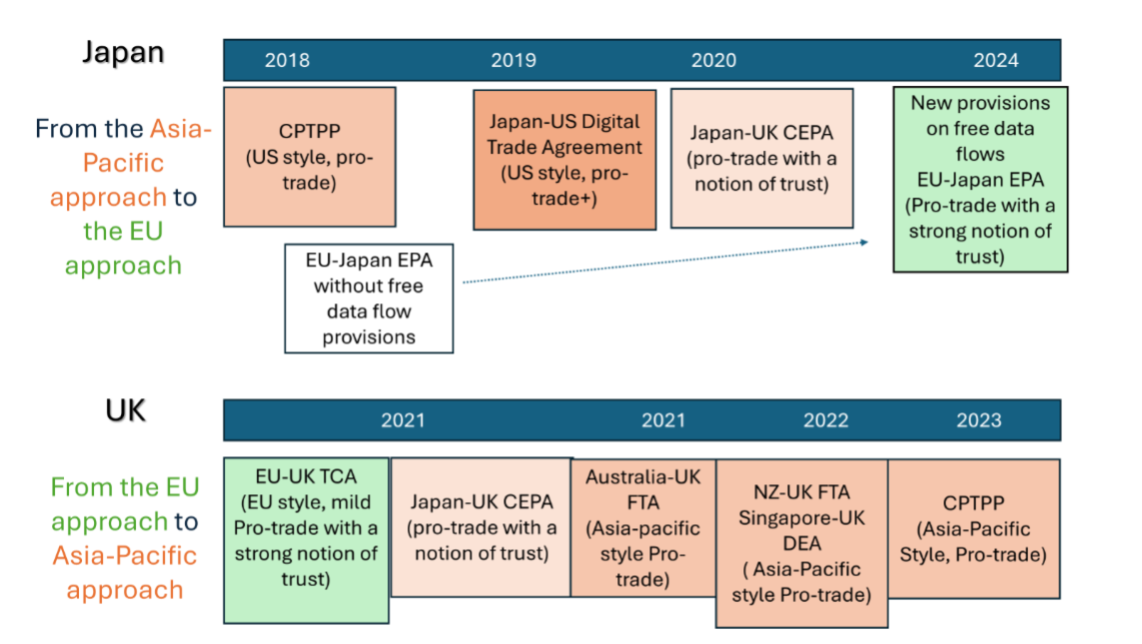

An interesting aspect here is Japan’s policy journey on digital trade agreements, which reflects a shift from the US or Asia-Pacific style pro-trade approach to the EU-style human-centric approach. The starting point of Japan’s policy journey was the CPTPP e-commerce chapter (originally the TPP e-commerce chapter) which strongly reflected US tech-companies’ desire for a laissez-faire international digital environment. The agreement prioritises free data flows with a very narrow public policy space. Under the Japan-US Digital Trade Agreement (DTA), the Japanese government accepted the US approach, which leans even more towards business interests than the CPTPP.

Subsequently Japanese policy preference shifted more towards the EU’s human-centric approach. The Japan-UK Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) signed October 2020, which reflects both the CPTPP and the EU-UK TCA, could be seen as a first step in this direction.

Why the change? At the domestic level, data privacy regimes have been legally and institutionally strengthened over the last decade. At the international level, the Japanese government has been advocating the new norm of “Data Free Flow with Trust” from 2019 through G7, G20, OECD and beyond.[1] The Japanese government considers that the new EU-Japan protocol, incorporating the principle of “DFFT”, will contribute to a more balanced approach to digital trade and could become a model of a 21st century digital trade agreement.

In contrast, the UK’s policy journey has unfolded in the opposite direction (Figure 1). Other than the EU-UK TCA, the UK has tended to depart from the EU style digital governance approach. With the tilt to the Indo-Pacific, the UK has aligned itself more to the Asia-Pacific style market-driven approach to digital trade governance. The digital trade rules under the Australia-UK FTA, UK-New Zealand FTA, and Singapore-UK DEA are modelled on the CPTPP.

