Differences in emphasis and interpretation

Flows from Great Britain to Northern Ireland

Flows from Northern Ireland to GB

Imports by Northern Ireland from third countries

Under the UK-EU ‘Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland’ which forms part of the Withdrawal Agreement between the UK and the EU, Northern Ireland remains in the UK’s customs territory while continuing to apply the EU’s customs legislation and some of the Single Market rules for goods. ‘The UK’s Approach to the Northern Ireland Protocol’ Command Paper, published on the 20th May 2020, presents the UK Government’s position on the implementation of the Protocol. In part, it is intended as a paper that sets out the Government’s vision for implementing the Protocol, but in so doing, is also a response to concerns made recently by the EU about the perceived lack of visible progress on preparations in the UK for introducing appropriate border procedures which need to be in place by 1 January 2021. The Command Paper attempts to set some boundaries (not quite red-lines) which the UK would like to establish.

The document raises three key sets of issues. First, it is clear that significant differences remain between the UK and the EU which need to be resolved, and these will no doubt spill over into the future relationship negotiations. These difficulties would need to be addressed before the end of the year, whether the future relationship talks are successful or not. Importantly, even if the UK and the EU manage to reach a deal, many of these issues will still be applicable. Second, how they are resolved will then have important implications for the people and the economy of Northern Ireland. Third, and an often-forgotten by-product of the Protocol, is the impact these changes will have on trade and relations with third countries for Northern Ireland.

With regard to the differences between the UK and the EU, some of these are a matter of emphasis and interpretation. Each party has a motive for presenting the agreement in a particular way, and in these cases, the differences are probably not substantive. The substantive differences arise in determining which goods will be subject to checks and on which flows, and how the checks will be carried out to the satisfaction of both the UK and the EU, and relatedly, what infrastructure and institutions are needed to ensure this takes place. Most of our discussion focusses on the ‘which’, as to a large degree this will then determine the ‘how’.

The uniqueness of the border in the Irish Sea results from the application in Northern Ireland of the Union customs legislation as well as the EU’s Single Market rules for goods (but not services). The UK Government is understandably keen to stress that Northern Ireland will remain an integral part of the UK’s territory, but in so doing, it significantly minimises the unprecedented and unique status of Northern Ireland under the Protocol. It downplays the fact that the border in the Irish Sea will be the EU’s external border. Hence, instead of stating that trade in goods in Northern Ireland will remain governed by Single Market rules, Paragraph 8 mentions that the Protocol “gives effect to certain aspects of EU law in Northern Ireland”. Paragraph 16 states that the Protocol “does not (…) create – nor does it include any provision for creating – any kind of international border in the Irish Sea between Great Britain and Northern Ireland”. This is to a large extent a question of semantics. While the border in the Irish Sea is not meant to divide the UK into Great Britain and Northern Ireland, it is de facto, an international customs border (the EU’s external border) running through the UK’s territory. A lot is also made in the Command Paper of the provisional basis of the solution (which is dependent on the ongoing consent of Northern Ireland’s political representatives), and this is at least implicitly used by the UK Government as justification for a softer and more flexible approach to the implementation of the Protocol.

The Protocol places the customs and regulatory border between the EU and the UK in the Irish Sea with the EU’s customs legislation applying to Northern Ireland. The Protocol specifies that EU tariffs would apply to goods entering Northern Ireland (“NI”) from Great Britain (“GB”) if they were at risk of entering the EU market. Specifically, all goods were to be considered “at risk”, and thus subject to EU tariffs, unless it was established that they would not be subject to commercial processing in Northern Ireland or they were otherwise exempt[1].

The Command Paper confirms that some tariffs will be due on goods moving from GB to NI, but here again, there are issues of interpretation. The Protocol specifies that tariffs will be levied on goods shipped from GB to NI unless it can be proven that the goods are not “at risk” of moving into the EU market. The Command Paper re-defines the original wording of goods “at risk” to goods where there is “a genuine and substantial risk”. In the Protocol, those goods used as intermediate inputs (commercial processing) were one of the types of goods that were considered “at risk”. The Command Paper downplays this issue. It does so by using agri-food processing as an example of goods involved in commercial processing, but in the example given the goods are sent back to GB – and so the document concludes they are not at risk. The alternative of agri-food processing goods which could then be sold on to the Republic of Ireland or elsewhere in the EU is not considered. This is clearly more than semantics and suggests that discussions in the Joint Committee will be fairly robust.

