The first women’s liberation movement (WLM) activist I interviewed was the proprietor of a small business. In 2009 I met Caroline Hutton who ran Women’s Revolutions Per Minute (WRPM) as a sole trader from the late 1970s-1990s.

Early in our interview I remember feeling a bit surprised when Hutton talked about the feminist music distribution company as a business.

Now, this may strike the reader as an admission of my startling ignorance about the ‘real world’. Yet it is worth stopping to consider why I could assume the WRPM was something other than a business.

Margaretta Jolly outlines in Sisterhood and After: An Oral History of the UK Women’s Liberation Movement: 1968-present, her forthcoming study of feminism and everyday life, that the prevailing common sense about the UK women’s liberation movement is that business, quite simply, had nothing to do with it.

Protests? Yes. Anti-capitalist sentiments? Certainly. But business? This seems almost totally at odds with the ethos of a revolutionary social movement that prided itself on resistance to economic, social and cultural injustices, doesn’t it?

It is, undoubtedly, anachronistic to view the enormous range of cultural, economic and social experiments generated within the WLM as ‘entrepreneurial’ or ‘enterprises’ or ‘businesses’ within the terms of today’s common sense. In 2018 these economic and social practices have been indelibly shaped through the interlocking forces of Thatcherism, neoliberalism, the New Right, the New Left, globalisation, financialisation and digitalisation.

Yet, as Jolly notes, we need only look askance at the archives of the WLM to find that ‘business elements’, as well as actual businesses, shaped a range of social, economic and cultural projects created within and around the movement. [1]

These ‘elements’ were incredibly diverse, but are all the outcome of women’s increased access to, and participation in, public life from the 1970s onwards.

The social worlds that emerged around women’s activisms in the 1970s and 1980s teem with examples of how women gained access to technical and economic knowledge which they used to reconfigure the organisation of society. These ‘enterprises’ ranged in size and purpose, from small group empowerment to international trade and exchange. Yet an ethos permeated throughout: a desire to change society and women’s place within it.

Some set up women-centred building companies like Barbara Jones’s Straw Works, or manual and technical labour training services, like the East Leeds Women’s Workshop which equipped working class, Black, Asian and disabled women with skills they could subsequently use in the labour market. Others, like Fakenham Enterprises, were one of many Worker Co-operatives established to resist redundancy amid the industrial crises that hit Britain in the early 1970s. With an all women workforce, the action at Fakenham sparked the imagination of WLM activists, who expressed their solidarity in awareness raising films made by the London Women’s Film Group or by ordering products made in the factory.