Indeed, the Conservative UK government’s efforts to reform of the UK data protection regime (Data Protection and Digital Information Bill), reflects a drift away from EU-style data governance. It has also enabled the UK to strike these digital trade deals. The reforms prioritised data-driven innovation with an ambition of making the UK an international data hub, but legal experts raised concerns over their ethical, social and legal implications.

The Labour Party manifesto was silent about digital trade governance, and the approach of the new government to digital trade is an important question as it will, in part, shape tomorrow’s world.

At the multilateral level, we have entered a new phase of negotiations. It seems that cross-border data flows provisions are being dropped from the on-going WTO Joint Statement Initiative (JSI) negotiations on e-commerce. This is because of the lack of support, if not opposition, from the US as it wants stronger tech regulation. Although there was not a consensus over the balance of free data flows and public policy objectives even before the US’s objections, the US’s position has proved a key obstacle to multilateral rules on data flows. Under such circumstances, promoting a new digital trade model like the EU-Japan new agreement and the UK-EU TCA could help mitigate US’s concerns over limited public policy space.

The quality of the UK’s data governance is ranked as world-leading according to the Global Data Governance Mapping Project. This means that the UK is well positioned to show the best practice to its trade partners while enhancing the trust side of digitisation and promoting digital trade at the bilateral, plurilateral and multilateral levels.

With the new UK government, there is an opportunity to revisit its role at the international level. Given that the Labour government values individual / human rights while promoting innovation, the UK could play an active role in forging a broader consensus on the balance between free data flows and public policy space. As part of it, it seems natural for the UK to collaborate with Japan and the EU to promote the balanced approach achieved under the EU-UK TCA and the EU-Japan EPA. This could help regain support from the US administration for the WTO negotiations and other international forums.

[1] As for “DFFT” and its relation with trade policy, see “Can trade policy enable “Data Free Flow with Trust?“

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher July 23rd, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

30 May 2024 – I

30 May 2024 – I

ngo Borchert is Deputy Director of the UKTPO, a Member of the Leadership Group of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and a Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex. Michael Gasiorek is Co-Director of the UKTPO, Co-Director of the CITP and Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex. Emily Lydgate is Co-Director of the UKTPO and Professor of Environmental Law at the University of Sussex. L. Alan Winters is Co-Director of the CITP and former Director of the UKTPO.

ngo Borchert is Deputy Director of the UKTPO, a Member of the Leadership Group of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and a Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex. Michael Gasiorek is Co-Director of the UKTPO, Co-Director of the CITP and Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex. Emily Lydgate is Co-Director of the UKTPO and Professor of Environmental Law at the University of Sussex. L. Alan Winters is Co-Director of the CITP and former Director of the UKTPO.

A general election is underway, and the parties are making various promises and commitments to attract voters, and both the main parties – the Conservatives and Labour – are keen to persuade the country that they have a credible plan. Now it might just be that the authors of this piece are trade nerds, but one key aspect of economic policy has not yet been clearly articulated, or even mentioned – and that is international trade policy.

In our view, this is a mistake. As a hugely successful open economy, international trade constitutes a significant share of economic activity, supports over 6 million jobs in the UK, spurs innovation, and enhances consumption choices. In short, trade and investment flows are an important element in leading to higher economic growth and welfare. In addition, trade and investment relations intertwine considerably with increasingly fraught geopolitics. Against this backdrop, the UK cannot afford to give trade policy short shrift.

Admittedly, though, trade policy is complex. It is also, more than ever, linked to other dimensions of public policy – and that does make it harder to have simple soundbites. That is no doubt part of the explanation why trade hasn’t been mentioned. The other part is that discussions of trade policy are closely intertwined with the ‘B’ (Brexit) word, and those discussions have become somewhat toxic.

Nevertheless, we argue that sound trade policy is a high priority for the UK. Listed below are some practical, feasible, and specific policy proposals that would help to ensure a better and more coherent UK trade policy, and thus lead to more equity in trade outcomes as well as higher rates of economic growth for the UK.