Table 1: Comparing text in the Protocol and the Command Paper:

| Issue | NI Protocol | Command Paper |

| Tariffs on goods entering NI | No customs duties shall be payable for a good brought into Northern Ireland from another part of the United Kingdom by direct transport, notwithstanding paragraph 3, unless that good is at risk of subsequently being moved into the Union, whether by itself or forming part of another good following processing (para 5.1) | It enables tariffs to be collected on goods at risk of entering the EU’s Single Market at ports of entry, rather than at the land border that is the legal boundary between the UK and EU’s customs territories (para 16). |

| Goods at risk | A good brought into Northern Ireland from outside the Union shall be considered to be at risk of subsequently being moved into the Union unless it is established that that good:

(a) will not be subject to commercial processing in Northern Ireland; and (b) fulfils the criteria established by the Joint Committee in accordance with the fourth subparagraph of this paragraph. (para 5.2) |

Trade going from the rest of the UK to Northern Ireland: we will not levy tariffs on goods remaining within the UK customs territory. Only those goods ultimately entering Ireland or the rest of the EU, or at clear and substantial risk of doing so, will face tariffs (para 17.2). |

| Determining goods at risk | Before the end of the transition period, the Joint Committee shall by decision establish the criteria for considering that a good brought into Northern Ireland from outside the Union is not at risk of subsequently being moved into the Union.

The Joint Committee shall take into consideration, inter alia: (a) the final destination and use of the good; (b) the nature and value of the good; (c) the nature of the movement; and (d) the incentive for undeclared onward-movement into the Union, in particular incentives resulting from the duties payable pursuant to paragraph 1. (para 5.2) |

There should be no tariffs on internal UK trade because, as the Protocol acknowledges, the UK is a single customs territory. Tariffs should only be charged if goods are destined for Ireland or the EU Single Market more broadly, or if there is a genuine and substantial risk of them ending up there.

If a supplier in Great Britain sends goods to a business for sale in Northern Ireland, then that is internal UK trade. Raw produce from Great Britain for agri-food processing in Northern Ireland which is then sent back to Great Britain is another good example of trade which is internal and has no impact on the EU market. A supermarket delivering to its stores in Northern Ireland poses no ‘risk’ to the EU market whatsoever, and no tariffs would be owed for such trade (para 25). |

| Waivers and reimbursements by the UK Government | Customs duties levied by the United Kingdom in accordance with paragraph 3 are not remitted to the Union. Subject to Article 10, the United Kingdom may in particular:

(a) reimburse duties levied pursuant to the provisions of Union law made applicable by paragraph 3 in respect of goods brought into Northern Ireland; (b) provide for circumstances in which a customs debt which has arisen is to be waived in respect of goods brought into Northern Ireland; (c) provide for circumstances in which customs duties are to be reimbursed in respect of goods that can be shown not to have entered the Union; and (d) compensate undertakings to offset the impact of the application of paragraph 3 (para 5.6). |

In any case, to ensure that trade flows freely, the Government will make full use of the provisions in the Protocol giving us the powers to waive and/or reimburse tariffs on goods moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland, even where they are classified as ‘at risk’ of entering the EU market (para 27). |

One of the questions the Joint Committee was tasked with was to agree on a mechanism to determine risk. More specifically, Article 5 Paragraphs 2 of the Protocol stated that the Joint Committee “shall by decision establish the criteria for considering that a good brought into Northern Ireland from outside the Union is not at risk of subsequently being moved into the Union”. It is important to clarify that such criteria do not currently exist. Such criteria are not part of customs procedures as normally the territory the goods enter is their final destination unless other customs procedures are triggered. In short, there has been no need for this to date, and the requirement to determine goods at risk will be challenging as the final destination of the goods will be unknown at the time of crossing the Irish Sea border.

