Spare Rib – the iconic magazine of the UK Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1970s and 1980s, offered a small pleasure to readers looking for ‘love among the small ads’, despite its complex relationship to both advertising and romantic relationships. It started out with a minimal classified section and no personals (SR’s early classified pages ran to about half a page), but by the 1980s the classified section was a double-page spread, with ‘relationships’ the longest and – of course – the most eye-catching category.

The personals of 1970s and 1980s Britain enabled the public pursuit of new forms of relationality – same sex, casual, kink-led and non-monogamous arrangements, for instance. Spare Rib, with its mostly female, relatively radical readership, had an important role to play in this. Over time Spare Rib’s personals emerged as a service exclusively used by and for bisexual and lesbian women. Unlike City Limits and Time Out, which saw numerous ads from men self-defining as feminist, seeking feminist women, Spare Rib came to run personal adverts by women for women only. In this it offered a highly unique service as a dedicated national, public, print-based forum for lesbians and bisexual women seeking romance or other bonds with women – possibly the first and, at the time, the only such forum in Britain.

Although it ran sexually progressive personals with their own coded grammars of queer sexuality (‘Academic dyke, 25, feminist, non-scene, seeks similar’ – SR204, August 1989, p. 62), Spare Rib also reflected the maturation of the business of late 20th century lonely hearts. Many ads deployed what had become fairly universal cadences of the 1980s single, stating professional standing, income, and hobbies/tastes. Sometimes the two modes – queer sexuality on one hand and something approaching the spirit of Thatcherism on the other – were combined to potent effect, as, for instance with a ‘lesbian feminist 34’ of ‘Scotland/London’: ‘Dynamic attractive energetic, solvent professional, witty, adventurous lesbian feminist, 34, seeks her equal’ (SR 185 Dec 1987).

Spare Rib was not always as lesbian-oriented as it became in the 1980s; and its early foray into the personals even included the odd advert from a man – a fact which could easily become politicised. One such advert, from 1974, yielded a particularly strong response from a reader who felt that Spare Rib was no space to promote men’s sexual appetites, since these could be construed as sexually oppressive to women. Thus Marie Peyton, of Winchester, wrote in response to a man who had advertised for a younger woman that she felt ‘both extremely disgusted and depressed’ that SR had printed a personal from a man seeking a ‘sexual partner’ much younger than him. This had run counter to her expectations that Spare Rib offer women a ‘a new deal’ (SR 21, March 1974, p. 3). The reader went on to infer that if he’s retired ‘he will, at least, be 55 years, even assuming that he was allowed early retirement by his employer. The chances are 90-1 however that he is over 60. Why should a man of over 60 be encouraged to seek a women [sic] 20 to 25 years his junior in age, ie young enough to be his daughter?’ The reader noted that clinics were packed with depressed women over 40 who are considered ‘sexually finished’ and yet here was SR encouraging the circumstances leading to this state of affairs. She concluded by saying that she expected these kinds of ads to appear in magazines ‘like the National Advertiser and Time Out but I thought the purpose of your magazine was to clear people’s minds of the traditional prejudices against women, including middle-aged women, surely?’

Spare Rib actually offered a reply to this reader, showing that no detail or tension in its relationship to paid advertisements was too small for consideration. ‘We agree that this advertisement helps to perpetuate the idea that women are finished after the age of 40, but’, it added somewhat gnomically, ‘[we] feel that it’s no use replacing one rule with a similar ’. Tensions around age and sex in men’s personals were not revisited as the adverts settled into a predominantly same-sex (female) register – the few adverts from men that did appear avoided parading such traditional sexual sensibilities.

Dating Agencies

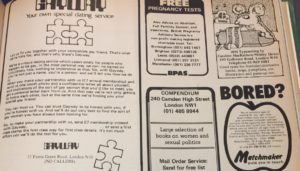

Gayway and Matchmaker ads in SR 39

Spare Rib’s encounter with the world of personal advertising also featured an additional component that was more pronounced in the magazine’s earlier years – display ads from dating services, preceding in some cases the arrival of personal ads. Thus the classified section of SR10 (May 1973) had no personals, but it did include an advert for a matchmaker called Contacts Unlimited, which described itself as a ‘Dating Service that always pays personal attention to selecting dates that really appreciate you and your scene.’ Other matchmakers also seemed to fit sexually progressive orientation of the magazine, such as Genda and Gayway. Genda, presumably a play on an open-ended notion of ‘gender’, possibly fused with ‘agenda’, said it was ‘for sound dating’. It was also part of the rising tide of technologically-elevated services – in this case voice recordings. ‘No hang-ups,’ the Genda ad read. ‘You don’t have to SPEAK. Just listen to the tape. Hear the voices of others like you, looking for friendship’. This technological innovation prefigured the 1980s and 1990s which witnessed the rise of video dating, and later the turn to digital platforms for dating services.