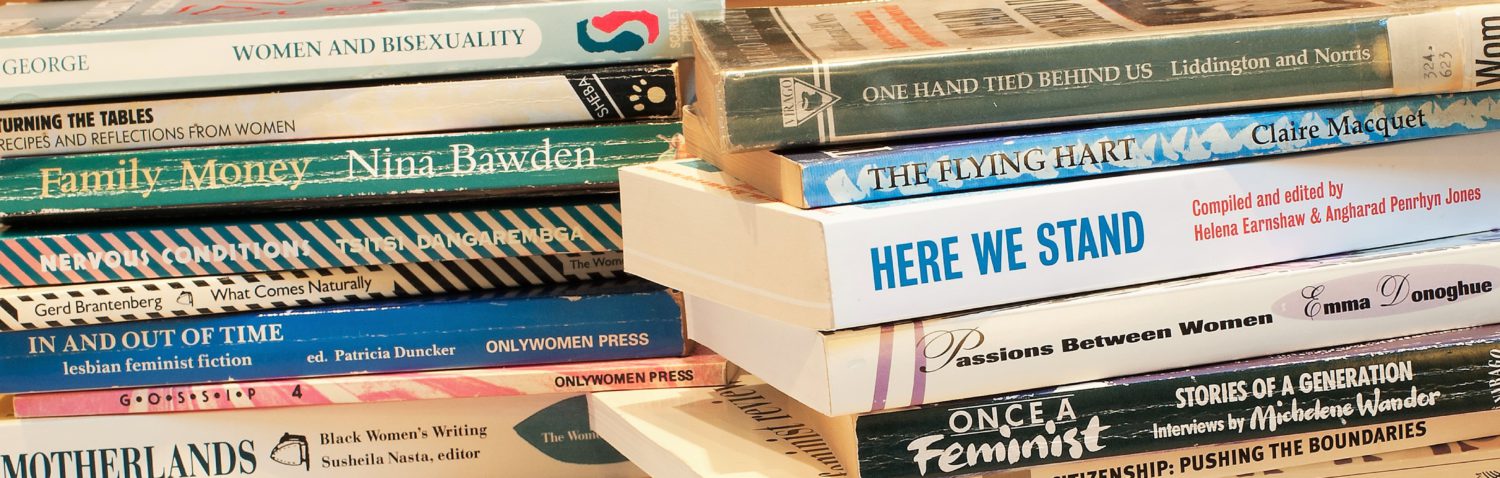

There was also the See Red Women’s Workshop, a collectively run silk-screen printing business that produced many iconic and eye-catching feminist posters. More modestly, members of the Fabulous Dirt Sisters took advantage of the Enterprise Allowance Scheme, introduced in 1981 by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government to support small businesses, to sustain their musical careers. And, of course, there were the numerous businesses engaged with producing women’s words for the marketplace – Sheba Feminist Press, Outwrite, Onlywomen Press – that form the central focus of our new research project.

Economic, cultural and social independence

The question of women’s economic, social and cultural independence was rigorously scrutinised within the WLM. These concerns were enshrined in the movement’s 5th demand – Legal and Financial Independence for All Women – and the ‘YBA Wife’ campaigns that accompanied it.

Why did such issues become the focus of feminist activism in the late 1960s and early 1970s? This was a historical moment shaped by a cluster of legal and technological changes that increased the possibility of women’s social independence. The contraceptive pill enabled women to decide when and if they were to have children – a genuine historical first – and changes to marriage and divorce laws made it easier for couples to separate if a relationship was unsatisfying at best, abusive at worst.

Nevertheless, these legal and social changes unfolded within a society that was rigidly structured by cultural attitudes embedded in the post-War welfare regime. At the core of the Beveridge Report – currently the subject of some reflection as we mark 75 years since its publication – were some undeniably conservative ideas. To summarise broadly: the ideal, economically productive household unit was to be a couple with a main ‘breadwinner’ (normally the man) who would have a partner that stays at home to raise children (normally the woman). She might work part-time but will not depend on her own wages. She did not need to, the logic followed, because everything was to be provided by her male partner.

In the late 1960s – and arguably still today – the labour market was structured by the assumption that women are economically dependent on men. While it became practically possible for women to make more exact reproductive choices and leave marriages and retain a degree of financial independence, substantial social mobility was difficult because the labour market offered little more than part-time or low-waged, full-time work.

In response to these constraints, activists in and around the women’s liberation movement not only fought for equal pay for work of equal value – important as this was. They also created numerous opportunities for women to assert and seize cultural, social, technological and, yes, economic independence.

By working together and establishing independent ventures, women bypassed some of the restrictions that arise when working for someone else – in this case ‘the Man’ in its totemic, patriarchal sense – whose structures offered nothing but the shoddy terms and conditions of de-skilled, low waged work, and female economic dependency.

The specific ways activists experimented with organisational practices to realise economic self-determination is one of the many questions we will explore in our new research project, The Business of Women’s Words. Ostensibly focused on the iconic cultural institutions of the WLM – Virago and Spare Rib – our enquiries will be situated within the structural and everyday economic realities activists and business women struggled against, and sought to transform.

We are likely to be challenged and surprised by what we encounter, much as I was when I spoke with Hutton, nearly a decade ago.

Notes:

[1] Margaretta Jolly (2019) Sisterhood and After: An Oral History of the UK Women’s Liberation Movement: 1968-present, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leave a Reply