Process and consultation

1. Publish a Trade Strategy, which should elucidate principles as well as concrete policy objectives and intentions. Recognise the importance of both goods and services trade policy for the UK economy, nationally and across the regions.

2. Reduce executive power over trade policy, through establishing an independent Board of Trade, strengthening Parliamentary oversight over Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and improving consultative processes with devolved nations and with stakeholders in trade.

3. Ensure and commit to transparency in UK trade data, good access to data for researchers and be transparent about the analyses undertaken by government.

Policy Areas:

4. Plurilateral / Multilateral / World Trade Organization (WTO):

a. Ensure that UK trade policy remains consistent across its various partner countries and across the different free trade agreements notably with regard to regulatory approaches.

b. Ensure that trade policy supports the rules of the multilateral trading system. Work on policy areas, such as supply chain security, bilaterally and multilaterally in ways which are at a minimum consistent with this, if not designed to strengthen multilateral cooperation.

c. In the absence of an effective WTO dispute settlement mechanism, join the Multi-party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA).

5. Bilateral trade relations:

a. Do not expect too much from further, notionally comprehensive, free trade agreements with more countries. Focus more on improving the workings and utilisation of existing agreements.

b. Work to reduce costs of trade with the EU in both goods and services, e.g. by mutual recognition agreements on standards, qualifications and certification and negotiating an EU-wide youth mobility scheme. As a first step seek a veterinary agreement.

c. Seek to cooperate with the EU on environmental regulation that impacts upon trade, most immediately by linking ETS schemes with the EU and introducing a compatible CBAM.

d. Review rules of origin with the EU and seek improvements where there may be benefits to both parties (eg. Electric vehicles and car batteries).

6. Domestic:

a. Provide better resourcing and introduce more robust border checks to uphold the UK’s high food standards and prevent the introduction of pest and animal diseases.

b. Work closely with industry to make sure that the implementation of new border arrangements, including the Border Target Operating Model and the Windsor Framework/UK internal market, are understood by businesses and don’t create perverse incentives to UK internal trade, imports or exports. SMEs are likely to face particular challenges.

c. Have a clear digital strategy which deals both with the digitisation of trade transactions and processes, and the rise in digital trade. This strategy should set out the balance of objectives with regard to consumer protection, cyber security, and competitiveness.

This is by no means intended as a comprehensive list, but focusses on some key principles, and specific priorities which are feasible, would make a difference, and could be immediately focussed on. When the manifestos are published it will give an opportunity to assess the parties’ approaches to trade policy and to see whether proposals go beyond broad statements of intent by providing practical details and commitments in line with any of the above.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher May 30th, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

Tags: Brexit, General Election 2024, trade policy, UK Election

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() 22 May 2024

22 May 2024

David Henig is Director of the UK Trade Policy Project at the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE). He has written extensively on the development of UK Trade Policy post Brexit, in the context of developments in EU and global trade policy on which he also researches and writes. L. Alan Winters is Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and former Director of the UKTPO.

One of the most heralded claims for Brexit was taking back control of UK international trade policy. Four years later, this is not widely seen as having been a success. Trade growth has been disappointing, the UK has become less open, exporting is still heavily concentrated in the Southeast of England, and there is little trust in Government pronouncements on trade. And yet there is almost no coherent discussion of trade policy and no evident strategy guiding future policy objectives or the signature of new trade agreements.

Part of the issue is that thinking about trade policy is trapped in the remnants of the Brexit debate and substantially seen in party political terms; it is consequently lacking any broadly accepted understanding. This is unsatisfactory and as part of the solution we propose to return the UK Board of Trade to its former status as a centre of excellence offering advice to the government and a source of impartial public information on international trade policy. Our paper is not the first to suggest that the Board of Trade be revived from its current somnolence, but it is the first to propose some details and a road map for that revival.