Others advertisers such as the well-established company Dateline, and to a lesser extent, the smaller-scale Matchmaker, were heteronormative or at best sexually neutral services. Despite their technologically advanced nimbleness in offering computerised matchmaking, these companies did not significantly innovate in their approach to fit the Spare Rib readership. Matchmaker placed small ads headlining the question, ‘Bored?’ Catering to a neo-liberal-style desire for instant gratification, the company promised to find readers ‘someone special right now’ as well as offering free horoscopes and free membership of a ‘travel and social club’ (e.g. SR 35, May 1975, inside cover). It also specified that it offered only ‘contacts of the opposite sex’. Dateline was owned by John Patterson, a libertarian Thatcherite with limited taste for the sexual politics and ‘excesses’ of ‘women’s lib’ (Strimpel 2017). The largest advert Dateline placed in Spare Rib, at half a page, ran with a banner that screamed, ‘WANTED: 1,000 Unmarried readers. Free computer test to find your perfect partner’ (SR 27, inside cover). Dateline, as I have reflected on elsewhere, was less interested in selling heteronormative sexuality than in selling its method. While it was clearly catering to singles keen on the traditional end of marriage (or at least who saw themselves as ‘unmarried’), it didn’t specify ‘opposite sex’ matching. Rather, Dateline was using the ‘great god computer’ to capitalise on new ‘modern’ discourses around psychology and personal growth: ‘using modern psychology, sociology and computer sciences, the computer will meticulously compare your personality profile with those of over 78,000 people, detail by detail’. (Strimpel 2017; SR 27, inside cover).

Others advertisers such as the well-established company Dateline, and to a lesser extent, the smaller-scale Matchmaker, were heteronormative or at best sexually neutral services. Despite their technologically advanced nimbleness in offering computerised matchmaking, these companies did not significantly innovate in their approach to fit the Spare Rib readership. Matchmaker placed small ads headlining the question, ‘Bored?’ Catering to a neo-liberal-style desire for instant gratification, the company promised to find readers ‘someone special right now’ as well as offering free horoscopes and free membership of a ‘travel and social club’ (e.g. SR 35, May 1975, inside cover). It also specified that it offered only ‘contacts of the opposite sex’. Dateline was owned by John Patterson, a libertarian Thatcherite with limited taste for the sexual politics and ‘excesses’ of ‘women’s lib’ (Strimpel 2017). The largest advert Dateline placed in Spare Rib, at half a page, ran with a banner that screamed, ‘WANTED: 1,000 Unmarried readers. Free computer test to find your perfect partner’ (SR 27, inside cover). Dateline, as I have reflected on elsewhere, was less interested in selling heteronormative sexuality than in selling its method. While it was clearly catering to singles keen on the traditional end of marriage (or at least who saw themselves as ‘unmarried’), it didn’t specify ‘opposite sex’ matching. Rather, Dateline was using the ‘great god computer’ to capitalise on new ‘modern’ discourses around psychology and personal growth: ‘using modern psychology, sociology and computer sciences, the computer will meticulously compare your personality profile with those of over 78,000 people, detail by detail’. (Strimpel 2017; SR 27, inside cover).

Spare Rib’s lack of appetite for such advertisers was made clear in page-settings such as that of SR27’s inside cover, when a no doubt costly half-page ad for Dateline was placed under none other than an ad for Lee Comer’s excoriation of the married state: her book Wedlocked Women.

It was Gayway dating service that had the strongest presence in Spare Rib from the start, paving the way for the distinctive character of the lesbian-centric personals that would feature in the 1980s. The personals brought together two disparate but interconnected themes in the business and content of Spare Rib: first, the commercial imperative to make money as ethically as possible, and second, the handling and – with possible revenue in mind – the mediating of romantic relationships. Romantic relationships and the numerous oppressions encoded within them were at the core of the women’s movement from the start, mostly in relation to men. By the time Spare Rib entered its middle phase in the 1980s, the frame had shifted, and so had the readership, towards a sexual culture that omitted men altogether.

Further reading

Harry Cocks (2004), ‘Peril in the Personals: The Dangers and Pleasures of Classified Advertising in Early Twentieth-Century Britain’, Media History, 10 (1), pp. 3-16: 1.

Harry Cocks, Classified: The Secret History of the Personal Column (London: Random House, 2009)

John Cockburn, Lonely Hearts: Love Among the Small Ads (London: Guild, 1988)

Zoe Strimpel (2017), ‘Computer dating in the 1970s: Dateline and the making of the modern British single’, Contemporary British History (published online).

Zoe Strimpel (2017), ’In Solitary Pursuit: Singles, Sex War and the Search For Love, 1977-1983′, Cultural and Social History (online).

Leave a Reply