In a previous UKTPO blog[2] three possibilities were suggested as to how the final destination and therefore risk could be identified:

The three methods differ in terms of the administrative burden placed on companies and the degree of visibility and certainty they provide for customs authorities. With all three methods, there would be some degree of non-compliance as no checks would be conducted on the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Source: Broad Economy Sales and Export Statistics, NISRA

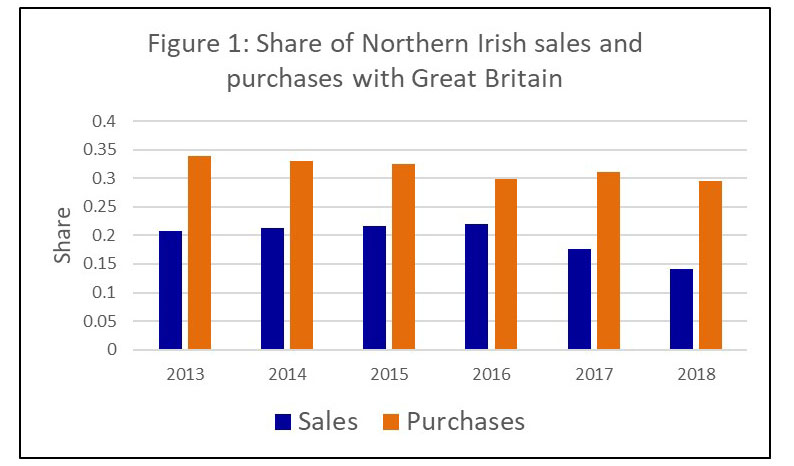

For Northern Ireland what matters is how much trade and economic activity could be affected. However, the lack of detailed data on sales and purchases between NI and GB, and the absence so far of a clear definition of goods ‘at risk’, makes it hard to quantify the actual amount of trade that could be affected. Nevertheless, the strengths of the links between NI and GB, can be seen in Figure 1, which gives the share of the total sales of firms in Northern Ireland going to Great Britain, and also the share of their total purchases coming from Great Britain. From the Figure, we see that GB is an important supplier to Northern Ireland accounting for close to 30% of purchases. With regard to those purchases, there has been little change over time, with only a modest decline since 2015. If we treat purchases from GB together with imports, then the share of GB in total NI imports declined from over 68% in 2013, to just over 60% in 2018.

Turning to sales, Great Britain is again important for Northern Ireland. It is interesting to note the large decline in the share of sales going to GB since 2016, from 22% of all sales to just over 14%. This is a substantial change, and there are two further aspects of this which are worth noting. First, shares do not tell us about whether, in value terms, trade with Great Britain has been rising or falling. It turns out that the decline in share is because of a decline in the value of trade – in nominal terms sales to GB were 40% lower in 2018 compared to 2016. Second, the data indicate that the reorientation of sales has primarily been to increase domestic sales which, over the same period, increase by 3% in value[3]. Of course, without a more formal examination, this cannot all be simply attributed to ‘Brexit’. Nevertheless, it seems likely that the prospective departure of the UK from the EU may have played an important role in these changes.

The amount of NI trade (purchases from the UK), and the specific goods which may be deemed ‘at risk’ will depend on the decisions of the Joint Committee. In turn, this will depend on whether or not the negotiations of a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with the EU are successful, and on the number of goods for which the UK tariff differs from the EU tariff.

The UK’s post-transition Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariffs, also announced in May 2020, and called the UK Global Tariff, involved the liberalisation of a substantial number of tariff lines. Earlier work by the UKTPO, based on the previously published ‘no-deal tariffs’, suggested that up to 82% of Northern Ireland’s imports of goods from outside of the EU may be subject to EU tariffs on their arrival in the region[4]. This is because 75% were intermediates, and therefore classed as at risk, and that 28% of the remaining goods were at risk on the grounds of tariff differentials. Hence 82% in total. As the UK Global Tariff proposal involves less liberalisation than the previously announced no-deal tariffs, the amount of Northern Ireland’s imports that would potentially be affected is likely to be lower but will remain substantial, if nothing else because of the high proportion of intermediates.

In the event of no-deal between the UK and the EU any differences in their respective MFN tariffs become important. All goods ‘originating’ in the UK, going to Northern Ireland and where there is a tariff differential might be considered ‘at risk’. At the level at which many tariffs are defined (typically what is called the 8-digit level), there are 9481 different products in the UK Global Tariff[5]. Under the UK Global Tariff, the UK tariff is always either equal to or less than the EU tariff. For just over 26% of these both the EU and the UK have zero tariffs (see Table 2) and these products are therefore not likely to be considered ‘at risk’ (at least on grounds of tariff differentials) whether or not there is a FTA agreed between the EU and the UK.