Our restructured Board of Trade would be a non-departmental public body – a well-established form for similar functions offering public service where there is a significant advantage of operational independence. It would be largely independent of government but nonetheless, work alongside government and all stakeholders to significantly elevate the UK’s trade policy debate and trade performance.

What would a restructured Board of Trade do?

The Board’s most prominent task would be to produce an annual report on UK trade performance and assess major new trade-related policies including trade agreements. This would be produced after extensive consultation with stakeholders and would be made public in an accessible form and debated in Parliament.

The Board would provide two impact evaluations of major prospective free trade agreements (FTAs), one at the stage of conception to see if it was worth pursuing and what the negotiating mandate should be (as the government currently does), and one close to completion of the negotiations, which would provide public information and sufficiently detailed analysis to allow Parliament to have an informed debate about whether to ratify the agreement. (Improved Parliamentary scrutiny of FTAs would be a second element of our improvement plan.) The Board would also conduct ex post evaluations of previous agreements in order to optimise them and learn lessons for the future.

Many modern trade problems concern regulation and trade, particularly in services. For example, there is a growing body of trade and climate change regulation, where there will be impacts both on trade and wider policy objectives. The Board would be required to consider major interfaces between trade and regulation, explaining them to the public and policymakers and helping with solutions.

Finally, we envisage a series of reports on specific trade and trade policy developments. These may include both detailed exercises to underpin future policy and simple explainers for the interested public.

Underpinning the Board’s work, there should be substantial and substantive engagement with Parliamentarians, stakeholders and the public. This would be partly aimed at improving policy and policymaking by encouraging a broad range of inputs, but also at building confidence that the UK had a satisfactory and inclusive approach to trade.

A model for a restructured Board of Trade

The challenge in designing a new Board of Trade is to create a balance between expertise/experience, independence from government, stability in the long-term policy vision and the fact that government, and to a lesser extent Parliament, must have a material role in the composition of a body with which they are intended to work closely. We suggest one model but recognise that others are possible.

Maintaining good relations between the Board and the government will be necessary for the former’s success. Hence, in our model, the relevant Secretary of State would continue to be termed the President of the Board of Trade and should appoint the members of a small politically balanced Board. These would have input to the Annual Report and formally receive it.

The main leadership of the Board’s work, however, would come from a Trade Council, with broad representation and expertise/experience in trade (not just exporting!). The Secretary of State would appoint the Council Chair in consultation with the relevant Parliamentary Committees and also a few members of a Trade Council. The majority of the Council would be nominated by the Chair and the whole Council approved by the small formal Board. The Chair would also appoint a Chief Executive Officer to lead the day-to-day work having consulted the Chairs of the relevant Parliamentary Committees.

The reconfigured Board of Trade should be established in legislation and have a guaranteed role in informing Parliament. It could, however, be created in shadow form virtually as soon as a government desired it, with formal statutory establishment following later.

By looking at similar UK institutions and the Swedish National Board of Trade, we estimate that the Board might require a staff of around 90 and an annual budget of about £10 million. At least some of these would come from the transfer of existing functions and staff from inside government. Lest this seems like a lot in our current straitened circumstances, recall that around one-third of UK consumption and investment comes from imports and around one-third of output is exported.

Getting trade right is important! Our proposal fills what is an obvious gap in current arrangements, with a view to building the broad consensus that is essential to a successful trade policy.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher May 22nd, 2024

Posted In: UK- EU

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() 13 December 2023

13 December 2023

James Harrison is Professor in the School of Law at the University of Warwick. Emily Lydgate is Professor in Environmental Law at the University of Sussex and Deputy Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory (UKTPO). Ioannis Papadakis is a researcher at the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and a Research Fellow in Economics. Sunayana Sasmal currently serves as a Research Fellow in International Trade Law at the UKTPO. Mattia di Ubaldo is Fellow of the UKTPO and Research Fellow in Economics of European Trade Policies. L. Alan Winters is Founding Director of the UKTPO, Co-Director of the CITP and Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex.

In answering this important question, different disciplinary approaches have emerged as have a range of different and sometimes contradictory findings. At the moment, scholars from the different disciplines are not talking to each other about the implications of this. The authors of this blog suggest it is vitally important that they begin to do so.

Trade agreements around the world increasingly include environmental and labour provisions. Their presence attests to policymakers’ recognition that trade agreements cannot simply focus on economic issues. They should also address environmental and social concerns. But the existence of these provisions on paper is not itself a cause for celebration. Such provisions are only meaningful if they have positive outcomes in reality – if they, for instance, lead to decreased carbon emissions or enhanced conditions for workers.

Different methodological approaches to researching this issue have come to different conclusions about their real-world impact. First, quantitative studies, largely undertaken by economists, have tended to identify significant and generalised positive impacts for at least some provisions.

On the environmental side, one early influential study found that EU FTAs with environmental provisions improve environmental conditions in countries with strong civil societies. It also concluded that US FTAs are effective during the negotiation period in improving the environmental policy environment of partner countries. Another, covering 680 PTAs with environmental provisions, found that environmental provisions can help reduce dirty exports and increase green exports from developing countries.

In relation to labour provisions, one study found that the likelihood of a state fully protecting workers’ rights rises by 10% once it has signed an FTA with the EU which contains labour provisions. Another study found that labour provisions had a positive impact on (particularly female) labour force participation rates (although not on other labour rights).

On the other hand, more recent work, carried out with more advanced statistical techniques and more granular data on both the content of FTAs and the environmental outcomes, tends to find only mixed evidence: some specific provisions on greenhouse gases appear to be effective, but results are not consistent across models. No significant effects are found for labour provisions. Some recent work has also focused on specific outcomes produced by environmental provisions. Thus, one study, focused on deforestation, found that environmental provisions are effective in limiting deforestation following the entry into force of FTAs, but only because FTAs without such provisions increase deforestation and the provisions offset this.

There is also some indirect evidence of the effects of FTAs. One study suggests a positive relationship between domestic environmental legislation (not environmental outcomes) and preferential trade agreements with environmental provisions, while another finds that FDI is deterred if FTA labour and environmental provisions have a higher degree of legalization. However, others suggest that such provisions might increase the costs of trade and production.

To sum up this first side of the literature, quantitative studies tend to suggest that some generalisable, although often limited, effects can be ascribed to labour and environmental provisions in FTAs. Across a wide range of different agreements, these studies suggest that some changes will happen as a result of the presence of some types of provisions – for instance that deforestation will be limited or domestic environmental legislation will be signed.

Legal scholars are often puzzled by these results. Environmental and labour provisions take multiple forms in different FTAs and are often not the kind of binding and enforceable provisions that are expected to produce significant results. In high-level summary, trade and sustainable development (TSD) chapters (as found in EU FTAs) and equivalent provisions in other FTAs often consist of ‘best endeavours’ clauses that commit parties to work towards high standards; cooperation on thematic issues, including through upholding agreements such as conventions of the International Labour Organization or the Paris Agreement; and obligations not to reduce levels of protection, often described as non-regression clauses.

Much debate has focused on whether these non-regression clauses should be tied to sanctions, as the US has done, and more recently the UK, Australia and New Zealand. In contrast, EU FTA commitments emphasize implementation through stakeholder dialogue of bespoke committees, such as a Civil Society Forum and Domestic Advisory Group. The EU has unveiled a plan for a limited increase in the use of sanctions in TSD chapter enforcement, and the USMCA has introduced new and innovative forms of labour rights enforcement.

Enforcement mechanisms remain an important focus for legal scholarship, as does the influence of FTA negotiations in changing domestic environmental and labour laws. However, focusing solely on treaty texts and the strength of the bodies that potentially enforce them, doesn’t provide a full account of the impacts of particular provisions.

Qualitative studies have been used by political scientists, geographers, business and socio-legal scholars to attempt to understand how obligations contained in treaty texts have translated into changes in labour and environmental outcomes. Such studies have generally involved case study methodologies and techniques such as in-depth interviews, focus groups and participant observation that allow deep exploration of the causal effects of certain sustainability provisions.