As shown in Table 2, there are, however, 4669 8-digit products, accounting for over 55% of the UK’s (8-digit) ad-valorem tariff lines, where the UK tariff is lower than the EU’s tariff. One possible interpretation of goods at risk would automatically include all these goods where the UK’s MFN tariff was less than the EU’s. It is possible, however, that the EU and the UK could agree on a slightly softer position, which, for example, considered only tariff differentials of more than 3 percentage points. Then, there would be 1012 products which fall into this category, accounting for 12% of the UK’s ad-valorem tariff lines (tariffs defined as a percentage of value of the good).

Alternatively, suppose there was a successfully negotiated UK-EU Free Trade Agreement with zero tariffs on all goods with the EU. Goods which originate in the UK could then enter the EU duty-free. Therefore, any such goods shipped from Great Britain to Northern Ireland should be able to enter the EU market duty-free, and therefore should not be ‘at risk’. However, this raises the question of determining the origin of goods. The EU will wish to ensure that where the UK has a lower MFN tariff, that goods are not shipped to the EU via the UK to take advantage of the UK’s lower tariff. In other words, goods will need to prove that they ‘originate’ in the UK in order to have tariff-free access into the EU market. Hence for any goods shipped directly from Great Britain to the EU, complying with rules of origin (i.e. the rules that determine the criteria for originating status) will be required. A certificate supporting that origin status would be required for goods shipped to Northern Ireland. In such case, there would be far less incentive for non-compliance, however, proof of origin would still need to be provided with each customs declaration. However, given the large number of goods for which the UK Global Tariff is lower than the EU’s, this raises the incentives for the trans-shipment of goods destined for the EU via the UK. Hence, even in the event of a free trade agreement between the EU and the UK, there will need to be controls on GB to NI trade, to check for originating status and to prevent trade deflection.

Table 2: Comparison between the EU and the UK tariffs

| All products | Intermediate products | |||

| Category | No. of products | Share of total | No. of products | Share of total |

| Products with EU MFN tariff > 0 | 6993 | 73.8% | 3441 | 36.3% |

| Products with EU MFN tariff > 0 (excl. non-AV) | 5941 | 70.5% | 3167 | 37.6% |

| Products with EU MFN tariff ≥ 3% (excl. non-AV) | 4435 | 52.6% | 2469 | 29.3% |

| Products with UK Global tariff ≥ 3% (excl. non-AV) | 3203 | 38.0% | 1493 | 17.7% |

| Products with tariff diff > 0 (excl. non-AV) | 4669 | 55.4% | 2734 | 32.4% |

| Products with tariff diff ≥ 3 ppt (excl. non-AV) | 1012 | 12.0% | 828 | 9.8% |

The Command Paper is also at pains to emphasise that no tariffs will be due on internal UK trade. This is consistent with Article 5, Paragraph 6 of the Protocol. On this, the Command Paper confirms that the Government “will make full use of the provisions in the Protocol giving us the powers to waive and/or reimburse tariffs on goods moving from Great Britain to Northern Ireland…” However, it then adds the clause “… even where they are classified as ‘at risk’ of entering the EU market”. This is a potential departure from the Protocol which allows for reimbursements but “in respect of goods that can be shown not to have entered the Union”. While the Protocol does appear to allow for the possibility of reimbursement for goods falling in the ‘at risk’ category, the Command Paper, does not explicitly recognise the condition which requires proof that the goods have not entered the EU. This may be simply differences of emphasis again or could prove to be a more substantial difference.

Importantly for businesses in Northern Ireland, there is no detail on how this would work in practice and what businesses would need to do to take advantage of such opportunities. Together with the process of determining goods “at risk” this is almost certainly going to lead to new paperwork and reporting requirements, as well as costs for companies in Northern Ireland and Great Britain.