Most of the detailed studies have focused on EU trade and sustainable development (TSD) chapters and the labour standards provisions therein – although as environmental provisions are implemented and enforced in the same way, there are some learnings from these studies on the environmental side. Case studies on impacts in the EU’s FTAs with the CARIFORUM countries, Colombia, Korea, Moldova and Peru have found little or no evidence that the existence of TSD chapters led to improvements in labour standards governance, nor that there were significant prospects for longer-term change. Less robust studies of labour standards provisions in individual US agreements have led to similar conclusions. Positive impacts have been found to occur only in very limited scenarios when accompanied by specific actions by key actors (government officials, civil society actors, trade unions etc.), in relation to specific trade agreements where those issues became politically contentious, such as prior to the ratification of the EU-Vietnam FTA.

Overall, the findings of the studies presented here are very different. But their methodological strengths and weaknesses can also be contrasted. Quantitative studies are able to consider labour and environmental provisions across a wide range of agreements, thereby providing information about general tendencies. But these studies, particularly the earlier ones, are less compelling on the issue of causality. While sustainability provisions are posited as a likely cause of improvements in environmental and labour protection, there are generally weak attempts to substantiate causal links. The few studies that do make serious efforts to identify causal (and unbiased) links, tend to come up with many fewer positive effects. Most importantly, however, they all lack a convincing narrative about the mechanisms leading from FTA provisions to impacts on the ground.

Qualitative studies take causality seriously and can give detailed answers on the direct causal questions of how and why sustainability provisions have or do not have effects. On the other hand, they are weaker when it comes to generalisability; reliance on individual case studies leaves qualitative studies open to accusations that they have missed the ‘bigger picture’.

Scholars who have adopted these different approaches should come together to try to understand the rationale for these different findings and to promote better understanding of their respective research methods. Drafting this blog challenged some of our assumptions about how different disciplines tackle research questions, and facilitated our understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of our research approaches.

But this is not only an academic question. Understanding these methodological strengths and weaknesses has implications for policy making, as correct and full facts are essential to make good policy. For instance, there are policies with unintended consequences that can be identified by talking to people. When these are not considered, empirical analysis may lead to misleading policy prescriptions, even if the effects it estimates are precise, causal and generalisable.

Policymakers need to understand the effects of labour and environmental provisions if they are to take the right kinds of actions to promote better social and environmental outcomes through trade agreements. The authors of this blog all agree that there is a big difference between (1) telling policymakers they can achieve meaningful change through inserting environmental or labour provisions into trade agreements and (2) that to be effective, they must think very carefully about both the design of those provisions and how they will be taken up and utilised by key actors thereafter.

A broad account of how the disciplines can work together might go something like this: Economic studies identify FTAs where the correlation between environmental or labour provisions and positive outcomes appears to be high. Legal scholars bring a detailed understanding of the typology of FTA environmental and social provisions within these FTAs, using this to further refine economists’ findings about causal mechanisms. Political scientists, geographers, business, and socio-legal scholars interrogate how issues such as relationships, power asymmetries, access to information and access to resources shape the effectiveness of the environmental and social provisions in practice.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher December 13th, 2023

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

Tags: Environment, environmental law, EU, FTAs, labour standards, Trade agreements, trade policy

June 21 2023

Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Guillermo Larbalestier is Research Assistant in International Trade at the University of Sussex and Fellow of the UKTPO.

This is an extract from a paper first published on The Review Of European Law journal on may 5, 2023. To read it in its entirety, click here.

In the extract below we suggest that there are few trade benefits to be had. Is there something else that enhances economic viability? Is it as “regulatory sandboxes”? The present regulations require adherence to international environmental and financial standards. So what about R&D? There are some wind turbine, carbon capture and “Green Hydrogen” projects but not much linkage to Freeports. We don’t address the recent accusations of financial irregularities, yet clearly, property speculation is the other way to profit. (more…)

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 21st, 2023

Posted In: UK- EU