Relatedly, the document confirms the need for both entry summary and import declarations for goods entering Northern Ireland. This is one of the first, if not the first time the UK Government has officially confirmed that both of these procedures will be required after a number of high-level officials and politicians stated otherwise. The document refers to these obligations as “limited additional processes” and confirms that the Government will take account of “all flexibilities and discretion” and “make full use of the concept of de-dramatization”. Yet, the requirements are bound to lead to additional cost, time and paperwork for businesses and represent a significant departure from how companies trade at the moment. For a majority of companies, this will also require the use of a customs broker or a logistic provider – as it is rare for companies to submit customs declarations themselves. This would lead to additional costs. It remains unclear what de-dramatization means.

The preceding discussion has largely focussed on the issue of tariffs. However, under the Protocol (Article 7), Northern Ireland will be part of the EU’s Single Market for goods. Hence, products placed on the market in Northern Ireland have to comply with the applicable EU regulations and conformity assessments.

The UK’s position is that the same bodies that undertake these functions today will continue to approve goods for the NI market. That means that the UK Government intends that some UK bodies will continue to verify goods based on EU regulation. According to the Command Paper, regulatory checks on industrial goods would take place through market surveillance and on business premises. This requires the EU to accept and recognise the relevant UK bodies to provide conformity assessment to their regulations. Indeed, this is consistent with the position taken by the Government in the draft text of the UK-EU FTA which the UK also published on 19 May 2020. The draft FTA assumes that the EU will accept the UK accreditation regime of testing and certification. However, this issue is clearly, if nothing else politically, related to the ‘level playing field’ stumbling blocks between the UK and the EU in the negotiations, and it is far from clear that the EU will accept the UK’s position on this. If it does not this will this will mean additional regulatory requirements for companies to comply with when goods are shipped from GB to NI even if it is accepted this still does not mean that inspections will not be needed for goods moving from GB to NI.

The Command Paper, also confirms that goods from NI approved and certified by EU authorities could freely enter GB. In practice, this means that as the UK diverges in terms of product regulations, two separate sets of rules would apply in the UK. It could, in turn, raise questions in terms of the UK’s prospective trade agreements with countries where the product regulation is an important point of contention in the negotiations.

On this, both the Protocol and the Command paper are in principle clear and allow for ‘unfettered’ access for Northern Ireland business to the rest of the UK. The Command Paper spells this out very clearly. According to the UK’s approach goods moving from Northern Ireland to Great Britain will not be subject to any formalities, documentary requirements or checks. Specifically, Paragraph 19 states that goods moving from NI to GB will be subject to:

While this is very clear, it also raises several tricky issues:

The Command Paper (Paragraph 17 (4)) states that this will be handled in accordance with the same principles as goods being shipped from Great Britain to Northern Ireland and from Northern Ireland to Great Britain, and that “where the UK has Free Trade Agreements with those countries, Northern Ireland businesses will benefit from preferential tariffs just as the rest of the UK will”. Important here is to remember, as discussed earlier, that in the UK Government’s Global Tariff there are a large number of products with a tariff which is lower than the EU’s Common External Tariff (CET).

So, for example, for goods imported by Northern Ireland from the United States, the EU CET will need to be applied to all such goods deemed ‘at risk’ of entering the EU (see discussion earlier which suggested that 75% of NI imports from outside the EU/GB are intermediate goods, and therefore by definition subject to commercial processing). If it can be shown that the goods did not enter the EU, then tariffs could be rebated. Once again this will depend on the final destination of the product. This is not something that is currently controlled or tracked for the majority of goods. For a small number of customs procedures where the outcome depends on the final destination of the product, for example, Inward Processing relief, additional controls with associated bureaucracy and costs are applied to monitor the movement of goods.

What about goods imported by Northern Ireland from countries that the EU has a Free Trade Agreement with (e.g. Canada), but the UK does not? If the good is destined for the EU market (either directly or as an intermediate input), then presumably the EU CET for that country should apply. If the goods are destined for the UK (either Northern Ireland or Great Britain) then the higher UK Global Tariff should apply. First, it is not at all clear which of the tariffs would be actually applied at the border, and how this would be managed. This means that the destination of the product will matter not only for goods from Great Britain moving to Northern Ireland but also for third-country goods arriving in Northern Ireland, and that appropriate procedures for determining risk and destination would need to be applied to these types of products as well.

Second, given that the UK Government has stated that there will be a complete absence of controls on goods flowing from Northern Ireland to Great Britain, there is clearly an incentive to apply the lower EU CET, even if the good is sold in either Northern Ireland or Great Britain. Once again this introduces the possibility of a ‘leaky’ border, where again concerns may be raised by the UK’s trading partners in the WTO.

From the preceding discussion, it is clear that some types of customs formalities and related checks will need to take place when goods cross the border from Great Britain to Northern Ireland, despite this being disputed on a number of occasions by representatives of the UK Government.[8] While some decisions are still to be made by the Joint Committee, the implementation of agreed border procedures in the Irish Sea has been left to the UK Government. The EU has recently expressed concern about the lack of apparent progress on implementation and has indicated that it would like greater evidence from the UK that it is taking its commitment in the Protocol seriously[9].

On this, the Command Paper (paragraph 32) states that there is “…no need to construct any new bespoke customs infrastructure in Northern Ireland (or in Great Britain ports facing Northern Ireland) in order to meet our obligations under the Protocol”. The exception to this, according to the Command Paper, is on the Sanitary and Phytosanitary checks for agri-foods. These will occur in existing locations, where ‘expanded infrastructure’ will be needed at Belfast Port, Belfast International Airport, Belfast City Airport and Warrenpoint Port. It is highly likely that the EU is also expecting the UK to install additional infrastructure at British ports.[10] It appears that with regard to the management of tariffs and customs by reference to electronic processes (Paragraph 29) the UK is planning to resort to technological solutions (reminiscent perhaps of those that were favoured by Prime Minister Boris Johnson as a solution on the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland). On the other hand, it is uncertain what the UK means by infrastructure. Does that cover physical infrastructure only? Or also additional staff required to monitor compliance with customs and Sanitary and Phytosanitary requirements. This is again likely to be a source of tension in the negotiations going forward.

Similarly, the rejection of the permanent EU presence in Northern Ireland and stressing the territorial integrity of the UK in the context of the UK’s sole control over the Irish Sea border (Paragraph 53 and 54), fails to take into account the EU’s concerns over their ability to oversee procedures on their external border.

Over the last few months, it has become evident that the interpretation of the Withdrawal Agreement’s Protocol on Ireland/Northern Ireland differs between the UK and the EU. The Command Paper published by the UK seems to cement these differences. The Command Paper does not fully address the challenges which come from the special situation around that border. It can be seen as an attempt at determining how the UK Government envisages the Protocol might be implemented and suggests some solutions, but these will need to be agreed with the EU, and that will not be straightforward. For companies, if they had any doubts until this point, it is now clear that full import procedures will be required for goods entering Northern Ireland. Given the uncertainty about any simplifications and waivers, companies should plan for this.

[1] See ‘Determining goods at risk’ (Jan 2020) : https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2020/01/14/determining-goods-at-risk/

[2] ‘Determining goods at risk’ (Jan 2020) : https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2020/01/14/determining-goods-at-risk/

[3] Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, Broad Economy Sales & Exports Statistics: https://www.nisra.gov.uk/publications/current-publication-broad-economy-sales-exports-statistics

[4]See: Expert Witness Evidence from Professor L Alan Winters CB: http://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/files/2019/12/full-final-draft.pdf

[5] Note that in the original UK Global Tariff schedule there are a total of 11,828 products as some products are defined at a more detailed level than the 8-digit level. However, for the purposes of this analysis the tariffs have been converted into 8-digit categories. Note that out of the 9481 8-digit tariff lines, 8429 are ad-valorem tariffs (expressed in simple percentages).

[6] ‘Truckers face paperwork mountain after Britain opts against fast-track security checks agreement with EU’: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2020/03/08/truckers-face-paperwork-mountain-britain-opts-against-fast-track/

[7] ‘Hard Brexit, soft Border. Some trade implications of the intra-Irish border options’ (December, 2017) https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2017/12/07/hard-brexit-soft-border/#more-1320

[8] https://www.dailymail.co.uk/video/news/video-2044970/Video-Boris-Johnson-tells-Northern-Irish-businesses-chuck-customs-form.html

[9] See ‘EU to press Britain on how it will honour Northern Ireland deal’ : https://www.ft.com/content/05dc978c-235e-494f-b343-7aada9db05a7

[10] https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/brexit-uk-eu-trade-deal-northern-ireland-border-checks-a9494116.html